The Idea: An overview of Michael Porter’s, Peter Drucker’s, and Chris Christensen’s approaches to innovation research. Research is probably the most undervalued, and poorly done, process in Western business. It’s not rocket science, but doing it well takes practice, a disciplined process, and strong creative, analytical and communication skills. Clay Christensen’s new book Seeing What’s Next is essentially a book about doing good research, directed at accurately predicting the future of your business, or of an entire industry, and the market forces that affect it. Whereas most predictions of the future done by analysts and accountants are essentially projections, and assume little or nothing will change except perhaps the volume and margin of sales, any really useful, strategic prediction must be a forecast, which identifies what will, or might, significantly change, disrupt the market and the status quo, and how your company can react to these anticipated changes. The forecast is the net result of these anticipated external market and non-market changes and your company’s planned response to them. The key to being able to competently anticipate such changes is knowing where to look and knowing what to look for. Michael Porter, in his book Competitive Strategy, identifies ‘five forces’ that provide one approach to doing so:

The last two of these five forces are the source of what Christensen in his earlier books called disruptive innovations — the ones that are often not foreseen when your focus is intently on customers, suppliers and competitors. So one way to predict the future for your company would be to do thorough research in each of these five areas, see what changes are occurring or what changes your company could precipitate, and how those changes and your company’s responses to them would ‘play out’ in the marketplace. It is not uncommon for research of this nature to use scenario planning techniques — to write several different ‘stories’ of how these changes might play out, and allow management and experts in the industry to assign probabilities to each before deciding what actions to take. I have already written about Drucker’s approach, in his book Innovation and Entrepreneurship, to knowing where to look and what to look for. For completeness, my synopsis charts of his innovation process are reproduced in the charts below. His ‘where to look’ is the seven innovation sources illustrated in Fig.2 below. His approach to analyzing these potential ‘change producers’ is described in Fig.3 below. His approach to identifying what changes may be coming is similar to Porter’s — look for the sources, do your research, and then analyze the implications critically — but he slices the ‘universe of change possibilities’ differently: Customers:

Competitors:

Strategies:

Just as a reminder, here from my earlier article are Christensen’s definitions of sustaining innovations and disruptive innovations:

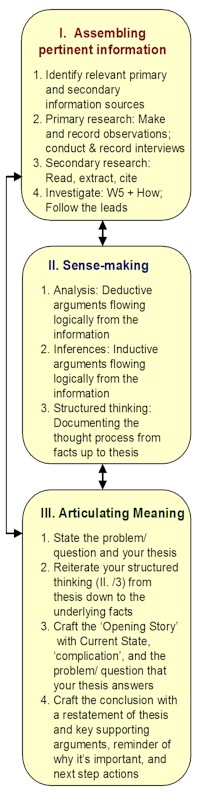

I like all three models — Porter’s, Drucker’s, and Christensen’s — and if I were to be assigned to do some innovation research today, I would use a combination of all three approaches, looking at the markets, and potential markets, and the forces that drive them, from all three perspectives. That way you can actually get a ‘3-D’ forecast of the future of your, or your client’s, business or industry, or the entire economy. I would also integrate into the research process Imperato and Harari’s Thinking the Customer Ahead approach, a type of primary research (i.e. face-to-face, as contrasted with secondary research, which is looking at written documents in the public domain) that entails helping the customer to imagine where their business is headed, and then working backwards to assess the implications of that on where your client’s business is headed. I would use the Pyramid Principle methodology to document the research and perform the analysis. And I would probably structure the results as scenarios or future-state stories, embedding the results of the identified strategic innovation and differentiation responses I would recommend the client undertake. If you want to practice applying these theories and doing your own research, analysis and “what’s next” forecasting, here are three intriguing exercises:

|

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

I’m going to take a shot at exercise 1. It’s a given that TiVo is not yet profitable, though with today’s announcement of the deal with Comcast that may change. I’m going to argue that TiVo is far from a death knell, despite the press it’s been getting lately.1. Are the “competitive technologies” really competitive? I’d argue no, except for the most basic functions. The ability of cable companies and satellite companies to compete with TiVo depends on several factors. The most relevent one at this time is the ownership of patents. The infringement lawsuit against Dish Network will have a lot to do with how the competitive landscape shapes up, but I’d bet on Dish losing, and TiVo ending up in a much stronger position.The deal with Comcast really says that Comcast has decided they can’t compete on technology at this point – only on price. Hence, they’ll offer the TiVo platform as a higher-end product.The second factor is application software. TiVo is generally considered to have the best GUI of the PVR’s and is certainly far ahead of either Motorola or Microsoft on offering functionality. TiVo’s Home Media Engine is attracting developers who are actually doing convergence applications – though it’s been available for less than three months, we’ve already seen proof of concept apps for Flickr streams, Ebay, Itunes, and email. Given that TiVo owns Strangeberry, the odd folks who had a LOT to do with developing Java, we can expect to see more convergence apps emerging in the next year or so – several years ahead of Microsoft’s timetable.I expect to see an RSS reader for TiVo in the very near future – and if it’s done right, enclosures or Media RSS will allow for IPTV applications and subscriptions in the same way that content can be subscribed to using the Season Pass or Wishlist options. Personally, I suspect that TiVo will form a natural platform for narrowcast video and vlogging – and I expect that market to grow enormously.In short, I’d argue that TiVo doesn’t need to reinvent itself, and that it’s not on the road to doom at all.

