dust storm, texas 1935; image from wikipedia

When co-founder of the Permaculture Movement David Holmgren recently suggested it might be better for the world if we were to try to precipitate global economic collapse in order to mitigate runaway climate change, he received a harsh response from Transition Movement founder Rob Hopkins, and somewhat more sympathetic responses from Dmitry Orlov and Nicole Foss. The second article (due out next month) in my series for Shift Magazine will talk more about this, but in the meantime I wanted to recommend to you Agency on Demand, a fascinating take on this debate, written by Eric Lindberg.

Eric’s point is that the markedly different positions staked out by well-meaning, informed people on this issue stem from their different worldviews — the way they see our human culture operating and functioning, how they perceive the world really works. What underlies those worldviews, he says, are our narratives, our stories of how we believe humans got here, and how humans think and act, individually and collectively, which is largely a conflation of our own personal stories and the stories of others we have chosen to read and integrate with our own.

A critical factor differentiating these diverse worldviews and narratives, Eric argues, is our perception of human agency — what humans are capable of doing, individually and collectively, when they share a worldview and when they do not. The more I study history, and the more I learn about complex systems and their intractability, the more I am coming to share Eric’s view that our agency is limited, and that our propensity for beating each other up for our different ideas and proposals for coping with emerging system crises and collapses, stems from an exaggerated sense of our own agency.

My friend Paul Heft wrote a good synopsis and reflection on what Eric has said, to some of his Transition colleagues, and he’s given me permission to publish it here.

Paul’s post:

Erik Lindberg’s essay on analyzing collapse narratives is insightful. Basically he’s questioning, do the assumptions behind our narratives still seem sensible, or are they merely comforting myths? Can people really make history the way we hope, especially given what we know now? Are we the conscious ones, or are we still deluded? Are we ready to give up our beliefs and move toward reality, or is that too uncomfortable?

I count myself as a radical, because for decades I have believed that the problems of the world are system problems–they’re not just isolated events, the consequence of particular circumstances or the decisions of particular people–and therefore the solutions require radical changes to the systems (economics, politics, etc.) by which we live. But radical changes to existing systems are difficult, they are constantly resisted by the existing institutions, by the powerful people that benefit most from the status quo, and by the masses of people who fear they will lose something if the systems in which they are embedded were to be altered. As Lindberg points out, the radical changes of the past, the political or economic “revolutions” or wars, have failed or have spawned terrible regimes or have had devastating unintended consequences.

Lindberg’s “Liberal” histories have a long tradition of rationalizing negative consequences, so that in hindsight we can claim to see continual progress with a few unfortunate episodes thrown in for color. It’s a very handy point of view for the ruling elites, but I don’t buy it. Lindberg rightly points out how many critics of the status quo, such as myself, are left feeling powerless to make the radical changes we feel are necessary, because we don’t see a path without the possibility of even greater harm; and I would add that we’re dispirited (for various reasons) by non-radical campaigns such as those the environmental movement and the Democrats conduct.

Lindberg states that the Transition Movement holds a kind of belief in the inevitability of radical change due to the inevitable decline of oil and other fossil fuels. The belief is that “people will find the joys of community and simple purposeful living far more compelling than the collapsing and increasingly alienating industrial structure of society,” so they will be eager to give up on the existing economic and political system.

Clearly [Lindberg] no longer has faith in “this sort of historical necessity” of a positive “revolution”. He sees the peak oil problem being too easily ignored; the energy descent it forces is too gradual, while the economy continues to support rather high prices for oil. My belief is that the rising cost of production of oil (and liquid fuels in general) definitely constrains the global economy, but not enough to force it to crash or to change its basic mechanisms. For decades there will be plenty of money to be made (by the wealthy) by keeping the economy running in its profit-generating mode, though we might be stuck in a perpetual depression. What Transition sees as opportunity “to build a better alternative,” most of the world will see as the opportunity for a higher standard of living slipping away. Lindberg doubts the chances “for a small and relatively obscure movement to gain widespread support and rework the wants, wishes, and expectations of the industrialized world, especially when the vested interests that control most media and spend trillions of dollars a year on advertisements will do everything in their power to stop it in its tracks.”

