Dave Snowden’s Cynefin Framework

This is a bit of a screed against really bad “strategic” plans, which is to say most of the documents that go by that name. Most written plans these days are means to achieve a particular set of objectives, and most of those objectives have to do with complex situations. If the situation or problem were merely complicated, anyone with appropriate training and basic analytical skills could solve it; there would be no need for an involved plan.

Whether it’s an organizational goal (like coping with CoVid-19 or with a competitive threat), a social one (like combatting racism), an economic one (like reducing inequality), or an ecological one (like dealing with climate collapse), chances are it’s about dealing with complex predicaments, not (merely) complicated problems.

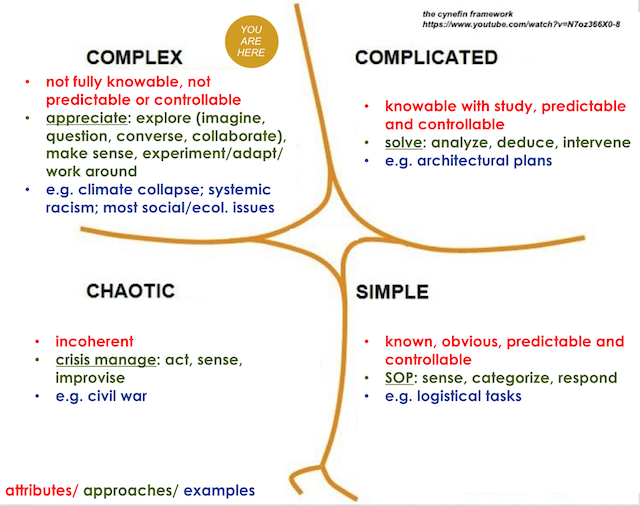

As I’ve explained in my “Complexity 101” posts, the difference is night and day. As the Cynefin chart above shows (Cynefin, pronounced “kuh-nev’-in”, is a wonderful Welsh word that means something like “the place from which your identity and understanding arises”), complicated problems can be analyzed methodically and pretty-much solved, such as in the design and construction of a building. A complex predicament on the other hand can never be fully or even thoroughly understood — there are too many variables at work — so the best that can be hoped for in addressing it is a collective appreciation of it and some ideas to accommodate, adapt to and/or work around it.

That doesn’t mean that dealing with that competitive threat (or other complex, dynamic socio-economic or ecological challenge) is hopeless. It just means there is no way to reliably “fix” it. You might find ways to outwit the new competitor, but if you succeed it will be more good luck than good management; rewards or punishments for your success or failure are likely to be inappropriate in any case. You will likely not even really know whether your ultimate success or failure had much of anything to do with your actions. The thing about complex situations is you can never know.

So if we can’t “fix” a predicament, what are some of the best ways to “appreciate, accommodate, adapt to and work around it”? And how can we get the oblivious command-and-control psychopaths most of us have worked for to appreciate the intractability of predicaments, stop asking us to “fix” them, and let us get on with doing our best at what we do?

My philosophy on this differs from that of most of the complexity theorists who get paid for helping their clients deal with complex predicaments. If they want to continue to get paid, they need to offer the client more than “it’s a complex predicament so there’s no solution”. They will suggest ways to intervene (in a way they’re offering a kind of corporate therapy for what is in fact an untreatable condition).

I’m not much for therapies that suggest that you can fix what you can’t. Call me a defeatist (you won’t be the first) but I think there’s a lot to be said for acknowledging what we don’t know, what we can’t predict, and what — no matter how gargantuan and powerful we might grow to be — we really can’t hope to change. Pollard’s Law of Complexity says (sorry for those tired of hearing it):

Things are the way they are for a reason. To change something, it helps to know that reason. If that reason is complex, success at truly changing it is unlikely, and adapting to it is probably a better strategy. Complex systems evolve to self-sustain and resist reform until they finally collapse. That is just how they work.

What we can do is to learn more about the complex predicament, and about our own situation (personal and community) trying to deal with that predicament. And we can try some things out, some of which (unpredictably) may seem to work, to some extent, at least for a while.

