Place, the place we call home, the place we belong to, defines us. When we have lost our sense of place, we have lost our soul. Last Christmas I wrote a piece about homelessness, and suggested that the homeless and the addicted are a perfect metaphor for all of us living in modern civilization. I wrote: Civilization is our Pusher. It’s The Man who keeps us hooked on consumption and debt, The Man who holds the key to our prison and gives us our illusory rush of elation when we buy and use His addictive product. The Man who seduces us back even when we have decided that life in His prison is insane, self-abusive, worse than death. The monkey is our addiction, without which we cannot live. And we wander the streets of civilization’s artificial world in a daze, never really home, wondering what is missing, why we feel so lost. Civilization is our ghetto, a whole world of six billion homeless people, setting fires on every corner for warmth, ganging up and stealing everything we can get our hands on to pawn for our fixes, breeding babies already drug-addicted at birth.

So the next time you see a homeless person, or an addict, don’t be frightened, angry, or filled with pathos. You are looking in the mirror. It is we who are homeless, and addicted. What will it take before we break the habit, walk away from The Man, and find our way home? On another occasion I wrote: Know your place. We are all part of a web, a mosaic, and we all travel, but ultimately we have our own place, our ‘home’. If you’re not totally connected with everything and every creature that is part of your place, then it isn’t your place. If you don’t have a place, then you don’t yet really exist. A house is not a place, though if it’s open it can be part of one. A mind is not a place.

The wonderful books of biologist Bernd Heinrich are about birds and animals, but most of all they are about the places that the creatures he studies call home, and about the importance of those places. In his latest book The Geese of Beaver Bog he talks about another biologist, David Ehrenfeld, who writes about animals and the importance of place to them. I’ve ordered Ehrenfeld’s 1994 book Beginning Again, but I’ve already read the amazing first chapter from Amazon’s ‘search inside’ page for the book. The chapter is called ‘Places’ and here is an extract that shook me to the core of my being: Because the turtles [I was studying in Costa Rica] come out to nest after dark, much of my work was done at night. There was a great deal of waiting between turtles, plenty of time to sit on a driftwood log and think. In the first years of my research I was often the only one on the beach for miles. After ten or twenty minutes of sitting without using my flashlight, my eyes adapted to the dark and I could make out forms against the brown-black sand: the beach plum and coconut palm silhouettes in back, the flicker of the surf in front, sometimes even the shadowy outline of a trailing railroad vine or the scurry of a ghost crab at my feet. The air was heavy and damp with a distinctive primal smell that I can remember but not describe. The rhythmic roar of the surf a few feet away never ceased — my favourite sound. I hear it as I write in my landlocked office in New Jersey. And then, with ponderous, dramatic slowness, a giant turtle would emerge from the sea.

