A couple of weeks ago I weighed in on readers’ comments about my response to Dave Snowden’s argument favouring debate over dialogue, even when it produces some friction. I owe some further explanation and elaboration. My thesis on how we establish our beliefs, and how we learn, is as follows (based on nothing more than personal observation, and on an appreciation that this thesis makes some Darwinian sense):

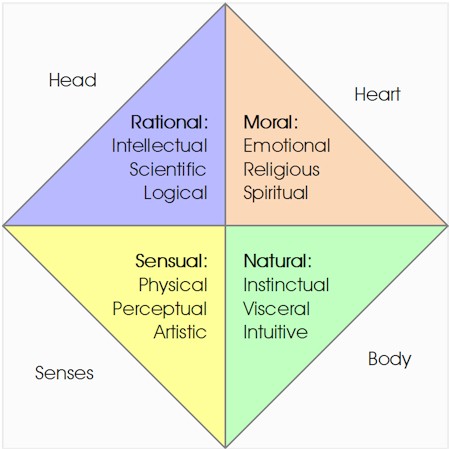

There is a strong psychological and emotional side to all this that defies rationalization. I think this is because our process for learning (internalizing knowledge), and the resultant process of forming beliefs, are complex. I’ve tried to illustrate this in the graphic above, which shows Jung’s four forms of learning and knowledge — sensual (through the senses), emotional (through the heart), intellectual (through the mind) and instinctual (through the body/genes). Conversations of all types (including debates and dialogues) are variously effective at helping us acquire these four types of knowledge:

These four accumulations of knowledge make up what we understand, and that in turn drives what we believe, and makes up our worldview, the frame through which we filter (i.e. assess the credibility of) all arguments and information.

There are several different types of conversation, each with a different effectiveness at imparting knowledge and therefore influencing our beliefs. Otto Scharmer has argued that there are four types, which he rates judgementally in increasing order of value as follows (I’m paraphrasing):

This is a tich new-agey to me (and I can hear Dave Snowden gnashing his teeth). As a model, though, is such a distinction fair, and is it useful? I’m not sure it is either. Debates need not be manipulative or selective in the information they introduce. Yes, debates are adversarial. They attempt to present two different points of view to allow the debaters and their audience to contrast the credibility of each. Our legal system thinks this is a good thing. So do those who think that advocacy ads (I just saw one by a BC anti-abortion group that masqueraded as a health advisory!) should be immediately countered by one providing a contrasting point of view. And debaters are often better prepared for conversation (they’ve put more effort into research) than participants in other types of conversation. But advocates of the alternative disputes resolution process think adversarial conversations are destructive and cause both sides to exaggerate the truth, lie, withhold information and try to coerce. Debaters can get caught up in their own rhetoric and defensiveness and stop listening to reasonable arguments for other positions. Some people like to debate purely for the pleasure of fighting and defeating an ‘enemy’ — they have no interest in learning. Brainstorming sessions and other conversations with either a creative or collaborative purpose are usually not helped much by adversarial discussions. I’ve argued before that a good conversation is like a dance, and a dance is a cooperative performance, not an adversarial one. The obvious conclusion is that there are some situations when a debate is the better form of conversation, and others when a dialogue is more suitable. There are certain protocols appropriate for both (the need for good research, and cues, signals and facilitation steps to disarm bullies, liars, manipulators and conversation hogs). What’s even more important is that we each achieve an understanding of our own worldview, our blind spots and our biases, and hone our listening, judgement-suspending, creative, imaginative and critical thinking skills. And of course, practice, attentively, our conversational skills. If we were all better at these things, it probably wouldn’t much matter which type of conversation we chose for any particular situation. My own point of view on all this? Well, in this article I’ve tried to present the arguments for both types of conversation, so while I don’t much like adversarial conversations, I can see the value in laying out the arguments for conflicting viewpoints. But if there’s a more peaceful way to get those divergent viewpoints on the table, I’m not much of a fan of debate. When I’m listening to and participating in a conversation, I’m internalizing more than just what is being said. I’m watching body language, tone of voice, word choice. I’m listening to what my instincts are telling me. Like those in aboriginal cultures, I’m filing all of this away to sleep on it, and to allow my subconscious knowledge to factor in before I any conclusions emerge. I’m thinking about what I want to do and see and read later as follow-up research. None of these things can be articulated well in a debate, but they’re all important to our individual learning. I love to be part of dialogues. But while I’m often attentive when others debate, I’m rarely willing to enter into them. That’s probably selfish of me — if I were more active in debates, others might learn more from me. I’m too preoccupied with my own learning, my own Let-Self-Change process, to be as generous as perhaps I should at helping others learn along with me. But I’m still practicing, and maybe if and when I get as good as Dave Snowden at debate, or as good as Chris Corrigan at dialogue, I’ll become moregenerous at both. Category: Conversation

