If you are a student of complexity theory, and of philosophy, you can quickly arrive at a place of great cognitive dissonance: On the one hand, our culture is driving us, for quite compelling reasons, to take actions that make things better for the rest of the world, and to “self-improve” — to change our own unhealthy and destructive behaviours. But on the other hand, some of us have come to believe, intellectually at least, (1) that our personal actions will have no discernible sustained impact on the rest of the world (complex systems tend to self-perpetuate and to counter the effects of even the most persistent and well-conceived interventions), and (2) that we have no free will, agency or choice in what we do in any case — rather than making decisions, the brain/mind/self is merely rationalizing decisions that have already been ‘made’ and started to act upon by the conditioned creatures ‘we’ presume to inhabit and control.

The former dilemma — that we feel driven to make the world better through personal actions even though we may know in our hearts that that won’t make any enduring difference — has been hashed over a lot in activist circles. The argument is that we have to try anyway; that it’s in our nature. Direct action certainly seems to make a small difference, at least for a while, so why not (protest local polluting projects and entities, clean up a river, blockade a destructive development etc)? It’s not our business to worry about what will happen when we’re gone, or what is happening beyond our sphere of influence. Though we may be by nature preoccupied with the needs and imperatives of the moment, still we do our best. It’s both enough and necessarily to try, even when it may be, in the longer and broader context, hopeless.

The latter dilemma — that we feel an obligation to “improve ourselves” through personal behaviour change, even though some of us have come to ‘know’ intellectually we have no real agency over what we do or do not do — is the subject of this essay.

The question here is not whether our behaviour changes or not; it’s about whether personal volition plays any role in that change, or whether, given our conditioning and the events and options presenting themselves moment-to-moment, what we do, or don’t do, in each moment, is the only thing we could possibly have done, and therefore all the angst and anguish we have about our decisions is pointless, and changes nothing.

That’s not to say that we can rid ourselves of this needless angst and anguish — it’s just one more thing we have no agency over. In the long run, the human mind seems compelled to be unhappy with the apparent sub-optimality of ‘its’ decisions, and with the apparent unfairness of its situation. Hindsight is perfect, and nothing can ever match the ideals we can imagine — not for very long anyway.

You may find this preposterous — we certainly seem to have personal volition over what we do. It’s a paradox, and in that sense it is preposterous. But bear with me for a few moments.

Over the years this blog has recommended a process called “self-management” for taking charge of your own situation, informing yourself with personally-collected data, and acting in accordance, in a number of situations:

- Managing your own health and fitness: I used statistical analysis to identify what treatments seemed to work best for my body when it was coping with debilitating ulcerative colitis. And annually I review, plot and analyze the data from a comprehensive blood test (here in BC you are able to access your health records and test results personally online). Possibly as a result of that, I am now 10 years symptom-free.

- Making healthy/helpful behaviours easier and/or more fun: Pollard’s Law of Human Behaviour asserts that we do what we must (our personal imperatives of the moment) and then we do what’s easy and/or fun; there is never time left for what is ‘merely’ important. So I made exercising easier and less tedious by investing in a treadmill desk that allows me to multi-task (reading, writing, watching videos) while working out. Even my upper-body and core workouts with weights are done while listening to podcasts I particularly enjoy. For the first time in my life, my exercise is done regularly, and it’s something I actually look forward to. My long history of maintaining my times for 5k and 10k runs over the past 40 years (sometimes being a data geek really is useful), adjusted for the inevitable slowdowns that come with age, also enables me to know in advance when I’m getting sick (my times go well over the regression line) and to take steps to heal.

- Eating better: While the statistical analysis referred to above had already helped me improve my diet, I have more recently shifted further to a whole-plant based diet (persuaded by the science of nutritionfacts.org) with less salt, less sugar (especially processed sugar), less fat (especially saturated fat) and less processed food in general. This was at least as challenging as going vegetarian and then vegan had been years ago, since I really do like salt, sweets and oils, and I am generally a lazy chef. But I’ve managed to make the changes, again by making it relatively easy:

- a meal a day of varied raw veggies and salad stuff with a tasty low-fat dip takes little preparation or clean-up

- fruit and veggie smoothies

- keeping useful ingredients like turmeric and ground flax seeds handy and adding them liberally to meals

- keeping a pill-pack of B12 and D3 vitamins so it’s easy to remember to take them regularly, and

