Artwork from Kate Bush CD A Sky of Honey, via Andrew Campbell In an article last week, I described Jungís four orientations for learning, understanding and seeing the world:

I described artists as those particularly competent at the sensual and emotional orientations, and one of the notable capacities I listed under those of sensual orientation was storytelling. That’s because stories are detailed creations, and require the journalist’s precise and perceptive attention to who, what, when, where, why and how, and ability to capture them in ways that speak to others. Stories are about telling what is (or was) from a particular perspective. As I thought about that I read this from Zane at Lichenology: I believe that art is central to the process of change that needs to happen in the world, but the connection is not straightforward. I’ve never been attracted to art that serves as a vehicle to deliver a Message. While it may have some value, it ceases to be art, in my eyes, and becomes propagandaóor just bad art.

I’ve struggled in my own creative work (I count four short, solo dance performances and a smattering of poetry as my small opus) to be relevant, but not preachy. I’ve wanted to stir people up, to stretch their perception of the world, and to raise questions without pretending that I have any pat answers. I find that in the process of creation, I have to turn off my normally active analytical mind or it gets in the way, always trying to make sense. Art ferments in the shadowy world of association and dream, not in the rational light of day. Like a mushroom, it draws energy from a vast tangle of subterranean mycelium and fruits briefly, sending out its spore to the breeze. Part of what I always wanted to create through performance was a common experience and a shared participation in meaning. Our society has perfected the separation of roles and the partitioning of experienceóthe separation of church and state, of mind and body, of performer and audience. It fits very much with our passive role as consumers, but it doesn’t bode well for the process of social change, where active engagement and renewal is needed. Good artists bridge boundaries, like the shaman of traditional cultures, crossing into a different fabric of experience and bringing back knowledge about how to heal human rifts and live in accord with some larger truth. The change that needs to happen in the world, like the best art, needs to be participatory. It is not a spectator sport. And like anything in which we fully participate, there is the possibility of falling short. So we stand back, we shy away from getting sucked in, preferring the endless possibility of distraction to the risk of engagement.

