A rat who is working for food suddenly hears a warning signal followed by a shock he can do nothing to avoid. After it stops, he goes back to working for food. But soon, even the sound of the signal is enough to stop him from seeking reward. Even though he could continue painlessly during this interval to obtain food, he seems crushed by the anticipation and now “crouches tensely, trembling, defecating, urinating, hair standing on end.” The animal is, in scientific terms, scared shitless. He can do nothing to control his fate, and that is untenable.

— Melissa Holbrook Pierson, from The Secret History of Kindness

Neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp spent his life attempting to map human emotions, explain them in terms of brain and body chemistry, and advocate for all animals on the basis their emotions are indistinguishable from ours.

The model he ended up with included seven categories of emotions (what he called ‘affective’ states) and corresponding, commensurate instinctive emotional behaviours for each. I’ve integrated them with Karla McLaren’s model, and separated out those that seem to be mostly enduring feelings we can carry or a long time (left column), from those that seem mostly situational and fleeting (right column):

| Enduring Emotional States | Situational Emotional Feelings |

| angry, hateful, envious | enraged |

| anxious, jealous, unappreciated | fearful, apprehensive, bored, attention-craving, feeling ignored, helpless, abandoned, or trapped |

| sad, sorrowful, ashamed, grieving, guilty, apathetic, depressed or hopeless | grieving, panicked |

| pleasure-craving, longing, lonely | pleasure-craving, lustful |

| equanimous, enthusiastic | joyful, playful, curious, seeking-to-explore or discover |

| affectionate, loving | caring, protective, reassuring, compassionate |

You’ll notice that two of these emotions, grieving and pleasure-seeking, appear in both columns because I think we can experience them either as enduring phenomena or acutely in the moment.

I would argue that wild creatures experience only the emotions in italics, which include (1) all the ‘situational’ emotions in the right column, plus (2) the ‘natural state’ emotions that are present in wild creatures most of the time (alternately equanimous and enthusiastic), plus (3) their emotions when they are suffering from chronic stress (anxious, like the cat with separation anxiety or the low-status baboon, or apathetic, like the chained junkyard dog). Sadly, as we encroach more and more on wild creatures’ habitats and freedoms (particularly in the case of factory farms and inadvertently mistreated pets), I think we’re seeing more of the latter.

I think that wild creatures likely feel all these emotions more intensely than we do (as there is nothing veiling them from feeling them full-on). But most of these situational emotions (the ones in the right column) are fleeting, lasting just long enough to deal in an evolutionarily successful way with the particular situation. And then it’s back to the alternating states of equanimity and enthusiasm we witness so often in our pets and wild animals.

And the reason I think they don’t feel the unitalicized feelings is that these feelings require a story, a rationalization, a judgement about intent, cause or motivation, which I believe requires a sense of self-hood and separation that these creatures (blessedly) lack. If you think you’ve seen evidence of a pet or other wild creature you’ve observed feeling that emotion, my guess is that what you’re really seeing is one of the italicized emotions in the same row of the chart. So we might mistake a cat’s attention-seeking for loneliness, or its acts of apprehension for love.

If the thought that your pet perhaps doesn’t really love you strikes you as outrageous or absurd, here’s what Melissa says on that score:

This is the basis of my dogs’ storied love for me, their one and only. Only I know the real truth. It is not this Melissa they love. If they bark menacingly at someone who approaches, they are not doing it to ensure my safety. There is but one thought in their minds: do not harm this person, for she is my most valuable possession. My large Swiss army knife, the one with all the extra attachments.

When I speak with people who have lost their sense of self and separation, they tell me that, when the illusory sense of self and separation is lost, the italicized emotions continue to arise, but they don’t arise ‘for’ and are not claimed ‘by’ any ‘one’, so they don’t seem to last long. But nothing in their behaviour appears to have changed — these instinctive, conditioned feelings are just part of their instinctive, conditioned nature, and they have no need for a ‘self’ in order for them to happen.

And while the unitalicized ‘self-created’ emotions may also still arise in them, they seem to do so less and less often, because the story that validates them is just seen to be a fiction. Without a self and a story to justify these feelings, they just arise and quickly dissipate. And these self-less characters are absolutely fine, and apparently little changed in their demeanour and behaviour, without them!

It is especially perplexing for some when they assert, for example, that their affectionate fathering and marital behaviour is unchanged despite it now being obvious that there is no one, no father, no children, no spouses, and no relationships — with the objects of their affection agreeing that nothing has seemingly changed!

I have attempted to argue (as Melissa asserts) that it is our biological and cultural conditioning, in the context of the situation in the moment, that entirely dictates our behaviour. My sense is that we are conditioned to feel the italicized emotions by our biology and our culture, but the unitalicized emotions are entirely self-constructed and self-inflicted, and have no basis in reality. We make up a story about what we think happened, or wish happened, or want to happen, and then we react to that story with these feelings, some of which prevail over our whole lives. Without a story, these feelings can never make sense. And all stories about the past or the future are fictions.

Jaak attempted to map the chemistry of emotions, with the objective of developing drugs that could treat unhealthy excesses of emotion without numbing the patient. He didn’t succeed (his only developed drug failed phase III trials), but I’m wondering if that’s because his successful experiments were all with wild animals, while the human emotions he sought to moderate with his drugs were mainly the unitalicized ones that his lab animals likely didn’t feel. Perhaps his failure was just considering the italicized and unitalicized emotions as equivalent in each category, when it turned out that what tempered a wild animal’s grief could not temper a human’s depression, and what tempered a wild creature’s rage could not control a human’s anger. The drugs can modulate the chemical flows in our bodies, but they can’t change our stories.

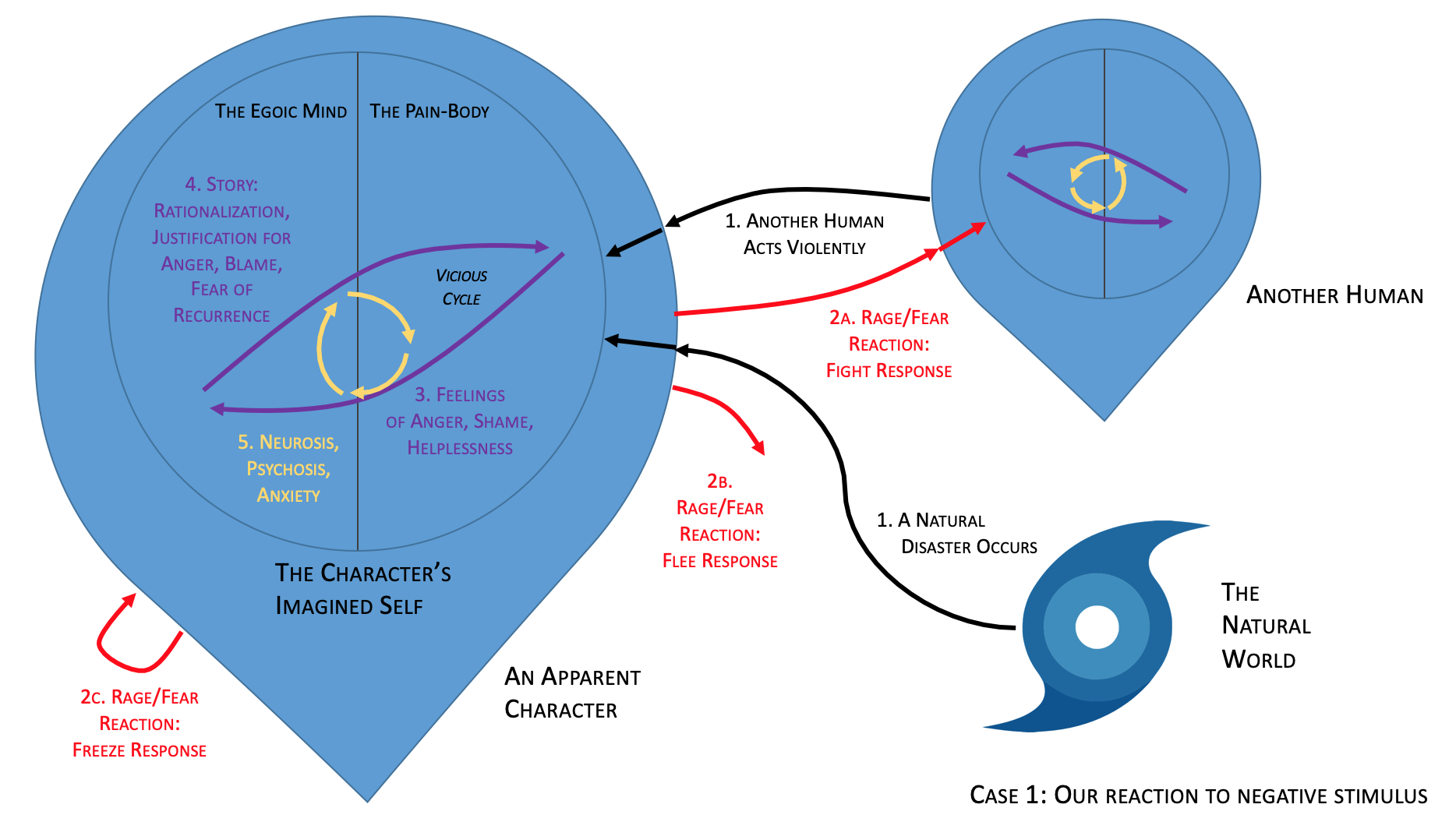

Eckhart Tolle writes about how our embodied emotions (“pain-body”) and our rationalizing brains (“egoic mind”) can create a vicious cycle: We feel angry; then the brain rationalizes that feeling (“X did something hurtful”), and amplifies it through judgement (“It was deliberate, cruel, and premeditated, and X needs to be punished”); that creates more feelings of anger and perhaps hatred, which provokes more righteous indignation and rationalization for those feelings, resentment, ideas of revenge and retaliation, and so on, ad infinitum. The consequences of this unending, sometimes escalating cycle can be wars, at various scales from personal grudges and vendettas to civil and international battles, that can go on for generations.

These vicious cycles only apply to our self-produced, story-dependent (ie the unitalicized) emotions, and are hence, I would argue, unique to humans.

When a human accidentally hurts a cat during play, the cat will instinctively reply with an act of fear, rage, and/or panic, but it will not assume the hurt was deliberate (why would it?), and it will not plot revenge for it. It will not feel angry, sad, hateful, ashamed, or guilty. It will lash out or flee and hide, but soon all is forgotten, other than perhaps the memory that may evoke an act of caution if similar situations arise in future, until it appears that there is no recurrence of the hurt, and then unbridled play resumes.

This is pure conditioning. The cat is not an automaton, and certainly feels pain. But its conditioned responses to each situation, benefitting from millions of years of evolution, are instinctive and protective, and not judgemental, scheming or spiteful, because such an entanglement and escalation of feelings and rationalizations is not in its interests and probably not in its capacity.

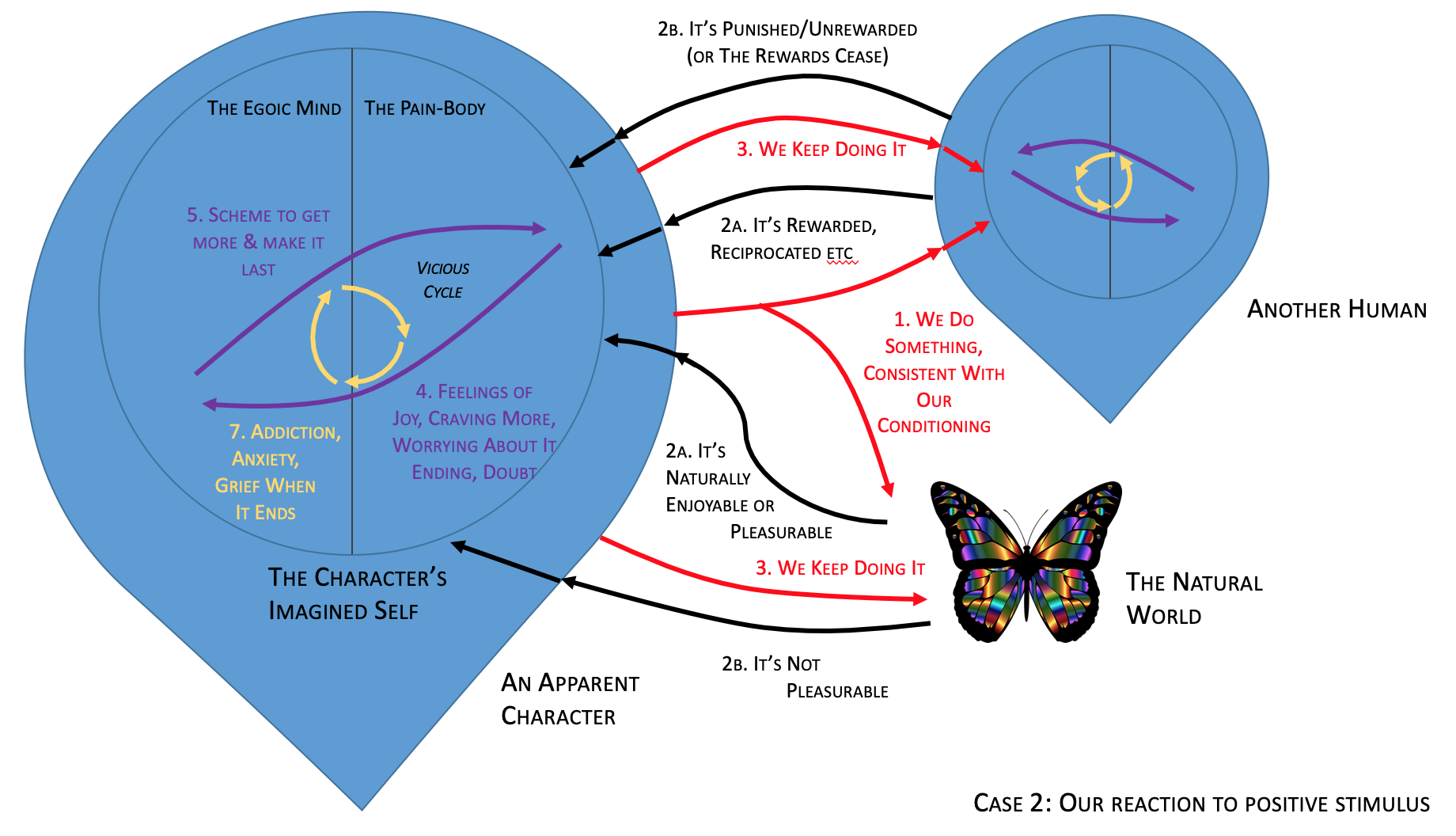

In the quote at the start of this post, Melissa Holbrook Pierson argues that all our behaviours are governed by our conditioning, and that the most effective means of conditioning any creature to behave in a certain way entails giving it the power to consistently achieve a pleasurable result (a treat for the dog, a trophy for the human, or even just the rush of pleasurable chemicals in the body that simple praise evokes) for a certain behaviour, rather than punishing it (yelling at the dog, jailing the human) for an undesired behaviour. This is how we are wired.