When I talked to clients about complex predicaments (I’m long retired), I tried to keep in mind that people dealing with such predicaments are a lot like squirrels facing a squirrel baffle blocking their access to a birdseed container. The squirrels have no control over the situation with the baffle, which may suddenly change in unpredictable ways. All they can do is explore it, experiment, and try to work around it. Humans dealing with complex predicaments are really no different.

Here are ten things that I often tried to do during my career helping small enterprises tackle big challenges — things that we can do to explore and learn more about complex predicaments that we can never fully know or understand, and to experiment with them, work around them, and adapt ourselves to them as the situation changes:

- Do primary research: As contrasted with searches on the internet (secondary research), primary, face-to-face conversational research gives us context for the knowledge, perspectives, and insights of those who’ve been dealing with this predicament already, about what they’ve learned, and what they’ve found to work, and not work, and why. It gives us a chance to go deeper than lazy online reading and data collection (based on conclusions that support the author’s view and reputation, validly or not) can ever hope to offer. Ideally those conversations should be recorded and/or transcribed so that each collaborator can draw their own conclusions and insights from them, and then the group should apply collective sensemaking to assess what all this research means.

- Get all the voices in the room: Many causes tend to attract like-minded people who are at the same point in their exploration of a predicament. The “wisdom of crowds” demands a diversity, at least of knowledge, backgrounds and perspectives, and ideally of experiences and competencies, of collaborators. And of course it requires actually listening to those diverse voices, attentively, thoughtfully, and without judgement, Bohm- or Schmactenberger-style.

- Surface the misinformation and myths: It’s amazing how often dogma — about why things are the way they are, or about what works and doesn’t, or about what’s been tried and hasn’t, about whose knowledge and insights are most valuable, and about what’s possible and what really isn’t, and why — prevails over what’s really true, often just because it’s repeated the most by those who a group or culture trusts the most. We all have blind spots; we all think we know more than we really do. When you start with presumptions that are incorrect, stories that are compelling but untrue, and facts and ideas that you want to believe but shouldn’t, that faulty foundation is bound to let you down.

- Capture stories not just data: Stories, provided they’re true and not dangerous myths, are powerful because they’re memorable, they suggest trajectory not just current state, they capture the imagination, and they’re more engaging than the most persuasive facts and charts. Military campaigners don’t just study the data on past conflicts; they study the stories of success and failure to appreciate why and how things turned out as they did.

- Be modest in your expectations: There is no “fix” for complex predicaments, whether they be marital breakups or global poverty. Such predicaments can be explored and can sometimes (usually unpredictably) be influenced, but they cannot be “solved”. For that reason, “safe-to-fail” and “fail-fast” experiments are more valuable than large-scale gambles. Workarounds are often more effective than trying to blast away an obstacle. Most of all, it’s important not to take the credit — or blame — when things turn out perfectly, or much better or worse than expected, since your intervention probably had little to do with it! (In any case, people who don’t care who gets credit for their good ideas, suggestions and work generally accomplish much more than those who do.)

- Iterate: Conversations are inherently iterative, back-and-forth exchanges leading towards understanding, clarity, and appreciation. In general, iterative work recognizes that the understanding of a complex predicament co-evolves with the understanding of possible approaches for dealing with it. Design purists tend to dislike iteration — it’s often inefficient and involves a lot of rethinking and starting over. But it’s how we learn, individually and especially collectively. In complex situations where knowledge is inevitably incomplete and evolving, it’s how we learn best.

- Avoid the safe way: Goethe said that boldness has genius and magic in it. Having the courage to try something radically different that has been carefully thought through does not mean foolhardiness; rather, it means having the collective will to take a path that is not the safest or least risky when both the potential success and the likely danger of failure are higher. I’ve seen tragic situations where at the last minute a group backed down from a potentially magnificent, radical initiative, in favour of a more timid, lower-risk, lower-potential one. In many cases, that timidness leads to failure.

- Beware of “magic” technologies: Mars colonies; hydrogen energy; geoengineering. Our fascination with fantasy and sci-fi grooms us to want to believe that technology can fix everything. Yet every technology ever invented has created challenges at least commensurate with its benefits. Whatever your predicament, a database or an app is unlikely to be the solution.

