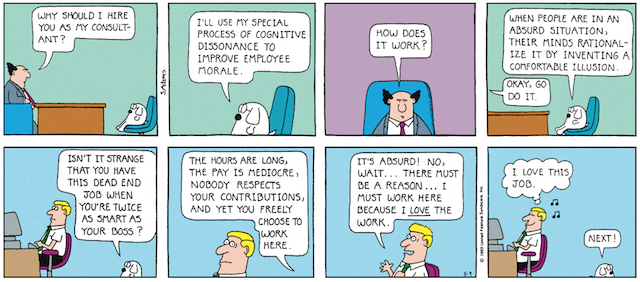

Dilbert cartoon by Scott Adams

We have the mistaken belief, I think, that we are in essence a rational species. While there is no question in my mind that we are a rationalizing species, they are not at all the same thing.

We seem to cling to the longstanding myth that our supposed intelligence was a differentiating factor that enabled us to evolve in a radically different way from other species. The argument is that our ability to think things out has given us a competitive advantage evolutionarily.

Nothing, I think, could be further from the truth. We are not so much homo sapiens as homo cogitatus, the species that churns things over in its brains, fruitlessly trying to make sense of them. A new line of study argues that it is our instincts — in other words our biological and cultural conditioning — that determines what we believe and do. And that rather than using reason to make decisions ‘rationally’, we evolved rationalization as a means of explaining these decisions, after the fact, to others.

Why would we want to do this? Because we are a pretty feeble species individually, and need the “wisdom of the crowd” to be able to survive and thrive amongst faster, stronger predators and more resilient creatures with better survival tools (claws, fangs, wings etc). Language and reasoning, this line of thinking asserts, didn’t develop to enable internal sense-making monologues but rather to enable the conditioning of other humans to do what we do. Language and reasoning are too slow and too abstract to be of any practical personal use in wild places, but they are very effective tools for domesticating and controlling the behaviours of others, so that the tribe works more or less in concert, and hence can accomplish what no individual ever could. This is the real reason, I think, we evolved as a “social species”.

So, when we rationalize our (past) decision and convey that to the tribe, and when the other tribe members do likewise, there can be a convergence in the collective conditioning of the group. Without this, I would guess, our species would almost certainly have gone extinct.

Reason, or rationalization, is essentially a process of judgement, of justification for past actions. A lack of ability to justify actions to the rest of the tribe means that the tribe will use its shared justifications for its past actions to condition you away from your ‘unjustified’ behaviours and beliefs towards its justified ones. There is nothing rational about this — it is probably more emotional than intellectual. It is rather a rationalization, one that, by influencing others’ conditioning, will influence future actions of the tribe. That’s just how human groups appear to function.

This is not all that different from the behaviour of a wolf mother who demonstrates to her cubs what is and is not safe to eat, and who nips at them if they behave in ways that she ‘knows’ are dangerous or harmful. We just use rationalization to conduct this conditioning, using language instead of our teeth.

In fact, there’s lots of evidence that our beliefs and behaviours are so instinctive (rather than ‘rational’) that when we are asked why we believe something or why we did something, we have to pause and invent a reason — ie we rationalize our beliefs or behaviours only when we have to. Of course, if our madly cogitating brains are unsure about whether what we just thought or did is ‘justified’, we may engage in some internal dialogue to rationalize and justify it. But all that stuff happens after the deed is done, and only when we think rationalization may be needed to explain it to another human.

So what does all this mean for the way in which we collectively make decisions, and specifically how we make decisions that affect the multiple crises and collapses we are currently facing?

A recent essay by Caitlin Johnstone, a woman whose inexhaustible energies and rigorous research and powerful articulation of truths contrary to popular wisdom I immensely admire, might be useful to look at to ponder this question. Caitlin writes:

The prospect of a large-scale awakening of human consciousness and radical transformation of the way humans behave on this planet may sound lofty and impractical, but the way I see it our species has trapped itself in a situation where that will either happen or we’ll go the way of the dinosaur. Every species eventually hits a point where it either adapts to changing situations or goes extinct, and as we accelerate toward nuclear war and the destruction of our biosphere it seems fair to say that that crucial juncture is upon homo sapiens now.

If we are in fact a rationalizing and not a rational species, what are the chances of such a “large-scale awakening of human consciousness and radical transformation of the way humans behave”? I would suggest, sadly, that they are pretty much zero. We don’t think logically or rationally. We react instinctively and in accordance with our conditioning, and, only if necessary, rationalize to justify that conditioned behaviour after the fact.

Of course we would love to believe otherwise, and we very often rationalize what has happened to leave open the possibility of such Hail Mary transformations. We believe what we want to believe, not what is rational. That is human nature, how we have evolved for a million years.

But believing something is possible does not make it possible.

