The cognitive bias codex from wikipedia; if you want to print it out so it’s legible and useful, print the original over four letter-sized pages and paste them together (my printout is taped, tellingly perhaps, over my rarely-used TV). The model was developed by John Manoogian III and refined by Buster Benson; the online version includes links by TillmanR to the wikipedia articles explaining each bias.

Humans learn in a variety of ways: We learn by watching others, and seeing what happens. We learn from demonstration, and explanation. We learn from practice — trial and error, learning from our mistakes.

But one of the ‘stickiest’ ways we learn — by which I mean one of the ways our learning stays with us over time, even in the face of evidence that undermines what we think we’ve learned — is by listening to stories.

We are highly vulnerable to the messages of stories because their point of view, and their bias, is rarely right in our face. When we listen to a story and ‘relate’ to it, we imagine we are free to draw our own conclusions. To this extent, stories are subversive.

But worse than that, stories can be and often are manipulative. A story is often a sales pitch — hence our attraction to testimonials and ‘independent’ ratings of products and services. We are already predisposed to buy, and are looking for confirmation. If we read a bad review, that disposition can quickly slew 180º, as we look for confirmation of that story instead.

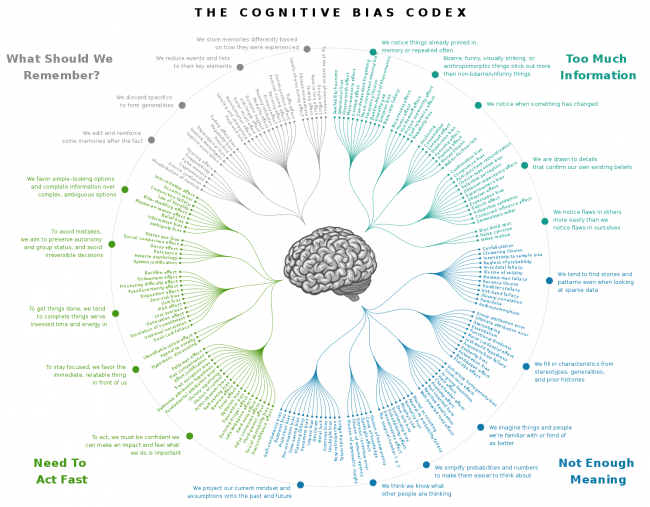

This manipulation employs, sometimes not even consciously, a whole bag of tricks that exploit our vulnerability to many cognitive biases. These biases are baked into our human DNA and our artifacts and processes, including our languages. Many of these biases seem to enhance the survival of our species, by simplifying learning and decision-making, making us more comfortable with what we’re facing, and drawing us together (since we can’t survive alone). Our brains are interested in what can help us do this, and the ‘truth’ — what’s ‘real’ and what’s really happening — seems to be of secondary importance.

And these biases show up, in spades, in our stories. Read through the explanations of these biases and it’s easy to find obvious examples where stories have exploited each of them.

At a retreat a few years ago, put on by Dark Mountain founders Dougald Hine and Paul Kingsnorth (yes, the irony), one of the things we worked on was a harvest of modern myths, some of them directly contradicting others. Note that myths aren’t necessarily wrong — a myth is any story believed collectively by a significant number or group of people. It’s not hard to understand why people hold to these myths, for the three reasons cited above (ease of action, comfort/reassurance, and social cohesion). We want to believe the stories of our peeps.

I largely gave up watching TV and going to films (and reading a lot of fiction and non-fictional “analysis” that was poorly supported) a few years ago. I just couldn’t get past the whoppers we were being asked to swallow.

The most popular movies always seem to be about (fictional or historic) heroic individuals who overcome ridiculous obstacles and horrific, ruthless enemies and prevail as models for us all. Or they’re about horror movie baddies who cannot be killed. Or they’re dramas and “suspense” movies about suffering — to make us feel better about our own lot by comparison? Or they’re comedies that belittle others, so that presumably we feel better about ourselves. Or they’re documentaries with magical, simplistic “we all just need to…” prescriptions at the end. Awful, manipulative stories, all of them.

And they all seem to have one-dimensional (slightly flawed hero/wronged villain) characters and a standard myth plot about inevitable struggle and inevitable progress. Why do we keep falling for these fictions? Why don’t we like movies and novels that present the world as it really is, in all its complexity and uncertainty and directionlessness, and which help us learn about the world and history and human nature, and imagine possibilities?

Why are we drawn to stories that serve us badly?

I don’t know the answer to this question, but I have some thoughts about

“wrong answers” to it. I don’t think it’s because humans are stupid. And while I think we have been (for understandable reasons) dumbed down and deprived of the opportunity to practice critical thinking and other skills and capacities, and to acquire relevant knowledge of history and science, I don’t think it’s this lack of skill, knowledge and practice that underlies our attraction to stories that serve us badly.

And although we’ve been brainwashed, propagandized and manipulated into believing falsehoods and half-truths because that serves the vested interests of the rich and powerful, I don’t even think it’s because of this that we’re attracted to, and buy, stories that serve us badly.

Most of my life I was attracted to such stories. My blog is full of utter nonsense that I once believed passionately, especially in the early years when the blog was almost embarrassingly popular. Why was I attracted to such stories as: 9/11 being “conceivably” an inside job, or the “dangerous” use of squalene in vaccines for the military simply because it was cheaper to use GIs as guinea pigs? Or business “management theories” based on “case studies” that were just fanciful inventions that had no more rigour or credibility than a slick PR piece?

Why did I want to believe these things were actually or probably true? Because they were novel and had a “ring” of truth? Because they flew in the face of “conventional wisdom” that I suspected was wrong, or boring? Because I fancied myself as counter-culture, or as an ersatz investigative journalist exposing the important truth of the lies of the rich and powerful?

I have no idea. It’s very possible that some of the things I believe fervently and write about now are dead wrong, or half-truths, and that by writing about them and believing them, I’m misleading myself and doing a disservice to my readers (the few who remain despite my changing my mind so dramatically on so many subjects).

Maybe our propensity to love and believe stories regardless of their truth or value, is just an evolved trait of the human animal that seems to have survived, even though it’s now a maladaptation that serves us badly, like our appendices or our fondness for sugars and salt.

All I know is that we humans seem drawn to, and even addicted to, our stories, and the beliefs they instil and reinforce in us, even when those stories and beliefs lead us astray. Much of our modern “civilized” world would probably not exist if we didn’t buy into all the stories that enable it to continue, that keep us doing what we do, even when it makes no sense.

Without our stories, where would we be?

These stories are needed, no matter all the bullshit and nonsense they contain.

Who cares about content, as long as they serve some basic purpose. The main purpose should still be to enhance group cohesion. If you believe some bullshit and all the other members in your in-group believe the same shit then you can rest assured. Everything is fine. And now you can go out with the members of your in-group and pick a serious fight with the non-believers in the out-group. They better join your group and believe all the bullshit you and your pals believe … or else …

“This is why he’s always been a figure of such importance to you. Even though the story itself made no real sense to you, you could identify with Adam as its protagonist. From the beginning, you recognized him as one of your own.” – Ishmael, Daniel Quinn