Lindberg sketches out how increasing numbers of people who are aware of the predicaments and injustices of the world feel themselves forced into a radical dilemma. They see the dangers threatened by climate change increasing in the direction of gross habitat destruction and even, possibly, the extinction of humanity (and perhaps most other species we are familiar with). They see that political leaders are unable to deal “rationally” with climate change and peak oil–all decisions are economic decisions and money is the only measure of value, preserving the economic system in its present form is the top priority, their charter to maintain the near term profits of the wealthy overshadows the “greatest good”–in every powerful nation, of every political stripe. They are beginning to see that the worldwide capitalist economic system is prepared to grind every bit of value out of the earth and our labors, regardless of the effects on habitats or on human welfare, for the sake of continuing to accumulate wealth and maintaining the powers that be. The great machine will grind on, more slowly or more quickly, and will brook no opposition. States are expanding their powers to control their populations, knowing that some resistance is inevitable. The quest for power, and the money to exercise that power, takes precedence over all other considerations. If revolution is needed, is that even possible?

At this point, many people in the Transition Movement might object that I ought to have a better attitude. In Lindberg’s terms, they argue that “a free and independent people must learn how to impose limits on their freedom and power” in a “possible triumph of free will”. We must choose to believe that people around the world can influence their leaders (cf. 350.org’s efforts) to lead us in sacrifices to halt climate change and deal with peak oil better–even though the politicians are paid by the wealthy to keep the economic engine grinding away. My own opinion is that this is a pipe dream, a delusion. A similar, common response is a call for faith, a belief in miracles (delivered by technology, or evolution, or movements, or whatever) as against cynicism: Yes, the situation looks grim, no solution is simple, maybe none is obvious, but if we give up then of course the results will be bad. This isn’t Lindberg’s attitude, and it’s not mine, I’m too much a believer in a “reality” that we need to discover by questioning, not just letting our desires lead us. But if you can develop this faith, this better attitude, you can continue campaigning, with hope, for many more years.

David Holmgren suggested a different way for us to radically influence the economic system: to bypass the leaders and the political process, and instead undermine the economy by stepping out of it. (Some localization efforts are a way to step out of the global economy, one consequence often being to reduce the contribution to its destructive activity.) He hopes that if enough of us around the world turn our backs on the global economy, it will crash (since it is presently built on a fragile foundation of enormous debt); the economic engine will grind to a halt and thus habitat destruction and greenhouse gas emissions will reduce tremendously.

Lindberg, despite his article’s title, doesn’t address this particular strategy much except as an example of the radical, morally ambiguous choices we are starting to feel forced to make. It’s unclear how practical Holmgren’s suggestion is. Would an economic crash really stop the global economic engine, or just interrupt it briefly? What would the state’s response be? Would Transition’s localization efforts be villified and even legally limited? How great would the suffering, and thus the backlash, be in the developed nations and the rest of the world? Might an economic crash–for any reason–usher in a fascistic political system and large scale war as it did in Europe during the Great Depression?

Lindberg warns that we “may have a series of unbearable decisions in the days and years ahead.” The collapse we foresee includes “predictable violence.” Our own planned actions will have results that are “neither controllable nor predictable.” Even nonradical actions, such as “just planting trees” or “building community”, are decisions not to engage in radical actions such as resistance to the system; such negative decisions will have unpredictable consequences too–Chris Hedges, for example, warns that impending fascism must be opposed. I don’t think Lindberg argues for no action, I think he is asking us to check reality and realize the dilemmas we face.

In the course of making such “unbearable decisions”, what delusions are we ready to give up?

- Do we need to believe that the economics of oil production will be the key driver in changing our economy and how we live?

- Do we need to believe that climate change can be stopped through political action?

- Do we need to believe in “the responsibilities of a citizen of a democratic society”?

- Do we need to believe that we can foresee the effects of our action or inaction, that we are confidently working for good and avoiding harm?

- Do we need to believe that the “bad guys” are the reason for the world not working as we desire?

- Do we need to believe that we are doing God’s work, or that humanity has a purpose as a species, or that Nature has a plan or key role for us?

- Do we need to believe that our activities now are building the better future we are desperately trying to imagine?

- Do we have faith in capitalism to “green itself” and make a better world, or do we demand that others have faith that undermining capitalism will make enough room for us to make a better world?

- Do we need to believe that consciousness is evolving so that there is a growing proportion of people who are as aware as we are?

- Do we need to believe that we understand people’s motivations?

- Do we need to believe in rational decision making?

- Do we need to believe that mass movements are necessary? that individual virtue is necessary? that our own contribution is important?

- Do we need to invent a new narrative that clarifies how we fit into the great sweep of history, that explains how we contribute to progress?

Questioning these things makes us anxious; we have grown up believing that we should be able to figure everything out, that there are right and wrong answers, that the world can be understood and explained (often according to rules and mechanisms), that reasonable people can come to agreement.

When Lindberg concludes that “Moral philosophy and deep spirituality may be our solace and salvation,” I think he is implying the need to step back and seek a larger perspective. Of course that just leads to more questions, but perhaps less anxiety, as we learn to take these things less personally: who are “we” that feel responsible for the world? Can the world get along without me? Who demands that my decisions be correct? Can I be open to others’ ideas, without judging them or myself as right or wrong? Do I need to feel in control of my future, or the world’s future?

Certainly I am anxious about the world and my role in it. Sometimes I’m sad or angry. Sometimes I’m depressed, feeling utterly small and powerless. Increasingly I’m able to accept the world, even though it will never fit with my ideals; it’s not an object made to my measure. Blaming myself or others doesn’t seem helpful. I practice meditation, hoping that I can avoid the domination of thought and learn to honor feeling, as a path to better knowing reality and realizing what actions to take.

. . . . .

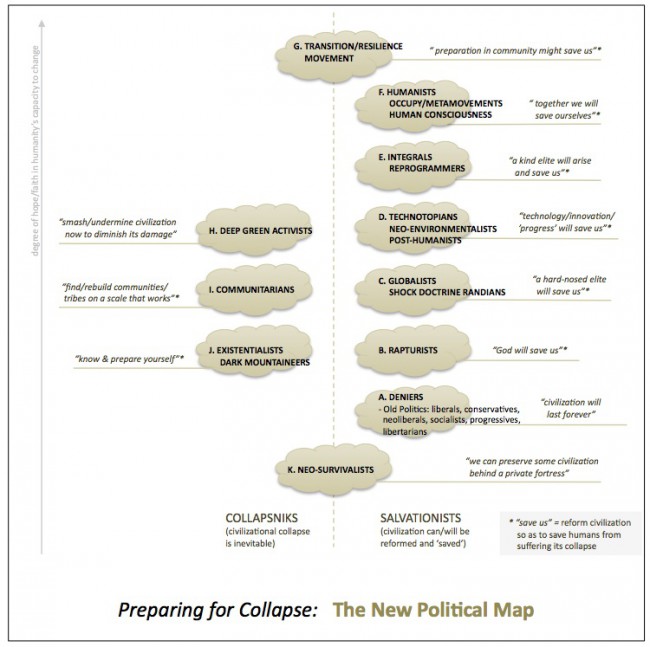

I don’t have a lot to add to what Paul has said, since his worldview and mine are pretty congruent. Eric urges in his conclusion “Let us be patient and tolerant with ourselves and each other.” That’s hard to do as we grow more and more alarmed about out future and our apparent inability not only to control it, but even to agree on what tactics and strategies are most appropriate to cope with what is coming. The Map above, from my post last spring, shows some of the worldviews of different groups in the 21st century, and what they each “need to believe”.

A number of my collapsnik friends believe that brutal fascism is inevitably what happens when those with wealth and power are threatened, as they certainly are by the global economic collapse we will surely face whether we try to precipitate it or not. So, they say, if some of us try to precipitate it sooner, we might end up being the scapegoats for its occurrence. Depending on your worldview, your narrative, and your sense of the potential for human agency, it may or may not be worth doing anyway.

My worldview, perhaps naively, is that economic collapse will sap the ability of the rich and powerful to bring to bear armies, militias, legal and media stormtroopers to try to hold off collapse or control the rest of the populace. And, also perhaps naively, I believe that in times of mutual struggle and despair most people can and do care about and look after each other, and that hence Mad Max collapse scenarios are highly unlikely. Perhaps that is just something I “need to believe”, and I am constantly re-examining it.

What is at the heart of many worldviews is a “need to believe” both in human agency, and in a better future. In the bullet points above, Paul might seem to be questioning this need to believe, but he’s actually saying, I think, that we would be well-advised to become aware of what is our own “need to believe”, and what is the “need to believe” of other informed and caring people, and how those different “needs” reflect different narratives of the human story (and of our own personal story), and different senses of human agency. And then to appreciate and respect those differences, rather than arguing about (or trying to change) them.

My worldview, narrative and sense of human agency have evolved greatly over the past decade, and continue to do so. But, as Beth Patterson pointed out in a comment on my last post, a shift from a salvationist to a collapsnik position may only be possible after a deep and painful process of dealing with the overwhelming grief that is often a prerequisite of such an acknowledgement of inevitable loss. We have to allow that process of our fellow caring, anxious human colleagues, and give them time until they are ready to ask themselves and listen to challenging truths, and until they have at least begun to process the commensurate grieving.

I believe that collapse (economic collapse, runaway climate change, and perhaps energy/resource exhaustion as well) is coming or cannot be averted, and that it will be unpleasant for most. But these days I am beginning to see collapse as a natural and inevitable process that will lead, in time, to a new equilibrium of life-on-Earth, with the much-smaller human population becoming, as it was for its first million years on the planet, a small and incidental player in the panorama of life on Earth, living joyfully in places we are naturally adapted to live.

For now, at least, that’s what I need to believe.

If Ur anxious about the future then Ur not philosophical enough !

Change is the one constant of the universe and since the earth won’t last forever then carbon based life won’t last forever either.

The process of evolution first got biodiversity in the water then biodiversity on the land.

The solar system is now barren, in the future the solar system will be full of biodiversity but to get there will require creative destruction on a earth planetary scale.*

So humans can be considered to be as Douglas Adams wrote, “mostly harmless”. Merely a force of creative destruction somewhat more powerful than blue-green algae.

How joyful is that !

* the next age will be the genetic age which comes before the ?silicon? age

Very though-provoking. Thank you Dave.

First, I feel guilty, or perhaps odd, that I don’t spend a lot of time on grief for the disappearing abundance that was.

For me personally, life has seldom been better. I’m not talking about money. I’m more or less as poor as ever, and by choice outside the consumer system. It’s getting better for community, for my opportunities to grow – partly due to my role as an alternative radio producer, but also by discussions like this one.

That said, I need to believe the world of my grandson will not be so cruel as to wipe him out, or make him suffer greatly. If there is some small thing I can do to help that better outcome, I am obliged to do it.

Human agency is much smaller than we think. After reading a lot of history, I subscribe to the school that finds wide-spread human movements are ready, and then sparked, by some now legendary individual to whom we ascribe that change. Neither Napoleon, Ghandi, nor Hitler were really the cause of what is ascribed to them by history.

Humanoid footprints at least 800,000 years old were found on a beach in Britain last year. Those are the tracks of an odd mammal living at very small scale in tune with nature. During the next 100,000 years of human habitation there, the climate changed from very cold to being a Mediterranean hot zone. We presume humans kept living through that change. We also presume the change was more gradual than we are about to experience, although we are not sure of that.

The point is, for those who think humans will go extinct, I say mass humans will go extinct, but small-scale human groups will continue on through pretty well anything. So let’s stop clubbing people over the head about human extinction, and making ourselves sick with worry about it, and stick with the very serious issues at hand.

I don’t see a solution either. Humans have a long history of dropping out of insoluble systems. The Christian Church was in part built by those moving away from the corrupt and then collapsing Roman empire. They insisted on the need to support all in the community, even the weak and old, by pooling resources. Their mind-set was that even torture or death merely reinforced their belief.

All through the late Middle Ages, when life again became bleak by the Plague, hopeless social domination and other forces, groups of humans “dropped out” to build Monasteries which grew their own food, made their own clothes and so on. These ideas are not new.

Many historians believe the modern economy, including the idea of work organized according to a clock, emerged out of those Monasteries. It took a few centuries.

Likewise, we do not know what will come of currently small efforts to create local food, currency, community and so on. These may be seeds of the next wave of social life. The whole spy network, fascism, and so on, may develop for a hundred years or less, but it will fall down. Then we’ll really see what is next – or at least our descendants will.

All I can offer is this: follow what your heart says to do. Don’t settle for a half-life you really hate. small change is better than no change. Don’t hate others for their position in the matrix. Never be so sure of your own “truth” that you can’t tolerate others.

That doesn’t seem like much.

Alex

Radio Ecoshock

Damn, this ain’t Facebook and there’s no ‘like’ button! (I don’t really think that. I hate Facebook.) Alex’s comment above resonates with me as much as this article. How awesome to be among kin :-)

I really appreciate the questioning approach. If there’s one thing I learned from a decade of teaching (in the mainstream education system) it’s that asking questions is a far more effective pathway to learning than telling anyone anything. I don’t teach anymore, but I do carry with me what I learned during the lovely decade I spent in the classroom.

But, as always, I differ in some respects (is that part and parcel of our march toward ever-increasing complexity that causes us to accelerate our burning up of entropy to the point of collapse?)….

My thinking is that we are doomed to collapse, yes. And the outcomes re: human survival (or any other species, for that matter) are unpredictable. Does this mean I become a nihilist and just wait it out? How depressing. I’m depressed enough as it is, and increasingly concerned for my family in the UK, where food security is already a thing of the past and most people still don’t know that. I have accepted that collapse is coming, but I don’t accept what will happen as though it’s ok. I think those are two different forms of acceptance, and I cannot numb myself to feeling no matter how much I understand and accept the inevitable. I’m not ok with the suffering that is coming, and already all around us in so many places.

Therefore I can’t help but live with purpose – I dunno, maybe it’s just my default. If I see pain and suffering I do what I can to ease it. (Do I have an inflated sense of my own agency? Maybe. Maybe that’s just part and parcel of growing up with a disabled sibling and noting the contrast.) It makes sense to me that even if I can only ease that suffering for a short while it’s still worth it. So I don’t subscribe to this big-picture-only version of the collapse narrative (although I am a big-picture perceiver as opposed to a detail freak). I think the little things really matter – as the individual’s experience is their only reality.

I think it’s still worth feeding the hungry today, even if they will die tomorrow anyway. I think it’s still worth picking up litter so that animals don’t choke on it or get injured by it, even if it’ll just happen tomorrow anyway. I think it’s still worth pulling shark-bait off hooks so marine life can swim on and not die a painful death today. I think it’s still worth planting trees so that an ecosystem can flourish for another day or so. I don’t see this as futile because I am not only thinking of the long-term and collective whole. I am perhaps projecting somewhat, but I would like my unique and individual (yet connected) life to be nice for as long as it continues, regardless how it ends, and I sense that others feel the same.

So, taking all of the above, and acting with purpose, my work is to do what I can to remove artificial barriers to survival so that we may all have a chance to live another day. I’m not fucking with Mother Nature – she don’t negotiate. But I am down for removing shark bait from hooks – so that that artificial barrier to survival is removed. I’m down for crashing the financial operating system, so that that artificial barrier to survival is removed (think of the world’s poor who don’t have enough to eat – simply because of the price barrier, not as a result of climatic conditions, which will, of course, worsen for everyone). I’m also down for helping people to powerdown, as that will give them a chance to survive in a post-peak future, however slim, by assisting preparation and removing barriers (mainly cognitive and emotional, rather than practical, in many cases).

I don’t need to meditate to feel – I am an empathizer by default, and I spent half of yesterday crying for Marius the giraffe (I couldn’t help it) and the sharks (and other marine life the media ain’t mentioning) that ‘we’ are baiting and murdering in WA. What’s wrong/right with me? I sense that if everyone were to feel enough to cry at such things we wouldn’t be allowing them to happen.

Thanks Kari. Appreciate your clarifying the distinction between accepting the inevitability of collapse and ‘accepting’ the suffering that it will bring. Suffering is always unacceptable. It’s human nature (thankfully I think) to do what we can in the short term, even if in the long term it may not make a difference.

And also the fact that we lack global agency — we’re unable to turn around the Titanic of our civilization — doesn’t mean we don’t have powerful agency in our own communities. That’s why an increasing number of us, I think, are focusing our preparations on community-building, and on understanding how/why we’ve lost our sense of community, and what might be done to recreate it. I am ‘hosting’ a forming intentional community here on Bowen Island, and am fascinated to observe how they are self-organizing, self-selecting, and developing deep community-building skills, showing what is possible.

Your final sentence “I sense that if everyone were to feel enough to cry at such things we wouldn’t be allowing them to happen.” is a very profound and provocative statement. I’m not sure I agree with it, and that is very troubling. What does it mean if/that we allow them to happen anyway?

Reposting my e-mail reply to Alex:

Thanks Alex. Sounds as if we share a narrative. And your advice seems wise.

I agree with you that talk of human “extinction” seems hyperbolic, and kind of beside the point if we’re going to have reduce our numbers by 90% or more to be able to live in a post-industrial world.

My self-determined role for now, once I’ve finished the series on complexity for the new Shift Magazine, is to learn to craft stories about what life might be like a few millennia from now. I’m pretty good at imagining possibilities, and my sense is that human societies of the post-collapse future are likely to be astonishingly diverse. It will be a good time to be alive. As it is now, for the time being.

Thanks for all you do — much appreciate your radio program and the perspectives it offers.

Is there anybody ready to accept the end of the world? I do not mean the reality, but the world we see and have been seeing, narrating and accumulating narrations for 100k years.

“I see the world” is the fundamental, pre-conscious and inevitable assumption on which our cognition and all the worldviews are and have been built. The implication is a static nature of the normalized worldview. At least ”I” (as living system), “the known world” (perceived and explored), and the unknown (rest of the whole) must be static.

In reality the world is not. It is becoming and includes us, our minds and our culture (totality of “worldviews”).

My initial question is well grounded in my experience on social fora – dynamics can be applied to our development exclusively, otherwise it is a taboo. Breaking the taboo is really the challenge, but on the other hand understanding the process we are instead of the world we have been given we could replace irrational behaviors and collective impotence by rational common decisions. From my side I am open to argue the thesis.

Dear Dave

As always, your observations are thought provoking. One of the things that strikes me about the reactions that David Holmgren’s article has elicited is that David invented something wonderful, yet feels that he has had little impact on how humanity is by and large going about its self-destruction with iron determination. He feels he has little agency. If David hasn’t made much difference, what chance do I have? I had three children, and they all turned out to be very different people. That was my first clue that maybe I didn’t have much influence on how those little seeds grew. Now I have two grandchildren, and I think my influence is even more remote. So…am I supposed to think that I have the ability to influence a politician?

In the US, and perhaps in Canada, stories come to neat conclusions. By and large, most of us have felt that we were in control of our own stories. We may now be entering a period of time when we will not be in control of our stories. There was a time in Europe after WWII when there was a lot of experimentation with stories where random things happened. An example of that kind of story might be Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion or Claude Lelouch’s Les Miserables.

There was also a certain tradition of beauty embedded in a random world. The dance with Anna Karina and two small time criminals in Band a Parte. Arletty in Children of Paradise. A current example is the Italian film A Great Beauty…the world may be populated with fools and charlatans, but once in a while one can experience great beauty.

It seems to me that some of us may need to rebalance between trying to save other people (and perhaps ourselves?) and simply enjoying the beauty that still exists. It has become evident that humans have a limited amount of concentration to spend. Less concentration on saving the world leaves more concentration for enjoying great beauty.

Don Stewart

Pingback: There is No Alternative (Paul Shepard for the Twenty-First Century) « Robin Hill Gardens

Pingback: There is No Alternative, or Paul Shepard for the Twenty-First Century « Robin Hill Gardens

Dave, thanks for addressing my reflections in the post, I’m honored. I suppose the main point I was aiming toward at the end of the piece is that we must examine our own beliefs critically—probably some of them are delusional—so that we might get closer to the truth. That examination can be scary; on the other hand, some of our anxiety results from hanging onto beliefs (which often means building our identity around them). If we can recognize the delusions—especially the ones about our agency and our personal role—and let them go, I suspect that we will feel more free (even if we cannot control life).