- Objectives are not strategies: When you read, in a so-called “strategic plan”, a “strategy” in the form: “Develop a plan to produce [end result]” it is simply not a strategy. A strategy describes specifically how you are going to achieve an objective, almost always including what you are not going to do (any more, or instead) to free up the time and resources to pursue this particular strategy. If your “strategic plan” is mostly just objectives, it makes sense to set most of them aside and develop an actual strategic plan to actually achieve a few of those objectives.

- Chunk it: Just as you can’t solve a (merely complicated) Sudoku puzzle by taking it all in at once and simultaneously filling in all the numbers, you can’t effectively address a complex predicament without breaking it down into manageable “chunks”. The key is all in how you chunk it. If you break the task down by roles and assign people to each, you’ll lose the benefit of collective wisdom, and, since you also have to iterate, probably have to do many things over and over again to consider and incorporate new discoveries, ideas and learning. Techniques like visual recording and systems diagrams (which may also change as knowledge and collective wisdom evolve) can help a group assess what are the logical “chunks” — things to work on together, and in what approximate order. Like most complex predicament work, it’s an art, not a science.

gif of chess master Patrick Wolff from a post on chunking when dealing with complex situations, by Richard Maltzman

There’s a propensity among the lazy and idealistic (speaking as someone who’s inclined to be both) to put unrealistic “placeholders” in place of practical actions, to make apparent great leaps forward in achieving one’s objectives in grappling with predicaments, when those placeholders are dependent on some factor that is actually beyond your group’s control. So it’s important that your plan avoid steps that depend on:

-

- changing people’s minds (ad industry hype notwithstanding, it rarely happens)

- achieving a “culture change” (which generally only occurs when a generation dies off and a new one takes power, and often doesn’t even occur then)

- finding needed resources (the ultimate excuse for not being able to proceed)

- some future event happening (it rarely does)

- “we all need to…” type statements (ie magical and/or wishful thinking)

If you’re reading an analysis or proposal or plan that includes such dependencies, please stop wasting your time. If you’re writing plans that include such dependencies, it’s time to stop kidding yourself and your client or audience and get real. Recognizing the current situation and its constraints isn’t defeatist — it’s honest and pragmatic and can liberate you to start focusing on things that you can actually control and accomplish.

Squirrels trying to beat the baffle know these things. They know to watch other squirrels try, and learn from them; that collaboration works better than solo effort (I once watched two raccoons, one on the shoulders of the other, unbolt and completely dismantle a bird feeder with a squirrel baffle in under five minutes, including carrying off the metal baffle); that it’s important to overcome misunderstandings and preconceptions about the system they’re studying; that the reasons for success and failure are usually complex and not straightforward; that small successes are better than huge failures; that approaches need constant tweaking to improve their likelihood of success; that sometimes they need to be bold and take a chance on something scary and risky; that the tools at their disposal are usually limited in how much they can help them; that really wanting something badly is rarely enough; that good strategy means giving up doing something that wasn’t working; that it’s often best to break a tough challenge into more manageable smaller ones; and that sometimes it makes sense to give up and move on to another, less intractable, objective.

So you might do yourself and your collaborators a favour by thinking like a squirrel next time you or your group are dealing with a complex predicament like:

-

- the healthcare system in your country, or how it’s handling CoVid-19

- dealing with a family or organizational break-up

- how to best look after elderly or dysfunctional family members

- coping with poverty, addiction, inequality, racism, a fragile economy, and runaway climate change

- most socioeconomic and ecological “system problems”

- issues with the human body and other organisms

As for how to deal with self-obsessed, arrogant bosses who are clueless about how to actually, effectively deal with these kinds of situations, I have no real suggestions, other than to find better work. Now that‘s a complex predicament.

Dave, that sums up the US Congress’s approach to problem solving quite accurately.

I like to use a paint-ball metaphor for US law. Congress shoots a metaphorical monetary paintball at a problem without making an effort to aim accurately. If the money even hits the target, it barely plugs the crack in the failing system. But, a lot of the shot misses the target and splashes on nearby taxpayers who need no help but are happy for the freebie. Their glee drowns out the moans of those in need. Congress seeks blame; not information, if things get way worse.

