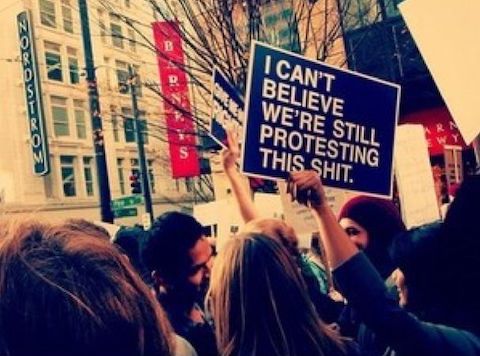

photo from a women’s march, source not cited

In a recent article in the New Yorker, Jelani Cobb chronicles the work of Derrick Bell, considered by many the father of Critical Race Theory (CRT). It’s a strange name for a fairly straight-forward, compelling and much-misrepresented thesis: Racism is so deeply rooted in the makeup of American society that it has been able to reassert itself after each successive wave of reform aimed at eliminating it.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because the same thesis could be applied to many of the other abominations that progressives keep thinking have been done away with, only to find that they’ve never gone away at all, merely stayed underground for a while until the political climate, at least in some circles, is willing to tolerate them again. Things like: misogyny (revitalized by Trump and incel-baiting academics like Jordan Peterson), forced-birth laws, climate change denial, xenophobia, anti-science, anti-authority and anti-regulation paranoia, and homophobia, just to name a few.

So now the message of CRT is being deliberately and systematically distorted, including by the right-wing ‘media’, to portray it as a kind of blame-y reverse racism and perverse thought-censoring ‘wokeness’, all rolled into one. Right-wing hate-mongers like the governor of Texas (and eight other copy-cat states) have encouraged this reactionary behaviour by banning the teaching of anything related to race in the states’ schools. Such behaviour, of course, perfectly (and ironically) confirms the validity of Derrick’s thesis.

I have argued that our very nature and conditioning impede our capacity to bring about and sustain positive social change. My sense from studying history and culture suggests that social, political and economic change happens only when the old generation dies and a new generation with different entrained beliefs and imperatives fills the power vacuum.

So, I would say, change can happen when the new generation has different entrained beliefs and imperatives. For example: We no longer (with some notable exceptions) tolerate overt slavery on the basis of race. Women (in most countries) are allowed to vote and hold office (and usually do so more competently than men). Torture cannot (legally, in most places) be used as a form of punishment or to extract confessions for alleged crimes. Even in our current age of growing fascism, I think reversion of these changes is unlikely to occur.

These changes have come about to rectify what I believe are appreciated instinctively and globally as ‘inhumane’ behaviours, and those behaviours are, I think (at least over the million-year horizon of our species’ existence), relatively rare and aberrant.

In contrast, abominations like racism, misogyny, xenophobia, and epistemophobia (a word I just discovered, meaning fear and distrust of science and knowledge), which seem generally to have their roots in people’s aversion to things that are unfamiliar and hence considered threatening, are more challenging to stamp out. The irrational fear and hatred that underlies them is so widespread and so long-standing that it is often not even consciously recognized. And so this fear and hatred engenders broad, sustained, institutionalized, unchallenged, individual and collective physical, social, political, economic and psychological violence. In other words, the problems that this fear and hatred manifest become systemic.

It therefore doesn’t surprise me that the battles against these ills need to be fought again and again, especially as the stress level in our society ratchets up ever-higher.

The staying power of these systemic ills occurs because the underlying beliefs are often passed down, within each demographic, largely unchanged, from generation to generation. Increasingly and depressingly, for example, young white males tend to vote, on many issues, the same way their old white male parents do.

This heritability can be particularly insidious when it’s unconscious. Many racists and misogynists I have met are entirely unaware of their fear and hatred, because as long as they don’t openly act on it, they can plausibly deny, at least to themselves and to their children, that they are racists or misogynists.

Paradoxically, young people might be more prone to pick up and sustain their parents’ racism or misogyny when it’s not acted out — the fear and hatred is subconsciously inherited by a combination of insinuation, unchallenged beliefs that imply fear or hatred might be understandable without saying so categorically, along with observed aversive behaviours, misinformation, and simple exclusion from, or prohibition from, contact that might dispel the fear or hatred of the unknown group (eg in segregated communities, clubs, schools and institutions).

Whereas if Mom and Dad wear MAGA hats while aiming armed weapons at peaceful protesters of colour passing by their house, the kids may recognize the folly of their parents’ fearful or hateful beliefs and behaviours, and adopt a radically different set of beliefs and attitudes.

The media, by sensationalistic reporting of unrepresentative groups and extremist individuals, and by encouraging misinformation (the more outrageous, the stronger the response and the more attention for advertisers to exploit), amplify this fear and anger, and hence abet the retrenchment of fear-driven attitudes and hatreds, and deepen the resultant social ills.

And this enables reactionary populist fear-mongers like Trump (and Hitler) to use these media to ratchet up the hatred, fear and distrust that they depend on to galvanize their base, making sustained liberalization of attitudes and beliefs almost impossible.

Though we pride ourselves on our rationality as a species, what we believe has more to do with what and how we feel than what we think. Even science is not a purely rational, objective undertaking, as Stephen J Gould stressed in his book The Mismeasure of Man:

Science, since people must do it, is a socially embedded activity. It progresses by hunch, vision, and intuition. Much of its change through time does not record a closer approach to absolute truth, but the alteration of cultural contexts that influence it so strongly. Facts are not pure and unsullied bits of information; culture also influences what we see and how we see it. Theories, moreover, are not inexorable inductions from facts. The most creative theories are often imaginative visions imposed upon facts; the source of imagination is also strongly cultural.

No surprise, then, that in this age of supposed science and reason, our emotion-charged credulousness has amplified anti-intellectualism, distrust of science, scientists, scientific facts, and scientific institutions, and, among other things, extended a pandemic that should have been over a year ago, and unnecessarily quadrupled its death toll.

The upshot of all this is, of course, not what progressives want to hear. History is not a story of steady progress punctuated by brief periods of backsliding. It is, instead, an endless and un-winnable battle against fear, hatred, misinformation, and the psychopaths and the clueless who exploit it all in times of stress to foment systemic violence, ignorance, and folly. And then we lick our wounds and prepare for the next round.

Conditioned as we are, we can only do our best to deal with it all, to make the best of it. History, for us, it seems, will not be a story with a happy ending. But we have no choice but to keep fighting to make it, at least, a tiny bit better than it might have been had we not tried.

If progress against “fear, hatred, misinformation” was incremental (and possible), one would think that after many thousands of generations since we became homo sapiens we would find ourselves in a world where fear, hatred, and misinformation hardly existed at all, and then perhaps only because of brain injury.

So, I think M. L. King Jr. was wrong when he said, “The arc of history is long, but it bends toward justice”. It’s an uplifting thought, but I think the evidence of history since hunter-gather times is that it doesn’t bend at all, but fluctuates about a constant (too low) level of justice and good will.

There are probably sound evolutionary reasons why we still succumb to fear and hatred (along with an incredible incapacity for long-term planning), but those reasons are very complex and context driven, resulting in evolutionary psychology being a complex and contentious field of study (a field in which I am no expert at all).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolutionary_psychology

I will, however, follow your advice and keep on fighting.

Thanks, Joe. I don’t think anyone is an expert in evolutionary psychology, but then I’m a Gouldian. As for keeping on fighting, it’s not as if we have any choice.