When the Internet was first starting to catch on in the 1980s, I was invited, as a representative of a large business consulting organization, to a day-long seminar explaining what this new phenomenon was and how businesses should be responding to it. It was led by a man who now makes millions as a social media guru (I won’t embarrass him by identifying him), but at the time he warned that the Internet had no future. The reason, he said, was that it was “anarchic” — there was no management, no control, no way of fixing things quickly if they got “out of hand”. The solution, he said, was for business and government leaders to get together and create an orderly alternative — “Internet 2” he called it — that would replace the existing Internet when it inevitably imploded. Of course, he couldn’t have been more wrong.

The Internet represents a different way of ‘organizing’ (though that word doesn’t quite fit) a huge system. Instead of a hierarchy, it is what Jon Husband has coined a “wirearchy” — a vast network of egalitarian networks. It follows nature’s model of self-organizing, self-adapting, evolving complex systems, instead of the traditional business and government top-down, controlled, tightly managed, complicated system model. There have been many attempts to graft a hybrid of the two, but they have never worked because complex and complicated systems are fundamentally and irreconcilably different.

It is because business and government systems are wedded to the orthodoxy of hierarchy that as they become larger and larger (which such systems tend to do) they become more and more dysfunctional. Simply put, complicated hierarchical systems don’t scale. That is why we have runaway bureaucracy, governments that everyone hates, and the massive, bloated and inept Department of Homeland Security.

But, you say, what about “economies of scale”? Why are we constantly merging municipalities and countries and corporations together into larger and ever-more-efficient megaliths? Why is the mantra of business “bigger is better”?

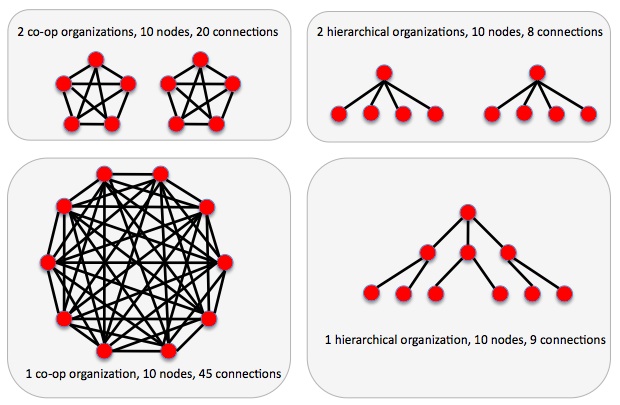

The simple answer is that there are no economies of scale. In fact, there are inherent diseconomies of scale in complicated systems. When you double the number of nodes (people, departments, companies, locations or whatever) in a complicated system you quadruple the number of connections between them that have to be managed. And each “connection” between people in an organization has a number of ‘costly’ attributes: information exchange (“know-what”), training (“know-how”), relationships (“know-who”), collaboration/coordination, and decision-making. That is why large corporations have to establish command-and-control structures that discourage or prohibit connection between people working at the same level of the hierarchy, and between people working in different departments.

Why do we continue to believe such economies of scale exist? The illustration above shows what appears to happen when an organization becomes a hierarchy. In the top drawing, two 5-person organizations with 10 people between them have a total of 20 connections between them. But if they go hierarchical, the total number of connections to be ‘managed’ drops from 20 to 8. Similarly, a 10-person co-op has a total of 45 connections to ‘manage’, but if it goes hierarchical, this number drops to just 9.

This is clearly ‘efficient’, but it is highly ineffective. The drop in connections means less exchange of useful information peer-to-peer and cross-department, less peer and cross-functional learning, less knowledge of who does what well, less trust, less collaboration, less informed decision-making, less creative improvisation, and, as the number of layers in the hierarchy increases, more chance of communication errors and gaps.

