George Siemens’ online book Knowing Knowledge is fun to read: It’s laid out like a Tom Peters book — full of graphics and different type fonts, and some wonderful quotations1. It has a kind of stream-of-consciousness style that’s a bit McLuhanesque. It’s playful. I resisted the temptation to take notes and synthesize it (perhaps because I read it on-screen), although I thought it sometimes presented concepts awkwardly and had a few glaring omissions. For example, after saying he doesn’t believe in categorizing, he presents a set of categories of knowledge — knowing about x, knowing how to do x, knowing how to be x, knowing where to find x, knowing how and why to transform x — but omits knowing who knows x 2). At the end of the first section of the book he presents these knowledge/learning ‘principles of connectivism’:

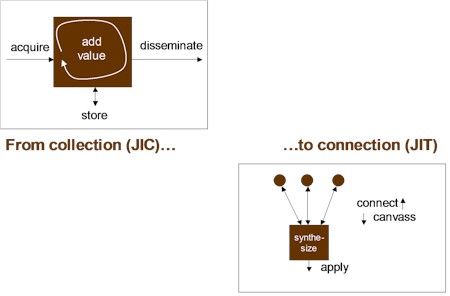

A healthy learning environment, he says, is open, self-managed, fostered, and conducive to knowledge flow. He implies, as I have argued, that ‘just in time’ learning is usually better than ‘just in case’ learning, and that collaboration, receptiveness, engagement, pattern-recognition, direct experience, and sense-making are essential or conducive to the learning process. Siemens introduces the concept of ‘context games’ — interactions where our understandings and filters ‘compete’ in our (and other conversants’) contexts for our (and others’) acceptance. This is all interesting, but after awhile you start to ask yourself how it can be useful. As fascinating as his theories and models are, I was hoping for something of practical value comparable to my contrasting of the old 1990s ‘acquire, store, add value, disseminate’ and the new 2000s ‘connect, canvass, synthesize, apply’ models of knowledge management: In the second part of the book, Siemens describes how the principles he outlines in the first part might be applied. As I outlined in my earlier article, the approach he suggests to improve knowledge-sharing and learning in organizations is evolutionary and iterative rather than imposed. It responds to needs as they emerge rather than pre-supposing what those needs are. It demands a deep knowledge of the current state (which requires going out and talking to and observing people on the front lines to see what is really happening in their use of information and technology, and appreciating what they need and how they learn). It is a continuous process rather than a disjoint series of projects and ‘releases’. It is focused on developing competence and capacity, rather than just increasing the volume of information flows. For all of these reasons it is superior to the methodologies that have been Standard Operating Procedure in KM for more than a decade. As the illustration at the top of this article shows, this approach is cyclical, two-way, and accommodates the needs of both managers and front-line staff. Change is perceived to be a consensual process: Only when there is a consensus that change is valuable will it “take root”. The four change enablers in the graphic operate almost like a pendulum: The demand for change (usually from customers, sometimes from management, sometimes from front-line workers’ learning and adaptation) precipitates ‘affordances’ (possibilities, ideas, alternatives and potentials) which, in turn, if they can achieve consensual traction, precipitate structural, systems, and infrastructure change within the organization, which, in turn, finally produce new methods and processes — different ways of doing things in the organization. Or, in other words, needs -> possibilities -> change programs -> new processes & tools. Then, the adoption of these new processes & tools (often in unanticipated ways) yields new change programs and raises new possibilities that evoke new ëneedsí. Through several iterations (swings of the pendulum) all four elements converge on a new stasis, until new needs and change pressures restart the process. A healthy knowledge ecology (knowledge-sharing environment), Siemens says, has the following attributes: flexibility, diversity of tools (for obtaining content, context and connection), consistency and sufficiency of time and attention, trust, simplicity, encouragement, connectedness, decentralization, and tolerance for experimentation and failure, with ëspaceí for experts and novices to meet, self-expression, debate, dialogue, search for archived knowledge, structured learning, communication of news, and nurturing of ideas. Networks form within such ecologies, and provide better knowledge and learning environments than hierarchies: As Siemens said (better, I think) in another article: The desire for centralization is strong. These organizations want learners to access their sites for content/interaction/knowledge. Learners, on the other hand, already have their personal spaces (myspace, facebook, aggregators). They donít want to go to someone elseís program/site to experience content. They want your content in their space…When we try and create Communities of Practice (CoPs) online, we take the same approach ñ come to our community. I think thatís the wrong approach. The community should come to the user.

In the same article (and also in the book), Siemens eloquently describes the way in which knowledge/understanding emerges in social, ecological and other complex environments, much to the consternation of organizationsí command-and-control types: We have a mindset of ìknowing before applicationî. We feel that new problems must be tamed by our previous experience. When we encounter a challenge, we visit our database of known solutions with the objective of applying a template solution on the problem. I find many organizations are not comfortable suspending judgmentÖInstead of trying to force these tools into organizational structures, let them exist for a while. See what happens. Donít decide the entire solution in advance. See the process as more of a dance than a structured enactment of a solutionÖThe view that we must know before we can do, and that problems require solutions, can be limiting in certain instances. Knowing often arises in the process of doing. Solutions are often contained within the problems themselves (not external, templated responses). And problems always morph as we begin to work on them.

Part of my responsibility in my current contract assignment is increasing the awareness and accessibility of the available tools, content and other resources among our employees and customers. Thereís a strong temptation to ëprescribeí how and when these resources should be used (as I did with my communication tool decision tree), but while these ëprescriptionsí may be useful guidance (especially for novice users) it is important that we allow and encourage employees and customers, individually and collectively, to use these resources as they see fit and share their ëadoptionsí with others, and understand and accommodate rather than proscribing their problem workarounds.

Siemens calls for the redesign of organizations3 to enable decentralization and networked knowledge transfer, learning and action, but in large organizations this isnít going to happen ñ it will only occur, haphazardly, around the ëedgesí of organizations where those high in the hierarchy canít see it happening. Although his prescription is, I think, impractical, his vision of an organization that enables effective knowledge-sharing, learning and collaboration is worth thinking about. Iím working on an article on ëworkaroundsí as the means by which most useful ‘unmechanizable’ work in organizations (i.e. thoughtful ëknowledge workí) actually gets done. Knowing Knowledge could be used as a ërecipe bookí of workarounds by savvy, practical knowledge workers. If, as Siemens says, solutions are often contained within the problems themselves, then thatís a step in the right direction. Notes: 1. Examples:

2. He later seems to imply that “know who” is a special type of “know where”. 3. The redesign process has eight steps: Current state analysis, representation/evaluation, validation, learning/knowledge strategy (ëdevelopment mapí), ecology design/deployment, nurturing learning capacities/processes, assessment and revision. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

I think the cuteness wins me alone.

It’s a long post and I haven’t read it all, but what catches me most is the small text:Current state analysis, representation/evaluation, validation, learning/knowledge strategy (

“Our slogan is: you can talk when you need!Thare is no problem what we can not solve.game“

I am convinced that together we know everything that any one of us needs to know. Further, I think that making a learning game together can be a useful structure for us to think together with. Siemens has inspired me too.I have set up a wiki and a blog for nonprofit social entrepreneurs to make an elearning game together to solve the mystery of earned income profitability. Please explore. Let me know what you think.

Interesting that you highlight ‘know who’ as a missing component – IMO this is a critical element and the key to awareness, info overload and finding answers. Paying attention to personal networks, connections and relationships is a key knowledge practice for the individual, group or organization.Also wonder if the shift to immediacy is as great as George seems to portray – I do not believe the nature of knowledge itself has changed just the way and lens we use to observe it.