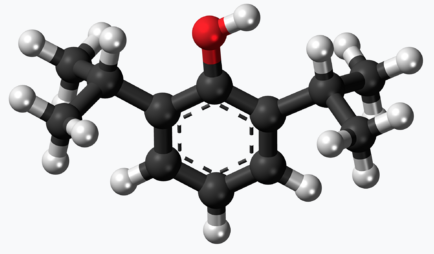

propofol molecular structure, per wikipedia, CC0

Last week I went to the hospital for a colonoscopy. I was given a general anaesthetic called Propofol, a relatively new (1990) drug that has received a lot of publicity, and is in wide-spread (human and veterinary) use everywhere on the planet. Although there are always risks with anaesthetics (notably drop in blood pressure and slowing of breathing), it takes effect very quickly (no more “counting down”), and recovery is also extremely fast, leaving patients often feeling “well rested” rather than the groggy feeling of other anaesthetics. But there’s a suggestion that the well-rested feeling is illusory, as the sleep it induces is “not a clean, clear sleep“. It also suppresses memory recall.

Surprisingly, although it requires expert care to administer it properly, any doctor can obtain and administer it. It was allegedly administered by Michael Jackson’s private physician as a sleep aid, purportedly leading to Michael’s death.

The anaesthetic serves a number of functions essential for surgery — not only sedation but also numbing of sensation and muscle relaxation (temporary paralysis).

It is also an essential part of the process used in Canada for medically assisted death. And it’s been used extensively on CoVid-19 patients in ICUs who require ventilators.

In Europe and the UK it is illegal to export the drug to the US, because some states there have it on their list of drugs used for executions.

An occasional side-effect of the drug is priapism.

I went into the procedure last week curious about whether I would have any sense of time passing, of dreams, or of memories, when I awoke — all part of my larger curiosity about the nature of time (an illusion constructed in the brain in the attempt to categorize and ‘make sense’ of sensation?) and ‘consciousness’ (a misinterpretation of the brain’s categorizations of its sensations as ‘real’ subject-object separation?).

It was, I have to say, a non-event. One second I was looking at the monitor that I’d clipped onto my index finger, and the next I was listening to what two people outside my curtained-off area were saying. There was no sense of having lost ‘consciousness’, or regaining it — it felt as if I’d been fully awake the entire time, and that nothing had happened. There was no sense of any time passing between the index finger moment (which was in the colonoscopy operating area) and the listening-to-voices moment (which was back in the prep area where my clothes had been left, a short trolley/gurney ride away).

It was as if the two moments occurred as a continuum, with nothing in between, with my brain transitioning from the finger-thought to the voices-thought, and trying to make sense of it. And immediately thereafter, the nurse came in and told me to get dressed, and that my friend David was there to drive me home (thanks David!). I felt rested, energized, and sprang out of the bed, dressed and left.

But forty minutes had elapsed, according to the clock, and presumably in the perception of the people working in the hospital. Forty minutes with no apparent transition, no nodding off or waking up, no continuity, or discontinuity.

For forty minutes, there was simply no me. The body I have always presumed to inhabit did perfectly well without me, though I’m sure the staff were watching and would have taken steps if this old body signalled it needed assistance. This body didn’t ‘miss’ me at all.

We believe what we want to believe, of course, and perhaps my sense that this body was telling me, in its own quiet way, that it didn’t need ‘me’, this presumer-of-consciousness — not ever, not at all, thank you — is overstating the lesson. But wow, it sure felt that way. It sure feels that way.

This body, in the past hour (if time were real) has gone and made tea and a snack, turned on the fireplace, written some things on a ‘to do’ list, all while its fingers hunt-and-pecked its way through this blog post. This body’s brain is trying to make sense of all this. It’s trying to make or tinker with a model of reality that is ‘good enough’ to explain what happened, and when and where and how and why it happened. ‘I’ am full of theories on the matter.

And of course, as ‘I’ present these theories, ‘I’ take credit for all these mental calculations. Worse, I have the gall to suggest those calculations are worthless after-the-fact rationalizations of what this body was going to do anyway. I am sure the body, if it had a ‘mind’ of its own, would suggest that perhaps ‘I’ should just STFU about all of this then.

Though I doubt very much that ‘I’ would listen.

May be what you “lost” for 40 minutes was the self you pretend not to have? :-D

Propofol is great stuff.

Practical for anaesthesia and for research into consciousness.

Truly a magical molecule.

I once experienced the same kind of “non-event” when I was a young boy. I remember an older boy walking up to me and being very angry about the pebble I had thrown at him. I was instantaneously transported about 50 feet away and I found myself walking toward my home.

The older boy had slugged me in the face and knocked me unconscious. I experienced absolutely nothing in the interval between being hit and coming to a bit later. I have always believed that death is just like that experience, except it never ends.

Lots to ponder along the lines “where does consciousness go during sleep or under anesthesia?” Might be the wrong question. Either way, consciousness returns rather reliably after a night’s sleep or after a drunken bender (or various other drug experience). The presence or absence of transitions doesn’t concern me much, though their absence can be jarring. What concerns me more are dissociative episodes where consciousness splinters or hives off, leading to a feeling of unreality to the world and falseness of the self, like a fiction one inhabits yet observes somehow. Clinicians would likely have a diagnosis rather than a philosophy, but investigations into drug therapies designed to invoke those experiences echo shamanic practices developed over millennia. I’m relatively agnostic about it but recognize a general trend toward breaking out out of the mechanistic mindset, which some think of as reenchanting the world.

@Brutus

If you want some fairly exhaustive and recent report on consciousness going “on and off” I would suggest Sizing up Consciousness Towards an objective measure of the capacity for experience.