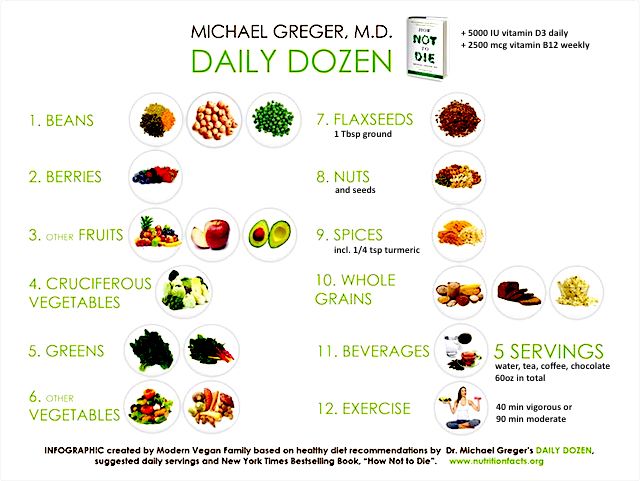

- finding several one-pot, 5-or-less (but variable) ingredient, 20-minutes-or-less prep time recipes that fulfil my “daily dozen” (see graphic above)

Taken together, these discoveries have made it easy and even enjoyable to eat healthier.

- Increased self-awareness of stress: I’ve learned that I can’t avoid stress in my life; nor can I avoid the anxiety that arises in me because of it. But I’ve learned to become aware of when I am getting reactive to a situation (bad weather, vexatious people, a loved one’s distress etc). Just being self-aware helps, though it doesn’t eliminate the reactivity. I have a list in my wallet of the things that I know trigger anxiety, fear, distress, shame, anger and sorrow in me, and recognizing the trigger reaction (it helps that those I love know the symptoms and point it out to me as well) seems to be enough to bring some perspective and at least lessen any overreactions.

- Reducing personal environmental impact: Over the past year, by monitoring my daily household energy consumption, informing myself about opportunities for reducing consumption, and tracking consumption against temperature (my heat is electric), I’ve reduced my electricity consumption by 40%, effortlessly. I didn’t think such savings were possible without discomfort and inconvenience, but the data made me do it!

So there have been changes, for the better, in my personal behaviours, apparently as a result of this “self-management” process. What’s going on here? If I have no free will, agency, control or choice over my actions, how did these changes come about?

My guess is that they were inevitable. By nature I’m a data collector. I’m curious and imaginative about trying new low-risk things, and that’s led to me being an avid reader of books on health and self-management. I’m averse to pain and suffering so I was really motivated to do the statistical analysis to manage the colitis. While I hate exercising, I’m vain about my appearance, and that, along with the personal, statistically verified health benefits (less illness, less pain, more resilience) made it inevitable that once I found an easy way to exercise, I’d do so. And the people I love showed me, by example, how a higher level of self-awareness reduces their reactivity and hence their stress, anxiety and suffering, so it’s only natural that I would over time pick up this skill from them and apply it to my own life.

No free will was really involved. If you had been watching me over the past ten years from a distance, and could see inside my head, these self-improvements would have seemed inevitable, given my basic nature and the circumstances that I was presented with over that time. I really had no control over, and no say in the matter. There are probably other apparent ‘self-improvements’ that didn’t happen to me, because they weren’t in my nature, or because the right circumstances didn’t present themselves. If I hadn’t met the people, or read the books (all happy accidents) that have influenced me so much, my life would probably have unfolded very differently.

So if it’s all dependent on our inherent or enculturated nature, and on the circumstances that arise in our lives, and we have no control over either, what’s the point of talking about any of this? Or more broadly, what’s the point in aspiring to any ‘self-improvement’ whatsoever?

The following could perhaps be a circular argument, or an oxymoron, but it seems possible to me that if it’s in your nature to experiment, and to want to learn, there are two things you might be able to do to increase the probability that the circumstances that arise will be more auspicious towards the changes you are hoping for than they would be otherwise:

The first of these is to learn more — about yourself, about your body, your health, your nature, what motivates you, what (perhaps for reasons buried in your past) triggers unreasonable and unhealthy reactions in you etc. Better self-knowledge would seem to open you to possibilities that otherwise might not arise. For example, knowing that a chronic physical or emotional illness is inflamed by something in your diet (or something missing from your diet) would seem to make it more likely that you would change that diet, even if you might not be that excited about the change. Or, if you discovered that walking an hour a day on a treadmill would reduce your risk of heart disease by 75% (helped by personal blood test data showing improvements in LDL cholesterol etc), it might be more likely that you would take up and stick with a regular walking regime.

It could of course be argued that we are either curious enough by nature (and fortunate enough to have the time and capacity) to learn, or we aren’t, and that therefore there is no free will involved in this either. If you’re going to stumble on this article and find it useful and act on it in some way, that is all because of some combination of your inherent or enculturated nature and happenstance — no free will or agency involved.