|

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

No so much gnashing teeth David, as gently sighing ….Two points. Firstly your definiton of debate implies conflict and a desire to win. Debate can also be an exploration, especially if you take a position you do not personally support. It is a tool like dialogue. My argument has not been to say everything must be a debate, but that the new age fluffy funny dislike of it means that they are loosing a valuable learning tool. Secondly, we all (well some of us have) need to move on from Jung. This is poor science, and also classic 19thC categorisation. All of those factors are interwined. You cannot separate them into rational, emotional, spirtual etc. They have co-evolved over the race, and co-evolve during key periods of plasticitiy in the human brain. You mught like to read Lewis et al “A General Theory of Love” or Deacon “Symbolic Species” to provide some science here.

Different types of dialogue certainly can be more or less successful in discussing new/different ideas. In any one-on-one discussion, though, it is difficult to circumvent the reactive rejection to new ideas; just about everyone is hesitant to change the way they think about something, and in any type of dialogue this reservation will still be present.Writing (and to a similar degree, lecturing) provides a single-direction stream of information that has additional benefits. A written work is more polished, and sometimes longer, than a dialogue, but the biggest advantage in my mind is that it allows the reader to absorb and contemplate the information instead of rejecting it with the first opposition that comes to mind.Of course this is not to say that dialogue has no purpose. From my personal experience, though, writing has a certain advantage in introducing a new idea in a way that lessens the automatic generation of opposition.

Very interesting post, Dave. I was a debater in high school, but generally I find debate most worthwhile in the context of a protracted conversation, which is where the Snowden post started. The purpose of debate is to persuade someone about your point of view, which in the listener often prompts reactivity for some of the reasons you mentioned. I am interested in listening to debates to rationally solve problems I am engaged in, or to seek support for my own position. I also happen to like learning about positions contrary to my own. For example, an artist/blogger I find interesting is skeptical about global warming, and it seems worthwhile to know why.The purpose of dialog is primarily to establish a connection with someone, and then secondarily to clarify issues or solve a problem. So called dialog fails for all the reasons you mention–a person may say they want dialog when in reality they want to persuade you they are right about whatever it is. It takes some conversational skill to be able to signal to your co-conversant that you have actually heard what they said. If someone has actually heard my views, I am more receptive to a challenge. I am very interested in this subject both because I work on social change issues, because good conversations offer inherent pleasures, and because constructive conversation and debate (people connections) is a building block for a more sustainable society.

Nice way to dissect types. Without having explicit articulation, reading that I see I’ve been gravitating and seeking #3 and #4.

Bohm noted the discussion, liker percussion pointed to a tendency covered in debate to some extent ( of a knock about) which he felt was not as useful to us inresolving and creating solutions to problems deemed in need of that.Debate can be hilarious. Some people, like do Bono (i think) see humour (a sense of) as a sign of higher intelligence. I think humour does serve i high end value – releasing tension, utilising the imgination and to some extent unconscious faculties ( or sub-conscious) …i seevery little humour in these exchanges between so called self professed experts on how people should communicate effectively. I don’t know how it is with ‘good’ language as written or spoken – making and appreciating art in my domain of interests involves both knowledge, learning and a good deal of suspension of conscious modes of recepton and judging so as to open the door to the knew.The word i always miss in these exchanges is imagintion. I think a lot of great communicators and creators had a high regard for imagination ;-) On a more prosaic level – maybe one of you could access, is a little essay on rembrandt that i posted at LO many moons ago. In it is a (i think) profound message from Rembrandt to us today via a kind of transfiguration – embedded in his work. Jost a few poetic thoughts…andrew

apologies for the many typos in the last post — working on an unfamiliar machine – andrew