In yesterday’s post, I proposed a methodology for customer-driven innovation that draws on the work of three groups (a) Christensen’s and Carr’s work on the four types of innovation, (b) Doblin Group’s ten ways to innovate, and (c) Chan and Mauborgne’s Blue Ocean Strategy Canvases. Today I’m going to test it out on a company that I know well, that went through a revolutionary innovation a generation ago. It’s a family-owned private company, and I’m not at liberty to divulge its identity, but if you want to know who it is e-mail me and I’ll whisper in your ear. I’ll call the company StandPat Printing. In yesterday’s post, I proposed a methodology for customer-driven innovation that draws on the work of three groups (a) Christensen’s and Carr’s work on the four types of innovation, (b) Doblin Group’s ten ways to innovate, and (c) Chan and Mauborgne’s Blue Ocean Strategy Canvases. Today I’m going to test it out on a company that I know well, that went through a revolutionary innovation a generation ago. It’s a family-owned private company, and I’m not at liberty to divulge its identity, but if you want to know who it is e-mail me and I’ll whisper in your ear. I’ll call the company StandPat Printing.

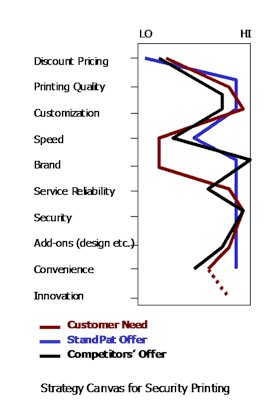

Twenty years ago, StandPat faced a crisis, one that had plagued it for most of the three generations since it had been founded. The commercial printing business was cutthroat. There were too many players, and now many new immigrants had come into the country and were using newer, cheaper technology to provide a product almost as good as StandPat’s for much less. The company had not significantly changed in size or nature in decades, and they were under enormous pressure to lower prices again. The company president decided this was a recipe for running the company into the ground, and that something drastic needed to be done. He did an analysis of StandPat’s and competitors’ offerings that would have looked something like the Strategy Canvas shown above. Not surprisingly, he discovered that StandPat’s offerings were misaligned with what the market wanted — fast and cheap. There were some repeat, blue-chip customers that demanded quality, customization and reliable, knowledgeable service, but even they were frequently tempted away by much lower prices of discounters. Worse, many large organizations were doing more and more of their work in-house (small printing presses were a disruptive innovation to established commercial printers), so even the blue-chip customers were giving StandPat only their most demanding jobs. And three well-established printers with strategy profiles just like StandPat’s were fighting furiously over this declining volume of premium work. The president looked at ways to innovate, and ways to compete more effectively for the low-end work. He tried to identify customer needs and wants that weren’t on the canvas at all — a myriad of ‘what if’ options were presented to customers, including low-end customers and non-customers. A number of ‘wants’ were suggested, but they were far beyond the technology of the day. So finally he decided he needed to look for entirely new markets for the attributes that StandPat offered. He kept bumping up again affordability and technology issues — the people who wanted high quality, convenience, and excellent service could not afford it. There was only one attribute that StandPat offered that seemed to have a market that could pay for it — security. In security printing (the printing of banknotes, stock and bond certificates, and postage stamps) there were few competitors and those with the capability to provide it were demanding and getting top dollar from customers with the wherewithal to pay it. The problem was, the few existing security printers already had close relationships with the potential customers in this business, and their offerings and strategy were quite similar to those of StandPat. What would it take to get these customers away from their current suppliers? For the next few years, it was touch-and-go for StandPat. Business was slow and difficult to bring in. StandPat focused on convenience, customization and service reliability, where they had a small competitive advantage. So they got work close to where their offices were (and they built some new ones close to where potential customers were). They did unusual jobs and small-run pilot project printing — too much set-up time and not enough volume for competitors. And they jumped through hoops to outservice their competitors. But all that was not enough. They needed to reinvent themselves further. It was when they started doing some scratch-and-win prize games for a gas station chain and a restaurant chain that they realized how they could really differentiate themselves. Existing security printers printed what they were told, how they were told. But what lottery foundations and corporations were looking for was imagination, innovation. These customers needed exactly what the mints and post offices and securities dealers needed, but they also needed some creative spark — and most of these customers did not have this creative spark in-house (and when they did have ideas for scratch-and-win games, the ideas were impractical). StandPat was helped by the fact that hackers had taken great pleasure in figuring out how to ‘read’ what was under the scratch-off coating without scratching it, using infrared or ultraviolet light or a variety of other ingenious techniques. There was a media frenzy over some of these, and several scratch-off lottery ticket and game competitors went out of business as a result. StandPat had done their homework and their tickets defied all the hackers’ challengers, and they had developed and patented a whole series of additional security measures as an extra precaution. Customers were delighted to know their reputation wouldn’t be tarnished by a ‘game that could be gamed’ and orders flowed in. The games came in many varieties and changed often, so that many security printers were unable to adapt fast enough or price new games competitively. StandPat revamped their security processes so they could produce a new game with very short turnaround, and they hired a creative team who knew the intricacies of security printing to design new types of ticket and game options for the lottery corporations and corporate marketing groups. Since then, the company has grown fifty-fold, does business with and in dozens of countries, and is vendor of choice because of their new and innovative offerings, their fast turn-around with new concepts, and their reliability and rock-steady security. So first they innovated their customers — who they sold to — and then they innovated their products. StandPat effectively went through the six-step customer-driven innovation methodology I outlined yesterday:

I remain convinced that steps 2 and 5 are the hardest. StandPat succeeded at them because they were intensely customer-focused but also imaginative enough to consider completely different customer segments from those they had traditionally served, and because they had the innovation skills, agility and courage to create and enter a new market space consistent with their culture and competencies, and do so in a systematic and methodical way until they had established themselves as market leaders. No easy accomplishment. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

The profile for this work, for this customer segment, looked more like the one at right. It was much more closely aligned with the competencies and strategy of StandPat, and although it would require a major investment in new equipment and a lot of retraining of staff in security measures.

The profile for this work, for this customer segment, looked more like the one at right. It was much more closely aligned with the competencies and strategy of StandPat, and although it would require a major investment in new equipment and a lot of retraining of staff in security measures.

Thanks Davethis artcile opened some doorways in my head to what can be done. the canvas concept is one i’ll review and utilise in my own business model and that of my clientsthanks