Nevertheless, this is considered a fair and necessary trade-off. The 10-person co-op organization in this illustration is already starting to look unwieldy, so imagine what it would look like with 100 people (thousands of connections) or 10,000 people (millions of connections). By contrast, the hierarchical organization that combines 2 five-person companies only increases its number of connections from 8 to 9 (and perhaps even fewer if some ‘redundant’ employees are let go after consolidation). With similar control spans a hierarchical organization of 100 or 10,000 people only needs an average of one or two connections per employee, a fraction of what the non-hierarchical organization would seem to need. Isn’t this apparent efficiency advantage a worthwhile ‘economy of scale’?

It isn’t, and for the same reasons noted above: as the hierarchy gets larger, the loss in exchange of useful information peer-to-peer and cross-department, the loss in peer and cross-functional learning, the loss of knowledge of who does what well, the loss of trust, the loss of capacity for collaboration, improvisation and innovation, the inability to make informed decisions, and the volume of communication errors and gaps increases exponentially. Beyond about 50 people, the hierarchy begins to get dysfunctional, and much above that (as in most large corporations, government departments, agencies and other organizations) it becomes totally dysfunctional and sclerotic — incapable of change or innovation.

Why do these large organizations seem to be so effective then, at least in the private sector and when measured by market dominance and profitability? There are a number of reasons:

- As they get larger, their political power rises proportionally, so they can effectively lobby governments worldwide for subsidies, legal protections, preferential treatment, and tax and regulatory changes that give them a huge competitive advantage.

- As they get larger, they qualify for large volume discounts from suppliers.

- As they get larger, their power in negotiating with unions and employees grows — they can always threaten to hire new, cheaper employees, contract out, outsource or offshore work (and usually do so)

- As they get larger, their market presence gets larger, so they don’t have to work so hard to attract new customers or experienced employees

- As they get larger, they can afford to buy up, intimidate and crush smaller innovative competitors, and by eliminating competition easily increase market share and reduce downward pressure on product prices.

So these so-called “economies of scale” have absolutely nothing to do with efficiency or effectiveness and everything to do with abuse of power. These abuses of power are all “win-lose” — and the losers are taxpayers, ripped-off customers, domestic and third-world citizens and workers, innovation, so-called ‘free’ markets, and our massively-degraded natural environment (which they shrug off as “externalized costs”).

In the public sector, the loss of connection as governments, agencies and other organizations grow ever-larger are similar to those in private organizations, but because their mandate isn’t revenue and profit, but public service, the diseconomies of scale are somewhat different:

- less personal knowledge of ‘customers’ means reduced ability to be of real, customized service, and less awareness of the consequences of poor service

- less exchange of useful information peer-to-peer and cross-department means the one hand doesn’t know what the other is doing, resulting in bureaucracy, redundancy and runarounds for ‘customers’

- less peer and cross-functional learning and less knowledge of who does what well means lower levels of competency and less recognition of excellence by peers (often its own reward)

- less trust means less willingness to offer ideas to innovate or improve processes and services (why take the risk?)

- less collaboration means more workarounds, more unprofessional make-it-up-in-the-moment answers to systemic problems and needs

- less informed decision-making means top ‘officials’ in these organizations often make incompetent decisions and rules, forcing employees to find convoluted workarounds to do their jobs without contravening higher-up decisions

- more communication errors and gaps mean costly service mistakes, insufferable delays and inconsistent service

- governments and agencies then try to offset the economic diseconomies of scale by forcing each employee to do more and more work, resulting in burnout, inattention and exhaustion

- consequently bright minds are often enticed to work for private corporations instead of in the public service because it seems less frustrating and pays more

To be sure, these size-diseconomies are also present in large private organizations, and in fact, John Ralston Saul in The Unconscious Civilization provides compelling evidence that large governments, agencies and public sector organizations are significantly more effective at providing value to citizens and ‘customers’ than comparable-sized private organizations (not that that’s saying much). So as much as we love to loathe governments and their agencies, privatization almost always makes things worse.

