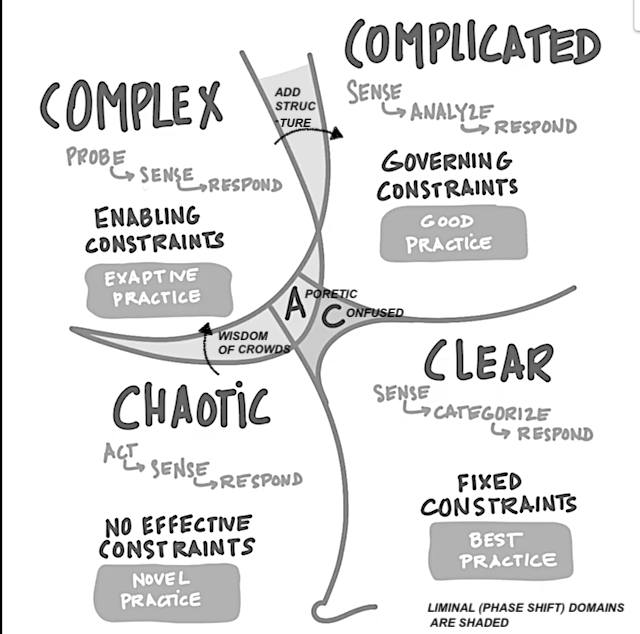

Dave Snowden’s Cynefin framework (2021). Adds liminal domains, points of uncertainty or paradox, notably the aporetic domain, from whence, notably, NZ’s Jacinda Ardern chose to cede decision-making authority to health experts as being better equipped than politicians to determine the most sensible next steps to deal with the pandemic, buying time in a chaotic period of crisis and keeping options open.

Chaos, in its social rather than mathematical sense, refers to the absence of effective constraints.

What that means in a human political, economic or social system, is that no one pays attention to any accepted rules governing the system, which are therefore unenforceable. In ‘chaotic’ economic and political systems that means oligopolies, bribes, extortion and other ‘officially illegal’ activities may prevail without limit. In some cases, organized crime actually substitutes its own laws, rules and constraints, to deal with the chaos.

What I think we are starting to see this century is gradually increasing levels of chaos in much of the world. In fact, the increasing number of the world’s economies that are dominated by oligopolies and organized crime might actually be a little less chaotic than countries that are still trying to play by the rules. In countries ruled by oligarchs and organized crime, you at least know who you have to pay off, and how much, and the consequences if you don’t. That may be despotic, but it isn’t chaos.

If the system collapses to the point that even oligopolies and organized crime cannot maintain order, then you have at least short-term chaos and possibly anarchy. Immediately, in order to get essential things done (like food and energy distribution), ad hoc systems will emerge. Dmitry Orlov has described how this happened with the fall of the Soviet Union and the collapse of the ruble: A system of commerce emerged based on a combination of tribute (giving to those you respect), barter (trading reciprocally for something of value), gifting (giving without expectation of compensation), and scrip (effectively, IOUs signed by someone known in the community that become a replacement ‘currency’ that others agree to accept). Such systems, of course, do not scale.

In political systems, a descent into chaos means that, especially in the early stages of collapse, and largely thanks to ubiquitous corruption and broken electoral systems, those in power may not need to have the support of citizens to stay in office nearly indefinitely, and they are hence free to ignore the citizens and their wishes and needs, other than propagandizing them through the media. And they can accept money for implementing laws and regulations written and paid for by moneyed interests.

But that tends to only last a short while, as citizens lose respect for these “officials” and start to disobey their laws as well. And then, if the police and others charged with enforcing the laws become as disenchanted as the rest of the citizens, political chaos is likely. That means, among other things, that people will stop paying taxes, will overtly disobey laws and rules set by officials they no longer respect, and that there will be a huge jockeying for power and authority among those seeking to fill the power vacuum. Politics and economics, after all, only function when there is broad agreement to abide by the rules; coercion and propaganda can only achieve so much in its absence. Currencies, in particular, are based in trust that they can be redeemed for their face value, and when that trust is lost, the currency quickly becomes worthless, as citizens of many countries can attest.

Once you get political and economic collapse, and these systems devolve into chaos, social collapse may ensue, as people take things into their own hands and refuse to trust anyone else. As Dmitry explains, social collapse and social chaos are disastrous, as they preclude everyone’s attempts to restore some sense of order. Civilizational collapse then becomes pretty much inevitable.

My sense is that this situation is well advanced in many poorer countries, and becoming much more evident in many countries in the west, to the point I currently believe global civilizational collapse is nearly inevitable over the coming decades, and this will occur even without the multiple ecological crises that are compounding the polycrisis.

