It seems to be basic human nature to assume the future will be like the present, “only more so” — We expect current trajectories (and even “hockey stick” accelerations) to continue.

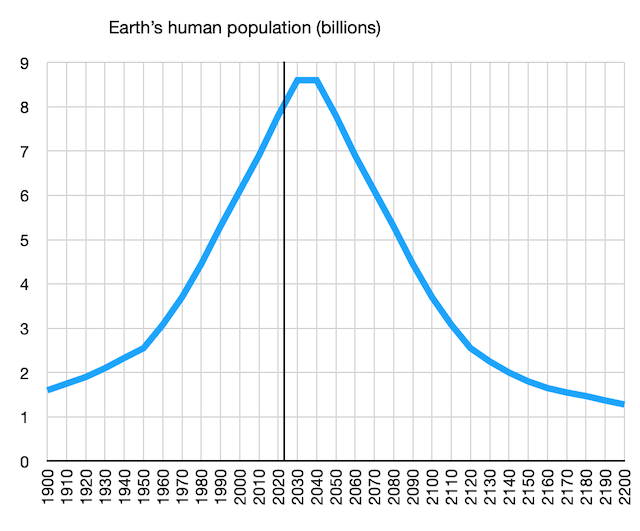

Unless there are constraints — limits — that is not an unreasonable expectation. But there are usually constraints. The constraints for our planet, and all life that depends upon it, are the finite amount of land, water, air, soil, energy, and natural resources that can be exploited. For billions of years Earth has witnessed cycles of self-organizing life achieving equilibrium, followed by collapses — global extinction events. These cycles tend to follow a normal curve like that depicted above — a first appearance, then little change for a long time, then sudden accelerating growth, then decelerating growth as limits are reached, then precipitous decline, and then slow decline for a long time, leading to extinction.

To us, such a curve has five perceived stages — slow, fast, slow (at the peak), fast, and slow, in that order. We are now at the third stage, at the peak, at the cusp of what Hemingway described as the “slowly, and then all at once” point of decline. The point at the top of the roller coaster when time seems to stop.

We can appreciate that conceptually, but that doesn’t allow us to actually imagine, anticipate and accept as inevitable the current civilizational collapse and great extinction event, and what they will lead to. What they will lead to (at first “all at once”, but then more slowly over a few centuries), is human societies and planetary ecosystems that would be unrecognizable, even unimaginable, to anyone alive today. And then further slowing before the final human departs the scene, tens of thousands or even a million years from now.

This is the simple reality of how collapse inevitably happens, and it is both astonishing and fascinating that we cannot get our heads around it. It defies all our conditioning about how to think, behave, and process information.

Here are just a few of the things that we unthinkingly, across the political spectrum, seem to take for granted now, things that make no sense when one looks at them through the lens of the near-imminent and unavoidable collapse of our civilization and global ecosystems:

- Growth is good: I keep reading articles that talk about economic ‘recovery’ as a good thing, and slowdowns as a bad thing. What will it take before we realize that growth got us into this mess, and de-growth, as equitably as we can manage it, is what we should be measuring as ‘progress’ and striving for?

- Someone has to be to blame: “Well, yes, Billy accidentally blew up the house and killed the rest of the family with his chemistry set, but, you know, his teachers, and the manufacturers of the chemistry set, and of course there were underlying factors…” It’s time to grow up and stop assessing blame. It gets us nowhere.

- Dwelling on the past: Kind of related to the blame game, we seem obsessed with anger and guilt over past atrocities, stirring them back up and refusing to let go of them. Of course they were outrageous, devastating, traumatizing. Tell the truth about them, give and receive apologies, declare an intent to learn from the errors and not repeat them, ask for (and offer) forgiveness, and then move on. So many people spend their lives living in, and reliving, the past. Such a waste.

- A politics of hatred, anger, fear and war: Our world is fucked, we’re living in the shadow of collapse, loss, suffering, and death. And what is the news full of, and our attention focused on? Fear-mongering, war-mongering, hate-mongering, propaganda, over-filled privately-run prisons, hopeless, brutal refugee internment camps, bloated militarized police forces, and endless wars. It’s fucking insane. It’s like we’re all facing an imminent firing squad and we’re fighting each other over who deserves the last cigarette. How did all our reward mechanisms get so utterly screwed up? We’re better than this, surely.