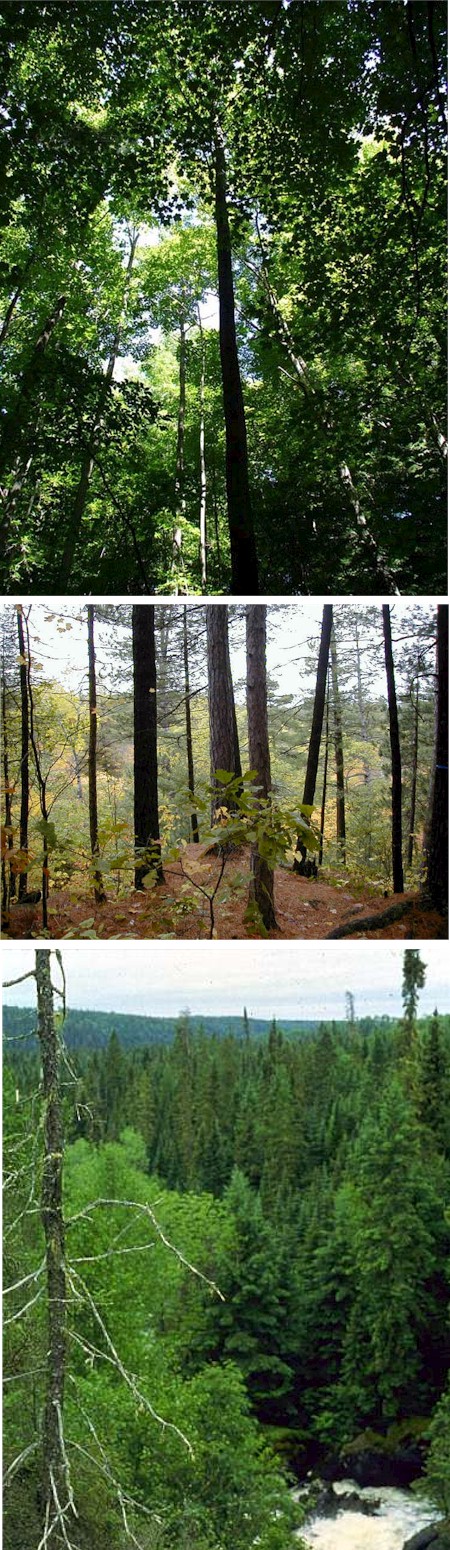

Usually I would see the track first, a vivid black line standing out against the lesser blackness, like the swath of a bulldozer. If I was closer, I could hear the animal’s deep hiss of breath and the sounds of her undershell scraping over logs. If there was a moon, I might see the light glistening off the parabolic curve of the still wet shell. Size at night is hard to determine: even the sprightly 180-pounders, probably nesting for the first time, looked big when nearby, but the 400-pound ancients, with shells nearly four feet long, were colossal in the darkness. Then when the excavations of the body pit and egg cavity were done, if I slowly parted the hind flippers of the now-oblivious turtle, I could watch the perfect white spheres falling and falling into the flask-shaped pit scooped into the soft sand. Falling as they have fallen for a hundred million years, with the same slow cadence, always shielded from the rain or stars by the same massive bulk with the beaked head and the same large, myopic eyes rimmed with crusts of sand washed out by tears. Minutes and hours, days and months dissolve into eons. I am on an Oligocene beach, an Eocene beach, a Cretaceous beach — the scene is the same. It is night. The turtles are coming back, always back; I hear a deep hiss of breath and catch a glint of wet shell as the continents slide and crash, the oceans form and grow. The turtles were coming here before here was here. At Tortuguero I learned the meaning of place, and began to understand how it is bound up with time. Ehrenfeld goes on to describe the cruel and careless treatment of the turtles by local fishermen, and how the witnessing of such atrocities by the President of Costa Rica so enraged him that he took steps to protect the green turtle’s Tortuguero breeding ground in perpetuity. Often, at night, I sit out on the back hill behind our house, overlooking the 1100-acre Albion Hills Conservation Area, with Chelsea the dog, just paying attention to the sounds and the smells and the shadowy sights in the moonlight. I soon forget there is a house behind me, and behind it a community of 34 houses interspersed with wilderness wetlands, and beyond it a city of 6 million that is forecast to grow to as many as 40 million by the end of this century. To us for a few moments there is only the wilderness, the sounds of owls and wood frogs and wind through the trees that have been here for a hundred thousand millennia — the dogwood and the balsam poplar and the maple and the trembling aspen and the white birch and white cedar and bur oak and ironwood and pussywillow, and the smells of rain and muskrat and decaying leaves. And I long to see and feel how this, my adopted home, this place that has welcomed me and allowed me to be a part of it and to share in its wonders, looked before man arrived to change it quickly and utterly. For even here, where nature is respected and where the actions of conservation authorities and lack (for now) of development stress has allowed some of this land to remain unaltered, and some more to start the slow path back to something like what it was like before we arrived, it still bears little resemblance, to the trained eye, to what it must have been, in the eons of silence and darkness before man arrived with his noise and artificial light and carelessness and altered it beyond recognition. If I am to believe the biologists, the area I call home once probably looked like these photos: I can imagine living in a place like this, but only because I do live in a place vaguely like this. If I were to have spent my whole life living in a city, or even on a farm, I don’t think I could imagine it. And even if I could, I don’t think I could conceive of it as my place, the place to which I belonged. While this is my adopted home, it is only, naturally, the place of a rare and scattered minority of humans, the First Nations, who learned, in ways that we never have and which I cannot hope to comprehend, to live with the bears and wildcats and mosquitos and black flies and bitterly cold winters and lack of year-round food supplies. Without my protection from these dangers and discomforts, I could never call this place home. So in order to make places like this habitable to us, as we destroyed the places in the cradles of human civilization that were habitable to us naturally, we had to reform them with our cities and farms, until they became unrecognizable, nothing like the pictures above — terraformed, civilized, converted to a dreadful sameness all over the planet. These cities and farms were as alien to us as they were to the creatures that retreated in their wake. When we try to imagine how bizarre it would be to live on a space station, or on the moon, we should consider that we have already made a much more profound and barren adaptation here on our suffering planet. But these cities and farms are not natural places for humans. They are not where we lived and thrived for three million years before their invention. Then we lived in the warm climates of Africa, of South Asia and of the Southern edge of Europe, when all those lands were heavily forested. We were and are, like all primates, creatures of the forest, and specifically of the tropical forest. And while three million years is but an instant compared to the hundred million years that the giant green turtles of Tortuguero have called that place home, that tropical forest is still the place our DNA tells us is our home, our place. Most of that tropical forest is now destroyed, cleared for cities and farms, and we have been gone from there so long that the thought of returning there even if there was room for us, which there is not, is too terrifying to countenance. So we moved from there to less hospitable and more dangerous lands and remade them into cities and farms as well: Since we could not live in these hostile environments we destroyed them and built ourselves artificial landscapes, vast alien prisons which protected us from the terrors of nature and weather but detached us completely from any sense of place. So now we are all homeless, six billion of us living in an artificial world of our own making. We have destroyed our own three-million year home and most of the homes and places of every other species on Earth, making them mostly homeless, too, those that we haven’t yet made extinct. I bow my head to the turtles of Tortuguero. They are so much wiser, so much more alive than we shallow newcomers to this planet can ever hope to be. They know the importance of place. They know how to live as part of a world to which all life on this planet once belonged. They show respect for the grand design of our fragile, troubled world, and know their part in it. While we are merely astonishingly fierce, wondrously adaptable, utterly homeless, arrogant beyond reason, hopelessly lost and addicted to the perpetuation of our own folly. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

Home.

