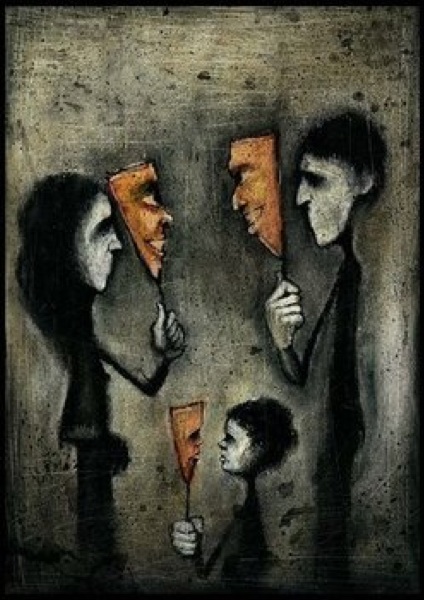

image from Nick Smith’s friend John Wareham’s collection

This essay, like all essays, is a story. It’s my own patterning of what I’ve perceived, intuited, thought about and felt, and then recalled in an effort to make sense of it all. In the case of this particular essay, there is no empirical evidence of its veracity. In fact, it’s evidently not true. But it’s my story anyway, at least for now. Here it is, in all its apparent truthlessness:

Every story is an invention. If enough people hear it and believe it to be true — if it fits with their worldview i.e. the collection of other stories they have come to accept as true — it becomes a myth. A myth is not necessarily false; it’s just a story sufficiently widely accepted that people act as if it were true and are hesitant to challenge it. At this point it might as well be true, because anyone who denies it is likely to be, at best, ignored. Like all stories, myths are just simplifications, attempts to see meaningful and reliable patterns in the firehose of sensory and cognitive messages we are all bombarded with.

Every story is a lie. Not (usually) a deliberate one, of course. Most stories are invented with the best of intentions — they seem to make sense, and to be useful. They seem to fit with our other stories. But reality is unfathomably more complex than any story can ever tell. What we believe we perceive with our five senses and our dim brains is just an insignificantly tiny, filtered, incomplete and imprecise representation of all-that-is. Other creatures perceive the world very differently, and their stories of reality are utterly different from ours.

All stories are absurd oversimplifications, pale representations of the truth, sketches of what little our impoverished senses are able to pick up, that our muddled brains then fashion into models of reality. We do the best we can, but we have absolutely no idea what reality is. We cannot possibly know. The tools evolution has equipped us with only show us enough partial glimpses of reality to optimize our chances of survival without overwhelming us. So we make do with our stories, our sad representations, and in telling them to ourselves and each other often enough come to believe not only that they are accurate representations of reality, but that they are reality. We come not only to see our stories as reality in our minds, but to embody them with our apparently-separate whole being.

Behind every story is an attempt to rationalize what is happening. What is happening has nothing to do with ‘us’, these conjured-up ideas of separate, volitional selves. What is happening, what we seem to be deciding to believe and do, is the only thing that could have happened. ‘We’ act, seemingly with volition, and then our minds attempt to rationalize our behaviour, make it fit with what we believe we believe, what we believe motivates us. Our evolved minds are doing their best to help us, to make sense for us. But they actually are of no help at all.

It’s as if we are desperately playing along with a joke that we don’t understand, so that we don’t appear foolish for not getting it, for not expertly going along with it. It’s all a mad attempt to make sense of reality and truths that can never be made sense of, because we can’t possibly understand them, because we are trying to understand them from a perspective (that of the apparent volitional separate self) that is, like other stories, a complete fiction. Reality does not and cannot, to the separate, limited self, ever ‘make sense’.

Here is a partial catalogue of human stories:

- What apparently was: histories and recountings and gossip and tales and reports

- What apparently is: perceptions and conceptions and beliefs and worldviews and identities and selves

- What could be: hopes and dreams and imaginings

- What apparently happened: rationalizations and judgements

- What allegedly happened: news and documentaries and essays and non-fiction (in all forms and media)

- What might have been or might be: fiction and fantasy (in our heads and in all forms of media)

- Why/how things apparently happened: models and theories and science and teaching

- Art in all its forms: art re-presents all kinds of stories, meandering freely among all seven of the above types of story

So there is this blizzard of stories, those compiled and stored in a hopeless jumble in our heads and many more bombarding our senses. The pattern-sense-making that is the story of you is buffeted by trillions of other stories, the stories of other people, their pattern-sense-making, all of the stuff in the catalogue above and more. People telling you to listen to their story, to believe it instead of the story you already believe, to become that story instead of the story of you. And sometimes you will do so.