Just as the larger a private corporation becomes the more dysfunctional it gets, the more people a government serves and the farther its representatives get from citizens, the more dysfunctional it becomes.

So why do we (including many liberals) so often want to centralize government services and administrations in the search for economies and effectiveness? The answer in part is that we want to believe that combining functions could eliminate unnecessary duplication and allow the introduction of so-called ‘best practices’ across a wider jurisdiction. When we see two public works departments doing the same thing in adjacent communities with no coordination of effort, the wisdom of combining them would seem a no-brainer. But unfortunately the effect, as noted above, is usually the opposite. We confuse ‘efficiency’ and ‘effectiveness’, and are often drawn to centralization that would seem to offer at least short-term ‘efficiency’ gains, and then get distressed when the result, at least in the longer run, is the opposite. The citizens of many municipalities that have chosen to amalgamate often deeply regret these decisions and try (usually in vain) to reverse them. Likewise, consolidating and combining government departments tends to increase, not decrease, bureaucracy.

Likewise, most business ‘combinations’, mergers and takeovers actually produce ‘negative shareholder value’ (i.e. the value of the merged organization is less, five years hence, than the value of the predecessor organizations). And except for the people at the top of the hierarchy (who end up with more power and bigger bonuses), such combinations almost always disappoint employees of both predecessor organizations (even those who have kept their jobs, who often end up with more responsibility with no more pay). Sales and profits are up, but except for top executives and major shareholders, everyone is a loser.

So back to the purpose of this post, to answer these questions: 1. What is it about the ‘organization’ of the Internet that has allowed it to thrive despite its massive size and lack of hierarchy? And: 2. What if we allowed everything to be run as a ‘wirearchy’?

To answer the first question, the Internet is a “world of ends“, where the important things happen at the edges — and everything is an edge. “The Internet isn’t a thing, it’s an agreement”. And that agreement is constantly being renegotiated peer-to-peer along the edges. If you look at the diagram above of the co-op with the 45 connections, you’ll notice that the nodes are all at the circumference — around the edges. There is no ‘centre’, no ‘top’. And the reason the organization isn’t weighed down by all those connections is that they’re self-managed, not hierarchically managed. The work of identifying which relationships and connections to build and grow and maintain is dispersed to the nodes themselves — and they’re the ones who know which ones to focus on. That’s why the Internet can be so massive, and get infinitely larger, without falling apart. No one is in control; no one needs to hold it together. It’s a model of complexity. And, like nature, like an ecosystem, it is much more resilient than a complicated system, more effective, and boundary-less. And, like nature, that resilience and effectiveness comes at a price — it is less ‘efficient’ than a complicated system, full of redundancy and evolution and failure and learning. But that’s exactly why it works.

THE NATURAL ENTERPRISE MODEL (from my book Finding the Sweet Spot)

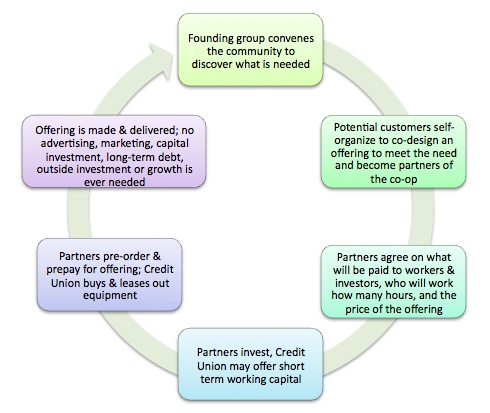

Turning to the second question, let’s start with the private sector: What if all businesses operated as wirearchies? Let’s picture what that would look like:

- No hierarchy — everyone is an equal and trusted partner, with equal capacity to make decisions and to make contracts

- Self-organization and self-management — collective, collaborative, consensus-based decision-making, including decisions on membership, roles, remuneration, objectives, and strategies