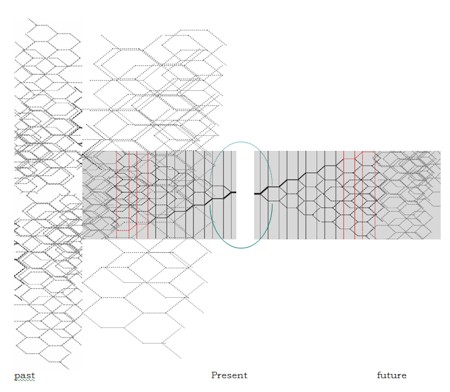

A major new focus of business is on storytelling, and, in the larger sense, adding context and meaning to information, precisely what Zane describes as the role of art as a ‘shared participation in meaning’. The essence of good storytelling is engaging the audience, drawing them in, transporting them, making them participants in the experiencing of the story, so they really understand its meaning. And so it is with art. In a sense, all art is storytelling, helping us to understand in a sensual, emotional, intellectual and visceral/instinctual way what ‘it all’ means. It is a bridge between the four ways of understanding and knowing. Some arts (novels, film) tell stories in a clearly linear way, while others (music, painting, sculpture) tell their stories holistically, non-sequentially. Why is it then that for most of the last century, there has been a growing dichotomy between ‘popular’ art (the mass media, including popular music, film and novels) and more complex art? We need to know this because if art is to be a vehicle for social change, it must be accessible and engaging to activists, to those who would take personal (Let-Self-Change), political, economic, social, educational, technological and scientific action as a result of the understanding that art brings them. The reason, I think, is not anti-intellectualism or (as Joe Bageant would have us believe) a dumbing-down of the population to the point complex art cannot be fathomed, but rather that its very complexity makes it inaccessible and ëunpopularí and hence not useful as a vehicle for social change. As I’ve said before, we loathe complexity ñ it offends us that elegant simplicity is usually an illusion, that everything is beyond our control and understanding, that effective things are inefficient and efficient things are ineffective to the point of dysfunctionality. We don’t want to work that hard. We do what we must, then we do what’s easy, and then we do what’s fun. There is no time or inclination for the complex. The mainstream media with their sound bites and reductio ad absurbum pander to our longing for simplicity, but they do not create that longing. We create the paradox ourselves (with some complicity of politicians and other corporatists) by filling our lives with difficult work (the work of making a living, the work of making love last, and the work of satisfying our needs of the moment). After all that exhausting work, to spend our ‘spare’ time on anything difficult is surely masochistic. And likewise, too many ‘artists’ donít want to work that hard either, especially when formulaic, unoriginal, amateurish ‘popular’ works can be so profitable, and complex works so unappreciated. The enormous popular success of most rap music, trash fiction, and some really mediocre blogs can only frustrate the true artists, composers, creators, investigative journalists, craftspeople and other hard-working ‘storytellers’ whose work requires an investment of time and energy that few seem inclined to give. We all want attention and appreciation, and few will persevere when the terrible and important truths we show the world are ignored and misunderstood. So what do we do, when none of us, not even those who appreciate the need to know and to act, has the time and energy to appreciate? To appreciate complex art or complex reality. Itís all just too hard. For example: Andrew Campbell sent me an image of one of his works (below) as an attempt to articulate the meaning of Now Time. Many of us try to interpret works of art on a strictly intellectual level, to ‘decipher’ it as if it were a puzzle. But complexity cannot be understood on that narrow level. We have to allow it to be internalized within us in its own way and in its own time, to ‘ferment’. We have to allow it to engage our senses, our emotions and our instincts holistically with our intellect. We have to think ‘about’ it. And in todayís world of instant gratification and attention deficit that is a challenging and unrewarded activity, and one that we are increasingly unpracticed at. Just as we must bear the responsibility for making this world as bearable a place as possible, a little bit better each day, despite knowing that our civilization is unraveling and that what we have done will be undone (though hopefully remembered by the few brave survivors of this century), we must, too, bear the responsibility for telling our stories despite knowing that few are listening and even fewer understand. This is nothing new. And so, we brave storytellers, each in our own way, continue to tell our stories as best we can, perhaps much as the cave artists did in the millennia before civilization, as the indigenous peoples did during the millennia of civilizationís hopeful dawn, and as the artists of the renaissances of our civilization did as that civilization churned forwards. We, artists all — painters, composers of music, sculptors, investigative journalists and many others — represent to the world the portrait of our civilizationís fourth and final turning. We ‘just’ tell its story. Whether its meaning will be understood and provoke needed action is not our business. Perhaps those who survive civilizationís end, and build a more joyful and sustainable society, will have the time and energy to appreciate what we do. And learn from the self-confessed mistakes that cry out in ourportrayal of our terrible world, and its terrible beauty. Category: The Arts

|

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

I doubt civilization is going to end, though it may for many people. Certainly the collapse of current governments and the destruction of many nations seems at hand. But there are forms of order and relationship which will survive–some family and church networks, some tribes, and some businesses have robust forms of governance which will continue. The centers of global power may well be places you are presently overlooking, though they aren’t hidden.And artists who are a bit less solipsistic–less isolated in the cultish adoration of “greatness” and “originality”–will trace the enduring themes through new circumstances and carry the sacred burden a bit farther down the road.

One way I think and feel abouI think of Art is as the creation of artifacts whereby my story reaches into your story, and reciprocally your story informs my story.

Jesus was a great salesman. He knew that it wasn’t enough to make an event that would convert to a good story. He knew the power of having evangelists to tell/sell it. That there’s power in telling something familiar (a baby was born) with a whiff of mystery (in a manger)and credibility (wise men came).A great preacher looking to convert beliefs/actions/thoughts slices complexity into chewable pieces–telling one parable at a time and tying it to something personal that the “audience” can related to. We can bitch and moan about how masses avoid complexity and change, but it doesn’t change the fact. Good stories are repeatable, and to be repeatable and viral, they need to be simple with a lot that’s familiar. They also need to shift a mood (laughter, horror, sadness) so that people FEEL the tale and the lesson in their body not just their mind.Effective art moves the viewer–who then says to another, “you’ve got to see this!”.

Jon – i like what you’ve written – would you loke to see how that maps very precisely back and forward in time over 5,000 to 10,000 years (pics and text)Andrew