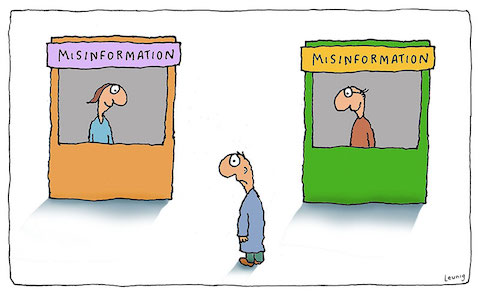

cartoon by Michael Leunig from his fans’ FB page

If you wanted to pick someone to point out the danger of stories, you probably couldn’t find anyone better equipped for the job than a lifelong book reviewer.

In this week’s New Yorker, reviewer Parul Sehgal provides just such a critique, and it’s a masterful piece of writing. Parul starts by reviewing the ultimate storytelling story, that of Scheherazade’s nightly bewitching tales that saved her from being murdered by the king, as he repeatedly deferred her execution to hear the next instalment. She then outlines some of the writers who have drawn on the myth, and some of the writers who have warned about the dangers of stories, especially when they extend beyond the confines of established fiction. She writes:

[Storytelling] is the realm of playful fantasy (but also the very mortar of identity and community); it traps (and liberates); it defines (and obscures)… Storytelling is what will save the kingdom… We are persuaded more by story than by statistics; we recall facts longer if they are embedded in narrative; stories boost production of cortisol (encouraging attentiveness) and oxytocin (encouraging connection). We are pattern-seeking, meaning-making creatures, who project our narrative needs upon the world…

And if a story betrays us? The solution, it seems, is to cast about for a better one.

But stories also lull us into a false sense of knowing, continuity and certainty. “How inconspicuously narrative winds around us,” she writes, “how efficiently it enables us to forget to look up and ask: What is it that story does not allow us to see?” When we get so caught up in following the plot, we can lose our curiosity about what is not being said.

She summarizes Peter Brooks’ book Seduced By Story, which warns of a “‘narrative takeover of reality’ — an evocation and understanding of the world which is purely narrative, which cannot see that living and telling might be different things.”

Narrative, she says, has wormed its way into business (marketing, PR, brand ‘stories’ and ‘reputation management’), into law and medicine, and, of course, into political discourse and journalism (including propaganda, mis- and disinformation, and censorship of unpalatable story elements that send nuanced, complex and hence undesirably confusing messages to the stories’ ‘consumers’).

She cites Jonathan Gottschall’s book The Story Paradox explaining how stories invoke “unconscious obedience to the grammar” of the story: “Details are amplified or muted. Irrelevancies are integrated or pruned. [And] each decision [on what to include, reword or exclude] is an imposition of meaning… an exercise of power.” The rewriting of history, the drafting of obsequiously distorted case studies and biographies, the whitewashing of memoirs are all such exercises of power. Art, music, and much poetry, on the other hand, do not lend themselves to being conscripted to the service of the author, since, as Parul cites Jason Farago as pointing out, these arts provide “no assurance of closure or comfort”.

An aversion to, and distrust of, story is nothing new, she asserts, noting Plato’s urging that all storytellers be exiled as manipulators, and the non-narrative nature of much early literature, including the Quran. EM Forster, she says, described stories as unseemly, the lowest literary form, the “tape-worms” of literature with their insistence on order and sequence in time. And Rebecca Solnit, she says, claims stories hem us in and “prevent us from seeing or believing in the possibilities for change”.

Midjourney AI’s imagining of someone paying attention to “the pure immanence of a moment”; my own prompt

And then she gets into the real poverty of stories, beyond their obvious dangers:

Instead of trying to resist story, perhaps we should try to be a better custodian of it. [The book] Braiding Sweetgrass [explains] how every story invariably displaces some existing body of knowledge. What forms of attention does story crowd out?… Much of life is the narrative equivalent of dark matter…, what writer Lorrie Moore refers to as “unsayable life”… That snarl of time, thought and sensation — uncombed experience — is what theorists call “the unstoried self”, what Annie Ernaux calls “the pure immanence of a moment“… That unstoried self understands a great deal in its commotion, in its inability to keep anything compartmentalized, and it loses something [when squeezed into the constraints of storytelling]…

[Our lives are not our stories; they are, rather, what Elena Ferrante in her book Fragments calls] swarms, ‘Frantumaglia’, jumbles of fragments. A swarm possesses its own discipline but moves untethered. Nothing about the notion of a swarm comforts or consoles. It doesn’t contain, like a story. It allows — contradiction, dissonance, doubt, pure immanence, movement, an open destiny, an open road.

So beyond the seductive, subversive dangers of stories, which are obvious to anyone with a modicum of critical thinking skill, the real tragedy of our addiction to story and narrative — all the stuff we see on all the screens (think about that word screen and its connotations!) to the point stories now utterly dominate our attention — is that we have largely forgotten how to actually be in the world, and how to focus our attention on something that doesn’t have a ‘thread’ of time and meaning attached to it. Language and story, to a large extent, are what, I think, have untethered us from the natural world and from our biophilial connection to the rest of life on earth. We are not our stories, nor are we contained by them.

As we face the collapse of all the systems propping up our exhausted civilization, this loss of ability to see and appreciate the pure immanence of a moment, and to actually be in the world, rather than in our stories about it, is perilous. Most of what we think and believe and do is a product of what we pay attention to, and if all we are paying attention to are the stories about our world, we are in for a miserable time of it. Our stories, with their ill-fitting morals and unsatisfying plots, will not help us through collapse.

Thanks for this Dave, very useful. It’s easy to become trapped into the ‘we need another story’ or ‘a new myth’ approach to the ecological crisis. I work within the Environmental Humanities, with academics from English literature, creative writing, religious studies, philosophy and history, and – unsurprisingly – the importance of story-telling and narrative is hard to escape. Indeed, I’m not sure we can escape it, but there is some useful unpacking of the dangers and harms here. Appreciated.

Stories. Use with care.