Once an entire civilization crumbles, collapse historically has followed one of three pathways: devolution, with the making and carrying out of decisions radically relocalized to the family, tribe or small community level (as larger and more centralized systems just cease functioning or are no longer recognized as legitimate); absorption, where the members of the collapsed societies scatter and join other still-functioning cultures, if there are any; and/or abandonment, where the citizens just ‘walk away’ from systems that no longer function and re-band together (in the same or some other location) into cohesive social groups and self-organize to create order within those groups and in relation to other groups. They then self-impose new constraints and hence achieve some sort of self-governance.

We may see all three, or some new alternatives, in different parts of the world as collapse deepens. One of our greatest challenges in many parts of the world is that most of us are completely dependent on the centralized, specialized, fragile systems of modern capitalism, such that few of us still have the competencies and skills to meet any of our basic needs without support from “the system”.

We can learn much about coping with collapse and the resulting chaos, from studying past civilizations, and from studying how those in poorer nations (and impoverished parts of more affluent nations) have already been dealing with the essential collapse of their political, economic and social systems.

Many of these collapsed societies and sub-societies have effectively self-reorganized around tribes (in the broader sense of the word: “families or small communities linked by social, economic, religious, or blood ties, often with a common culture and dialect”).

In many cases, the economies of these ‘neo-tribal’ societies are substantially what Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing in her brilliant book The Mushroom at the End of the World has called salvage or scavenger economies. During the reign of an industrial capitalist economy, salvage activities are marginalized and usually feed back into that capitalist system (eg collecting recyclable containers and selling them to commercial buyers, or selling privately harvested crops to commercial enterprises). Anna’s book, which describes how the salvage/scavenger economy works already today in parts of the world, is essential reading for anyone wanting to imagine what our post-civ economy and society might look like.

When the industrial capitalist economy crumbles, just about every activity carried out then becomes a salvage operation, since there is no longer a reliable commercial/industrial system to sell the salvaged goods to. So as Big Ag collapses (as farmers in the Great Depression found out), there is no longer a market for large volume monoculture crops, and all food and resource harvesting at every level becomes a salvage operation. You then ‘harvest’ and sell just what’s needed, just in time, to whoever near you needs it — copper for repairing broken machines for example. And at that point you give up reliance on large established markets ordering stuff in large quantities in advance, because they’ve disappeared.

We will all become salvage operators. A lot of industrial economy outsourcing and offshoring has already made much of the economy into a salvage operation — ‘independent’ truckers replacing commercial fleets, Uber/Lyft drivers, and ‘gig’ economy, offshored and outsourced work are all, in a way, forms of salvage work that currently sit at the periphery of, and feed into, the industrial economy. As that industrial economy collapses, we will all be doing salvage economy work, except we’ll be meeting the needs of our fellow community members, not those of big corporations which will no longer exist.

The issue in a salvage/scavenger economy is not “Who will buy my product or service?” but “What does my tribe/community need today, and where can I salvage it from?”

Ronald Wright’s somewhat dystopian cli-fi novel A Scientific Romance envisions what a salvage/scavenger economy might look like. But personally, I need look no further than outside my window, where I see throngs of crows, every day, thriving in such a self-evolved economy, drawing on the things humans throw out.

And before our invention of killing tools and fire, humans scavenged for everything we ate, and many anthropologists would assert they lived happier and healthier lives than we do. (Mind you, there were not eight billion of them!)

Economic collapse (and the resultant chaos) will likely come much more quickly than ecological collapse, at least for most of us. Even then, it will not be an overnight occurrence. To modify the famous Hemingway expression, collapse will happen slowly, then suddenly all at once, and then it will slowly tail off until the system, and those dependent on it, disappear. Think of it like the right side of a ‘normal’ (bell) curve, or the descent of a roller coaster. For most of us in the west, we’re still in the first of these three phases of collapse.

So what do we do as we slide into the second, chaotic phase, as everything starts to fall apart and then does so “suddenly all at once”?

We cannot possibly know. It will unfold very differently in different places. The key word for coping with collapse into chaos is not sustainability or resilience or regeneration — once you’re on the way down, none of those is an option. Instead, the key word is adaptation. Some of the means by which we can position ourselves to better adapt are:

- acceptance: The sooner we are able to get past the ‘blame game’, and appreciate that things aren’t going back to the way they once were, the better off we’ll be.

- increasing our collective competence: We don’t all need to become individually expert at growing and harvesting our own food, but collectively, depending on who we define as our community, we will have to acquire and build on a whole suite of self-sufficiency competencies. They include the basic “know-how” of how to make/provide/manage our own food, clothing, shelter, water, energy, resources, tools, livelihood, infrastructure, health, education, art, recreation, and stories, and a host of ‘soft’ skills like conflict resolution, mentoring, persuasive and facilitation skills.

