It’s been a while since I’ve written on this blog about a real ‘aha!’ moment. Thanks to Kate Raworth, I just had one.

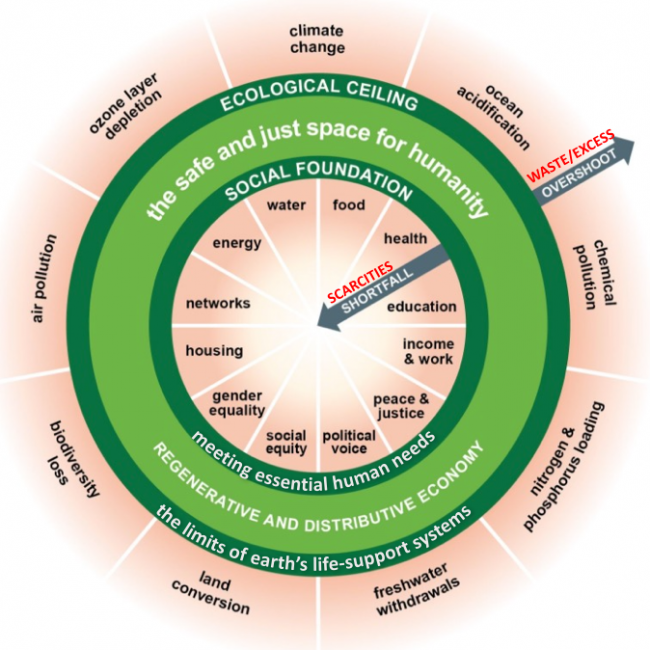

Kate is the author of The Doughnut Economy, an astonishingly simple economic model that captures our current predicament, and the inadequacy of the current economy, perfectly. It’s illustrated in the diagram above, and explained in this one-minute animation, the full text of which is as follows:

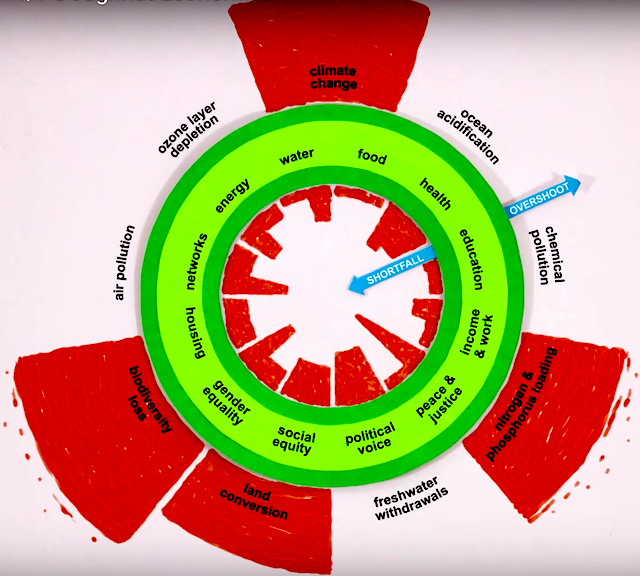

In the 20th century, economics lost its purpose, and started chasing the false goal of GDP growth, pushing us to deepening inequality, and pushing us all towards ecological collapse. This century calls for a new goal: meeting the needs of all, within the means of the planet. It’s time to get into the doughnut: the sweet spot for humanity [green area of the diagram below]. But that’s no easy task: Today billions of people still fall short of their daily needs, from food, housing and energy to health care and education, and yet we’ve already overshot our capacity in some of earth’s most critical life support systems, driving climate change and the breakdown of biodiversity [red areas of the diagram].

What we do in the next 50 years will shape the next 10,000. So let’s replace that last-century goal of endless growth with the goal of thriving in balance, and if we’re to have half a chance of getting there, what economic mindset will be fit for the task?