- Autonomy — each individual is authorized to make decisions, without fear of repercussions, in specified areas of responsibility; each self-selected ‘business unit’ is similarly authorized in other areas of responsibility, deciding by consensus; a few defined decisions are made by a central directorate with rotating membership responsible to the whole

- Small is beautiful — once the business reaches a certain size at which diseconomies of scale start to arise (say, 150 FTE members), it is split into two or more fully-autonomous units

- Shared values and principles — each business agrees to follow and operate in a manner consistent with a set of overarching values and principles, some of which are specific to the business or the community in which it operated, and others of which are international standards, conditions of operation anywhere (see for example the values and principles by which co-ops around the world operate)

- Network of networks — rather than competing, each business collaborates in a network with other businesses to collectively solve ‘customer’ needs

Such ‘tribal’ organization is how humans first came together to achieve common goals. Notice that this ‘picture’ is only peripherally about the business of an entity (in fact the entity tends to be almost entirely transparent). This is a picture of an agreement, a negotiation — very much the way the Internet is.

This is how many co-operatives operate now (and there are millions of them). It’s a deliberately democratic, non-hierarchical means of self-organization. Suppose we could evolve a system where every business operated this way. They would not pursue profit, only sustainable solvency. They would exist to be of use. They would have no absentee owners or debts to outsiders, other than short-term working capital loans from credit unions (which are another form of co-op). Their members would all live in the community in which they operated. They would have no need to spend money on advertising, marketing, PR or other zero-value-add activities. They would need no ‘venture’ capital. They would operate as peer-to-peer organizations using peer production methods.

By virtue of their (self-)organization, structure, principles, modus operandi and size limits, they would be subject to none of the diseconomies of scale noted above. And with limited power they would also avoid the pathology that is so endemic in large global corporations today. They would be inherently more (socially and ecologically) responsible and sustainable than today’s corporations, and more joyful places to work. They would be more responsive to local needs. There would no longer be any such things as ‘jobs’, ’employment’ and ‘unemployment’.

In short, they would run like the Internet — no one in control, agile and self-adapting to changing ‘user’ needs and circumstances, evolutionary, collectively massive but not dysfunctional, participatory, democratic, open to all, and politically neutral.

The struggles of the Occupy movement, and other social and economic justice movements, have made it clear we lack the political will to dismantle the existing corporation structure and strip corporations of the subsidies, perks and power that they now enjoy (and utterly depend on). But that doesn’t mean a wirearchical economy couldn’t be established and thrive, the same way the Internet did and has, and then, when the current economic system inevitably collapses, wirearchy might fully supplant hierarchy in the private sector.

The biggest challenge in creating this New Economy is that the core skills needed to create millions of co-operative enterprises (ones that fill identified, unmet real human needs) are in short supply, are not taught in the ‘education’ system, and are more advanced than the skills we had to develop to use the technology of the Internet. But it’s possible, and the New Economy movement is clearly growing, and will start to provide these skills and hence support wirearchies as it gains momentum.

So if it could work in private sector, what about the public sector — could governments, agencies, not-for-profits and other public organizations work as wirearchies?

Here’s a list of the major services that such organizations currently provide: Health and wellness, education, ‘public’ roads and transportation (including ports and airports), mail, police/fire/emergency/security services, conservation, sport and recreation, water and waste management, arts and culture, ‘public’ utilities, social and spiritual services, defence, old age security, unemployment and occupational accident insurance, ‘public’ auto insurance, regulation, ‘public’ broadcasting, lotteries, management and governance, international aid, legal aid, lobbying, collective buying, co-operative and ‘public’ housing, and political and social activism.

Together, they make up about half of our economy, according to some estimates. Some are large and bureaucratic, some are small and bureaucratic, some are small and lean. Some are centralized, some are dispersed, and some are small, single-location organizations.

What is they all were operated like the Internet? Some of these services are already offered by volunteer or not-for-profit organizations, but in many cases these emulate the hierarchical structure and other dysfunctions of the private sector. (The only thing worse than working for a tyrannical and incompetent boss is working for one as a volunteer.) And many of these services are offered by government bureaucracies that exhibit the worst, entrenched dysfunctional behaviour and power politics.

