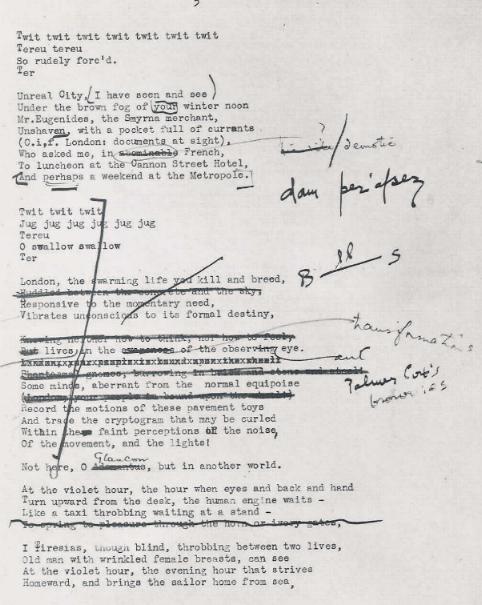

“…And so each venture Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate With shabby equipment always deteriorating In the general mess of imprecision of feeling, Undisciplined squads of emotion. And what there is to conquer By strength and submission, has already been discovered Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope To emulate – but there is no competition – There is only the fight to recover what has been lost And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss. For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.” — TS Eliot, Four QuartetsThere’s a new book out by Salon columnist and contrarian feminist Camille Paglia that contains 43 “of the world’s best poems” (from Shakespeare to Joni Mitchell) and Ms. Paglia’s guide to their understanding. When I first saw it I shuddered: I remembered school days when we got passing or failing grades in English for our answers to questions like “What did the poet mean when s/he wrote…” My taste in poetry, as in all the arts, is amateur, eclectic and probably unexplainable. I have a weakness for dark imagery, for irony, for clever juxtapositions of words that probably create unnecessary ambiguity. I began to take it all less seriously after I took a literature interpretation question from my teacher to the author of the passage in question, and he ridiculed the absurdity of the question publicly in a humour column in the local newspaper the next day.I still have this fear that dissecting a poem will kill it. But I did enjoy reading the original manuscripts of TS Eliot’s The Waste Land (sample page above), with the aggressive editing of Ezra Pound and the gentler suggestions of Eliot’s wife shown on each page. I enjoyed reading them not because they enhanced my understanding of the meaning of this remarkable work, but because they gave insight into the collaborative process of writing it. I am sure there are nuances of meaning I am missing, that I could pick up if I studied it more carefully, but that doesn’t matter to me: It’s the way it sounds that I love, the way in which its words elegantly articulate what I realize I think, and tease out and amplify what I discover I feel, in a way that I do not care (or perhaps do not dare) to analyze. The rest, as Eliot said “is not our business”. Does it matter if the reader misinterprets the writer’s true intellectual and emotional meaning? Is it even possible for the written (or spoken) word to convey intellectual meaning with any high degree of precision, or emotional meaning with any precision whatsoever? Look in the right sidebar and you’ll find the songwriters (usually mostly female) whose work I have listened to most in the past week. I know the words by heart, and these songs have tremendous emotional meaning to me, but I doubt, given the incredible ambiguity of the lyrics, and even given the power of the music and voice inflection to convey emotion, that this was the precise meaning the songwriter intended. I recently heard that kids 13-17 search for music more often than porn on the Internet (the only age group with that distinction) — now that’s meaningful. But my guess is that the mix of chemicals that flow through the body and brain of each listener, triggered by a particular song, and hence the emotions that are felt or understood by each listener, are utterly different. The sense of shared emotional experience at a music concert (or poetry reading) is likewise, while powerful, surely illusionary. I have looked at my last.fm “neighbours” (the people whose taste in music, according to the software, most closely resembles mine) and noted how many of them are my age, my gender, and my nationality — put us all in a room without our beloved music and, I’d guess, the silence would soon be deafening. We’re listening to the same stuff, but ‘hearing’ it completely differently. And so with poetry. Perhaps then, poets should spend less time trying to be emotionally precise, and, while remaining authentic, focus more on the cleverness (in the positive sense of imaginativeness and thoughtful craftsmanship) and the emotional power of words by themselves and in particular juxtapositions and well-paced phrasings. To use