| Growth is unsustainable. Period. A lot of (even progressive) economists still don’t seem to get this. “Of course the recession will end soon, and we’ll be back to ‘healthy’ growth again,” they say. The only debate seems to be when it will end and how bad it will get before it does.

Two other things economists don’t seem to get:

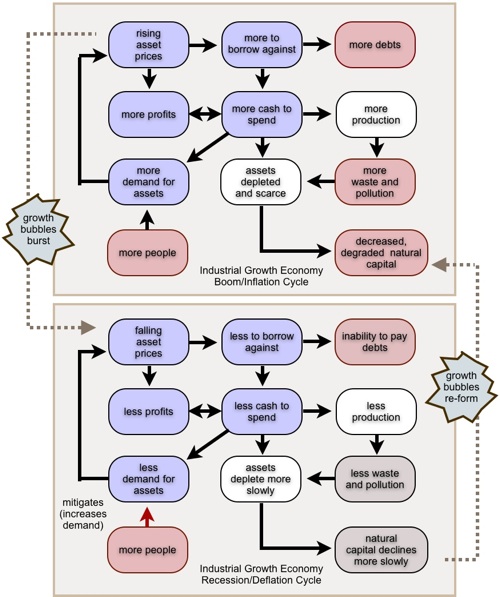

In ‘boom’ times, as shown in the top chart below, prices are inflationary. Don’t let the lies of our governments fool you — compare the cost of housing, cars, health, recreation, education, or the real cost of food (taking into account massive agricultural subsidies) or manufactured goods (taking into account the shoddiness and replacement cost of the crap on the shelves today) to that in 1970 and you’ll see we’ve been in an inflationary spiral for decades. Inflation artificially drives up the price of our homes and investments, giving us more collateral to borrow against, and more cash to spend on these assets, driving the prices up further in a vicious “bubble” cycle (shown in blue). These bubbles produce great profits for corporations (giving us even more ‘valuable’ investments to borrow even more against). They also produce an addiction to debt (for most of us, total assets have doubled in the last forty years, but that increase has been totally financed by debt — net worth hasn’t changed at all, so the ‘wealth’ is all illusory). By producing phony statistics that deny the inflation in this cycle, governments keep interest rates low, so we can afford to borrow even more. The result: spiralling debt, more waste and pollution, and a rapid decline and degradation of our finite, fragile natural capital. As Daniel Quinn has explained, the glut of cheap subsidized food also produces the population boom that has been going on for centuries, further exacerbating the cycle. The bubbles are, of course, unsustainable, and when they burst you get a different, but nearly as devastating, vicious cycle shown in the lower diagram above. Asset prices plummet, we have less to borrow against and less cash to spend, so the demand for assets falls further and you have a deflationary spiral (the vicious cycle in blue) — talk to anyone in Japan if you think that’s any better than an inflationary spiral. If you have an ongoing population explosion (like that in North America caused by high immigration), that will mitigate this cycle somewhat, driving up demand and restarting the bubbles. During this recession/deflation cycle, there is less waste and pollution, and less decline in our natural capital, but not by much. It merely decelerates. And for the poor, unable to pay the debts they incurred when their collateral was ‘worth’ much more, the impact is devastating — foreclosure, bankruptcy, and in many nations, starvation. This is the boom-and-bust Industrial Growth Economy that has prevailed and become global over the past two centuries. Its consequences are massive waste and pollution (and soon disastrous climate change), excessive population growth (and resultant resource wars), horrific levels of indebtedness and poverty (as inequity of wealth soars), and addiction to consumption. It is utterly unsustainable — the booms and busts don’t cancel out the excesses, but merely perpetuate them. Because of these vicious cycles and their consequences, we can never ‘afford’ to deal with the unsustainable problems inherent in the Industrial Growth Economy — especially climate change. [The word ‘afford’ means ‘to go forward’, and when you’re caught in a vicious cycle there is no ‘forward’]. In boom times, greater production and greater population produce more greenhouse gases. In bust times, there’s no money to spend on ‘niceties’ like pollution control to reduce greenhouse gases (and in fact in recessions we use cheaper, dirtier energy, and buy cheaper crap that ends up quickly in landfills and incinerators). So these ‘externalities’ (waste, pollution, loss of natural capital) always mount, and politicians and corporations do their best to get the public to ignore them, since they have no solution for them. They’re not accounted for in our measure of profit, wealth or ‘net worth’. The only way out is to abandon the Industrial Growth Economy and shift to a Steady State Economy. As the chart below describes, such a shift requires three interventions (shown in square boxes) to bring it about:

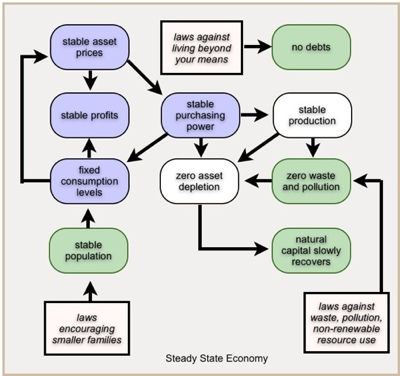

These interventions could eliminate debt-driven inflation and consumption, waste and pollution, population growth and the degradation and loss of natural capital. Instead of the Industrial Growth Economy’s vicious cycles we would have a virtuous cycle of stability in prices, purchasing and consumption: Many ecological economists have written about this (notably Herman Daly, Richard Douthwaite and Peter Brown). Prior to modern civilization’s invention of industrial, agricultural, health and financial technologies we lived in such an economy, without the need for the three interventions (nature intervened, when necessary to restore the balance). The problem is that now, we can’t get there from here. Suppose we were to introduce these three interventions, globally. Here’s what would happen:

What I’m saying is that these three interventions fly in the face of human nature, and cannot be effectively implemented. We will inevitably fall back into the Industrial Growth Economy, which evolved as a result of human nature and a response to human needs. It reflects (alas rather sadly) who we are as a species. There is no going back to the garden once your species has tasted the forbidden fruit, and we’ve absolutely gorged on it. It’s only natural. This is why all civilizations crash as a consequence of their excesses. This is why the ecologist-philosophers who are also students of human nature (John Gray, Ronald Wright, and I suppose Dave Pollard) see the catastrophic collapse of our now massive and global civilization as inevitable. It is not in our nature to live within our means, to limit our numbers voluntarily, or to conserve for future generations (especially when we don’t appear to have enough to go around for our current numbers). The way we are, and always have been, we cannot ‘afford’ to combat climate change. Even though the cost of not doing so is extinction. Category: Why Our Civilization is Unsustainable

|

Dave, thanks for throwing a huge stinking wrench in to what was up to now a very good day for me :)

an excellent piece again!while it is true that there is no going back to the garden once you’ve gorged on the forbidden fruit, one can take solace in knowing that the garden is ubiquitous and responsive. evolution will produce a more disciplined replacement from the sparkles in the sand.

When you say “human nature” and “The way we are, and always have been,” I think you are speaking of what Daniel Quinn describes as the civilized “we”, the “Takers”, who seem to have forgotten the earlier 3 million years of human life. As you point out in a recent post, if we could imagine that we belong to the land (not vice versa), as we did before civilization, we would probably “live within our means” and avoid disaster. But what a change in story that would be! Not likely.That leaves me wondering: What are the most useful questions we can ask now? We have already asked and (largely) answered questions about ecology, history, politics, economics, the nature and limits of civilization. The answers (shared in this blog and elsewhere) have been shocking and frightening, and should have destroyed the myths of progress and control by now–though I’m afraid many readers are still clinging to one or both of those myths. So what are our next questions?One that I am thinking of: “While the world as we have understood it falls apart, how can I guide myself and others through the confusion and pain?”

Dave, reading your piece my thoughts turn to the backward bending labour supply curve.Definition:graph illustrating the thesis that as wages increase, people will substitute leisure for working. Eventually wages can get so high that if they increase, less labor will be offered in the market.Back in the 1800s England, people would show up to work, earn enough to buy what they needed and went home, much to the disdain of the factory owner.THIS is human nature!To keep workers coming back many ruses have been designed and put in place, one of them making everything in short supply so workers have to keep coming back. The other is monetizing everything, so only wages solve life’s needs.So maybe it is not just the size of the wages, but also the lack of return on investment of going to work.(If there were NO return, and you still had to do it you would be a slave. No US citizen would accept wage slavery as a future option.)My hope is to human beings’ laziness. When there is no point in going to work (Since 1970’s US citizens are working 20% more for No increase in wages) maybe people will relax, enjoy simple pleasures, organize themselves locally. Let’s face it, the economical advantages of showing up at work at getting smaller and smaller. Rational man might just take off and …. relax.

Humans have survived massive climate changes before. Why do you think we will not survive this one?

Why is less people the solution? Even if it is the solution we know how to cut down on population growth, just make people richer and they stop having more then 2 children per couple.

“It is not in our nature to live within our means, to limit our numbers voluntarily, or to conserve for future generations “Thanks it’s a nice reason to hate human beings, hopefully your last sentence predicts, extinction!….When will it be finally time to party?

Where does all this fatalism come from? I think people like to predict the end of the world because it gives them a sort of comfort or determinism. Is GAIA just another humanist reinvention of religion? Is environmental collapse just the apocalypse for atheists? We must convert all the sinners(resource wasters)or the world will end.

Thanks for the comments, everyone. I guess my answer to the skeptics is that my pessimism has grown in concert with my knowledge (as Einstein observed this is not uncommon). And while there’s a short-term correlation between affluence/education in the 20th century and reduced family size, this correlation is novel, and not shown in any sense to be causal (most people, affluent and struggling, still want more children than they eventually have). It’s not just climate change, it’s the cascading series of interdependent crises our excesses have set us up for in this century — overpopulation, end of oil and water, soil exhaustion, universal access to WMD etc. etc.

Dave I’ve had the exact opposite transformation. I bought the overpopulation theory after reading the Population Bomb by Paul Ehrlich but after forty years none of his predictions came true so eventually you have to re-examine the premise. Thomas Malthus was the first to use math to predict that overpopulation was going to lead to food shortages and that was 2 centuries ago can we at least agree he was wrong?Hans Rosling has the best summary of the actual state of the world using UN statistics I highly recommend it. http://www.ted.com/index.php/talks/hans_rosling_shows_the_best_stats_you_ve_ever_seen.html