“We are a generation weighed down by a sadness we don’t know we feel,” writes Melissa Holbrook Pierson in The Place You Love is Gone, the latest book to lament the loss of the importance of place in our lives. [Orion has an excerpt.] “We are a generation weighed down by a sadness we don’t know we feel,” writes Melissa Holbrook Pierson in The Place You Love is Gone, the latest book to lament the loss of the importance of place in our lives. [Orion has an excerpt.]

“An accounting of home is an inventory of loss”, and this book is Melissa’s personal and poetic inventory of the loss of three places in particular: The Akron OH of her childhood, the Hoboken NJ of young adulthood, and the towns of New York state leveled and flooded to create reservoirs to slake the insatiable thirst of New York City. “What we are is where we have been. That is all there is.” The book is an interweaving of three things: poignant reminiscences from her past of things that have been destroyed to make room for ‘progress’, angry tirades at human foolishness and thoughtlessness, and horrifying statistics at what we are losing to make room for more people and their possessions: America has paved 3.9 million miles of road, equivalent to 157 times around the equator; for every 5 new cars we make, a football-field-sized bit of land gets covered with asphalt; 3 million acres of open space are ‘developed’ each year in this country; farmland is lost at the rate of 2 acres per minute; someone just entering middle age now who grew up in, say, Rockland County NY lived in a place with 17,360 acres of farmland — now there are 250 left, but check back in a few minutes. We can only compile the statistics and get out of the way, dumbfounded. No one knows what to do about it. There is nothing to do about it.

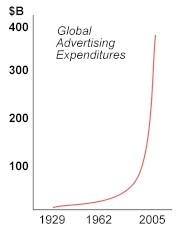

Melissa also reveals what is spent each year to convince us against all reason that all this is on the right track, illustrated in the graphic above. As Josh Buermann puts it “It costs almost nothing now to produce a pair of bluejeans but an astronomical amount to convince me to buy them.” Our sense of place is what orients us, and provides context for our lives, from birth: “Here the baby traces the map of mother’s face with his fingers, over rills and crevasses and seismic disturbances. He feels them with an intensity that does not even recognize their separateness from his own regional being.” We are all a part of the places we live within, and when those places are destroyed, a part of us dies with them. “You might have an easier time of it if someone would just acknowledge the fundamental existential tragedy of more driveways, of what is lost and how it hurts to know that it will never come back…Cognitive maps, formed by the brain upon first viewing a place, really don’t like to be changed, as scientists who have studied the way we find our way have learned.” Although Melissa’s stories are touching, and will probably resonate with some of your own stories of places lost, the real power of the book is in its poetic laments for what all of this means, writ large, multiplied by six billion. After all, while loss of place at the local, personal level is (literally) unsettling, even devastating, loss of place at the global level is catastrophic: We are trying to be what we are not: every other species that has inhabited the same ecological niche for hundreds of thousands of years without the need for an eight-bedroom house where three used to do. We alone do not emit those mysterious pheromones that slow procreation when the carrying capacity of the land has been reached. Our neural pathways were formed by millions of years of existence in communities of our fellows where daily congregation and rituals and exercises made us what we became, and thus whole…