As for any predicament, this one has no solutions, only adaptations and coping mechanisms. Our technology-fuelled capitalist, industrial-growth economy only encourages overshoot. But this economy is the evolving result of the actions of billions of people: No small group created this economy, no one is to blame for it, and no group has the power to change or replace it. We just have to acknowledge its reality, and its inevitable collapse, and adapt ourselves to its unfolding as best we can.

That doesn’t mean doing nothing. Kate’s website has many ideas on how to deal with the apparent Hobson’s choice of reducing overshoot by eliminating growth at the global scale (hence increasing inequality, scarcity and suffering for most), or reducing inequality, scarcity and suffering by accelerating even more quickly towards economic collapse. In our current economy, we can’t do both. But in small ways we can (and must) reduce both scarcities and overshoot, even if our actions are unrecognized and merely what Joanna Macy has called “holding actions”. Even if we will have no idea whether they did any good.

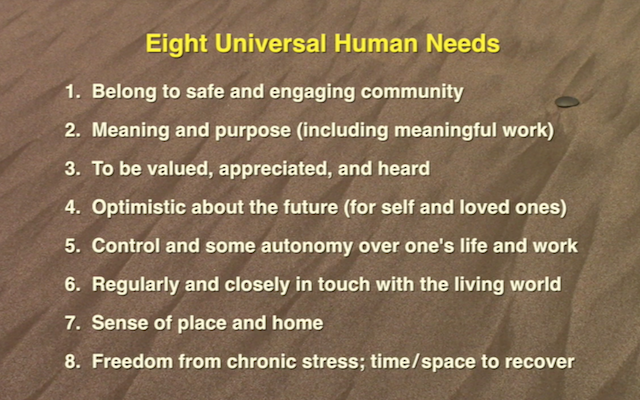

We could quibble about which essential human needs belong in the inner circle of the diagram (Michael Dowd’s new video based in part on one of my articles summarizes what I think are eight essential human needs that deserve a place in this centre circle):

And we could quibble about the dimensions of overshoot in the outer circle. But what is important, I think, is that we start to think of human activity as a balancing act, the ultimately impossible task of reducing the red areas in both the inner and outer circles, so that we ultimately live at least a bit more in “the safe and just space for humanity”. In other words, we must learn to live within our means, as we did brilliantly during the first million (“prehistoric”) years of our time on earth.

The chart also shows that we don’t have to worry about other creatures in striving to do this. It’s hubris to think that we are responsible for stewarding this planet. If we take care not to be in overshoot (and when we are no longer around), the rest of life on earth will take care of itself, as it has always done.

Another feature of this model is that it clarifies the role that human overpopulation plays. The more humans on this planet, the more potential shortfall/scarcity we create trying to accommodate them, and the greater the risk of overshoot in doing so. Population is the denominator in the equation, but it is not the only cause of overshoot, and not the only thing we must reign in to reduce it. Waste, inequality, and the vast inefficiencies of scale that globalization (in its well-intended but ill-conceived attempt to reproduce first world wealth) contribute much more to both the inner and outer red areas on the diagram, than raw human numbers.

Finally, this amazing and simple model really presents a blueprint for what any proposed Green New Deal must try to accomplish. Their goals are the same.

So as a joyful pessimist, a student of our culture, and as a collapsnik, I love this new model. We cannot prevent collapse, but this model shows us what we did wrong, and what we continue to do wrong, and how we can at least moderate some of the most devastating effects of our economy and human activity, before collapse makes all our efforts moot. It is a predicament, and as such it is far too late to “get the red out” and restore our economy and ecology to health and balance. But at least, and at last, this gives us a picture, and a useful, meaningful scorecard, as our civilization enters its final decades, to chronicle its, and our, demise, and our attempts to reduce and undo what cannot be undone.

Thanks to Jae Mather for pointing me to David Suzuki’s reference to this model, to the Rockstrom team who developed the first iteration of the model, and to Kate for saying so eloquently what should always have been obvious.

Yes Dave, we have a deep psychological need to dream up ever more rationalizing bullshit to structure our remaining time, while we stumble on to the place where all the bullshit comes to an end.