Nassim Taleb is a very bright guy. He has some strange social and communication skills (he savagely ridicules those he thinks exemplify foolish qualities, he’s annoyingly arrogant, and he comes across as a bit scatterbrained both in TV interviews and in some of his writing). Because of this, it’s a bit surprising that his work (The Black Swan, Fooled by Randomness) has become so popular. But, given that he “predicted” the financial crisis, and made a lot of money by betting on it (or, more accurately, betting against it not occurring), he’s recently become a celebrity and is being treated as a business guru (he was very visible at Davos this year, where the charts above and below were presented). His books present some interesting, and truly original, thinking. One of my current work projects is to get business leaders to think of environmental sustainability as congruent in the long term with business sustainability, and to think of both in the context of risk management. I recently presented a paper on this subject that I co-authored, in London at a Prince’s Trust event on sustainability. It argues that the risk management models currently used in business need to be enhanced to consider:

Taleb’s key argument fits well with the above ideas. His thesis for the book is: We favor the visible, the embedded, the personal, the narrated, and the tangible; we scorn the abstract. Everything good (e.g. aesthetics, ethics) and wrong (e.g. being fooled by randomness) with us seems to flow from this.

We are wired, he argues, to deal with immediate emergencies (fight or flight, when being pursued by predators), and to optimize the likelihood of procreation. Because of this, our brains, emotions and instincts can be “fooled”. Several of these types of foolishness are now getting our species into deep trouble:

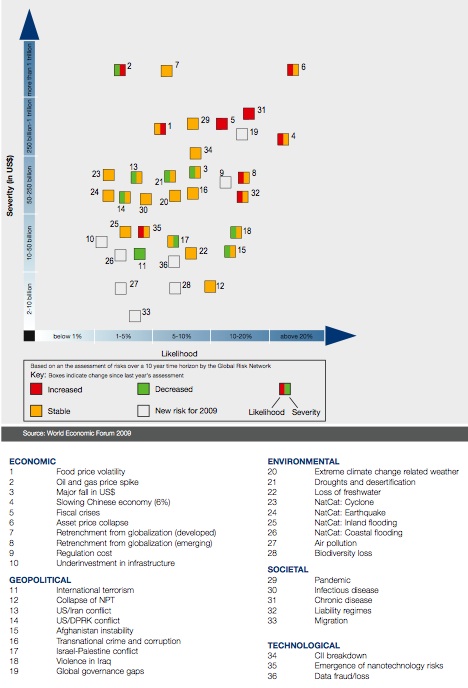

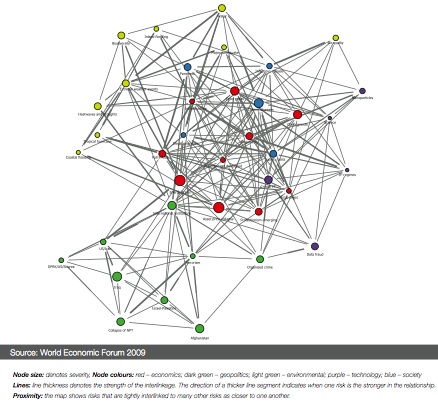

Because of these biases, we are, he argues, very poor at assessing risks (both their likelihood and severity). I would say (as someone who has struggled with large organizations that have a strong, unacknowledged bias against true innovation) we are equally poor at assessing opportunities (both their likelihood of success and their consequences if they do succeed), because of these same biases. So, looking at the risks in the top chart above, Taleb would probably say that (1) we are probably underestimating the consequences of many of the risks on the left (low perceived likelihood) side of this chart, (2) we are missing a raft of risks on this left side that we have forgotten can occur or can’t even imagine occurring, and (3) the combined probability of at least one (and probably several, possibly interdependent) of these ‘individually low-likelihood’ risks occurring is very high, and that occurrence, far more than the higher-probability “known” risks on the right side of the chart, is what we should really be considering, and preparing for. This is at least easier when we know what those risks are. We can anticipate the consequences of another disastrous war, next time in Iran or North Korea (and Obama’s decision to escalate the war in Afghanistan today signals that he is also incapable of learning the lessons of history, which is an ominous sign). We know, from the sad lesson of Katrina, that the consequence of natural catastrophes in the 21st century will be to abandon afflicted cities to die (we simply cannot afford to rebuild them), just as we abandon old buildings and factories. From the 1970s and 2008, we have an inkling of the consequence of huge oil price spikes (though the gnomes of Davos still cannot get themselves to acknowledge that the real risk is not a price spike, but the end of oil as the engine of our economy). From the great blackouts we’ve experienced, we’re reluctantly aware that the decaying and neglected infrastructure in our cities everywhere is going to cause us enormous problems, but because we consider it (for now) a low-likelihood catastrophe (and because we can’t afford to fix it) we just put it out of our minds. Same thing with pandemics and water crises: we know they’re coming, and that they will both cause a horrific economic downturn (and the indirect economic consequences will probably kill more people than the diseases and droughts will kill directly), but because they’re still ‘unlikely’ in any year (and hence ‘unlikely’ to occur in the 10-year horizon of the charts above), we do nothing. Another real problem is all the risks that are not even on the chart. What if the real political crisis is not war in Iran, but the collapse of Mexico? There are plenty of warning signs for this, but we haven’t even begun to consider what happens when organized crime takes over an anarchic state right beside us, and fifty million people seek asylum elsewhere. What if the real terrorism risk in not an ‘international’ threat but a bunch of whacked-out individuals who manage to produce (not as hard as you might think) weaponized anthrax and use it as a carrier for smallpox? What about a good old fashioned nuclear war between India and Pakistan? I can imagine dozens of risks, some of which have a long history of occurring but not recently (think Mao and ask why a populist coup in China is not on the risk list above), that belong in the upper left corner of this chart. They are all perhaps ‘unlikely’, but taken together, their probability is as high as the probability of an attack on the US was a year before 9/11, and their consequence is likely to be much greater. My pick for ‘breakout’ risk of the year? Food crisis (notice they call it “food price volatility”: the gnomes can’t quite get themselves to use the real ‘f’ word famine). It’s in the upper left (#1) but there’s lots of evidence it should be in the upper right. Unless they’ve read something about history, people think famine is something that only happens in Africa and Asia. But then, last year the gnomes only gave “asset price collapse” (their euphamism for global depression) a 20% chance of occurring in the next decade, and still don’t think that it’s much more likely than that. Another weakness in our analysis of risks is that we tend to view them all as temporary ‘events’ that need to be mitigated and survived, until things “return to normal”. But just as some innovations (what Christensen and Raynor call “disruptive innovations”) permanently change the business landscape, some risks (climate change, the end of oil) will, when they occur, usher in permanent structural changes in our world and in our economic and political systems. That’s something Taleb doesn’t deal with, but which I hope to continue to write about. The real value of scenario planning, simulations and other adaptation risk response strategies is not so much that they help us anticipate system shocks (though they can do that), as that they help us prepare for permanent shifts in our world, and help us learn to cope with complexity. PS: Taleb’s advice is to shun the mainstream media, avoid self-help books and advice that would presume to make us who we are not, never complain (it’s no one’s “fault” so there is no point), never take compliments or harsh criticism too seriously (they say more about the speaker than about you), avoid superstition, never gamble, always be skeptical of apparent causality, and try to avoid path-dependent decisions (those you make unaware of your anchoring bias, described above). He also suggests not scheduling your life tightly, since he’s observed that “time optimizers” are generally more unhappy because they set up more opportunities for “failure”. I actually find his advice (despite his warning against taking advice from anyone) more interesting than a lot of his explanation of how we are fooled by (im)probabilities. Category: Complexity

|

So much for getting and staying really organised, and over-planning. I like your PS, it fits nicely with the way I approach life, more or less.

“In an increasingly complex world our minds crave simplification”. I find this to be more true the older I get. I want simple clear cut directions. If I buy something I have to put together I’d much rather have a youtube video to demonstrate it. I was spoiled by the simplicity of using a mac computer for a long time. There is an increasing reluctance to want to learn new simple little things (“new” as in new to me). I’m not sure if this is a result of getting older or a result of having been more and more spoon fed with nice bullet point instructions, power point presentations, videos etc. In the past I was often intrigued by things that were complex and would be curious about figuring it out. Now I lose patience if they don’t present it all to me in refined, easy to digest, spoonfuls of pablum. And about the risk of famine: I’d be interested to know a way to figure out how many days of food a particular town or city has before it will run out. I know our shelves get emptied quickly when there are a lot of tourists around. I wonder how many days of food we would have if the trucks stopped moving. Not sure how to figure out something like that or who to ask. Very interesting blog post today. Thanks.

