Continuing from Friday’s post, here are some additional highlights of Dave Snowden’s recent breakfast presentation on narrative, cultural anthropology, social networks, complexity in business, and all that stuff, with substantial embellishments from me, some of which are based on conversations with Dave and with other attendees: Continuing from Friday’s post, here are some additional highlights of Dave Snowden’s recent breakfast presentation on narrative, cultural anthropology, social networks, complexity in business, and all that stuff, with substantial embellishments from me, some of which are based on conversations with Dave and with other attendees:

- Established business wisdom suggests that if you tell people what to do, how and why to do it, they will. But cultural anthropology suggests that while they often want to be told this (to have knowledge of expectations), what they actually do is different. Most people do what they think works best. If what they’re told doesn’t ‘make sense’ to them, based on what they know, believe, perceive and experience, they’ll do something else. In fact if you tell them anything that doesn’t ‘make sense’ to them, it’s likely they won’t even hear it, it will be filtered out by their frames of perception and understanding. Our long-term memory has a capacity of about 40,000 patterns (models, archetypes, plans, idealizations and other representations of reality), and when we see, hear or otherwise pay attention to something we only perceive and internalize the 5-10% that resonates and is consistent with those patterns, that understanding of reality. There is evidence that until someone creates a mental pattern for a phenomenon, they are unable to ‘see’ it at all. And once a pattern has been set in the brain, it becomes very difficult to dislodge. This perhaps explains my observation that people tend to make up their mind on a new issue quickly but change their mind slowly. It could also explain first-mover advantage.

- We create those patterns from personal experience — direct (first hand) and learned (second hand), though the former is much more powerful. Philosopher Andy Clark has written that our minds are extremely plastic and malleable, and that the way in which our brain processes a story about or a memory of a particular phenomenon is indistinguishable from how it processes the original first-hand perception of that phenomenon. For that reason, context-rich stories are the most powerful means to convey knowledge, and the format that allows knowledge to be retained longest.

- Furthermore, since learning to avoid failure is a selected-for Darwinian survival mechanism, stories about failure are internalized more easily than success stories. The focus on positive stories diminishes the effectiveness of techniques like appreciative inquiry and ‘best practice’ harvesting.

- Differences between cultures (such as the differences between US and Canadian cultures depicted above, explained further in my earlier article) are principally the result of differences in entrained patterns in the brain, created by different stories. As Thomas King asserted, stories are all we are. If you want to understand a people, or an individual, or an organization, study its stories. You can no sooner change a culture than you can change the patterns in the brains of that culture’s adherents. That’s why brainwashing is so difficult, but in two generations you can achieve astonishing cultural change, as each new generation’s entrained patterns differ, from childhood, dramatically from their parents’.

- So rather than trying to change culture, you should try to understand the culture by collecting lots of anecdotes about it (cultural anthropology), and then find the patterns in those anecdotes to ‘make sense’ of that culture and people’s behaviours, and adapt your processes and tools accordingly. Things happen the way they do for a reason. If you fail to understand that reason, your attempts to bring about change will be foiled as people find ways to ‘work around’ the new rules and processes and tools that don’t ‘make sense’. If you do understand that reason, you can instead remove the obstacles and barriers that required the ‘workarounds’ in the first place, or put in place incentives (attractors) that are consistent with the culture and which will ‘make sense’ to those you offer the incentives to (so they’ll take you up on them).

- Post-merger integration is a perfect example of this. Two different organizational cultures are thrown together, and attempts are made to pick the ‘best practices’ from each. But it doesn’t work. Neither ‘side’ appreciates the other’s practices because their entrained patterns are different, the proposed new way simply “isn’t the way we do things”, so it doesn’t ‘make sense’ and it is not accepted. So usually the acquiree’s culture, behaviours and practices yield to the acquiror’s, and the key people from the acquiree leave (taking their knowledge and, often, better ways of operating, with them). This is one of the key reasons mergers destroy, rather than creating, value 85% of the time. Yet today’s paper is filled with more mega-merger announcements. Don’t they ever learn, or are acquirors so cynical that they’re satisfied with removing one more competitor so they can distort the free market and jack up margins?

- Two keys to effective cultural anthropology in organizations: (1) Study the informal networks, not the ones shown on the organization chart, and (2) Realize that managers are deliberately insulated from seeing the inefficiencies in their bureaucracies (because it’s in nobody’s interest to tell them the truth about them).

- In management selection and in collaborative activities, there is a dangerous tendency to select people like yourself. As a result you get groupthink, lack of innovation, and sycophants. Successful organizations select teams that are compatible but diverse.

- Social Network Analysis is now evolving from understanding relationships between individuals, to understanding relationships between identities. We have different identities in different communities, and relate to the same people differently in those different contexts.

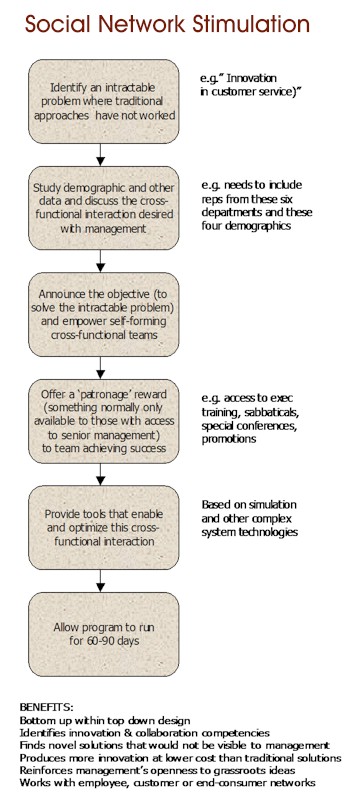

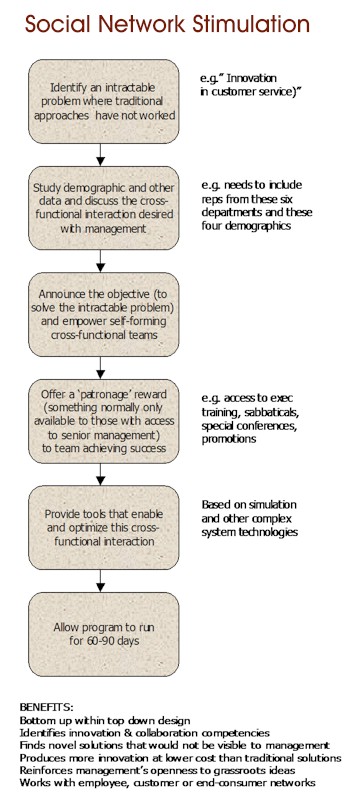

- The Grameen Bank has pioneered a new business approach called Social Network Stimulation (SNS). This entails (a) abandoning business models of causation (e.g. root cause analysis) in favour of models of correlation (studying the system/market as a complex one), (b) using a rule-based system to allow self-organized, self-assembled groups of people who already trust each other to form enterprises, and (c) focusing initially on low-volume, low-value markets (shades of Christensen’s disruptive innovations) and then working upwards from there. The process is diagrammed above.

|

Continuing from Friday’s post, here are some additional highlights of Dave Snowden’s recent breakfast presentation on narrative, cultural anthropology, social networks, complexity in business, and all that stuff, with substantial embellishments from me, some of which are based on conversations with Dave and with other attendees:

Continuing from Friday’s post, here are some additional highlights of Dave Snowden’s recent breakfast presentation on narrative, cultural anthropology, social networks, complexity in business, and all that stuff, with substantial embellishments from me, some of which are based on conversations with Dave and with other attendees: