This is a fictional excerpt from the diary of my great great grandfather Theo Pollard, “written” in 1899. I’ve actually read his 1899 diary, but it contains little but reports from the newspaper and information about family visits and his tailoring clients. But if he were to write a history of his family and neighbours, I’d like to believe this is what he’d write. The facts cited in this story are accurate; the opinions are merely my speculation.

_______________________________

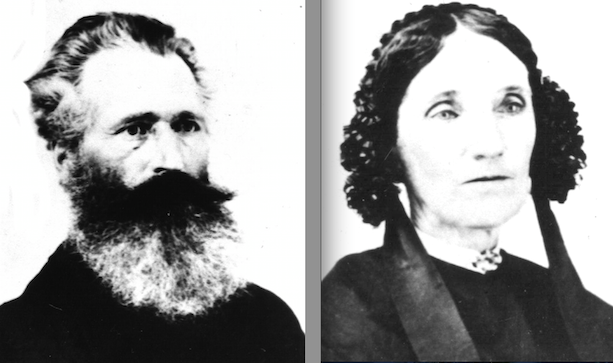

Theo and Hannah Pollard, 1896 (photo thanks to mazzey, who’s related to Theo’s son-in-law)

I’m Adolphus Theodore Pollard, a tailor in the city of Toronto. Everyone calls me Theo. It’s 1899, the close of the 19th century, and I’m 64. This is a brief history of my family and my people, the brave settlers — First Nations and European — who came to Toronto Township as farmers, fishers and hunter-gatherers, looking to carve a life together out of the wilderness in this new frontier. While this history focuses on my family members, it is, I think, pretty typical of the families of our time.

My grandfather was Joshua Pollard Sr, who in 1792, at the age of 20, migrated to the newly formed Province of Upper Canada from Billerica, Massachusetts, and then, in 1807, at the age of 35, took his 26-year-old wife Mary Ann Weitzel and his two young children John (age 6) and Betsy (age 2) from Saltfleet on the West of Lake Ontario to Toronto Township, Peel County (not to be confused with the City of Toronto, which was then called York, which is further east).

1. “Proving Up” and Starting a Family

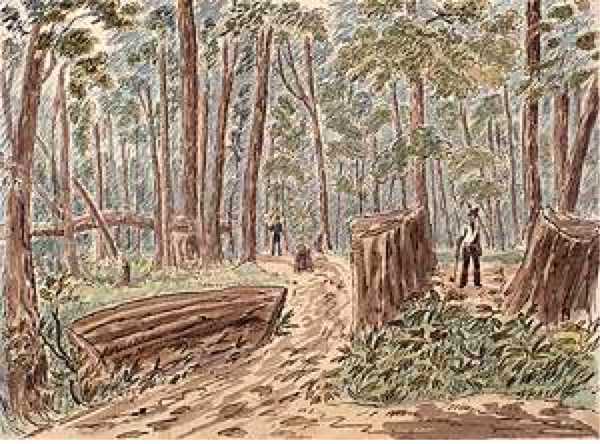

(image: depiction of the clearing of Dundas Street, Toronto Township, to open the way for settlers, 1796)

(image: depiction of the clearing of Dundas Street, Toronto Township, to open the way for settlers, 1796)

Earlier in 1807 Joshua Sr had applied for a grant under a new provision made principally for United Empire Loyalists which allotted 200 acres of property (mostly in areas yet to be surveyed) to disgruntled Americans willing to turn their backs on the newly independent United States and pledge an oath to the British Empire and its then-monarch the mad King George III. My grandparents then spent a year or so squatting with other immigrants awaiting survey completion at the foot of Bay St in the village of York with their two children. Their third child, James, born that year, died before his 1st birthday.

Between 1807 and 1812 about fifty families were granted 200-acre plots of land in the Township, recently purchased from the Mississauga First Nation. The grants were made on condition they were “proved up” within two years of the date of the grant. “Proving up” entailed meeting minimum requirements to prove intent to live there: building a home (my grandfather’s wood frame and log house was 38’ x 26’, twice the minimum required size), fencing and clearing more than five acres of the heavily-forested property (with densely-packed trees often over 150’ high), digging a well, and clearing the road in front of the property sufficient for safe passage by horse-drawn carriages. With the reciprocal help of several of his new neighbours, including my wife’s grandfather, Henry Shook, my grandfather received his certificate in 1810. “Proving up” was all done without artificial light, motorized tools or electricity, and wood was the only source of heat. That’s still largely the case on the farms, though here in Toronto we now have the new electric lights and a coal gas boiler that provides heat for our radiators and hot water to our bathroom and kitchen.

In 1808, Joshua Sr had applied for and received a licence for an “inn and ale-house” on his property (the first between York – now Toronto, and Wentworth – now Hamilton), which is why he had built such a large home. Their 988 sf home would soon house a dozen family members (a normal size family for that time and place), visiting preachers, travelers and mail deliverymen, and a bar.

Six of the ten children born to my grandparents once they’d settled in Toronto Township, between 1808 and 1822, would live into old age, as would Joshua Sr himself (at age 77). My grandmother would not be so fortunate – she died in 1823, at age 42, leaving her husband to look after their ten remaining children ranging in age from 10 months to 22 years. John, the eldest and the only child over 18, died just three weeks later. There was an epidemic of yellow fever across North America at that time and I’m told that was their cause of death. There was also a one in eight chance that a woman in those times of very large families would die from complications of pregnancy or childbirth. My grandfather promptly re-married, but had no children with his second (or third) wife.

While historians tend to focus on the “loyalists” who objected to war with Britain in 1776, most of the first American settlers in Upper Canada who arrived, later, in the 1790s, were, my father told me, not particularly pro-British. At the time, the economy of the Northern American States was chronically struggling. Large family sizes made it increasingly difficult for the new mostly-farmer American nation to continue to offer sufficient land to its young men for the prevailing subsistence agriculture. The cities, teeming with desperate, unemployed immigrants, were violent, exploitative, unpleasant places to live. In 1792 the Northern American States were in the grip of an economic recession brought about by counterfeiting, and the resultant distrust of currency seized up commerce and trade. It would soon be followed by the panic of 1797, caused by the insolvency of the Bank of England, which collapsed land prices and led to many bankruptcies and foreclosures.

And, while most of those from Massachusetts had recently fought fiercely for independence from Britain, by the 1790s they were free-traders, seeking peaceful relations with Britain so that their manufactured goods and resources could be shipped to new markets. In 1807 the Americans introduced an embargo prohibiting ships from its ports from entering foreign ports. Jefferson’s Embargo Act was intended to force the warring British and French to stop interfering with American shipping by cutting off supplies to both sides, but its main effects it seems were to bring about the Depression of 1807, and to help fan the animosity that led to the War of 1812.

So it is likely that immigrants like my grandparents were economic opportunists more than ideological British Empire patriots. The offer of so much free or nearly-free land, far from the desperation of New England’s struggling farms and cities and political turmoil, would have been hard to resist.

They were enabled as well by the frenzy of private turnpike (toll road) building that began in America in 1790 and lasted until the onset of war in 1812. It would not have been that hard to travel by horse-drawn wagon or coach from Boston to Albany and then to Niagara (then the site of government of Upper Canada), and thence petition for land deeper in the new territories.

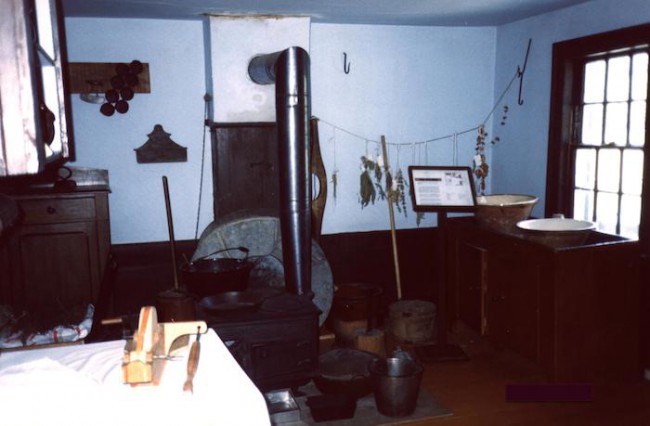

The Bradleys’ house, as it looked in the 1830s

In the early 19th century farms were subsistence – little trade was done with other regions or even neighbours, other than in the sawmills, grist mills and blacksmiths’. Wheat, barley, oats, peas, corn, potatoes, carrots, beans, squash, pumpkins and hay were the main crops, though fruits, nuts and berries were also grown. Chickens, sheep, cows, pigs and goats were raised for food, and horses and oxen for labour. Fishing in the river was prohibited by the terms of First Nation treaties, which preserved for them the areas on either side of major rivers, though these laws were seemingly breached, and trade with the First Nations (in this area, the Mississauga tribe) was common. And of course, alcohol was a major beverage and escape of the times, though coffee, tea and chocolate were surprisingly available even then to most. Settlers brought their own seeds, and acquired farm animals, tools and fabric in the port at York (some tools were even provided free by the government to new settlers). Everything else was made or grown locally.

From my father’s stories, I’d guess that life in those times was as hard, violent, and repressed as it is today in these dark days at century’s close. Short growing seasons, long, cold winters, relatively poor soils, endemic alcoholism, political instability, a lack of education, and combination of political and religious patriarchy most likely meant that much of each day was spent at work, at school or home-schooling (elementary grades only), and in prayer. It is probable that, as with some like the Amish even now, children in those times were routinely beaten and otherwise cowed, sexual abuse of women and children was tolerated and not spoken about, and abuse of animals was common.

Things for the powerless haven’t improved much nearly a century later: the occupation of adult young men and women living at home in rural areas is still listed as “farmer’s son” and “none” respectively in the census, reflecting the perennially low status of unmarried women. Young women in those days were married off quickly – usually between age 18 and 23 – and immediately began having families of 6-17 children (my own family of seven children is considered, these days, rather large). Divorce was of course not available to either gender.

Early marriage and large families were to some extent a necessity of pioneer life. Children were needed to help work the farm and do the considerable work in the house – food preparation from scratch, gardening, tending the animals, making soap and candles, making and mending clothes, teaching younger family members, looking after the sick, the very young, and the very old. And they were needed to support parents in their old age. There was an enormous amount of work to do, far more than any single person of either gender could manage, or any couple with a small family.

Failing to find a spouse when you were young, then, meant you became a burden on your parents or siblings, since you had to live with them and, if they died, probably find somewhere else to live. Although some marriages were arranged, in accordance with the culture of the parents’ families, there was considerable urgency to make it happen for both genders of young adults, even without parental pressure. And there is evidence that both young men and young women were looking for partners of character (hard-working, competent, healthy, perseverant, kind, not prone to alcohol addicition), for the long, hard life together ahead, so that physical appearance seems genuinely not to have been a factor in partner choice at all, for either gender.

That had not really changed by the time I married Hannah in 1863 (she married me, a homely and scrawny tailor, after all). My four eldest children all lived and married during the years of the two-decade Long Depression we’ve just seen the end of, so their pressure to marry has been dictated to some extent by “two can live as cheaply as one”, and their families thus far have been half the size of mine, and they seem content with, or resigned to, the city life they’ve all chosen.

2. First Nations Neighbours

The Mississauga First Nation ceded parts of what became known as Toronto Township to the British for loyalist settlement purposes, in exchange for cash, at the turn of the 19th century (1805), and at that time they retained exclusive hunting and fishing rights along the area’s rivers. An additional purchase by the British in 1818 added more settlements in the north part of the Township, and soon after that the Mississaugas sold off their remaining lands (for a pittance: I hope that one day they will receive a settlement to address the inadequacy of what they received then) and in 1847 they moved west to a part of the Six Nations reserve, where their descendants remain today.

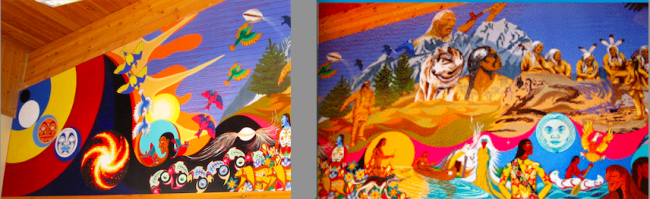

Parts of the Anishinabe story mural telling the story of the Anishinabe Nation, the migration of the Mississaugas to the Credit River, and the prophecies for the future, at an elementary school in Hagersville, Ontario

The Mississaugas are part of the Anishinabe Nation, and they migrated south in the 17th century from the north shore of Lake Huron to the Golden Horseshoe area. Their traditional way of life was to hunt and fish and grow fruits and vegetable crops in the summer, and then move inland in the winter, living mainly off what was preserved of their summer harvest. They traded with the French fur traders (the Credit River in the area is named for the credit the fur traders gave them).

During the War of 1812 the Mississaugas fought bravely alongside the new settlers for the British against the Americans, whose policy of systematic genocide would soon produce the Removal of Indians Act, calling for the total expulsion of all First Nations people in America to areas west of the Mississippi River.

Evidence is that relations between the Mississaugas and new settlers in Toronto Township were relatively good during the early part of the century. It appears the Mississaugas taught the European and American newcomers crop rotation, corn/squash/beans (“three sisters”) polyculture, indigenous medicine using local plants and herbs, tapping maple trees, hunting and foraging native edibles, snowshoe and canoe-making. It’s not clear the Mississaugas got much if anything in return. An early historian says my grandfather, whose land directly abutted the Credit River fishing and hunting grounds of the Mississaugas, died “beloved of the Red Man”. The new settlers certainly were indebted to them, though there is no official record of significant interaction with them.

In the latter part of this, the 19th century, a huge European influx of refugees fleeing from political oppression and famine, deforesting most of the area, and the proliferation of mills along the rivers, damaging fish stocks, essentially drove the Mississaugas out of the region entirely. In the process, their numbers were ravaged by diseases contracted from the newcomers, possibly reducing their total population by 90% or more. Like many First Nations peoples, they now live in small, impoverished areas totally inadequate to the pursuit of their traditional way of life.

3. War and Politics

The War of 1812, a spillover of the long ongoing war between Britain and France, brought the first wave of immigration to Upper Canada to a halt.

There were four causes of the war:

- a series of trade restrictions introduced by Britain to impede American trade with France, a country with which Britain was at war (the Americans contested these restrictions as illegal under international law);

- the impressment and forced recruitment of American seamen into the Royal Navy (since there were no formal American citizenship papers in those days, the British deemed anyone born in Britain to be subject to British military draft);

- the British military support for American First Nations peoples who were offering armed resistance to the expansion of the American frontier to the Northwest; and

- a desire on the part of some in the United States to annex Canada.

Upper Canada was somewhat removed from the key actions in these disputes, but the war threatened the sovereignty and security of Upper Canada, and access to needed goods from Britain and other colonies, so it is not surprising that many of Toronto Township’s newest settlers were prepared to fight for the British. Nor is it surprising that the Mississauga First Nations joined them.

In 1812 there were only about 400 settlers in all of Toronto Township; almost all of the approximately 100 able-bodied (i.e. aged from about 17-55) men from the Township served in the war, mostly as unpaid Privates with the all-volunteer Flank Companies, and with little or no training. My grandfather, then 40 years of age, enlisted early and fought for the duration of the war, notably at the battle of Queenston Heights, alongside many of his neighbours.

The war was all-consuming, essentially bringing economic activity in the area to a halt. From the lakefront at Lake Ontario, the families that were left behind could witness the fires of the 1813 fall of York to the American invaders. The Americans looted and set most public buildings ablaze. Most spectacularly, settlers for miles around could witness the burning of ships under construction by the retreating Upper Canada forces and the blowing up of their sizeable weapons and ammunition magazine, to prevent them falling into American hands. The magazine explosion was so violent it purportedly killed 1/6 of the invading American forces. The fall of York was followed soon after by the fall of Niagara.

After that, however, it became a war of attrition, with neither side winning battles consistently, and troops on both sides withdrawing, exhausted, to preserve numbers for whatever battle came next. Americans in the New England states, furthermore, had no interest in this war, which disrupted their vital port trade; there was even a move by New England states to secede from the new American nation in protest over this needless war. As for the British and French, they did not consider the North American arena to be essential to their European (Napoleonic) wars, and while the British did burn the American White House and Capitol in Washington in 1814, along with many public buildings, it did not stay to occupy it, not considering it a strategic asset. By then popular support for “Madison’s War” had vanished, and both sides quickly agreed to an armistice in 1814, the Treaty of Ghent, with all pre-war borders and agreements restored. Britain was flush from its victory over Napoleon at the time, and war-weary, especially after its debacle at the Battle of New Orleans.

Although many Upper Canada loyalists were technically fighting the country they were born in, and where most of their families still lived, the war was perpetrated largely by Southern State interests, and it is unlikely many of the American troops were from the New England states which most of the loyalists had left.

The war united English, French and First Nations people of what would later become the Dominion of Canada, in their animosity towards the American invaders, and instigated a distrust of Americans by Canadians that arguably continues to this day.

The next political battle facing the region came in 1837, with the parallel Upper Canada and Lower Canada (Quebec) rebellions. The rebellions were grassroots public uprisings of self-styled ‘Reformers’ against conservative corporate cliques that ran blatantly undemocratic governments in both provinces. These ‘family compacts’ owned and ran the banks, offered special legal protections and monopoly grants to their extremely rich members, fixed elections, made it easier for landlords and creditors to sue struggling farmers, and used the provinces’ military forces to brutally subdue democratic opposition. In that respect the ‘compacts’ bear a close resemblance to the current crony capitalist federal governments of Canada and America – owned lock stock and barrel by the robber barons.

In 1836 the collapse of the similarly-corrupt American banking system had reverberated into Canada, where a massive crop failure added to the worst economic depression in the provinces’ history. The Bank of Upper Canada filed for bankruptcy in 1837 but was rescued by the government of the day at taxpayers’ expense; needless to say, the farmers and the poor received no such rescue.

The Reformers were a disorganized and inarticulate group, led in Upper Canada by William Lyon Mackenzie. The York ‘rebellion’ of 1837 was quickly squelched, and my father, Joshua Pollard Jr, then 24 years old, was one of a contingent that, over three days, snuck Mackenzie out to the west end of the town and hence to his father’s house in Toronto Township, as a result of which he escaped arrest and possible hanging for treason (there was a £1,000 reward for his capture and a significant pursuit force), and fled from there to America.

In 1839 the new Governor General Durham wrote a report on the rebellions recommending the union of the two provinces into a single dominion (ironically, for the purposes of trying to integrate French Lower Canada into a single British nation to extinguish the French culture, and at the same time extinguish the Upper Canada compact’s ruinous debt by accessing Lower Canada’s financial surplus). The Dominion, he proposed, would be run by an elected, responsible, representative government.

The British accepted the union but rejected responsible government. Durham’s report was repudiated by exiled Lower Canada Rebellion leader Papineau, and for the next quarter century attempts at reform continued, finally succeeding when the then-parliament of the united Province of Canada met with the parliaments of the Maritime colonies and agreed on principles of confederation as the Dominion of Canada, which Queen Victoria agreed to three years later, in 1867. I remember the headlines of that day with great pride.

Aside from the short-lived and unsuccessful Fenian Raids of 1866-70, life in Toronto Township has been peaceful for most of the latter part of the century. The rights struggle has moved to Canada’s Western territories, where the new Canadian government has ruthlessly repressed First Nation independence movements. The principal violence plaguing the people of Eastern Canada in this part of the century has been internal ethnic violence, mostly between Catholics and Protestants (and, most bitterly, between the ‘Green’ and ‘Orange’ Irish immigrants), between the English and Irish (the English call the Irish part of Toronto, where, in their view disgracefully, vegetables rather than lawns grow in the front yards, “Cabbagetown”), and between European and Asian immigrants (the latter, desperate enough to work for very low wages and do very dangerous work, are considered threats to the jobs and wages of the former).

Political activity in the 19th century both in Toronto Township and here in the City has centred mainly around meetings in the churches, schools and taverns, often organized and publicized by the area’s newspapers. Next to farming, millwork, and transportation (“teamsters” of horse-drawn wagons), printing of newspapers and ‘broadsheets’ has become one of the biggest employers in Upper Canada in the latter part of the century. Several of the Pollards (including my son Oliver) have come to make their living in the printing business, and seem born to do this work.

Most of our newspapers continue to be politically strident weekly “gazettes” that are more like personal diaries (written often in the first person) than contemporary international newspapers. Initially, our newspapers were largely subsidized government organs, but by the middle of the century printing had became cheap enough to enable an independent press. News from overseas remains slow in coming (and often, and ironically during the War of 1812, dependent on reports in the American papers), so the papers until recently mainly focused on local news, announcements, advertisements and events. The York Gazette was particularly targeted by the invading American troops, and when its offices were burned it did not resume publishing until 1817.

The early papers generally demonized the Americans as vain and dishonourable (some Canadian papers still do), and were essential to recruitment for the War of 1812. The war began a shift in many newspapers’ stance towards Britain from one of adulation to one of criticism (initially for its lack of attention to defending its Canadian colonies, and then, as the century wore on, for its support for the much-loathed family compacts and its resistance to democratic reforms). Mackenzie used his newspaper to win election as Mayor of Toronto (as York had been renamed in 1834) and later to push for the constitutional reforms that were finally realized in 1867.

In the process, the newspapers captured the first sense of what it means to be Canadian, apart from a loyal subject of the mother country. A study of our early newspapers lists the emerging qualities of Canadians, our first non-indigenous national identity myth, as: gallant (now termed as “polite” and still, to many the defining quality of Canadians vis-à-vis Americans), united by adversity (and pretty much unnationalistic in its absence), constantly struggling with natural and imposed hardships (what one writer has termed “the Canadian survival narrative”), and, perhaps surprisingly, exclusionary (of francophones, women, lower classes and First Nations). While the papers lauded the contribution of its First Nations peoples to the War of 1812 effort, once the war was over, the promises that had been made to the First Nations were ignored by both politicians and the press, and almost none of those promises were kept. Discrimination and prejudice by race, class and gender have remained prevalent and accepted in Upper Canada throughout the century.

The Pollards, like many of their neighbours, were Reformers, advocates for responsible, representative government, the abolition of slavery, “free” (paid for by taxes) schools, and separation of church and state. There were about 300 slaves in Upper Canada in the late 18th to early 19th century, most of them “legally” (per the Imperial Act of 1790) brought in by loyalists to do domestic, farm, and artisanal work. The Slave Act of 1793 attempted to end slavery in Upper Canada through attrition: it legislated that no new slaves could be brought into Upper Canada, and although it stipulated that slaves already in the province would remain enslaved until death, children born to female slaves were to be freed at age 25. Slavery was abolished (throughout the British Empire) in 1833.

Between 1830 and 1865, at least 30,000 American slaves escaped to the Canadian provinces via the Underground Railway, many of them coming to Upper Canada. They settled, mostly, in settlements specifically established for them by or with assistance from the governments and churches of the time, and in the larger towns near the border. Even though slavery in the northern American states was illegal for much of this period, those born as slaves in the southern states did not become free by moving to the northern states, whose laws did not apply to them, and they were often pursued by bounty hunters; that’s why so many chose to move to Canada.

It’s hard to say how many of the escapees settled in Toronto Township, since there was so much European immigration and expansion of land grants during this time, and the grants and censuses don’t identify racial origins. But I do recall that that most of the Township’s members supported and encouraged the Underground Railway and the exodus, since many of us are ourselves from refugee families.

4. Work and the Economy

Economic recessions (often called ‘panics’) and depressions have been common throughout the late 18th and 19th centuries; indeed, the economy has been in recession or depression more often than it has not. Here are the major ones to date, with the primary causes in brackets:

- 1789-1793 Recession (counterfeiting)

- 1796-1799 Recession (land speculation, bank insolvency)

- 1802-1804 Recession (end of war, piracy)

- 1807-1810 Depression (trade embargoes)

- 1815-1821 Depression (bank collapses, inflation, high unemployment, market collapses)

- 1822-1826 Recession (market crash)

- 1828-1829 Recession (trade embargo)

- 1833-1838 Depression (bank failures, cotton market collapse)

- 1839-1843 Depression (debt defaults, chronic deflation)

- 1847-1848 Recession (British financial crisis)

- 1853-1854 Recession (high inflation)

- 1857-1858 Recession (insurance failures, railroad stock price collapse)

- 1865-1867 Recession (end of war, chronic deflation)

- 1873-1896 Depression (the “Long Depression”: bank failures, commodity price collapse, chronic deflation, stock market collapse)

Farming in the early part of the century in Toronto Township was, as was mentioned earlier, subsistence, with crops sufficient to provide nutrition for each family and salting, pickling and cold storage to last out the winters. Chickens, sheep, cows, pigs and goats were raised for food, and horses and oxen for labour (horses for human transportation and ploughing, and oxen for stump-removal, dragging timber and operating the sawmills and grist mills).

A growing local population, and the advent of the railway, presented the opportunity to switch to more ‘monoculture’ farming and sell the surplus to provide cash for other purchases that would supposedly allow farmers to live a more affluent and less laborious life. That was the promise, but thanks to the constant economic recessions and depressions, each of which seemingly brought a collapse in farm prices, the abandonment of subsistence agriculture in favour of monocropping and brisk trade has turned out to make farm life more risky, and more exhausting, for most, and no more affluent.

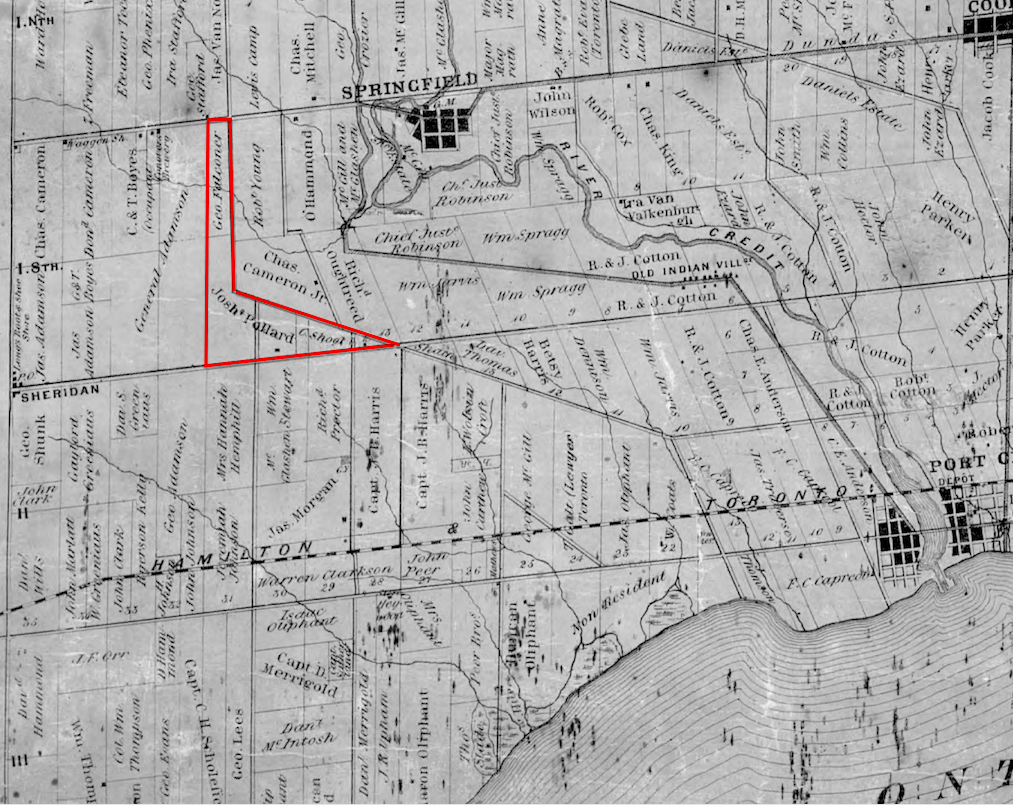

SW Toronto Township in 1859 (Tremaine’s Map). Joshua Pollard Sr’s original 1807 200-acre land grant outlined in red. Its base spanned 4 lots (1 mi), and it was one division (1.25 mi) long. Until the 1830s, all the lands 1 mile either side of the Credit River were reserved for the Mississauga First Nation.

My grandfather applied for an “inn and ale-house” licence when he first moved to the Township, probably with the plan of supplementing his income, especially during the winter months when the farm was dormant, and hedging against bad crop years. It was a good plan, but it wouldn’t be long before Toronto Township had dozens of taverns competing for the drinking-men’s dollar. The combination of too much supply and opposition to the drunkenness and family breakdown that often accompanied the proliferation of taverns, probably made the venture unprofitable, though I recall it continued for more than a half-century.

In 1850, my grandfather died, and the Pollard homestead passed to my father, Joshua Pollard Jr, then 37 years of age (though Joshua Sr’s widow and 3rd wife, then 60, was “provided for” in his will). My father was married to Mariah Hill, a neighbour (most of the first several dozen families to settle in Toronto Township are related by one intermarriage or another, due to low mobility and large family size). At the time of my grandfather’s death, my parents had eight children, aged 1 to 16; I was the second-born and eldest son, then age 14.

Joshua Pollard Jr and Mariah Hill, c. 1860

The 1861 agricultural census shows the following crops grown on our homestead’s 80 cultivated acres that year: 18a (300bu) of fall wheat, 6a (120bu) of spring wheat, 3a (100bu) of barley, 4a (100bu) of peas, 6a (100bu) of oats, 2a (50bu) of Indian corn, 1a (50bu) of potatoes, 6a of pasture, 3a of orchards, and, grown on the remaining land, 50bu of carrots, 2bu of beans, and 25T of hay (for some reason, squash was not included in the census). Our neighbours also grew rye, buckwheat, turnips, beets, hops and clover. An additional 40a was woodlands. Our homestead had 2 horses, 3 dairy and 3 beef cattle, 9 sheep, 4 hogs, a buggy wagon and various saddlery, a lumber sleigh, a grain sleigh, a tanning mill (a horse-powered device, for grinding bark for use in tanning hides) and straw-cutting equipment, and the usual farm implements of the day: plough, spade, hoe, fork, sickle, hook, cradle, roller, flail and rake.

(image: horse-drawn shovel-plough, c.1850s)

(image: horse-drawn shovel-plough, c.1850s)

By this time there were sawmills and grist mills nearby, and in 1854 my father built a second house on the homestead, where we then lived. Some of the farm produce was being sold at the Howes and Pollard Grocery Store and Bootmakers (co-owned by my brother Erastus and brother-in-law Joseph), and the Great Western Railway had begun regular steam train operations in 1855, with a station at Clarkson’s, our neighbours, providing access to markets outside the Township for the grains, dairy products and fruits produced on the homestead. So economic life necessarily became more complex, as subsistence farming became less and less viable for families that wanted to buy the increasingly expensive fabrics, tools and other advantages of modern life that had to be imported.

My father ran the farm for 23 more years until 1873 when, at age 60, he turned it over to my brother, Richard Pollard. My father had done his stint: He’d converted the farm and orchard to viable commercial businesses, won many awards at regional agricultural fairs, directed the local cemetery, and the first school in the area, served 10 years as the area’s postmaster, several years as justice of the peace, and acted as agent for the insurance company offering fire and other insurance policies to our neighbours. He’d just been appointed magistrate for the region. He’d live on the homestead another eight years until his death in 1882.

In 1873, my youngest brother Richard was just 24 years of age and a newlywed. He would rename the homestead operations Maplegrove Farm. As the oldest son I had rights to claim the homestead, but I had the ‘travel bug’ and spent my youth seeing the world. Richard always wanted to be a farmer. His other older brothers made way, starting the great exodus to the cities: Erastus became a merchant in Oakville, James became an engineer and Stephen a physician, both in Toronto. When I settled down at last I too moved to Toronto, and have made my living as a tailor. It was left to Richard to run the farm with my father.

Unfortunately for my brother, from 1873 until just three years ago, all of North America has suffered through the longest and deepest economic depression in our history. The Industrial Revolution may brought staggering wealth to a small elite and to the middle class in some cities, but for farmers, the working class, small towns and immigrants it has brought incredible hardship, and with it, political strife. The Gilded Age robber barons have used their new-found wealth and power to brutally suppress unionization efforts, buy elections and corrupt politicians, and deregulate controls over their monopolistic practices and anti-democratic activities. The widening chasm between rich and poor has led to an explosion of homeless and destitute families, increases in the use of child labour, brutal working hours and conditions for the working class, and the unwinding of equal rights in the American South with the reintroduction of forced segregation and the suppression of minority voting rights.

