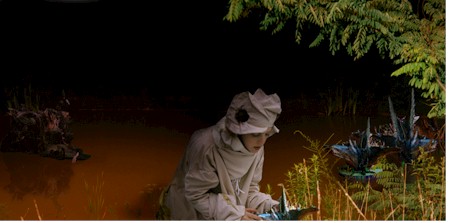

conception of post-civilization all-weather wear by mary mattingly

I‘ve added professor Clive Hamilton’s new book Requiem for a Species: Why We Resist the Truth About Climate Change to my “Save the World Reading List” (retroactively). It’s the natural next step after the 15 essential readings and really sums up where we (our species and our planet) are now.

Clive starts out by saying what climate scientists know but are afraid to say:

Over the last five years, almost every advance in climate science has painted a more disturbing picture of the future. The reluctant conclusion of the most eminent climate scientists is that the world is now on the path to a very unpleasant future and it is too late to stop it. Behind the facade of scientific detachment, the climate scientists themselves now evince a mood of barely suppressed panic. No one is willing to say publicly what the climate science is telling us: that we can no longer prevent global warming that will this century bring about a radically transformed world that is much more hostile to the survival and flourishing of life. This is no longer an expectation of what might happen if we do not act soon; this will happen, even if the most optimistic assessment of how the world might respond to the climate disruption is validated.

In the first four chapters, he reviews the science of climate change (including the methane release and other positive feedback loops that auto-accelerate greenhouse gases), explains why we have passed the tipping point, why we (and our politicians) want growth to continue forever, how our consumerist culture has evolved, why we’re prone to believe greenwashing, the psychology of denial, and the inevitability of the emergence of dangerous, corporatist-funded “junk science”.

Chapter 5 describes the civilized human’s disconnection from nature that has allowed all of this to happen. Clive explains the malleability of our mental constructs of reality, self, and belonging and how they (we) have changed our worldview. (The chapter includes a fascinating and succinct statement of the Gaia Hypothesis written by Plato in the 4th century BCE!)

In Chapter 6, he deconstructs the discredited ‘fixes’ to global warming: carbon capture, the switch to renewables, substituting nuclear energy, and the use of climate engineering (geoengineering). I think he underestimates the perils of nuclear energy (not only the massive cost of reactors and how they would bankrupt our already-overstretched economy, but the challenge to post-civilization societies of preventing, for the next million years, the last century’s human-made radioactive wastes from causing even greater devastation for millennia to come). But otherwise this examination of proposed fixes is a good update to George Monbiot’s Heat. Chapter 6 includes an interesting and terrifying review of the politics of geoengineering, focused on the deranged proposals of right-wing darlings Edward Teller and Lowell Wood, that leads to the horrific conclusion that, because it’s so inexpensive and tempting to desperate, arrogant people, unilateral geoengineering efforts are not only likely, but probably inevitable.

In Chapter 7, Clive explains what we can expect, based on the latest projections, when runaway climate change hits us full-bore over the next few decades:

- the uncontrollable burning of most of the world’s remaining tropical, subtropical and temperate forests due to latent heat

- the prevalence of desertification, disappearance of glacial melt, massive water shortages and endemic high rates of heat-related deaths in the world’s temperate zones (including the Western US and Canada; worst in Southern Europe, the Middle East, much Southeast Asia and most of Mexico and Central America)

- an ice-free world, with a commensurate rise, sooner or later, of 50-70m in sea levels

- unprecedented and chronic floods, storms and monsoons

- the death of almost all ocean life

- large-scale collapse of human infrastructure not designed for such extreme and frequent weather events

- massive numbers of climate change refugees, migrating (mostly north) thousands of miles in search of lands that are still habitable and arable

He dismisses human plans for resilience and adaptation in the face of such catastrophic (and specifically unpredictable) events, and says instead we must prepare for “a process of continuous transformation” of the way we live — societies and cultures in a constants state of rapid flux. He confesses:

It was only in September 2008, after reading a number of new books, reports and scientific papers, that I finally allowed myself to make the shift and admit that we simply are not going to act with anything like the urgency required… The climate crisis for the human species is now an existential one. On one level I felt relief: relief at finally admitting what my rational brain had been telling me; relief at no longer having to spend energy on false hopes; and relief at being able to let go of some anger at the politicians, business executives and climate sceptics who are largely responsible for delaying action against global warming until it became too late…

We [now] have no chance of preventing emissions rising well above a number of critical tipping points that will spark uncontrollable climate change. The Earth’s climate [will now] enter a chaotic era lasting thousands of years before natural processes eventually establish some sort of equilibrium. Whether human beings [will] still be a force on the planet, or even survive, is a moot point. One thing seems certain: there will be far fewer of us.

The final chapter on “what to do” focuses largely on learning to accept and deal with grief and loss. Clive explains:

For those who confront the facts and emotional meaning of climate change, the [death we mourn] is the loss of the future. [Our grief] is often marked by shock and disbelief, followed by… anger, anxiety, longing, depression, and emptiness [which we suppress through] numbness, pretence that the loss has not occurred, aggression directed at those seen as responsible, and self-blame… [Denial and avoidance are] defences against the feelings of despair that the climate science rationally entails…

Healthy grieving requires a gradual ‘withdrawal of emotional investment in the hopes, dreams and expectations of the future’ on which our life has been constructed. [But] after detaching from the old future [it is our nature to] construct and attach to a new future. Yet we cannot build a new conception of the future until we allow the old one to die, and Joanna Macy reminds us that we need to have the courage to allow ourselves to [first] descend into hopelessness.

conception of art after the collapse of civilization culture by afterculture

This is the reason, I think, why I am now driven to write upbeat imaginative stories set several millennia in the future, once the crisis has passed. It is easier and perhaps healthier to see the coming collapse not as the end of something, but as a period of disequilibrium, a challenge, that we must endure in order that our descendants can live in a much better society than the one we live in today. It’s an attitude of willingness for self-sacrifice that many of our ancestors shared.