Something gets into you, and you want to yank on the collars of people in the street until their eyeballs make noise. You mean to horrify them with the news, amply documented if they cared, that the earth is pretty much a goner. What you do instead is convince them of your lunacy…Suddenly now it hits, bizarrely easy to grasp. We are inexorably headed for the Big Goodbye. It’s official. The unthinkable is ready to be thought. It is finally in sight, after all of human history behind us. In the pit of what is left of your miserable soul you feel it coming, the definitive loss of home, bigger than the cause of one person’s tears. Yours and mine, the private sob, will be joined by a mass crying: whole cultures, ways of life, languages, beliefs, landscapes, climates, now falling at a cataclysmic rate along with millions of trees in the Congo basin and the Brazilian rainforest and along the Mongolian border. The echo of their crashing is a prelude to the final kiss-off, the extinction of our species along with every other that is made to suffer by us… There is not a power upon the earth that will stop progress. Except progress itself. When the air can’t be breathed, when the psyche starts running amok from too many others crowding the elbow, when the spring comes four weeks too soon, when the floods come, when the trees wither, when the billion diverse creatures that weave together in ways we cannot comprehend to make the net that holds us up die, when selfishness calls the chickens home to roost, then it will stop. Too bad we won’t be around to celebrate our triumph over ourselves at last. She is saying, of course, what John Gray says in Straw Dogs, but arrived at from a different train of thought and feeling, and expressed in a different voice: That our civilization has entered its final century, and that there is no stopping it from bringing about its own demise, as all civilizations before have done, smug in their belief that they are somehow different, unique, immune to the inherent failings of empires built on the presupposition and need for endless growth. Melissa talks about the sense of “weird happiness” she feels at each piece of news that reaffirms the validity of these feelings of “lunacy” — that the terrible reign of human animals on this planet is nearing its end. We feel it first in our bones, an instinctive sense of dread and foreboding. Then we feel it emotionally, the sense of loss and grief and anger and guilt, that wells up with each March of the Penguins, when what Gray calls our biophilia, love for all life on Earth, smashes into the growing realization that all that life is dying at an accelerating and unstoppable rate. And finally, we make the rational case, which we keep to ourselves, because what is the point in pointing out what is obvious to those ready for such awful truth, and unfathomable to those who are not yet ready, who still think the cure for the addiction is more of the drug? Women seem to be further along this curve of understanding than men, if more reticent to articulate it publicly (do they talk about it among themselves, in private? — I suspect not). Perhaps this is because most women are more intuitive, more grounded, less abstracted, and more in touch with their emotions than most men. They are also, mostly, more accepting than men, better suited to make the best of what is, instead of trying to radically change it. I used to think that was meekness, but now I see it more as canniness, ‘knowing better’ than to expect to change what cannot be changed (though it doesn’t stop them from trying, and hoping) — pragmatic instead of idealistic. That is not rewarded much in this world, but it makes sense. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

“Place is security, space is freedom; we are attached to one and long for the other” (Yi-Fu Tuan, in “Space and Place: the Perspective of Experience”). It seems we’re losing both our places and our space; little wonder then that we’re losing our security and our freedom.I think, however, that Melissa is slightly off the mark when she claims, “We alone do not emit those mysterious pheromones that slow procreation when the carrying capacity of the land has been reached.” I think she’s right in saying we don’t have those pheromones, but something else slows reproductive rates in rich countries (possibly the conflict between the lust for possessions and the costs of raising children); she’s also right in saying the effect doesn’t happen when the carrying capacity of the land has been reached: it happens when it’s been substantially exceeded.I know very well what she describes as that “weird happiness”. It’s not a delight in our impending downfall,nor any kind of misanthropy; more a kind of comfort in the knowledge that the world will eventually readjust. But I guess many would dismiss this as fatalism.

Dave,Nicely said. You write well. Thank you.Tom S.

I’m not so sure about you conclusion that women would be better at sensing and accepting the unavoidable better than men. My experience has been that women try to change others and their circumstances way past the point of no return, then they jump off the sinking ship wondering how they got there and why they did not manage to effect change on time. Meanwhile, men just carry on with business as usual and cross the bridge once they get there.

Martin, I’m sorry to hear that you have had such unpleasant experiences with women!Dave, I wanted to let you know that the women I know do talk about the dangers of inculcating young people into consumerism — especially the mothers I know. We cringe each time our children receive plastic gifts that they will only use for a while, and then we have to figure out how to sort and store away, or recycle, said gifts. This is especially hard when children in our society develop such personal possessiveness so early!-Sandy

I was born and lived in India for the first 22 years of my life. You would think that would surely be a strong enough foundation for establishing a