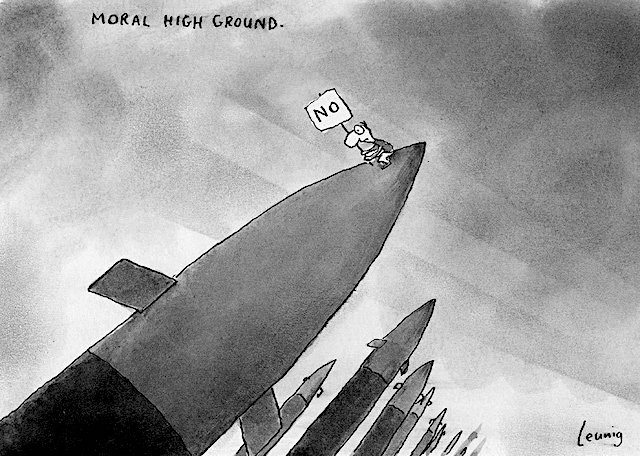

another astonishing cartoon by Michael Leunig

A dear friend said to me, a couple of months back: “You say that as if you know that for a fact; it’s just what you believe, which is ultimately just your opinion”.

At the time I responded with arguments to the effect that I didn’t consider that I knew something unless it had been corroborated by unimpeachable sources, and that I only believed things when I was satisfied “on the basis of a preponderance of evidence” that they were true. And, I added, I had a pretty good track record of changing my mind when compelling evidence to the contrary was presented.

But the more I think about it, the more I am convinced that she was right: Nobody really knows anything, and everything we claim to believe really is nothing more than our personal opinion, which is shaped by our conditioning, over which we have no control.

What an astonishingly different, more peaceful, less acrimonious, more open-minded world it would be if everyone would acknowledge this! But of course we won’t: Our beliefs and “knowledge” (even “expertise”) is too essential to how we self-identify, to our personal and professional reputations, and to our self-esteem. Accepting such doubts about the veracity of everything would lead to total paralysis, we fear, an incapacity to do anything decisive. It would be weak, easily-exploited by the “other side”, and therefore dangerous.

Though perhaps the world would be a better place if we were so “incapacitated”. It would be harder to organize a war, plot to hurt someone, foment an argument, or seethe with righteous indignation if we weren’t so damned sure of ourselves. The precautionary principle might actually prevail in some of our activities.

Our rush to certainty and judgement might be less of a problem if we weren’t so easily conditioned. That conditioning, oiled by money, by media misinformation, and by our desperation to want to know what’s right and true so that we can appear smart and be appreciated by others and protect ourselves and those we care about, can lead us to believe just about anything.

We can be conditioned to believe that genocides and lynchings and torture prisons are justifiable, and that lying to protect our beliefs, killing those who believe in different gods, and other acts of brutality, oppression and abuse, are morally justified.

And once we believe something strongly enough, no matter whether it is true or not, we are capable of terrible acts of violence, hatred and cruelty, acting on those beliefs.

So it is not terribly difficult to condition someone to believe that a traumatized, racist, hate-mongering misogynistic psychopath who would change his mind on any subject if it would make him popular, while lying incessantly about everything, and openly fomenting violent insurrection, is actually a country’s saviour, and their god’s choice to lead them out of a perilous moral morass.

And it is not terribly difficult to condition someone to believe that a senile, incoherent, war-mongering xenophobe who would change his mind on any subject to kowtow to his corporate funders, and who pays lip service to diversity and fairness and the climate crisis and the importance of public services while quietly enabling war-induced bankruptcy, nuclear brinksmanship, climate-destroying industries, and ever-greater inequality, is actually the only hope for a country, and that anyone who disagrees with him needs to be silenced at all costs.

And you can condition people in any country in the world to believe that their country is the most freedom-loving, the most democratic, and offers the most opportunity to citizens to become anything they want to become if they work hard and do what they’re told, despite the billions or trillions the country is spending to suppress information, to silence and suppress dissent, to fund wars, violence and militarized police forces, and to do the exact opposite of the clearly-expressed collective will of the majority of citizens.

You can condition people to believe that the current problems with democratic political systems are transient, and that they can be reformed in such a way that the top castes will respect and act upon the interests and preferences of the majority of citizens (rather than treating them as mere consumers of their party’s propaganda).

You can condition people to believe that the vast majority of citizens are sufficiently ideologically zealous that they would be willing to fight a civil war against other citizens in defence of their beliefs, and that only massive surveillance, censorship, restricting citizen rights, and appropriate political partisanship (and funding) will prevent this from happening.

You can condition people to believe, despite the overwhelming evidence of their public accounts, that the US and UK governments are not insolvent to the point of at least technical bankruptcy, and that their economies will somehow be able to repay or refinance all their debts in the absence of perpetual double-digit revenue and profit growth.

You can condition people to believe that shares in the Ponzi schemes called the “stock markets” are worth the paper they’re written on, and that real estate that is unaffordable to 95% of local citizens is not wildly overvalued.

You can condition people in any ‘developed’ nation with a rapidly aging population that somehow by magic their administratively-bloated, archaic, mismanaged health care systems, whether public or private, will not inevitably and completely run out of money and have to shut down entirely within the next decade or two.

You can condition people to believe that the quality of public education in almost every nation is not in precipitous decline due to chronic underfunding and administrative bloat, and that it can survive in any form for more than another thirty years.

At least, that is what I believe now, for the moment. That is just my opinion. I could be wrong. I don’t know for sure.

Love it, I think.

I recently read The Virtues of Ignorance: Complexity, Sustainability, and the Limits of Knowledge by Bill Vitek and Wes Jackson, a collection of essays that argues, as in this post, that we should have more humility in our “knowledge” and we should more often be willing to admit our “ignorance” (uncertainty). Lack of humility is rampant in our culture, so it’s not surprising that so many things we read about seem wrong headed.

(Sometimes we call people “stupid” when we really mean ignorant–while ignorance is very common and to be expected in our complex society, so it shouldn’t be a term of derision. Witness the gaping holes in my own knowledge. But it is awfully fun to believe that one knows, isn’t it?)

Yes for sure. Although I’m not sure that our arrogance about our knowledge and beliefs stems from lack of humility or the enjoyment of feigning knowledge, as much as a terrible fear of not knowing. I think we believe that not knowing is dangerous, and a sign of failure, weakness and lack of caring.

This article actually started out as a satire. I’m not quite sure how it ended up.