It has been indeed a dark time for our nation and our people. Let us hope the 20th century, with its new technologies, offers us some respite.

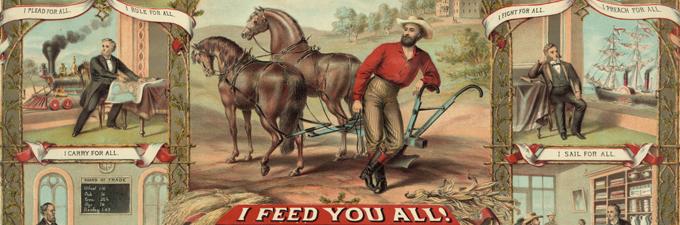

1875 agricultural newspaper cartoon protests the wealth and arrogance of the urban robber barons and their political and legal allies

My brother Richard, the third generation to farm the Pollard homestead in Toronto Township, finally gave up and sold the homestead to the Shooks, our neighbours, just a few years ago in 1891, for a very small sum, since farmers everywhere were suffering from the Long Depression. Like many of our family members and neighbours, he too has moved to Toronto and, now in his 40s, has begun working as a motorman and conductor for the city railway (which has just been converted from horse-drawn to electric-powered trams – the electricity is created from our new coal-fired plants). Some of Richard’s children and our cousins also work for the railways, which are, alas, still unaffordable for the poor.

While the bicycle has finally (in the past five years) been engineered to be safe and efficient (I can’t understand why it took so long), it has really never caught on as an effective means of transportation for the poor and working class in Canada. Now that it’s become affordable to most citizens, the new passion for the automobile has begun, and our new road networks seem to be being developed with the automobile driver’s needs in mind, not those of the cyclist. In Europe, by contrast, I understand the bicycle is playing a major role in the emancipation of women, finally allowing them a means of traveling alone to places beyond normal walking distance.

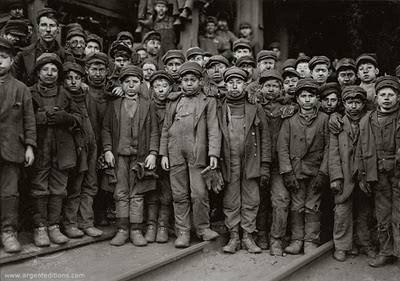

Some of my nieces and nephews are worked in the growing but low-paying garment industry of Toronto, or in factories producing a growing range of industrial products. Hired domestic work, and dangerous work (mining especially), continues to be mostly done by newer immigrants from poorer European countries and from Asia.

(image: urban child labourers c. 1880)

(image: urban child labourers c. 1880)

The world has been much changed by the advent of the age of mechanization, the engine, and coal. Recently, in 1885, so much of our planet’s forests had been harvested, including over 90% of the primeval forest in Toronto Township and the rest of Peel County, that of necessity coal surpassed wood as the world’s, and the Province’s, top energy resource. We are stripping the world of its forests, the canopies beneath which all other life lives, until there is nothing left but sticks, and I fear we may do the same with coal, which also, when used to excess, hurts our lungs and poisons our air. What will we do when we run out of coal?

This new Gilded Age of robber barons, and the resulting gulf between rich and poor, has ushered in a huge shift of people, wealth and influence from country to city. It is a replaying of the struggle over inequality of the era of the family compacts a half century earlier. When will we learn that every time there is a jump in inequality of wealth, income and opportunity, every time we allow the economic dominance of corporations and the idle rich and crony capitalism, and see as a consequence the disappearance of the middle class, the result is suffering, violence and war? When will we learn the lessons of history?

5. Home Life: Education, Religion, Play, and Community

Even at the start of the 19th century, there was strong support for elementary (up to sixth grade) community education, and in Toronto Township the first school, called simply the Red Schoolhouse, was established in 1816, with my grandfather as one of the founding trustees (my father also served as Director). Land for the Schoolhouse and Meeting House was leased from the neighbours across the Middle Road from our homestead. Tuition was provided in the form of firewood to heat the school. Schooling beyond 6th grade was rare in those days, and considered unnecessary for the life of a farmer or farmer’s wife. It was a simple and spare life, but it was sufficient, and remarkably egalitarian.

Prior to the 1850s, church ministers would do a weekly or fortnightly circuit of the entire area from Toronto Township to Wellington, staying at designated homes after each service. The largest service in the area, on Sunday mornings, was a multi-denominational one at the Red Schoolhouse, and the Schoolhouse served as a major social meeting place as well (the ministers of the time brought news from other families on their route). Four churches were built in the area around mid-century, when I was a young adult, but even after that the Red Schoolhouse continued to serve as a major multi-denominational church, and was sufficiently popular that it subsidized some other area Methodist churches until very recently. It was there, and from the people of our community, that I learned everything I know of value.

The Pollard and neighbouring Shook families two years ago in 1897, taken on the Pollard homestead now owned by the Shooks. That’s me, Theo Pollard (standing third from right) and my wife Hannah Shook (seated, second from right). Many of the trousers, jackets and frocks are my handiwork.

Schoolchildren for much of the century were expected to observe the work activities of their older siblings, but not work until they had completed grade 6, after which they were assigned household and light farm duties such as feeding the chickens. Around age 17, they took on full household and farm duties, with the young men assigned the heavy work and the young women the jobs requiring more coordination. The oldest son in each family (I am a rare exception) was generally expected to work there for life, and inherit the farm on his father’s death; the young women and the younger males were expected to marry, move out and start their own families by their mid-twenties.