Ah, by using hindsight I have spotted a precursor to the ‘Black Swan’ which took the form of some advice given on the mainstream media by a ‘lucky’ author. He presented it in a simplified narrative which could be extrapolated into all areas of life.William Goldman; “Nobody knows anything”.

I find this world view refreshing. “never complain (it’s no one’s “fault” so there is no point)” Yes, it is no one’s fault. It reminds me that we should be very cautious, maybe even afraid of what we think. The bumper sticker “Don’t believe everything you think” is so true. I can see how one false assumption has lead us down the wrong path of more and more wrong assumptions time and time again. Life is vary random and we error in thinking otherwise. Biologically we crave order. And here in lies the struggle.

Excellent post! I believe the thoughts formulated here, be they from Taleb’s or Dave’s writing feather, are the exact kind of thinking that is so lacking and so necessary in the brains of decision makers in politics and business all over the world.To get it into those guys’ brains, the only way possible I can imagine is to use some sort of propaganda which pretends to these decision makers that it is actually the only way to enrich their personal lives, therefore feeding their (usually very hungry) greed – those who have read Asimov’s Foundation might understand better what I mean. Otherwise I apologise for not being more detailed.Short and sweet, I guess it is ironically necessary to use weapons of mass delusion to get the RIGHT kind of message across, rather than the wrong one. Now, how dangerous is that? And who knows a “better” way?

Hi, what a wonderful post and paper – it is incredibly difficult to understand risk (especially many financial services professionals in the past 20+ years) and culturally in financial services – managing personal exposure to risk as well as the risk they are attempting to manage for their clients (if that makes sense).I like Taleb too. I haven’t had a chance to read his book but have visited his website, seen interviews / discussions with him – I really liked recently when he mentioned about now being able to bankrupt a bank by Blackberry – scary and true, also his thoughts about if you want advice, take it from cab drivers :-)I don’t understand all the financial side of it quite yet, I have some concern about computer / information technology being used to interpret risk but as you mentioned in your paper – about needing research to enhance the ERM model “to incorporate (i)compliance and governance risks in areas where risk management responsibility cannot be readilyassigned and where risk management and complexity management competency may be lacking,”This might be incredibly stupid but can only speak from where I’m at – it appears that a lot of people involved in investment are talking about investing in environmental technologies and infrastructure – the new big thing to invest in – however as I understand it, to take advantage of those kind of investment opportunities would take a considerable amount of wealth in the first place ? So oil sultans become renewable energy sultans ? So nothing changes – or am I missing something ?

So mister Taleb is not talented, he was just lucky to hedge against crisis at the right place, at the right time, isn’t it?Besides, who is ‘we’?CEO and politicians? I mean greedy people…because we, scientist, are no fool, and we know for sure a catastrophic climate can, and did, occur in a few decades. And please don’t forget the bright american scientists who predicted Katrina’s type of flooding on New Orleans, but who were ignored by “decision makers”! (I mean the dishonest, lyars that grab the social ladder by stepping over anyone else life)

Thanks for the intro to Taleb’s work. Gonna dig around in it a bit.

Interesting. He missed out on at least two… we are also, perhaps paradoxically, intoxicated, fooled and unbalanced by too much abstraction… and the whole thing reeks of managerial bias, the assumption that we can manage our way out of our predicaments if only we see them coming. I don’t think so anymore, and I see much of the panic-mongering out there as a way to scare us and manipulate us, rather than to accomplish something useful.Food? I heard we have three days in the stores, and two weeks area-wise (counting what’s in the regional warehouses).

So if black swans are unlikely but potentially catastrophic events, what do we call the unlikely but potentially wonderful events? I’m all about the blinding surprises of positivity. Taleb can have his black swans. I want to be an expert on white ducklings. :)

That list of biases fits very well with my experience and agenda too … the “reason” behind so much poor organizational decision-making. Thanks for that reference Dave.