A brief review of Robert Sapolsky’s new book Determined, plus some other thoughts on the subject of free will.

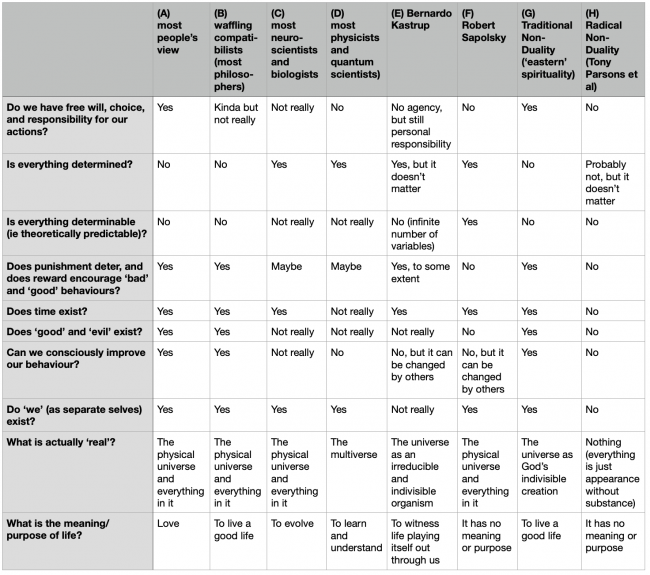

The free will “belief spectrum” (my own construction, and subject to revision)

In recent years, scientists and philosophers, often on opposite sides, have been weighing in more frequently on the subject of whether or not we have “free will”; that is, whether we have any control or agency over what ‘our’ bodies (including ‘our’ minds) apparently do, or responsibility for what they do (or fail to do), and whether we can act with intent. (This definition can be problematic, but whole books have been written just on that, so I won’t try to address that here.)

Philosophers (like members of all the social pseudosciences) can only espouse theories, which cannot be either proved nor disproved, so these theories are really nothing more than reasonably informed, well-considered opinions. Still interesting and sometimes useful, nevertheless.

Scientists can do marginally better, since a requirement of ‘good’ science is that its hypotheses must be based on some evidence, and must be falsifiable. So scientific theories are by nature always tentative and temporary, awaiting new theories that better fit the available evidence, or new evidence of their falsehood.

The distinction gets muddy, however, in the case of scientific hypotheses that cannot be either proved nor disproved “with current technology”, clever weasel words that allow “theoretical” scientists to falsely claim that their theories (like string theory) have a “scientific” basis, when they are substantially no more testable or scientific than the opinions of those in the pseudosciences.

In recent years, on the subject of free will, most philosophers have signed up as “compatibilists”, meaning that, using some rather excruciating intellectual and linguistic gymnastics, they would have us believe that, although reality is largely deterministic, there is still kinda some room for a little personal free will. (Philosophy has always been a tough gig, so you can’t blame them for waffling sometimes to avoid alienating their followers.)

For most of my life, I was a staunch believer in free will, and took delight in ridiculing the Skinner behaviouralists in the 1960s and 1970s when they were in vogue. So, in the above chart of attitudes about free will, I was in the “most people’s view” (column A) camp. Philosophically, I described myself as a phenomenologist — “I’ll believe it when I see it.” Both its absolutism and its romanticism (I still love David Abram’s book The Spell of the Sensuous) appealed to me.

It was another book, Melissa Holbrook Pierson’s The Secret History of Kindness that got me to reconsider the arguments of behaviouralism, including behaviouralists’ rejection of the idea of free will. The idea that everything we do is demonstrably (if not provably) a consequence of our biological and cultural conditioning, given the circumstances of the moment, struck me like a bolt of lightning. Melissa’s book helped me leap over the compatibilists’ incoherent waffling, and appreciate the arguments that some physicists and other “real” scientists were making about why there is actually no free will. I liked their arguments (summarized in column D) better than those of neuroscientists (column C), as the latter group’s credibility had been tarnished by early studies of ‘brain scans’ that proved to be seriously flawed.

So suddenly I found I had made a 180º turn in my worldview, from believing absolutely that we had free will, to believing absolutely that we do not. Suddenly it made sense to me that everything was determined (ie it followed from what came before) but not determinable or predictable (since the number of variables comprising what came before was effectively infinite). That was fully consistent with my study of complex systems and how they work.

Suddenly my instinctive (and conditioned) skepticism of the value of punishment and incarceration as a means of dealing with crime made sense (though incarceration may still make sense as a preventative measure). It was like a light went on: We are all doing our best, and no one is to “blame”.