But just as for the private sector, we need not wait for the established hierarchical public organizations to collapse before we start to create co-operative wirearchies that fulfil these functions. And they would have the same 6 characteristics: no hierarchy, self-organization and self-management, autonomous, small and size-limited, adhering to a shared and universal set of values and principles, and network of networks.

So the short answer to the question: What if everything ran like the Internet? is a bit of a mixed bag:

- A significant portion of our economic and social activity already does run (at least in part) this way

- It would potentially eliminate the current diseconomies of scale and power abuses that plague our current hierarchical systems, and it would be more sustainable, more responsible and responsive to citizens, and more joyful and fulfilling

- The transition to get there would be furiously resisted by those running current hierarchical organizations, and would run up against great skepticism from citizens who think the current hierarchical systems are the only viable ones

- There’s a huge learning curve to get there, but we have time (and we’d be better off learning now than waiting until the hierarchical systems collapse and making our learning mistakes then)

- Everything would be much more local, hands-on and personal, for better and for worse

The first steps towards getting there, I think, are learning steps:

- Learning about co-operatives and their formation and operation (and identifying some of the things co-ops often currently do wrong, such as allowing themselves to grow too large, so that we can make them truly wirearchical)

- Learning about what is needed in the world that hierarchical organizations aren’t currently or properly providing that wirearchical ones could

- Learning about what we have to offer the world (our gifts and our passions) personally and collectively

- Learning consensus, conflict resolution, negotiation, collaboration skills, listening skills, self-organization, self-management and the other critical competencies needed to make wirearchies work

- Discovering who the potential partners in our community are — acquiring the “know-who” of what others do and know, that complements our own “know-what” and “know-how”, and learning how to partner (a skill few possess, one that is about collectively negotiating shared power and increasing autonomy, that would be useful in all aspects of our lives)

I’m thinking about how I so much wanted my book to be a vehicle for this learning, and how no book alone can hope to be that. And I’m thinking about what I can do, now, to be of use, to help evolve something that can.

“The simple answer is that there are no economies of scale.”

I think most of us have personal experience of economies of scale that have effectiveness as well as efficiency.

A little less simplistic answer is that economies of scale have, like most things, points of diminishing returns (in terms of both efficiency and effectiveness) that depend on context. Theory is useless without practice and measurement.

Stigmergic or self-organizing complex systems are common in biology and they occur in human behavior as well but people aren’t exactly ants or fish. We can’t rely on thermodymanics or stigmergy alone to shape society.

I just read this morning “The Tyranny of Structurelessness” http://www.jofreeman.com/joreen/tyranny.htm

Pingback: O pecado das organizações públicas hierarquizadas

Very nice post, David. It explains a lot of my felt experience working at a large corporation, and how it seemed to get less functional as it became larger. I assume you are familiar with Geoffrey West’s work, which contrasts the growth of cities (which are very Internet-like in their connections) to the growth of corporations (which, well, are not).

http://longnow.org/seminars/02011/jul/25/why-cities-keep-growing-corporations-always-die-and-life-gets-faster/

What an incredible vision full of so many possibilities. Many great points. I think what I hear you saying on one level, is that there may be an optimon size in human terms and also in terms of efficiencies of scale. It is a big picture, Dave, and not so easy for the average idiot like me to wrap my mind around. I do like the star topology, though. Not sure of an optimon size, but that certainly stands to reason. You do not have 22 players on a baseball team, that is just too many. Nature does define size but man does what he wants. The optimon size for a dog is about 25 pounds left to its’ own devices. What will make humans choose quality and effectiveness over the advantages of working for a big company where responsibility can be easily deferred and there is no direct contact with the irksome customer? It is about people as a whole choosing to be decent, isn’t it? During WWII when fubar and snafu were rules of the day, people still made it work, because they wanted to. If people were similarly motivated, I am sure a way would be found. I tend to agree with poor richard that structure is essential. We asked in the sixties, or rather Robert Crumb asked,”Is this a system?” And the answer is, there always is a system, whatever it is and it only matters if the people chose to act as human beings and not to let the system turn them into automatons.