“So you might do yourself and your collaborators a favour by thinking like a squirrel next time you or your group are dealing with a complex predicament like:…”

About thinking and Doing:

I started ‘reading’ (some) Western :) philosophy at about age 20 – (Plato, Bertrand Russell et al.) partly through being an inquisitive ‘soul’ (Jung and Hillman) and a creative artistic person, (A. Ehrenzweig and H. Read) Since then i consider myself a creative general learner.

As an undergraduate, i read (some) German philosophy, (Kant, Nietzsche and Schopenhauer) and some East Asian, including people like the monk, Thomas Merton…

Around 2005 i got know you a little, probably through you, i got to know about Dave Snowden’s work. Within all this, i was/am/will always be an artist. (I won’t bother you with detailed art references here, too many)

Over the years since 1997 i have gotten a little into the published thoughts of ‘you’ and Dave S…and many others whom we all know (about).

Nowhere in any of this’stuff’ outside of great imaginations like, say, Walt Whitman [grounded in Nature and yet Transcendental] – can i recall or even imagine that the life (thinking/doing/knowing) of a squirrel is a useful touchpoint for the human predicament.

Dave S has built up, ammassed a huge description (narrative, signs and symbols) including cartoons, mainly aimed at the clueless and nearly clueless market, (and, i am sure there are some very impressive words for it that you can call upon,) in order for them to better negotiate the almost infinite gradations called ‘life’ (i.e.,- increasingly complexity) along with the necessary complementary, ‘destruction and death’…(evolution on the grand scale) in the round.

What little i think i know :) on this topic comes from, then, 50 years as a creative person. My [original] ‘creative work’ was first published in 1974 by Oxford University Press. I make no grand claims, i just put it there. 40 years later, learning about my ‘creative work’ and ‘experiencing it’ firsthand, with ‘reports’ from various sources :) as to its potential toward helping (with) complexity, both as phenomenon and ‘topic’. We spent two days together in California. We talked about (some of the above) including, emergence, art, creativity, technology and general matters of human concern. No, we did not get as far as squirrels!

In 2002 i took a chance, after five years trying to understand the topic (complexity) via my mate At de Lange of Pretoria and i sent ILya Prigogine some modest work i’d done, around and about Alan Turin, butterflies, otherness and love – Oh! And some old master drawings (‘think’ Leonards and Michelangelo.) Unlike many people today (think COVID) applying for menial (any) jobs to save losing (for example) their houses, i did get a reply. From that i got the impression (‘think’ Monet and van Gogh) that my in-tutions (think Oxbridge) were along the correct, general lines. I was astonished. He is called in some quarters the Poet of Thermodynamics. He also wanted to become an artist when young! But that’s even more perislous than what you and Dave S have been doing all ‘your’ adult lives :) So he went into chemistry.

From the point of view of our human, all too human predicament(s), i humbly offer that the squirrel should be removed from your peice. It is not good practice for humans to ‘think like’ a squirrel.

In ART (painting) ‘colour theory’ there are just three primary colours, and then three secondaries with thence almost innumerable tertiaries – white can lighten a colour in tone, but this will remove some of the chromatic intensity. Intensity can be regained to a limited degree by what other colour one places next or near to that colour. If you mix up :) those two colours though, the outcome is a dull grey tone.

When an artist, who has spent much time, (years) and free-energy in studio/outdoor practice (getting experience with light, form and colours) the last thing they do is think, or ‘go compare’ :) consult a chart or the ‘colour wheel’. It is too complicated to enter into the complexity of that here :) Perhaps you can imagine how van Gogh came by his ’emergences at the edge of chaos’ :)

Picasso it is reported, one said at a cafe table…Look at the green of THAT olive. I could mix a thousand tones/hues of that olive and never capture THAT green.

I’ll leave it at that, for NOW,if i may.

Edit/add

The ‘we’ not named in para 5 is /me / and /W. Brian Arthur/.