- learning from those experienced: In collapse, theoretical and conceptual skills will take a back seat to practical skills, so once it happens, we will need to identify those in our community who have hands-on experience doing essential things, and then learning by watching them and trying it ourselves.

- being pragmatic: We humans tend to be really attached to our models, ideas and ideals of how things “should” be done. We will likely have to settle for less ideal ways of doing things that work in the moment and in the situation we find ourselves in. Sometimes the perfect can be the enemy of the good, and of the “good enough for now”. Rigid commitment to some new ideal “how we’re going to live together” plan, especially if it isn’t “safe-to-fail”, could prove perilous. Increasingly, we’ll be looking for “adjacent possibilities” that will make things marginally better.

- drawing on the “wisdom of crowds”: As we face novel and unexpected situations, our personal specialized expertise is unlikely to serve us as well as a mechanism to draw upon the collective knowledge, ideas, and experiences of the whole community.

- collaborating: Few of us have experienced working in (often spontaneously) self-organized environments where there is no hierarchy, and where decisions are arrived at, and actions are taken, collectively by consensus and appropriate delegation. That kind of experience will soon be invaluable.

- exaptation: Exaptation is the accidental or deliberate repurposing of something from its original function to a new and useful function. The classic example is that birds evolved wings for warmth and cooling, and only later did these wings evolve for purposes of flight. Most scavenging and salvaging activities are inherently exaptive, repurposing activities. When we can’t get what we need “ready-made” we’ll have to cobble it together, exaptively.

- abductive thinking: Abductive thinking entails the capacity to see things from different trans-contextual perspectives, to listen empathetically and pay attention to outlying thoughts and perspectives and draw on them to imagine novel approaches and ideas, to draw on the “logic of hunches” and intuition, to rest in uncertainty and welcome and play with ambiguity, and to combine well-considered, pragmatic theory with direct experience. It requires lots of practice, good attention skills, and rigour. And a practiced capacity to hypothesize, and to test out hypotheses, and hold several hypotheses simultaneously. And a capacity for “small noticings” — recalling things you noticed in a different context that just might apply to the issue at hand. Few of us are very good at this.

- finding our community: While the community that we find ourselves in as collapse reaches the “suddenly all at once” stage, may be able to acquire and share the skills and resources needed to become a true community, it might well not. If not, we may have to keep searching until we find a community in which we usefully and comfortably ‘fit’. We are all likely to become ‘homeless migrants’ at least once in the coming decades, until we find it.

These skills and methods, the more we can acquire and practice them in the years to come, will help make us more competent at navigating collapse and chaos and co-establishing and building sustainable communities with just enough of the right constraints to be viable and healthy.

We cannot ‘prepare’ for collapse and chaos, because we have no idea how specifically it will play out where we live. But we can start, anytime, I think, acquiring the skills, knowledge, connections, networks and capacities, so that, regardless of how it happens, we’re able to adapt ourselves, and co-adapt with those we’re with, to cope as well as humanly possible.

“The key word for coping with collapse . . . is not sustainability or resilience or regeneration — once you’re on the way down, none of those is an option. Instead, the key word is adaptation.” Very well-stated!

Really excellent, Dave!

My only relatively minor rolling of my eyes and saying to myself, “Oh, Dave, you’ve got to be kidding!” is when you speak as if a good number of humans will still inhabit the planet “in decades”… as if a half-dozen already underway and rapidly accelerating (and, thus, utterly out of our control) thresholds have not already passed — virtually guaranteeing a 3-4C+ rise in temperature before 2050 that will likely extinct every single species we depend on.

Still, a truly excellent post… thank you!!

And I wholeheartedly agree with Tree.

Connie and I both found the statement she highlighted to be perfectly written!

Adaptation and co-adaptation are not only dependent on “skills, knowledge, connections, networks and capacities”, but also on location, location, location. All the adaptive skill in the world won’t do any good if there is no way to grow food, easily access water or sequester human wastes in one’s location. This means that, in a collapse, and despite high levels of adaptive skill, a modern city is not the place to be.

So, I suggest that one can prepare for collapse and chaos, first by relocating to a place that can sustainably provide the necessary food, water and shelter and then by developing maximal levels of interpersonal trust with those who are nearby (the latter being very personally rewarding in any case). The first pre-collapse preparation question everyone should ask themselves, “Can I trust my neighbors with my life”? The answer to this question may also be location dependent; how many people in a city high-rise even know their neighbors at all, much less well enough to answer “Yes”?

Agreed, Joe. That’s what I was getting at with my “finding our community” point. I appreciate the elaboration. It also means that, once airplane travel becomes a thing of the past, we had better make sure we find ourselves close to any family members and loved ones we want to live out our days with.