With the shift of life from the country to the city, much has changed, but not, I’m afraid, for the better. Education is now compulsory to grade 6 (age 12) but the growing disparity between rich and poor has meant that many boys of age 12 and many girls of age 14 (and even younger, in defiance of the law) are now working making textiles, and in the mills and mines, which is much more severe and dangerous work than that their country counterparts did a few decades earlier on the farms. Laws to prohibit child labour have failed, largely due to deference to rich corporate interests but also because desperate working class parents say they need the children’s income to feed their families.

In my grandfather’s time, outside of church services, social activities included occasional dances, essential to enabling young men and women to find marriage partners, and visits, often to exchange goods and services, that, because of the distances involved (often on foot, occasionally on horseback), frequently involved overnight stays. Such visits were quaintly called “tarrying”.

Now, in the city, the pace of life does not accommodate much “tarrying”, and, while working hours remain long (sixty hours a week is not unusual), the drudgery and unhealthiness of the work many do is not good for the body or soul. Sixty hours of work outdoors on a farm is wearying but uplifting – you see the results and they are yours. But sixty hours in a crowded, enclosed, polluted factory or coal mine in labour for someone else, where you see none of the final products of your work, is a prescription for madness.

On the farm, in the old days, children’s play often revolved around mimicking the activities of adults. Some children played “school”, with the older children taking the role of teachers; others, like my siblings and me (described by neighbouring parents in their diaries as “gayer” than our peers), preferred to play “going to a dance”. By contrast today, there seems no time for child’s play anymore, and what there is seems prescribed and constrained by rules and regulations, and leaves nothing to the child’s imagination.

One thing that hasn’t changed is the seeming randomness of the diseases that take our loved ones. My brother Stephen the physician tells me that about half of the settlers in the early 19th century died from tuberculosis, pneumonia, influenza, other infectious diseases or bacterial infections of the digestive system. About one in four children died young, one in eight women died of complications of pregnancy or childbirth, and not a few died of farm accidents or complications thereof. But for those who avoided these, life expectancy was remarkably long – most often into their 80s or even 90s.

And nearly a century later we remain victim to these terrible diseases and ‘complications’, none the wiser for all we have learned about them, and only the frequency of infant and childbirth deaths has declined. For those who live to adulthood, the same proportion live to their 80s as did so a century earlier.

Grey building is 209 Brock St, Toronto — my home.

I try to avoid nostalgia, but when Hannah and I sit and talk in the evenings, it’s often to remember the incredible sense of community we had eighty or even fifty years ago, and how much of that seems to have been lost. We were just a couple of dozen families, farmers all, struggling together in a beautiful but challenging place we had all chosen to move to. Even now, a century later, the same names appear on the maps of Toronto Township, names of people we worked and played with and loved – the Shooks, the Oliphants, the Westervelts, the Merigolds, the Hammonds, the Adamsons, the Greeniauses, the Hemphills, the Oughtreds, the Harrises, the Clarksons, the Camerons. And, in my father’s and grandfather’s generation, before we drove them all away, our Mississauga First Nations families as well.

We knew, and still know, all these families. We proved up our land together, built houses together, created schools together, ploughed fields together, fought together, prayed together, rebuilt together after disasters, mourned and buried our dead together. As children we played together, as did our parents when they were children. In many cases we married each other. We loved each other as much as we loved the members of our own blood families.

How have we lost that sense of community? I think it’s the economy that’s mainly the cause, an economy that once was based in sufficiency and cooperation but now is based in greed and waste and efficiency and destruction and violence and separation from the land. Where did we go wrong?

Three of our children live in cities far away – too far to travel. We can’t blame them – there’s no living to be made in farming anymore, or in tailoring for that matter. Oliver has moved to Winnipeg, hoping to make his fortune in printing and publishing. His sister Mary moved there too. Frank is a barber, still in Toronto, but he’s actually made his wealth as a bookie – preying, I think, on the desperate hopes of the poor. Clara’s in Montreal, a stenographer with a small baby.

I used to think it was our manifest destiny to prosper through hard work, and that that destiny was open to all. But now I’m not so sure. All the suffering, the cruelty, the wars that seem to get ever more violent and global, the mental distress, the abuse of women and children! How can I believe in the myth of ‘progress’ – that the world is generally getting better, and that with hard work and devotion our life and our descendants’ will be ever more so?

Perhaps, instead, the world is prescribed, fated. Perhaps whatever will be is God’s will and not to be questioned or complained about – or predicted or planned for. I think we all live lives of considerable self-sacrifice, but it isn’t for our children or out of some belief it is our duty to God or nation. It is, rather, the only life we know, and now, I fear, the only one we can imagine.

I hope some day one of my descendants writes the story of the Pollards and their communities in the 20th century, and that it’s a more peaceful, prosperous and joyful story than this one. One in which we rediscover the land and with it our connection to all people and all the beasts of the earth. And one in which a sharing and equal community once again is the font of our lives, our purpose, our compass. And that this abundance we have (though unfairly shared) – all this! – is, at last, sufficient.

You are so lucky to have your great grandfathers diary. We are doing my family’s genealogy and would love to have personal details and understanding like this. We always say we don’t understand the Why of people’s decisions when we are dealing with dates and birth certificates etc. Why people did things like, sell the farm, or move to another country. Understanding the why allows us to know and connect with human motive over the centuries.