It’s said that people who seem exceptionally lucky make their own luck. That’s perhaps saying the same thing — we don’t make choices; it’s either in our nature to learn and try things that increase the likelihood of good fortune befalling us, or it isn’t.

That brings me to the second thing we might be able to do with some degree of volition to increase the probability that the circumstances that arise will be more auspicious towards the changes we are hoping for than they would be otherwise: to make space for a change of behaviour — to open up the possibility for it.

How might we do this? Again, I think it comes back to self-awareness. If we’re aware of what motivates us, of our propensity for certain behaviours, and about our inherent nature (curious, courageous, persevering etc, or not) and our enculturated nature (to be defensive, to procrastinate, to judge people in certain ways etc, or not), then perhaps we can use this self-awareness to create opportunities for us to act in ways that are better for ourselves and those around us.

Complexity theorists argue that while human-scale interventions will have little or no impact on a complex system (which is inherently unknowable and unpredictable), it may be possible to influence the initial conditions of a small system in its early stages before it becomes ‘unmanageable’. So for example, ensuring that we get enough sleep might affect us in all kinds of positive ways. Putting a list like the graphic above on our refrigerator door might cause the uncontrollable creatures we believe we inhabit to engage in slightly more healthy eating behaviours (or to tear down the list and throw it away, depending on our nature).

This could also be a circular argument. Perhaps it’s either in our nature to get enough sleep or not, and to maintain and use lists, or not, and we’re just fooling ourselves believing that the apparent ‘decision’ to go to bed earlier or to post the list or to change what we eat depending on what the list suggests, would be any different without the intention or the list. It’s probably impossible to know.

All I do know is that ‘self-management’ seems to be in my nature, though it’s only very recently that I’ve begun to use it, and reaped the astonishing benefits it’s given me. If we see our lives as a play, with all the parts already written (though not given to us more than a line or two in advance of us acting them out), then agency, self-control, self-management, volition, free will and choice had nothing to do with me being, and becoming, such an incredibly blessed agnostic. Hard, but not impossible, to believe.

No wonder then I am increasingly averse to giving advice, and more and more inclined to just tell my own rather tedious and ordinary story, mostly so I can get (as my nature drives me to seek) the gist of how the plot seems to be unfolding. No wonder I am increasingly silent, here on this blog and in my interactions with the world. If there is no free will, then freedom, it would seem, must lie in some other, possibly unknowable, unimaginable place.

It was forbidden.

It could not be avoided.

The observing system looked at any construction from outside and

Remade it anew.

The building was never completed.

Eternity did not submit to construction.

There was no exit except in silence.

— L.H. Kauffman: What is a number? Cyb.&Sys(1999)30:113-.

(Text only available at http://www.math.uic.edu/~kauffman/NUM.html )

Dave

I do believe you are going down some profoundly wrong forks in the road. But I ask your indulgence to examine the behavior of children in order to understand why I think some wrong forks are being chosen. The story of the children and the experiments is in The Secret Life of the Mind: How Our Brain Thinks, Feels, and Decides, by the neuroscientist Mariano Sigman.

On page 228, Sigman begins a section titled The Teaching Instinct. I’m not going to try to describe all the experiments here. Suffice to say that children who cannot speak will uniformly try to teach something they know to others who might benefit from the knowledge. Without exception, the child doing the teaching will stand up, if they have been sitting down, when they begin to teach. The children expertly use Ostensive gestures: engaging the other person with eyes and body; using the student’s name; lifting eyebrows and changing tone of voice. Even the congenitally blind use these gestures without ever being taught them. Ostensive gestures are effective the day we are born. ‘When we tell babies without ostension that an object is a pencil, they understand it as a description of a particular object. Yet when we say the same thing with ostensive cues, they grasp that this explanation refers to a whole class of things…’

If you read the book, you will find half a dozen pages of description of various experiments with children, including some where the children conclude that the adults are too stupid to be taught. You will also learn that humans effortlessly use pointing while teaching…something monkeys cannot do.

So, I suggest that your attempt to walk away from teaching is an attempt to behave in a way that is not consistent with human nature. I don’t say it’s wrong, as I know you are quite committed to your ideas about radical non-dualism and the lack of free will. But you might wish to study these experiments as, perhaps, a cautionary tale.

Don Stewart

For me decision ist a misty mixture. Words veil the fuzzy character of a situation.

I opt for one tiny fraction of billions of possibilities. Not a nice feeling… A feeling of powerlessness. So uneasy for humans… feels like drifty or sticky or reeky. No control. But influence.