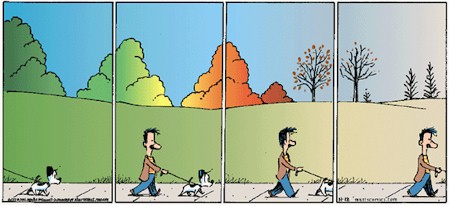

Another of Patrick McDonnell’s Mutts strips Patricia McConnell’s book For the Love of a Dog is one part training manual and one part love story. It is a study of the behaviour of our companion animals and of ourselves, but mostly of our relationships with each other. Much of the early part of the book is about dogs’ body language and what it tells us about their emotional state. McConnell concentrates on four primal emotions: fear/anxiety, anger, joy and love. Here is a summary of the signs (the book has photos that illustrate them):

Just as we need to be observant of dogs’ body language, and careful to note the signs rather than projecting how we would feel (or think we would feel) in their circumstances, we also need to be aware of our own body language and how it is being interpreted by, and influencing the emotions of, our dogs. That means we should avoid wearing sunglasses or large hats that can conceal or misrepresent our feelings, approach dogs we don’t know as they do (from the side without making direct eye contact, walking loosely with mouth open and relaxed, breathing deeply and evenly, and cocking our head). We can be sure that, though we may be unobservant and inattentive of dogs’ body language, they are very attentive to ours. We also need to avoid gestures and words that mean nothing, or different things, to animals. Hugs, for example, are generally distressing to dogs, since they block view and constrain movement and hence are ambiguous in meaning to dogs. When our words say one thing but our tone of voice or body language conveys something else, the dog will respond to the latter, even when the words are those s/he has been trained to recognize. McConnell has no use for the show-’em-who’s-boss school of training that has recently come back into vogue. There is no substitute, she says, for positive reinforcement and gradual, patient repetition of lessons, not to the point of intellectually exhausting your dog. As I read this book, it occurred to me that everything McConnell says about how we signal to and relate wordlessly to our animal companions applies very much to how we relate to other humans as well. “Accurate, objective observation is a skill that requires practice, but it starts with asking your mind to focus on what you see, not on what you think it means”, she writes. This is precisely the instruction we are given in cultural (and customer) anthropology training, to learn to better appreciate and understand our fellow human beings. And she goes on to explain in Lakoffian terms how we can misinterpret our dogs by failing to get outside our own ‘frames of reference’, describing a woman who was convinced her dog’s misbehaviour was an attempt to ‘test’ her, when it was merely a reflection of the dog’s ignorance that that behaviour was not acceptable. The latter part of the book explores the four primal emotions. The chapters on fear explain the Darwinian advantage of shyness/fearfulness (shades of my last post) but note that shyness combined with other traits can lead to aggressiveness. Fear can be genetic, nurtured (deliberately or accidentally), or the result of trauma. Genetic shyness can be overcome with gentle, gradual, patient conditioning. McConnell explains how to do this in the context of dealing with separation anxiety and excessive barking when someone comes to the door. The chapter on anger/hatred presents an interesting hypothesis that fortunately doesn’t extend to humans: Competition as puppies for mother’s milk and attention teaches a tolerance for frustration, and puppies from a ‘litter of one’ tend to be intolerant of frustration and prone to outbursts of anger/hatred as they grow older unless they are carefully trained. A good test is to gently roll a relaxed puppy after play over on his/her back and hold him/her in that position for a short while — puppies that become very aggressive in this situation will likely be difficult to handle as they become full grown. Just like some people, some dogs need to learn anger management, and this requires considerable expertise (a series of progressive, positively-reinforced ‘stay’ exercises for impulse control is explained in an appendix to the book to help with this). The danger here is that dogs will learn from the model we show them — if we show anger in our training and response to them, it will reinforce the acceptability of such behaviour, no matter what we do to discourage it. The chapter on joy/happiness lays out the conditions that make our dogs happy: fresh water and good food, of course, but also companionship, physical and mental exercise, consistency and clarity in our behaviour toward them, respect for their individuality, physical contact (at the right times, the right way in the right places), and a sense of security. Our happiness and theirs is mutually contagious and self-reinforcing, and, as with humans, sometimes the anticipation of happy events is as joyful as the event itself (which is why the ‘clicker’ employed just before a reward is given, works so well as a training tool). The final chapters deal with dogs’ capacity for love, jealousy, grief, self-awareness and problem-solving. Of all the personal stories in the book about McConnell’s beloved dogs, the one I found most moving (perhaps because it reminded me so much of my story and feelings about Chelsea) is one of the last. Here’s an extract: About a week before [Luke, suffering from debilitating kidney failure as a result of a lengthy tick-borne bacterial illness] died, I began to feel that my efforts were harassing rather than helping him. Accepting that I couldn’t save him, I switched to hospice rather than hospital care. I emptied my calendar and spent my last week with him, soaking up the touch of his nose, the smell of his fur, the pink of his tongue. I sat long hours with him in the sun up in the pasture, full of the bittersweet emotions that accompany love and grief. At the end, we slept together in a makeshift bed on the living room floor. That’s where the veterinarian and I helped him pass on, peacefully snuggling up against me, nothing but bones and a shockingly beautiful black-and-white coat.

After Luke died, I was dumbstruck with grief, stumbling through the next months in a haze. I felt as if I’d been hit by a train, as though I’d been physically as well as emotionally injured. None of my senses seemed to function as they had before. The colors of the earth were different, wrong somehow, although I couldn’t quite say how. I coped well enough, seeing clients, running my business, tending to my farm. But a day didn’t pass when I wasn’t heartsick and hurt and angry, and that I didn’t agonize over whether there was something I’d missed, something I could have done to save him. McConnell goes on to relate evidence of the immense grief experienced by Lassie, another of her dogs and Luke’s best friend, in the months after Luke’s passing, laying to rest any doubt that animals feel the same emotions, and in their own way at least as deeply, as humans. This is a book for anyone who wants to understand our animal companions better, either to solve behaviour ‘problems’ or just to begin to fathom our own species and its relationship with the natural world. In his books, Jeff Vail talks about how the world is better represented by connections than by the things connected, and McConnell’s book is mostly about our connections with dogs, and through them with nature, and our true selves. Read it and discover how much we can learn from, and feel mutually about, creatures who have no need for our strange and imprecise tool of language. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

Oh, this is a *wonderful* book! And so interesting to read your quite analytical review having read it a few years ago myself and remembering now only the “story”. Thanks for the reminder that I must dig this one back out of my shelf to pass along to one of my dog-loving friends.(And, enjoy yourself in London!)

Fascinating. I have automatically approached an animal I didn’t know like this but reading it makes sense to a conscious level.

While McConnell makes the case for dogs having emoti (something I think every pet owner knows intuitively), there is one scientific study that showed that dogs had the same neurochemical response to interaction with their people as the people had. When dog and human played and cuddled, the brains of both released oxytocin, the neurochemical that creates the experience we call love. If you accept that emotions involve physical states (the accepted scientific explanation), then you can say that dogs share this emotion.