Just a reminder that I am not a health professional and nothing in this post should be construed as health advice. Every body is different.

It’s been a while since I wrote about the process of self-managing one’s health.

I got interested in it after realizing that doctors, especially in today’s anonymous, revolving-door walk-in clinics, can’t possibly hope to know your body well enough to give you a competent diagnosis of what ails you, or what you should do about it, especially in the allotted 10-minute consultation period.

Still, for some reason, most people go to the doctor or hospital completely clueless as to what’s wrong with their health or what some of the treatment alternatives might be. “I’m sick, doctor; heal me!” Intelligent health care is a partnership between health professionals and patients. Like marriage, or business, it usually fails if one of the partners is only intermittently involved.

I started a health self-management program back in the eighties when I first had symptoms of kidney stones. Those were pre-internet days, so research involved reading health compendia, encyclopedias, and making visits to the library. I passed three stones between 1990 and 2004, and most of the advice I got was self-contradictory. That was 20 years ago. I was dealing with bouts of debilitating depression, severe job stress, and chronic back pain in those days. Anti-depressants (no surprise) didn’t work, and left me brain-fogged and exhausted. My weight was a record 170lb. I kept resolving to start exercising, but I just wasn’t up for it. I did become vegetarian, finally, and that seemed to help, but mostly, when it came to my health, physical and psychological, I just felt helpless.

Two years later, just as I was starting to feel better (six months of daily exercise was dramatically improving my mood), I got some terrible financial news (a result of my employer’s incompetence) and went into a tailspin. Horrific anxiety attacks, radical (40lb) weight loss, and then severe rectal bleeding. By then we had the internet, so I knew I had ulcerative colitis. It was confirmed, they did a colonoscopy, and, against my will, the specialist put me on steroids, which made my symptoms much worse and almost killed me. For weeks, I simply wanted to die, and to never wake up, just to end the interminable pain and insomnia.

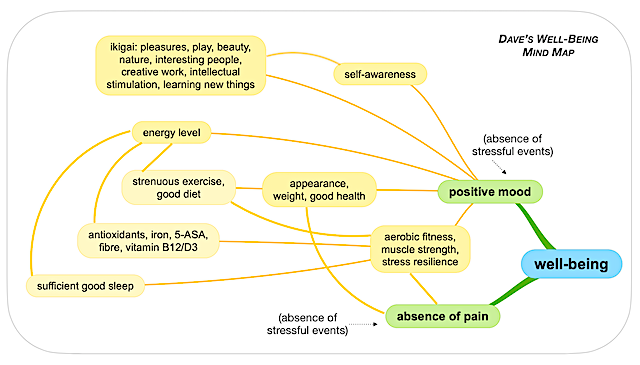

I resolved to never again be helpless when it came to my health. Based on a weight-loss (!) book by the late Seth Roberts, in which he explained how keeping a rigorous daily journal helped him identify the factors that affected his weight and health, I began to track all the variables that I thought might contribute to my health (physical and psychological), and correlate them to my subjective assessment of my overall (a) physical health, (b) physical fitness level, (c) stress level and (d) overall happiness. I tracked the correlation between each of these variables and the four assessments, and between the four assessments. Seth liked the process I was using and we corresponded a fair bit about it.

I used a rather involved statistical process to try to avoid biasing my assessments. This meant tracking not only all the daily correlations, but also the correlations between, say, some drug or vitamin I was ingesting, and my health and happiness assessments one, three, and seven days later. I also used multivariate regression analysis to try to eliminate coincidental correlations and identify precisely which variables were most contributing (positively or negatively) to my health. Having taken a lot of courses in statistics really helped. Including the fact that those courses taught me when and how to be skeptical of statistical results!

It was, and is (I resume using it whenever my health takes a turn for the worse) a laborious, frustrating, and imprecise process. But the payoff to me has been enormous. It confirmed for me the worse-than-uselessness (in my case) of steroids as a colitis treatment, and the significant effectiveness of specific NSAIDs. Of 36 variables that had been suggested to me as contributors (positive and negative) to my health during my bout with colitis, I found only eight consistent, statistically significant correlations. Over the past 17 years I have had three very minor ‘flare-ups’ of colitis symptoms, all of which were quickly resolved by increasing my NSAID dose. A colonoscopy earlier this year showed that my colon is in remarkably good health, though my gut flora will probably never fully recover from misguided high-dose tetracycline damage that dates back to my childhood.