“the computer won’t let me do that” is the ultimate perversion of machine over sentient human sensibility. What is the optimon size for a committee?

Bart: The optimal size of groups: http://howtosavetheworld.ca/2009/03/18/the-optimal-size-of-groups/

I don’t think it’s about choosing to be decent; I’m not sure we would have evolved so successfully if that were a criterion. We do what we do because of love — the love of doing things we’re passionate about (fortunately different for each of us), things we’re uniquely good at, things that others clearly appreciate and which fill real needs, things that are fun. It’s joy, not work, and as long as we’re in a small network (even if it’s part of a larger network) we can have it all, as hard as that possibility is to see from where we are now. The Internet shows that networks of networks are possible, that they scale in ways hierarchies never can.

Pingback: What If Everything Ran Like the Internet? « Chris Corrigan

I’m hoping the tide is turning in the direction of getting there already with small scale independent organisations/individuals getting things done through collaboration.

Dan Pink describes this well in Free Agent nation, which holds truths for the UK as well as the US.

Here in the UK the rise in percentage growth in start ups of Social Enterprises compared to other new business is another interesting and optimistic sign in the UK of a return to ventures motivated by shared values.

Pingback: What If Everything Ran Like the Internet? | Pap...

While I agree with a lot of your description of organizational complexity, I am less enthusiastic about cooperative models being the best way to solve the problem. I have two issues with your (and the general) coop vision:

1.) Nature is not devoid of hierarchy, it is not a flat network, on the contrary, all the complexity of nature comes from hierarchies of integrated modular levels with their own hierarchical control systems. Trying to completely flatten organizations is the equal but opposite problem of having too much rigid hierarchy. The trick is to find the criticality points that balance out scale and structure. The problem is not with hierarchy, it is with bloated bureaucratic hierarchies and misaligned management goals.

2.) The funding model of cooperatives, relying on stakeholder issued debt and debt financing from credit unions, cannot compete with equity models of finance and investing, especially if you want these organizations and the economy as a whole to keep innovating. As long as there is risk involved, there needs to be reward that motivates risk taking, and you can’t get that with simple debt structures. An economy dominated by cooperatives is a steady-state equilibrium with zero or negative net growth. Again, nature is not in equilibrium, it is an out of equilibrium process that needs to keep growing. The trick is to control the growth appropriately in the right directions.

As an aside, older posts by you show that your worldview is heavily influenced by the Stephen J. Gould model of evolution and biology, with all the philosophical consequences that come along with it. Gould, though articulate and interesting, was wrong, and so a lot of your inferences about what society ‘ought’ to do which are based on this wrong model of what ‘is’ are misleading.

In fact, the Internet as we know it, is also hierarchical, due to its silos and protocols.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8c0sX6j5D_c

I appreciate this post. I really want to see people get it about what successful networks and co-ops involve. I’m replying here partly to some of Dave’s points and partly to other comments.

No one experienced with co-ops advocates for pure flatness, and the idea that organizations can run without structure is terribly 1960s–fortunately it’s been eclipsed since then by plenty of knowledge of better means.

Complex networks–and real co-ops–don’t look like Dave’s co-op diagrams, they look like more like these examples:

http://groupworksdeck.org/pattern_map

http://colaboratorioartandspace.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/redes-colaboratorio.jpg

http://olimould.files.wordpress.com/2009/01/network-diagram-2.jpg

No member of even a 20-person food co-op maintains equal relationships with all the other members; rather, they organize into various teams & subgroups, and individuals or teams are given authority to manage areas of operation. That mode scales up well, and there are plenty of successful examples to draw on:

(a) Business: 256 companies inside Mondragon in Spain–http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mondragon_Corporation;

(b) Intentional communities: Federation of Egalitarian Communities–http://thefec.org/;

(c) Activism: protesters against the WTO in Seattle in 1999 arranged themselves into affinity groups to take action and participate in spokescouncils–http://beautifultrouble.org/case/battle-in-seattle/ & http://p2pfoundation.net/Spokes_Council_Model.