Hey Greg: That’s an excellent analysis. It would be interesting to see whether it would change if you studied all the players, current and potential in this space, and if you did some primary research with non-customers of TiVo to find out why they aren’t. I’d hypothesize for example that perhaps they are caught in the same bind as quality television producers — that the discriminating segment has already substantially abandoned the medium and watch so irregularly that TiVo does not provide enough value. Meanwhile, the undiscriminating segment, faced with hundreds of choices, can basically find something to watch anytime, and if they care enough about a program they’ll buy the whole series as a DVD set. So not only is the technology evolving quickly and in sometimes unexpected directions, so is the audience, the customer. That’s just a hypothesis — I’d need to do some real research to test it ;-)

Good questions, Dave. That would be a fairly long paper, but my conclusion wouldn’t change much. TiVo is a software company that makes hardware. So to look at all the potential players we have to look at the content sources (Dish, Comcast, et al); the CE manufacturers like Phillips; and the software/content/hardware/pipeline verticals like AOL/TimeWarner, Sony, NewsCorp, Microsoft, and so on. Convergence, in this case, seems to mean that a whole lot of folks can play in this sandbox. TiVo is currently pipleline independent, and an discussion of the competitive landscape would ultimately need to deal with that as a strategy.———————————-I’m convinced that for most non-users the primary factor is ignorance, followed by cost. If you look at the DVR market overall, it’s clear that the technology is just on the curve from early adopter to early majority. TiVo’s subscriber base grew somewhere around 20% in their last quarter – that curve is accelerating fast.——————————Your hypothesis of the “quality television” bind and the discriminating viewer is interesting, but misses two crucial points. TiVo solves both of those problems for the medium due to timeshifting and the “long tail”. A great many discriminating viewers own TiVos precisely because you can timeshift the things you ARE interested in. And if the discriminating viewers interested in your niche are a desirable target demographic, the long tail effect allows quality producers to target that niche effectively.————————————–So you’re right, the customer IS evolving in interesting and unexpected directions :)

Do you blog? There is currently a research survey out that seeks to know “why bloggers blog.” The study is being performed by a graduate student at Appalachian State University in North Carolina. The survey takes less than 5 minutes to complete. Thanks for your time. Click Here to take the survey

Been thinking about these examples. Whatever TiVo is as a manufacturer, it forgets the most important component: the customer. It has a lousy rep for poor customer relations, in spite of the fact it’s got one of the most fanatic “fan bases”. If they spent more time actively listening to their fans/customers instead of treating them like a nuisance, they’d probably lock up the niche for quite a while (until a disruptive technology came along and listened to TiVo’s fans/customers).Can’t help on the small car intro, but I think GM has an opportunity to improve its domestic market. One of the challenges GM faces is a glut of lease vehicles reentering the market in 2005, along with higher oil prices. If GM could find a way QUICKLY to retrofit the lease vehicles for improved efficiency and move them to China to sell for 3K, maybe it could take care of two problems at the same time. But that’s assuming the Chinese would even consider this…maybe if GM partnered with a Chinese company on rapid development of a hybrid-retrofit of these lease vehicles…?Sony has to develop “cool” — what’s “cool”? how does one compete with the cachet that is iPod? a response won’t be just a “me too” product; it would have to blow the socks off iPod, do everything that iPod does well and MORE. I wonder if a bootable device with PDA, video and phone capability combined with the ease of use of iPod’s functionality isn’t the answer, but it would have to have an awesome branding promotion to counter the cool that is iPod. (In some respects, if something matched TiVo’s capability and ease of use but was “cooler”, TiVo would bomb. Would customer dialogue be enough to make a competitor “cool”?)

Some ramblings from the Ideafarm…Having just bought an iPod shuffle, I’m loving the ability to listen to podcasts when I’m doing other stuff that doesn’t require my full sensory attention (like driving-joking ;) But it’s a relative schlep to get the content onto my iPod. I think the cellcos could become a major player (not sure about threat) in this space by combining UMTS/3G broadband connectivity, devices that play mp3/AAC, as well as a customer and billing relationship (SIM card). I’m very aware that consumers are calling for LESS stuff on their phones, but sometimes combinations make sense. Sony is struggling with NIH syndrome (read the recent New Yorker article) that has resulted in some very closed-loop innovations – memory sticks, Betamax, music players that only play their format. What makes the iPod so cool is the “insanely great” design and insight that goes into the product. That in turn creates the buzz factor of cool. In the same way, a product/service offering that just makes so much sense will be the next big thing. Hmmm…Apple + Motorola?McLuhan’s rear-view innovation commentary are also relevant to this discussion, something that Mark Federman at UT is far more competent at discussing than me, but saying the the forward trajectory of an industry is based on the past is flawed. Who would’ve thought that RSS feeds, Time-shifting, and the Long Tail would be keystone technologies and social drivers for the consumption of media.Bottom line, it’s the firms that have continuous, cluetain-esque, conversations with their customers, as well as the ability to make sense of all those insights, that are in the best position to “invent the future”, borrowing from Alan Kay.David – thank you for a most wonderful resource of innovation thinking and practice. Your work here is really appreciated.

Different types of Business Models of Michael porter you can find here also.