The rat in Melissa’s example is clearly paralyzed by deliberately human-induced anxiety. But it is not creating a story about causality between the warning signal and the shock. Its instincts for fear and apprehension have been deliberately triggered by the experiment, and, unable to fight or flee, it freezes, the only response left to it. It is, at least briefly, conditioned to fear the warning signal (much as we are with emergency alert alarms). But without a story, or recurrence of the conditioning shock, the rat won’t go on responding fearfully to the warning signal much longer, just as, if we hear too many emergency alert alarms that turn out to be false, we’ll stop reacting to them. Though, because we may be making up ‘worst case’ stories about them, it may take us longer than the rat!

Here’s how this conditioning and emotional response might play out in two different situations:

In Case 1, the human’s self turns a simple fight/flight/freeze instinctive response into a vicious cycle of emotions and stories justifying those emotions, potentially leading to an escalating fight, an unhealthy and unwise response, and long-term mental illness and trauma. Erase everything in the “Character’s Imagined Self” circle and you see how intuitively and intelligently wild creatures would deal with a similar situation — respond, shake it off and forget about it. What’s especially cruel is that for all the mental anguish, the self isn’t actually doing anything — it’s just making up stories to justify its response (which wasn’t ‘its’ at all), and then getting roiled up in self-produced emotions that those stories trigger.

In Case 2, the human’s self snatches defeat from the arms of victory, trying to hang on to something simple and good, stressing about making it last or losing it, instead of just enjoying it. Again, erase everything in the Character’s Imagined Self circle and see how effortlessly wild creatures are able to just be, and why they’re so much more equanimous than we are.

As Melissa puts it:

The same law of behavior affects all creatures’ actions: we do something, it produces pleasure or it produces pain or it produces nothing, and the result determines whether we continue doing it, stop doing it, or do it differently, and these are the only options. The bedrock rules of behavior function to our preconceptions much like the swallowing of that yellow and red capsule.

And so perhaps we’d be wise (if we only had the free will to do so!) to learn from our furred and feathered friends about the utter non-necessity of all the thoughts and feelings and stories we impose on every single situation, trying to make sense of it while just making it needlessly complicated and stressful.

A final thought: I listed above, based on my observations of pets and wild birds and animals over the years, two enduring emotions that I think are the ‘natural state’ for all wild creatures, when they’re free of human obstruction: equanimity and enthusiasm. I have seen cats and dogs and birds and squirrels and wolves and deer exhibit this effortless, gentle back-and-forth movement between the passive and the active tense.

And I have also seen precisely the same states, and the same movement, in a very few, fortunate humans — who have also been the most perceptive, the most creative, and the most inspiring people I have met. That capacity to move from being equanimous, open, attentive and non-judgemental, to being curious, exploratory, and passionate to discover and learn new things, is perhaps as close as we humans can hope to get to the perfect state that is every wild creature’s birthright, and which we have forgotten.

So now I’m going to put some birdseed out, since there’s some snow on the ground, and spend some time watching the masters.

Thanks for thinking this stuff out, Dave…much to reflect on like your last post and many before.

Many humans like to think of themselves as bouncing between equanimity and enthusiasm…like to think I’m there for an hour or two every so often. Now that you have framed the emotions of animals and humans I feel a shambles. I’ve got some great quotes and “spiritual learning/practices” but this life is demanding even in the best of situations. The gentle back and forth between a passive and active tense is so quickly and easily polluted. Will try again tomorrow to keep my separate / in-existent self from stealing the moment away.

There’s a feeling here that this is looking like another story about something perceived as “perfect” when you have to make some assumptions about how an animal is.

This is not to say it’s not appealing. Even the story of people losing a sense of self having more of the qualities that are seen as preferable. How can it be known that the loss of sense of self isn’t just another story?

I suppose that’s ended up stating that there isn’t any knowing?

Glad for the convoluted and contradictory thoughts – reminds me of koan.

Philip: Thanks. Yep, for sure. This “trying to not let the self get in the way” — presumably that has to be a conditioned behaviour as well, as well as a hopeless one.

Nathan: Agreed. There are only stories, at least for the “me” constrained to use language. We are condemned to try to make sense of what we sense does not make sense. It’s the only thing we can do.