a cooking metaphor, perhaps they should focus more on the quality of the ingredients and less on how they (seemingly) work together. Here are three poems by the wonderful (in my opinion) contemporary poet Jack Gilbert (probably a violation of copyright, so I hope Mr. Gilbert excuses my use of them as examples): The Abnormal Is Not Courage (by Jack Gilbert) The Poles rode out from Warsaw against the German The Forgotten Dialect Of The Heart (by Jack Gilbert) How astonishing it is that language can almost mean, Rain (by Jack Gilbert) Suddenly this defeat. I have been easy with trees It is perhaps helpful but not essential to know that ‘Michiko’ is Gilbert’s deceased wife. Or that Gilbert is now 81, once celebrated but now largely ignored. Or that he’s been accused of misogyny. Or that his home town was Pittsburgh but he spent much of his writing life living modestly, in Europe. You can find lots of criticism and interpretation of his work online, but most of it is pretentious and dreadful — no wonder he fled and has chosen to write little in his later years. My only comment on his work is that it is well-crafted and evocative. I picked his work here because I think, for that reason alone, it lives up to e.e. cummings’ enormous charge to poets: A poet is somebody who feels, and who expresses his feelings through words. Almost anybody can learn to think or believe or know, but not a single human being As for expressing nobody-but-yourself in words, that means working just a little harder than anybody who isn’t a poet can possibly imagine. Why? Because nothing is quite as easy as using words like somebody else. We all of us do exactly this nearly all of the time – and whenever we do it, we are not poets. If, at the end of your first ten or fifteen years of fighting and working and feeling, you find you’ve written one line of one poem, you’ll be very lucky indeed. And so my advice to all young people who wish to become poets is: do something easy, like learning how to blow up the world — unless you’re not only willing, but glad, to feel and work and fight till you die. What is the purpose of all this toil, this “raid on the inarticulate”, this “fight to recover what has been lost and found and lost again and again”? My sense is that it is the same reason that solitary* crows sing to themselves, sometimes in their own voice, sometimes mimicking the sounds of others, even mimicking the sound of running water and wind: To keep company with themselves, to send messages to the rest of Earth, to anyone who is listening, to create something new, to find their own voice, to think out loud, to express themselves fearlessly and shamelessly. It is natural, insuppressible, our way of saying “Hello world, this is who I am!” And now we no longer need to fear the decline of this noble work in the inexhaustible frenzy to be busy and to be commercial: The Internet, and blogs in particular, have given us, poets everyone, back our voice. * Most crows, except each murder’s self-selected breeding pair, remain bachelors all their lives, and often overnight alone, farfrom their flock. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

Exactly. Wonderfully said, Dave. I give up, lapse into despair, when someone says, “But what does it MEAN?” I hear that more about films than poems, but only because we discuss films much more often than poems. The argument’s the same, though. When I see a great film or hear/read a great poem, I’m usually silenced. Either that, or I want to tell everyone on the same wavelength to see the film or read the poem. Your penultimate paragraph is poetry.

I second that, and would add that the footnote is more poetry. Also, I would always prefer to discuss the way that a poem or story is put together, rather than what it means. (I didn’t know about bachelor crows.)

Always happy to find another Gilbert fan. “Rain” is one of my favorite poems.

You are all so kind! Glad to see the “Rain” brought out the poets in the blogosphere.

Great to see Gilbert finally getting some mainstream recognition (if any part of poetry can be considered mainstream), although he’s still very much a word-of-mouth discovery for most. I find his interviews to be as hilarious as his poems are poignant.