And suddenly the idea that time wasn’t real, and was just a construct of the human brain, completely unnecessary both for a scientific explanation of the nature of reality, and for our successful functioning as living creatures, made sense.

These changes to my worldview also resonated strongly with the message of radical non-duality, whose speakers asserted clearly and consistently that there was no free will, and no such thing as time. They also made it clear to me how the message of radical non-duality is utterly different from the religious (eg some forms of Buddhism) and spiritual (eg Eckhart Tolle, Rupert Spira etc) ‘forms’ of non-duality (Column G), which assert that there is a followable ‘path’ to the ‘enlightened’ realization that everything is one (or ’emptiness’, or however ‘non-duality’ is defined).

So now I’m sitting in a kind of limbo. I’ve made the leap to no-free-will, totally conditioned, no one to blame, doing our best, and time as just a construct. But it’s another leap from there to the claim of radical non-duality that there is no me, that there is nothing ‘really’ real or ‘really’ happening (only ‘appearances’), and that there is no meaning or purpose to anything. I’ve tried to articulate these assertions on these pages since I first discovered them seven years ago. But since they only make intellectual and intuitive sense to me, rather than being ‘obvious’ or being supported by ‘evidence’, I’m not able to make the argument for them very convincingly. Perhaps no one can. Still, I can’t shake the sense that they’re correct.

So I’d kind of hoped that two new videos and one new book on the subject of free will might help me formulate and reconcile these positions better.

The first of these is a video that Bernardo Kastrup made recently, on the Essentia vlog. I really enjoyed this video, which covers an enormous amount of ground very succinctly, and is much more accessible, I think, than his written work. On the issue of free will, his impression is that it really doesn’t matter very much. He acknowledges that we as ‘individuals’ have no agency, but that’s because the whole concept of an individual is, to him, misleading. There is only the universe, a single massively-complex organism playing itself out the only way it can. We are just aspects of the universe and its playing-out. But just as behaviouralists say that our conditioning determines everything we do, yet our conditioning can have an impact on others and vice versa, Bernardo sees us and all our actions as ‘input variables’ that can affect other ‘input variables’ as the irreducible universe plays out. So those effects can change how the universe plays out. No agency, no ‘free will’ as most would define it, yet change can happen.

What I found most provocative in Bernardo’s explanation is that despite having no agency, he believes that in our internal “struggle” to make sense of the universe playing itself out, we have personal responsibility to express that struggle as effectively as we can, so that the ‘input variables’ that our struggle and our witnessing of the universe playing itself out, produce, will affect others in “responsible” ways and ‘positively’ affect how the universe plays itself out. We are like violins being played, he says, and our struggle is to be played for the benefit of the entire orchestra. And he says he has no difficulty, and very much enjoys, living in accordance with this worldview.

Then I read the new book by primatologist and neurobiologist Robert Sapolsky, Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will, which he discusses in this excellent interview by Nate Hagens. I’ve been following Robert’s work for years, and I found his uncompromising take on free will quite refreshing. Like Bernardo, he has little time or patience for compatibilist thinking. Unlike Bernardo, he does not believe we are in any way “responsible” for what we think or do. Like Bernardo, he thinks punishing criminals is wrong-headed. But unlike Bernardo, he doubts that the threat of punishment has a deterrent effect. Though, like Bernardo, he agrees that it still makes sense to limit the freedom of people we collectively believe are likely to continue to perpetrate serious harms against others — but as a preventative measure, not a punitive one.

And, like Bernardo, he believes we cannot “choose” to change or improve our behaviour, but that we are constantly conditioning each other, and hence changing each other, with unforeseeable consequences for ourselves and the world in which we live. As he puts it: “We don’t choose to change, but it is abundantly possible for us to be changed.” He cites the remarkable changes in our attitudes toward sufferers of epilepsy and schizophrenia (not to mention towards LGBT+ folks) as examples of how this unfolds, and asserts that we are in the process of similar positive changes in our collective attitudes towards sufferers of PTSD, and in our previous wrong-headed propensity to blame parents (eg of autistic children, by giving them vaccines) for the biological misfortunes of their descendants.

The book is exhaustive and exhausting. Like his last book, Behave, the latest tome is heavy on the biology that underlies our behaviour, and rigorous and exhaustive to a fault. But it’s designed to pass muster of critics from many disciplines, and you can safely skip some of the more technical sections without losing the thread. It’s entertaining, humble, and ferocious in its arguments, many of which are provocative and in the face of the thinking of the majority of philosophers and a large number of scientists, even in his areas of specialty. Absolutely worth a read if you care about the subject. Nate’s interview, linked above, will set the stage for your study of it.