I agree that we need to respect different worldviews, and appreciate them to the extent that we can. (I don’t know how much we can influence the views of others.) Holding our own views lightly doesn’t mean that everyone else’s views are equally valid; some judgment is still called for. I recommend that we listen to others, and consider that their different views might be at least partially true and might be motivated by some values that we hold in common. Our beliefs will probably change (if we keep ourselves open), so we should take it easy on ourselves and avoid anxiously holding ourselves to standards based on believing that we are the change agents that the world has been waiting for, that humanity/life depends on.

In looking at the comments on this post, both here and at resilience.org (http://www.resilience.org/stories/2014-02-10/how-our-narratives-inform-our-hopes-for-change), I tried to fit them into your “New Political Map”. Some of the attitudes expressed fit fairly nicely:

F. Humanists, Occupy/Metamovements, Human consciousness

–It’s hard to accept forthcoming suffering.

–Don’t give up on the possibility of collective, rational decision making.

–Reform the system to make it sustainable.

–Act now so that we can believe in a good future for our descendants.

J. Existentialists, Dark Mountaineers

–There’s no need for anxiety, our history/future isn’t important in the grand scheme of things.

–We are undergoing a needed, if painful, correction in the way humans live among others on Earth.

K. Neo-Survivalists

–Learn skills, be adaptable, increase your chances of survival.

I have trouble fitting some other attitudes into your schema (nor do I easily see how to fit them along Albert Bates’ Transformation/Resistance axis at http://peaksurfer.blogspot.com/2014/01/recharting-collapseniks.html):

Yes, civilization will likely collapse, our agency is limited, but:

–We can claim agency on smaller scales, even if not on a global scale. (This sort of fits under “G. Transition/Resilience movement”.)

–Small acts are fine. Ease suffering, increase chances for survival, be artful.

Also: Though not in control, we can enjoy beauty.

Any thoughts on this?

Speaking of narrative, here’s a reminder of something I’ve never seen mentioned in my reading on collapse:

Collapse is a metaphor.

Close your eyes and imagine something collapsing. Describe what you see. Now you have a great a description of what won’t happen.

Collapse is poetry gone stale. Stephen Harrod Buhner writing on Poesis is no doubt relevant here. (his new book is due out next month, I think)

I remember Dave Holmgren mentioning in his Principles and Pathways book, a gap between scientific and spiritual approaches, an integration/synthesis which permaculture doesn’t quite achieve. The presence of that gap/existential void is what we’re feeling now.

That’s all.

The empire has always been going to end. The human species has always been going to overshoot. Rather a lot of people live in warzones, and many have come to a sticky end in the past century.

I’m reminded of Bono’s harrowing line in ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’.

“Tonight thank God it’s them instead of you”.

Thing is, now we’re starting to doubt that God will keep us safe.

A hundred years since 1914, and the knothole Beth referred to last post, is still where it was when the existentialists were grappling with it.

I think we’ll grieve our stories one little fantasy at a time. I’m in the throes of grieving a relationship that was mostly fantasy. In your last post you were someway through grieving your own personal fantasy.

Keep going!

Disillusionment hurts like hell.

That’s all.

By the way, to be clear, from memory, it was Holmgren himself who wrote that permaculture doesn’t bridge this gap. He mentioned Steiner’s ‘spiritual science’ as a good attempt. I’m more drawn these days to other approaches that don’t have the baggage that can come with Steiner – such as Henri Bortoft’s “Taking Appearance Seriously”.

Currently reading Garry Richardson’s “Philosophy of Conscious Action”(1987), which seems very promising as a second approach to the summits Steiner climbed, without the baggage.

Paul, I think my chart probably needs updating to reflect some of the nuances that have emerged in the last year, especially around the “existentialist” worldview. I’m at a conference today featuring Tim DeChristopher, Ursula LeGuin, Joanna Macy and Kim Stanley Robinson. So far it’s been a Humanist Revival meeting, with “amens” (the humanist variety: ovations) for every “all we really need to do is…” and “we really need to do… now” (count: 37 such statements in the first 3 speeches).