Clive goes on to explain how the loss of our future brings about a loss of meaning, and so we have to create a new story about ourselves and our purpose.

He suggests that we will reach the point at which, as much as we respect the law, we will have a moral obligation to ignore it, to mitigate or at least briefly delay the onset of runaway climate change through illegal actions. As I have written lately, I think that is a matter both of personal conscience and personal worldview: I have come to appreciate, through my study of complex systems, that such actions, useful as they may be in achieving short-term benefits for those we care about, will ultimately have no long-term effect, and they entail considerable personal risk as our surveillance society anticipates and ramps up efforts to suppress such actions ruthlessly. But I also appreciate and admire those willing to fight the system despite those personal risks and its ultimate futility.

I come back to the four safer actions we can take now to prepare, I think, for the convulsive period ahead:

- Live an exemplary, joyful, present life: Be a model of living in the present, joyously, every day, living a life that’s aware, generous, responsible, sustainable and full of learning, wonder and love. Rather than dwell on the future or the past or what could have been done or is going to happen, focus on making the world better for yourself and those immediately around you now. Perform what Adam Gopnik calls “a thousand small sanities“. Seek to exemplify what Richard Holloway calls “an attitude of contemplative gratitude“.

- Re-learn essential skills and knowledge that will make you and your community more self-sufficient and resilient when centralized global systems — governments, big corporations, trade, industrial agriculture, energy etc. — fall apart. Learn to make clothes, or to grow your own food organically, or how to mentor a student to learn how to learn, or how to facilitate a group to work more effectively together. And learn more about yourself as well — how to make yourself well, what triggers you or frightens you (and why), what you do really well, and what you really care about.

- Discover your neighbours and connect with them, and learn how to build and live in community, where sharing is more important than owning. Learn how to care about, and even love, people you really don’t like very much. When hierarchies collapse, what we’ll be left with is community. Get to know yours.

- Work with others to help them, and you, to heal from the damage this culture has already done to us, physically and emotionally, and to cope with the fear, the guilt and the grief we all start to feel when we realize what we have done to this planet, with the best of intentions, and what we’re going to face as a consequence.

Thanks Dave!

What a useful overview of an important book

[[ I finally allowed myself to make the shift and admit that we simply are not going to act with anything like the urgency required… ]] … voila !! And why, yes, all that can be done is live joyfully and in an exemplary fashion, and write stories about what might be if the coming cataclysm helps the human species evolve in its understanding of consciousness, love and care.

It’s pretty obvious that there won’t be any future for humans. We will go extinct, rather soon now. We cannot survive the temperatures that are being projected, not much (if anything) will.

So what you do now with the time you have left is all that matters. If you want to write imaginative stories, then go ahead. If you want to survey the sunsets of the world, then go ahead. Make love, eat good food, enjoy life. It’s all that is left to the entire human species.

[[ We cannot survive the temperatures that are being projected, not much (if anything) will. ]] Might a (much much) smaller number of humans survive, maybe even for centuries, by adapting enough to begin, somehow, living underground ?

Great discussion of the book. Thanks

Pingback: Requiem for a Species « how to save the w...

Thank you for this excellent summary corroborating Dr. Guy McPherson’s reviews of the scientific data on climate change. As for actions in the present, your notion of writing “upbeat imaginative stories set several millennia in the future” is premised on the probability that some humans will survive the crises (as James Lovelock also suggests). I think we all need some form of carrot — optimism, hope, meaning — something to live for, a way to contribute, like your writing upbeat stories may provide for you (and us).

Increasingly I find myself wondering about what factors could help some people to live through the catastrophic changes. Educating and training younger people in practical and mental life skills, perhaps encouraging relocation, perhaps securing arable land, wilderness and urban survival skills, listening, observational skills…what would a university of life, or a training in resilience include?

Pingback: Requiem for a Species | Damn the Matrix

Thanks Janaia. I’m a big fan of Guy and hope to meet him some day. Interestingly, my premise for writing future stories is actually not that future generations will read them, but partly that current generations will read them and will find some comfort and perspective from them in facing the challenges ahead, and partly that, as a writer with the belief I have something important to say, I can’t NOT write such stories.

I think it’s important that young people learn the essential resilience skills but I’m not sure it’s our job to teach them (in fact it may be presumptuous of us to try to do so). I think our role is to listen to them and be prepared, if asked, to suggest courses of action open to them, and then to support them in whatever they personally and collectively decide to do.

“We [now] have no chance of preventing emissions rising well above a number of critical tipping points that will spark uncontrollable climate change. The Earth’s climate [will now] enter a chaotic era lasting thousands of years before natural processes eventually establish some sort of equilibrium. Whether human beings [will] still be a force on the planet, or even survive, is a moot point. One thing seems certain: there will be far fewer of us.”

~ Excerpt from Clive Hamilton’s book Requiem for a Species

More and more people are saying this. And it worries me, because while it may probabalistically predict the future based on the recent past, it also potentially sets up a self-fulfilling prophesy. “A self-fulfilling prophecy is a prediction that directly or indirectly causes itself to become true, by the very terms of the prophecy itself, due to positive feedback between belief and behavior.” (Wikipedia)

As more and more people conclude that nothing can be done about this mess we can be sure that THOSE people won’t be doing anything about it. And, often, these are just the sort of people we’d be needing to get stuff done about it, since they are better informed about the level of risk involved.

Pingback: Requiem for a Species | Collapsing Into Consciousness