- Capitalism, debt and money as the only way to run an economy: Most economic decisions continue to be made based on maximizing profit for designed-to-be-psychotic corporations. The same system externalizes (doesn’t count) ‘costs’ that are all about sustaining the essentials of basic human and natural wellbeing. This system rewards absurd risk-taking, lying, cheating, and fraud. It has 99% of the population in debt to the other 1% just to make basic ends meet, debts that for the most part can never hope to be repaid, even if collapse weren’t looming everywhere it hasn’t already occurred. And most of us in one way or another worship money, which is simply the tool used to create more debt, and with it, more ‘growth’ (accruing entirely to the richest 1%) and more suffering. There are many better, fairer, simpler ways to transact with each other, that require none of these things. None of these elements of the capitalist religion makes sense in a collapsing world.

Even if we were to rid ourselves of these obviously dysfunctional (in the context of collapse) beliefs and systems, we would be left with the existential question about collapse: What does it mean? — that despite everything we have tried so valiantly to do, our civilization, our species, and most of the species of our world are all dying.

It’s a question that kind of defies answering, at least to the extent we find the value of meaning in making sense of what we have done, and what we are doing, and informing what we might think of doing next.

Consider the analogy of a single human life. From the moment we first conceive of ourselves as separate, we tend to imagine our life’s trajectory as being without end, without demise, and live until our life’s final days as if somehow we might never die. We may buy life insurance, but that’s for someone else, and we hardly relate it to our own death.

So what does it mean to accept that our civilization, our species, and most species of our world are all dying? What does it mean to contemplate that we, alive today, are eight billion of 110 billion humans that have ever lived, and that one day not so far away there will only be scattered tribes of humans, and, eventually, after that, probably no humans at all?

While I think they’re off on the timing, Guy McPherson and the NTHE crowd have tried to embrace this realization. Their approach has been to look at it somewhat as one looks at a loved one’s diagnosis as having an imminent terminal illness — with a mix of grief, compassion, and preparedness.

That may make sense, but rather than just acknowledging the reality of coming death, it seems to me it would make more sense to take stock of, and celebrate, our lives. To optimize how we, as a species and culture, spend each moment of our remaining time, rather than just striving to continue the madness that got us into this mess a little longer. To make the best of what time we have left, together and in harmony with, and perhaps even in service to, the more-than-human world that is harder hit by collapse than we are (though they will likely outlive us).

| What might be our collective statement, to the world and to each other, as we contemplate the collapse and extinction of our cultures and our species? Not as a greeting or warning to aliens. Not as a mea culpa to the more-than-human world. Not as something to be remembered for (by whom?). But, instead, as a tribute, recognition, and collective thanks for what all 110 billion of us who have ever lived on the planet, all of us doing our best (if somewhat cluelessly), would like to acknowledge to each other, human to human, across the world and across time. |

Something to think about.

Dave, I personally don’t think that there is a need to pay tribute and say thank you for the poor fellow members of this species that have already come and gone.

We’ ll soon follow them. As “out of existence” by then, I wouldn’t even know it whether some of the still alive and kicking colleagues paid tribute to my fleeting “heroic” existence. It can possibly serve some feel-good function for the individuals that pay the tribute. It makes it look like there is somehow meaning to our brief existence.

Evolution and the MPP were never “aware” that the game they were playing was done on a finite planetary field. No idea of boundaries. When we came along we learned some science and enjoyed ourselves with the obscenely rich stash of high-density energy and eventually (a bit late in the game though) the boundaries became all to visible, at least to a few individuals who managed to skip the denial of this reality. But the colossal party we were throwing by then was just to good to end. Boundaries? What boundaries? We don’t need no boundaries to spoil the fun. So, we’ll party on till the boundaries come crashing down on us.

No there is no need. But we should do it anyways, just to be kind to each other. And the tribute is not to other individuals, but to our collective species, undivided. It is a ‘making-peace’ process, for a species that has always yearned for peace but never been terribly good at it. Not our fault — our species was fated to be haunted by demons of our own imagining and racked by emotions like guilt, shame, and anxiety about invented pasts and imagined futures that no other creature has had to contend with. Under the circumstances, we did our best, and though that was not nearly good enough, it was, I think, a valiant and exhausting effort. As players in the game of life we were terrible failures, but we were earnest and well-intentioned. We tried. That, IMO, is enough, all that matters.

Thanks Dave. It’s always appreciated to discover one more little island of sanity in an otherwise insane world.

Thanks Tristan. Your JustCollapse site is an outstanding resource. The first page of your ‘little book’ is especially powerful, as its down-to-earth, humble, pragmatic approach is refreshingly different from the idealistic, impractical approaches taken by so many other organizations.