All of these stories are fictions, made-up imaginings, attempts to assemble a coherent whole from the tiny fraction of reality we can even begin to fathom. At one stage, a few of these stories might have seemed to have been useful, might seem to have helped us cope or get something apparently accomplished in the short run. They seemed to confer some evolutionary advantage. But even the appearance of accomplishment is just another story.

‘What seemingly happened’ was actually the only thing that could have happened, and it happened to no ‘one’, no separate ‘person’, and it was in any case just another story. There is actually no time within which anything can happen, can be ‘accomplished’. We just piece the results of our patterning, our sense-making, together by inventing time as a matrix, and then we fit what seemingly happened into it, to try to make sense of it. Our minds are good at such inventions, and it is all they can do to try to make sense of ‘what seemingly happened’.

But there is no sense to ‘what seemingly happened’, no purpose. And a little voice inside us whispers to us that something is not quite right with all these stories we want to believe, but we don’t know what it is. We have no other way of making sense. So we’re always unhappy, always searching, trying to make the ‘story of us’ turn out, somehow, a little better. We are perhaps intuitively seeking the wholeness that the accidental emergence of the separate self inadvertently destroyed.

You may say this story does not make any sense. And it doesn’t, it cannot. It’s just another oversimplified raid on the unknowable. But unlike most stories it might just point to something that is not a story. It might point to an intuition, a remembering, of what it was and is to be not-separate, to just be, indistinguishable from all-that-is. But since we lack any knowledge of how ‘we’, somehow, got separated, or how to get back home, ‘we’ are inclined not to listen to this little voice, and its annoying intuition that all our stories (including the story of us) are untrue, and that what is actually real is outside and before our apparently separate selves, that what is actually real is only and entirely and always all-that-is (paradoxically including all our stories). That not only is ‘all-that-is’ real, independent of any observer, but that there is no observer. There is only, unfathomably, all-that-is.

There had to be a story of you before there could be any of the other stories in the above catalogue. The story of the volitional separate you was an evolution, an adaptation or exaptation, a random variation tested out by Gaia to see if it might ‘fit’ better than what was there before the story. There is some evidence that something of the story of self exists in all creatures in brief times of stress. They see their ‘selves’ as a somewhat horrifying illusion that nevertheless enables them to escape from some acute crisis through fighting or fleeing or freezing. Gaia is merciful to those whose existential threats are rare and fleeting — she invokes the ghastly sense of self in such creatures only as long as the threat lasts, and then enables them to shake it off, as the nightmare it was.

For those of us who live in constant stress, however, we ‘smart’ domesticated creatures, the ghastly story of the volitional self endures until it overcomes us, until it becomes us. For us, the wonderful adaptation of the temporarily separate self becomes a horrific maladaptation, an eternal nightmare, a lifelong prison.

This is just another story, and a particularly useless and frustrating one, one that cannot be ‘realized’. Why then am I so attracted to it? In those rare astonishing moments when I seem to fall away and remember what it was like to just be, without story, what is happening?

When I watch the birds, I can sense that they are free from the horrible affliction of stories. They are not selves, they just are. They exist in the world raw, not sheathed inside the false protection of the illusory self. They have no illusion that anything can be other than the way it is. They have no illusion that they exist apart, or that ‘they’ will die. They are much wiser and freer than I, burdened with this self and these terrible stories, can ever be.

What a splendid elucidation! I really love your writing on the non dual…it’s been very opening for “me”. In those rare astonishing moments when I seem to fall away and remember what it was like to just be, without story, a voice whispers within…this is it! Ahhhhh. Thank you Dave.

Disenthralling.

Thanks both of you, and to those who read and commented on this on FB.

“anything can be other than the way it is”. Maybe so. Not possible to change what is. But if that truth stops us from making choices about what we do in the next moment, what is the point in being human? Or are you saying when we think we’re making a choice that’s an illusion?

Yes. Studies of brain waves show that we have already made the choice and started to act before the neurons that ‘record’ that decision ‘make the connection’. They are rationalizing the decision, not making it. We just want to believe we have control, because it makes life less scary and more ‘meaningful’. There is no point to being human, no point or meaning or purpose to life, but why do we need one? Life is just so amaaaazing just as it is.

Good to read someone thinking directly, even if prolix, in response to the overwhelming buy-in of the popular consciousness to the notion that “stories are how we think,” “changing stories will change how we act in the world,” and so on. Well, yes, if we are deluded into confusing mental concepts about reality with its direct experience, “mixing real for fake, ideas for the mystery,” and acting as though the perceptual filters that “stories” put in front our senses were benign or even illuminating. The query underlying your prose is, if there is no self, who does the experiencing? The Buddhist response, from the Heart Sutra, is that the thought does the thinking, the sight does the seeing, and sensation feels itself, the consciousness is aware of itself, and so on, none of them giving evidence of a continuity of self, one that does not arise and pass away in each moment.