First, “Know your place” sounds like what tyrants and slaveowners routinely say to their restless subjects.Second, who is this “we” who “wander the streets of civilization’s artificial world in a daze, never really home, wondering what is missing, why we feel so lost?” Speak for yourself, dude. You sound like those itinerant preachers who wander the streets in a daze, insisting that no one who doesn’t worship their god can ever really be happy. If you feel lost, it’s probably because you haven’t found the right crowd to hang with. That’s not “civilization’s” fault. Hell, “civilization” gives us far more means of finding kindred spirits than the hunter-gatherers had.Third, before you start using “addiction” as a metaphor, you might want to note that pushers don’t “seduce us back” into active addiction — our own sicknesses and messed-up priorities do. Pushers don’t “cause” addiction, just as “civilization” does not “keep us hooked on consumption and debt.” Stop looking for a (real or imagined) external entity to blame for your internal conflicts — that’s normally called “scapegoating.”Finally, if you think “Civilization is our ghetto,” wait till you try living in the wilderness with none of the physical, cultural or intellectual benefits that civilization has brought us these past few millenia. The fact that you’re still on the Internet proves your unwillingness to try that alternative. Not really so bad here in the “ghetto,” is it?

Raging Bee,To me, it sounds like you are missing the point he is trying to make. That and it seems like you are really on the defensive, like you are backed into a corner. This isn’t a situation where anyone is “right” or “wrong.” This is a community where we are all wrong and we are trying together to become less wrong and thus closer to the truth of what is actually happening.When I read his blog today, I take “place” to have two different contexts. The first is that I think he’s trying to suggest that since we came from the more abundant areas such as the rainforests in Africa and South America that evolution-wise that might make the most sense for us to live since we are evolved to best handle it. Unfortunately civilization has made us weak and we would have a hard time readapting. The second and more significant context in my mind, is that place means our place in the system (nature/the world). It is used like Q: “What is George Bush’s place in the government?” A: “George Bush is the president. He interacts with a different species called senators in X fashion. He interacts with representatives in Y fashion. He accepts input tax dollars and converts it with AA% efficiency into these different outputs.” So that begs the question,”What is our place in the world?” Is our place to consume all the worlds resources as fast as possible, so that their will be none left for our children or any of the other species on our planet? Does our place require us to build institutions that limit our interaction with this beautiful planet we have? Does it require us to “work for the weekends?” Do other animals “work for the weekend?”If there was no product to be addicted to what would happen to those that were addicted? Is it appropriate to blow cigarette smoke in the faces of those who are trying to quit or to give free drinks to recovering alcoholics? We are a society that doesn’t know what it’s like to live without civilization. We can’t even imagine life without our precious “cigarettes.” Even if you want to assume that they aren’t pushers and instead label them as enablers, you still end up with the result that these enablers make it easier for people to continue their self-destructive behavior. If there were no cigarette companies anymore and everyone had to grow the tobacco, process it, and then roll it, I’m pretty sure people would find it easier to quit. Escaping the debt cycle is certainly possible and you aren’t confined to it, but it is a significant undertaking, which many aren’t prepared to handle. It is also only applicable within a system that allows it. Nature doesn’t have “debt” You either have it or you don’t. So in that sense debt is unnatural and is a man-made product. We could just have easily written society to not have debt. So likewise while you can state that being in debt is our own fault, the problems it creates are a direct result as to how we chose to set up our society.As far as your whole last paragraph, that’s exactly what he was talking about. He’s just not saying it with the same overtones you are using. I think his overtones can be felt by imagining what it’s going to be like if civilization crashed for some reason or another. We wouldn’t have the power for the internet or for automobiles. We wouldn’t have farms that could produce enough food to feed everyone. In essence we would have to relearn how to live in harmony with nature or else we would face extinction as a species, or at least a dramatic reduction in our numbers or standard of living. The problem is that we are in a poor position to live without civilization, and civilization isn’t a guarantee especially with the choices our society is making. So the only answer that makes sense is how do we create a civilization that can live with harmony with nature, so that we don’t prematurely extinguish ourselves. Thats just how Io see it though

Yawn. I love hostile bloggers. Love them.I wonder what it is that encourages people to wander into one another’s houses and spraypaint graffiti on the walls, and then leave a trail to their own homes on the way out…

Check out Stephen’s pictures — amazing stuff. Medaille — bravo, thanks for trying, but I think Justin is right — when the worldview of a reader is so different from that of the writer, there’s not much point in trying to explain.

Regardless, Dave, a beautifully written and referenced post!

Don’t you see? Its all in your head. This is not reality you speak of. Forgiveness is freedom Dave. Also… do you own the Metallica “Black Album?” If not I highly recommend you give it a listen, you might enjoy it.

I loved the piece on the turtles. Thank you for sharing it.

By the way, the power point on energy production and consumption was a great link too.