For a decent overview of multistakeholder co-ops in a business context, see this link: http://www.uwcc.wisc.edu/pdf/multistakeholder%20coop%20manual.pdf.

Pingback: What if Everything Ran Like the Internet? - Consciously Esoteric

Didn’t read the post, the title sounding way too much Rifkinesque charlatinism for me (arithmetic averse, “moral” based principles taken as truth hypothesis on things like energy)

Besides, ever heard of IANA ? IETF ?

The real question is, “Before the internet, why didn’t everything run like the internet?” The simple answer is that outside of ideas themselves nothing in the history of human civilization had a marginal cost of zero until ubiquitous desktop computers came along. Luckily there were some grad students in California during the late 60’s who understood how important it was to ignore costs that wouldn’t exist in the future, and they published standards to make it as easy as possible for potential users to copy whatever they wanted to share with each other. Cut to the internet.

The social media guru you reference was clearly ignorant of this near-unique feature of digital computing, and that’s why he made erroneous assumptions about an emerging system. Unfortunately I think you’re guilty of something like this in the opposite direction: you’re extolling the virtues of a working system that’s predicated on the marginal cost of copying data being zero, and you’re trying to apply its logic to entities which do not share that defining characteristic. Private corporations and centralized governments cannot deliver the overwhelming bulk of their goods and services with a marginal cost of zero. In the areas where they can produce zero-marginal cost goods (i.e., free software) they should do so, probably (but not necessarily) following decentralized development models like the Linux kernel. In the areas where they cannot– like health care and high-end computer hardware– using the internet as a model ignores enormous costs that must be accounted for in any serious critique of their organizational structure.

tldr; you can’t fork water and power

Pingback: Management | Pearltrees

@janciska .. I think you made some good points re: marginal costs of zero not being equally applicable to “other entities that do not share that defining characteristic”. That said, I think I think that the internet and interconnectivity is arguably writing a new equation for many organizations, and their forms / shapes are arguably being altered. But probably not all .. and Dave and I have argued, or discussed different POV’s, about the relative need for hierarchy in increasingly interconnected environments and systems. Underneath *my* thinking about wirearchy is my presumption that there will be many instances of hierarchy in many paces / entities, but that the forms it will take will be increasingly unlike what we tend to think of as traditional hierarchy .. position-based and relatively stable. More temporary, purpose-fitted, handed off sequentially to various people gathered around a purpose based on need and expertise and what needs to get done next, and why .. etc. Dave is interpreting, imagining, what if-ing in this pice .. in my opinion, in a remarkably comprehensive and clearly-articulated way. IMO there will be (many) twists and turns and new discoveries along the way to wherever we are all going .. and interaction(s) between humans, power structures and being effective (whatever that means in a given context) will in my opinion continue to be messy, fraught with uncertainty and full of opportunities for improvement. Hey, thanks for the incisive thinking and comment.

Pingback: What if everything ran like the internet? | BRYAN LENETT OFFICIAL WEBSITE - BryanLenett.com

very interesting indeed! however, as noted in posted comments, neither nature nor the internet are actually devoid of hierarchy –not to mention society and social institutions. It seems that the normative challenge for social and naturalist thinkers remains to be met at the democratic balance of equal liberty and acceptable differences, say, in reflective equilibrium, as wirearchy pushes for continual revision and recasting of given hierarchical strutctures in order to calibrate efficiency with sustainability (after all, the reasonable, fair terms of social cooperation must be sustainable)