In the process of tracking this data, I discovered that, according to reputable research organizations, less than half of the ‘supplements’ (other than vitamins) being sold to us for every ailment under the sun actually contain the ingredient on the label unadulterated with other unlisted ingredients and pollutants like mercury, lead, and arsenic. It’s a disgrace that this industry is pretty much completely unregulated, but, hey, we live in an age of deregulation. If you rely on supplements, caveat emptor.

The analysis of the data suggested that stress (and my incapacity to deal properly with it) was the catalyst (ie predicted the onset of, but may not have ’caused’) my colitis, and probably of my depression and anxiety as well. But it also suggested that nothing that I have tried worked effectively to reduce my levels of stress or my stress coping ability. When there has been less stress in my life (like most of the time these days), my physical and psychological health have been good, and vice versa. None of the ‘stress-busters’ I tried — drugs, meditation, therapies etc — helped at all. That’s just how this particular body seems to work. But at least I know.

Because of the caveat I started this post with, I’m not going to list the variables that seem most highly correlated with my recent excellent health. Every body is different, and the point of this post is to encourage people to keep a journal, track the data, and trust the process to point them in the right direction for them.

You can probably guess at some of them, though, again, they’re not for everyone. I’ve been a vegan (balanced, varied, plant-based diet) for a long time now, and I run four miles a day. I take eight vitamins/minerals/maintenance drugs every morning, all of which have been vetted for authenticity and purity. Periodically I sit down and talk through how I’m dealing with stress, and with the doom-scroll etc, with someone I trust. I still get stressed easily, but now I am more aware of the fact that I’m getting (unhealthily) stressed, and that seems to help reduce the intensity and duration of the stress. That’s what works, apparently, for me.

I also get a comprehensive blood ‘panel’ of tests done, twice a year, and can immediately access the test results, and comparatives with previous tests, online through my electronic health record. This gives me an ‘early warning’ of many potential health problems, that I can work on promptly.

Health self-management is not a panacea, of course. I work with my doctor and my physiotherapist. Sometimes, the process doesn’t work at all (four years ago, I developed early signs of Depuytren’s Contracture, for example, and all the rigour in the world trying to find a treatment for it hasn’t helped, though it’s not really problematic and has gotten no worse).

The elements of effective health self-management are, then:

- Doing research to identify illness-preventing activities (vitamins, diets, exercises, vaccines etc) that have been shown in rigorous independent scientific studies to reduce the likelihood of health problems for someone of my age and with my genetic background and lifestyle. And pursuing those activities.

- Getting periodic non-invasive health assessments, such as blood ‘panels’, to surface possible emerging health problems.

- Doing research to self-diagnose health problems as they arise, and then confirming those diagnoses with a health professional.

- Identifying possible treatments to address known health problems, and then, using a journal, data collection, and statistical analysis process, assessing which treatments are actually helping, and discussing these with a health professional.

I’ve been very lucky, health-wise, all my life; my genes are good and my lifestyle is, finally, healthy. I feel and look much younger than 72, which I turn next week. Health self-management doesn’t entirely account for that, but it’s surely a factor.

Happy Birtday for next week Dave!

Love your thoughts

(I suspect there’s a self portrait hanging in the attic of your apartment somewhere)

This is nice for you and I’m glad you were able to get on top of it, but most people don’t have the discipline or personal self management skills, education or time and energy (and money)to conduct such an anlysis. I’m afraid this reads a bit like one of those self-help books by “famous psychologists” that essentially tell you to pull yourself up by your bootstraps. Reading them gives you a bit of positivity and a sense of agency, but for most folks the obstacles are too many.

Maybe AI will be of help with this

Thanks Mark.

Theresa, you may well be right, though I do know of several people who have employed a simplified version of this process to at least improve their capacity to self-manage their health and to be a true partner to their health professional. I think we’re years away from AI being of any value in this endeavour (though I suspect your comment may have been meant in jest). I’ve played with ChatGPT, and while it can provide a coherent synopsis of “prevailing wisdom” on health issues, sometimes that “prevailing wisdom” is pretty questionable, and in any case, every body is different, and even the proposed “personalized AI” will never be able to know enough about our personal bodies to be of much use in creating and individualized health program.

I’ve heard similar comments about diet, which is an integral part of any health program and particularly a self-managed one. Most people will never be willing and able to create and follow a very healthy diet customized to their body’s needs, but even a bit of knowledge and some small improvements can lead to significant improvements in health. Of course, we don’t have any choice in that; we will either make those changes or we won’t, and exercising ‘free will’ plays no part in that.