John: I think collapse is an unfortunate term, since it brings up in most people’s minds a drastic, sudden change. The end of our civilization will come about over decades, with some sudden events but a lot more incremental ones. Someone once said that humans tend to overestimate how much things will change in the short run, and underestimate how much they will change in the longer run. A few decades is plenty fast enough for me, but far too slow to capture the attention of the majority of distracted people. Not that it will make a difference, in the longer run.

Great post, and great comments – much appreciated, this gives me a lot of food for thought!

Reply to John Graham: On the gap between scientific and spiritual approaches, I like Ken Wilber’s “The Marriage of Sense and Soul.” But to balance Wilber’s version of “Integral theory,” I highly recommend Edgar Morin’s “Homeland Earth.” Morin’s “Complex Thought” also dovetails very nicely with the themes of the above post (and might inform Dave’s series of articles on Complexity).

And thanks for the reminder to keep an eye out for Stephen Harrod Buhner’s next book.

“The adventure remains unknown. The Planetary Era may possibly come to naught before it has even begun to bloom. Perhaps humankind’s struggles may lead only to death and ruin. However, the worst is not yet certain, and the game is not yet over. In the absence of any certainty or even probability, there is the possibility of a better world.

The task is huge and unassured. We cannot eschew either hope or despair. Both holding of and resignation from office seem equally impossible. We must have a ‘passionate patience.’ We stand on the threshold, not of the last, but of the early stages of the battle.”

– Edgar Morin, Homeland Earth

Glad to have found your site and look forward to sharing in your grapplings further.

I like reading widely and in different fields others’ worldviews because I

find that everyone’s vantage point affords them creative windows that others may fail to see. So even if I find them exorbitantly New Age or excessively and rigidly rationalist, all have something to add. You don’t need to subscribe to someone’s worldview to drink their wisdom.

I think this is why the divide and conquer tactics so rife in our society are doubly destructive – they relentlessly pit us against the possible wisdom of another while fuelling our over-excessive belief in out own agency along with our hatred of The Other. So you have the bizarre scenario of millions of people bemoaning what’s going on and refusing to do the very thing that may possibly be giving the greatest fuel to the status quo – refusing to own our own shit. If we need to be a stronger collective in order to stop what needs stopping, we need to start owning our own shit on an individual basis so that we become safer to be around. Jung summed it up when he said if something is not made conscious it appears outside as fate.

Some very insightful stuff. Most of those are the types of questions that need to be asked. They are the types of questions that take the emotion out of ideas. And this is quite necessary I think at the moment.

But maybe you should be careful to ask such base questions such as “Do we need to believe that our own contribution is important?”

In a hypothetical egalitarian world of complete consensuality and equality of personal responsibility this might not be such an important thing to believe. But in our compartmentalised, measured, quantified society as it is, I think we certainly do. To not do so quickly reveals oneself as a meaningless piece of space flotsam, eating, fighting and fucking because it feels good.

I’m also failing to see the point of you asking this type of question: is it nihilism that drives you to do so? A new atheism? Abandonment of love?

Tristan, I think I understand your concern regarding the question, “Do we need to believe that our own contribution is important?” Here’s what I was trying to get at.

Whether my life seems meaningful is really not the issue–I might find meaning in several different ways, perhaps in different areas of life. But I want to face Eric Lindberg’s question of whether I have agency on the world stage, are my colleagues and I intentionally making history?

If I need to believe that my own contribution is important, then it will be impossible to even consider that perhaps I cannot effectively act as an agent of history–so I will delude myself regarding my role in the world, and feel terribly frustrated whenever I feel ineffective. Instead, I think that I can reduce anxiety by facing reality without assumptions, taking reality as it is, even if I tentatively conclude that I’m not able to transform the world in the direction of my ideals.

Others (perhaps you?) reject this approach, preferring to have faith in their visions of transforming the world, pressing forward to make the desired changes. I certainly don’t want to tell you to give up.

Pingback: Linkliste “Kollaps” | substruktion