His view of the human condition is refreshingly stark. He writes:

What the science in this book ultimately teaches is that there is no meaning. There’s no answer to “Why?” beyond “This happened because of what came just before, which happened because of what came just before that.” There is nothing but an empty, indifferent universe in which, occasionally, atoms come together temporarily to form things we each call Me.

But while Bernardo claims to be quite comfortable with this struggle to come to grips with a worldview that often doesn’t seem to make sense, Robert says that “99% of the time I can’t achieve this mindset, though there is nothing to do but try”. (Not that he has any choice, of course!) It takes a particular kind of confidence and courage to write a 500-page masterpiece on a subject, and then conclude that while he’s absolutely convinced of the truth of his belief, supported by mountains of scientific argument, he has to admit that almost all of the time he continues to act as if he (believes he) has free will.

…..

So I remain in the limbo between having accepted our complete lack of free will (Columns D, E and F of the chart above), and seeing as “obvious” that we have no real selves to even have free will (Column H). My ongoing discomfort stems in part from the realization that many of the arguments of both the for- and against-free-will camps, depend utterly on the acceptance of time and causality as being real. Throw out the stepping stones of linear time and causality, and the entire debate about free will gets either really murky, or completely moot.

Still, somehow, thanks in part to the contributions of these two gentlemen, the gap between no-free-will and no-one-to-have-it doesn’t seem nearly as great as it did. And, as limbos go, it’s not as uncomfortable as I would have imagined.

All this stuff is meaningless if you do not define what “exists” means.

So what’s your take?

Sapolsky is brilliantly re-stating what I accepted long ago as obvious and it’s true that we seem to be compelled to behave as if we do have free will.

A strange situation indeed. I don’t know why, knowing that free will doesn’t exist, we do have to continue living with such a charade. Maybe it just injects just enough dopamine rewards in our brains for us to continue with our meaningless existence.

For all we know we “live” (is that more than dissipating available energy gradients?) in a pointless universe that seems to be hellbent on reaching a kind of nirvana state where nothing can happen anymore. In the process of going nowhere as fast as it can it allows some structures (such as conscious hominids wondering about free will), to temporarily thrive on free energy sequestered from the environment. That ‘s all, at least so it seems.

I wrote a note to Robert asking him to consider revisiting Julian Jaynes work on the bicameral brain and the hypothesis that the entanglement of the two halves of our brain (https://howtosavetheworld.ca/2020/10/27/the-entanglement-hypothesis/), uniquely in the human species, was a kind of evolutionary experiment gone terribly wrong, and ultimately led to the illusion of the separate self and of free will, and everything that emerged out of that including language and civilization.

He’s the only person I know who could credibly explore that. If it’s true, and I find it a compelling hypothesis, all our suffering and sorrow is a tragic consequence of a spandrel, a Frankensteinian evolutionary misstep. With the inevitable ending we are now witnessing.

@Dave

You seem a bit short in your investigations, do you know that there are more than 5 000 000 scientific & philosophic publications about consciousness?

Dave, don’t expect too much from Sapolsky re-analyzing Jaynes bicameral hypothesis.

Using terms like bicameral, entanglement, a.o. iro of complex and complicated structures, such as human brains, is not very helpful. Since Jaynes’ hypothesis formulation an enormous amount of brain and neurological research and modeling has been done and we still don’t remotely understand things like consciousness and why it came to exist in certain structures.

I don’t know why we have to be so curious about everything and why we have to figure out how the universe works or how things fit together to produce certain outcomes.

It is unlikely that, as evolutionary structures that are in it for a compulsory ride, we have the necessary biological equipment and means to penetrate to the deeper levels (at least if it’s not onion peels are the way down) of understanding in this crazy universe.

But for some strange reason we have no option but to keep trying to figure things out.

Maybe there is some evolutionary benefit involved, maybe it’s just a stupid side effect. Who knows? And yes, I think we’ll keep playing this knowledge acquisition game as long as there is sufficient food to power our silly, unfortunate (from our perspective) brains.

@Ray

For an interesting view and lots of recent references I would recommend:

Consciousness: Matter or EMF? Johnjoe McFadden

About “evolutionary benefits” see:

“The Interface Theory of Perception” Donald D. Hoffman

Thanks for sharing the links for Bernardo. And interesting for me that you find him worth considering, since you seem opposed to anything having any meaning.

And now for something completely different, a non-dualistic awakening (in French, sorry).

No free will, no problem…

An addendum.

Since the vast majority of people have idiotic opinions if they truly acted out of their own will the world would be even worse. :-)