So what then? Do we just give up and resign ourselves to painful and utter collapse?

My answer would be yes and no. I’m not a believer in salvation, from above or within or from technologies or gurus. There is overwhelming evidence, if we dare face it, that we have long passed the point of averting or even significantly mitigating or slowing civilizational collapse. And I think just doing our own individual part to behave more sustainably is, while completely consistent with the conditioning we ‘progressives’ have been inculcated with, utterly futile.

Still, there are some groups that are looking at how we communicate and act as tribes and groups and other small-scale collectives, and how facilitating each other might make such collectives more effective. I’ve written before about Citizens’ Assemblies (like those demanded by XR to address climate collapse), and (Bohm) Dialogue, as processes that might help us avoid the more unhelpful cognitive biases and emotional traps that collective thinking and decision-making can fall prey to.

Complexity theorists like Dave Snowden and Cynthia Kurtz have developed tools and processes that try to add rigour to the processes of collective dialogue, deliberation and decision-making. Cynthia’s model entails:

- the collection and telling of stories of direct personal experience representing a diversity of perspectives and experiences;

- the interpretation of the stories by those who told them, responding to questions and inquiry;

- catalytic (inductive rather than analytical) pattern identification and exploration; and

- narrative group sensemaking (collectively asking: What does it mean? What is believable? What actions make sense?)

Can such a process, at least at a local scale, short-circuit our propensities for cognitive bias, for believing what we want to believe rather than what is true, and for rationalizing what we believe instead of challenging it in light of other information? Can we tinker with our individual and collective conditioning?

My answer would be that theoretically, yes, it might be helpful to at least try using these techniques. But in my experience, no matter how rigorous the process, a lot of people not directly involved in the process will end up dismissing the ‘consensus’ that comes out of this process if it doesn’t align with what they already believe. We’ve seen this in referenda that have repeatedly rejected proportional representation and other forms of electoral reform, even when the assemblies that came up with the reform proposals were unanimous in approving them.

If XR’s Citizens’ Assemblies were actually employed, and if they, after lengthy facilitated study, recommended a massive change to our entire economic and regulatory system involving a radical shift and reduction in production and consumption of goods and services, how likely is it that these recommendations would actually be implemented, even if they weren’t subject to government or citizen ratification? Not likely at all, I’d guess.

So, as much as I like group deliberation processes like (some forms of) Bohm Dialogue, Citizens’ Assemblies, and Participatory Narrative Inquiry, and as much as I believe they can point us towards better collective decisions, I think their use is largely limited to small-scale applications where everyone affected by the process was involved in the process.

Expecting more than that from them, I think, is, well, unreasonable.

Thanks to Stefan and Susan at GreaterThan for the prompt for this article, with their newsletter asking “What if reason is simply the justification we give each other for the things we do or want to do?” And also to Paul Heft for his thoughts on Caitlin’s column.

I agree with you and the history of modern civilization supports you, too. If it had been possible for us to have been reasonable about the strategies necessary to avoid collapse, then it would have happened long ago when those strategies could have been far simpler and easier to implement.

Nuclear war is certainly one way that civilization could collapse and it’s more probable than most people think. Climate change, reductions in biodiversity and all the other symptoms of overshoot will doom civilization too. Many tipping points within our inherently fragile global market economy could instigate the collapse of modernity at any time, even before the ecosphere is destroyed.

The reasonable and prudent thing for small groups to do (including groups as small as families) is to prepare for doom in all its various incarnations, including nuclear war. The prudent steps to be taken are not that difficult to reason out. The hard part is finding the courage to make the first step.

Fully agree.

Rationalizing after the fact is indeed what we do and what we have to do. No choice here.

Harmony and unity of purpose in the tribe demands it.

It doesn’t work so well in a global, energy guzzling, biosphere destroying civilization of 8 billion tribal members. How can one make such a colossal tribal system function in a rational, self-preserving way?

You can’t. It’s not in human nature. We haven’t evolved to be able to deal with such a monstrous tribal system.

But at least you can have small cohesive groups happily rationalizing and thinking that as a small homogeneous group they can survive the coming cataclysm. I don’t think they can. After the nukes or species termination epidemic have done their job there isn’t much rationalizing left to do.

This is an interesting piece, and I agree with much of it. I think I was first introduced to the part of the brain that does the “rationalizing” in the Michael Gazzaniga book “Who’s in Charge” (where he talks about his studies of split brain patients).

But I think there’s a bit of a hole in your argument. When you say that one’s rationalization can influence others’ conditioning, it seems to me that for any such rationalization to have influence on another’s actions, that other must “rationally” accept it.

I think it would be safer to assert that language and reasoning were evolved to facilitate our transition into becoming tribal/social animals, therefore overcoming our weakness as individuals standing alone.