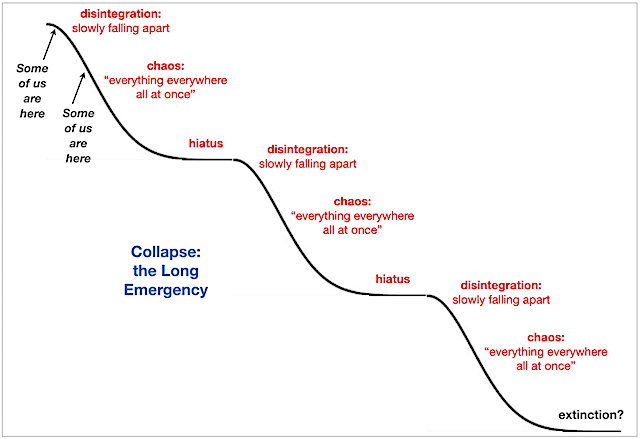

my own diagram of what Jim Kunstler calls “The Long Emergency” — a gradual multi-stage collapse over an extended period

My new adopted community of Coquitlam is an exceptionally ethnically and culturally diverse one. It also has a much larger proportion of kids in their teens and twenties than most of Greater Vancouver’s neighbourhoods. As a result, many (probably the majority) of the young people I meet and see here are what have been dubbed “Third Culture Kids” (TCKs).

Essentially a TCK is a person who was born into one culture but grew up immersed in a very different one. Most TCKs are first-generation immigrants to their adopted country, though some were born in their adopted country shortly after their parents immigrated here. What they all have in common is the challenge of having to manage with, and make sense of, two very different cultures. In some cases, they say that has resulted in them essentially creating a “third culture” that works with and bridges the culture of their parents (and their early childhood) and the culture of their adopted country.

Navigating the world successfully as a TCK, it seems to me, requires acquiring some exceptional skills, knowledge, and practices that most of us never have to worry about. This got me thinking about whether or not the singular capacities and competencies of TCKs might be especially useful to all of us as we face the accelerating collapse of our economic, political, social and ecological systems, and the civilization that depends on these systems.

My thoughts about this are based on a kind of theory of human nature that ‘explains’ collapse and our current predicament and our struggles dealing with it. This theory (subject to change) goes something like this:

- We humans thrived for much of our first million years in our tropical rainforest homes in trees. Just as during the previous 4 billion years of evolution, this was often a tumultuous period of mass extinctions, and most of the species that ever lived have disappeared. We have come close a number of times.

- At some point in our species’ middle evolution, some massive cosmic radiation bombardment and/or a previous enormous climate change (or some other cause we have yet to discover) destroyed our natural rainforest habitats, so the humans of the time found themselves ‘cast out’, in search of a new place to live.

- Over time, in our new, foreign, less hospitable savanna and coastal biomes, we evolved new mental capacities to deal with these new environments; otherwise we’d have gone extinct. One of those new capacities, enabled perhaps by the ‘entanglement’ of our brain circuitry, allowed us to imagine things and then make them real, something no other creature could do.

- That gave us the ability to develop abstract language, weaponry, agriculture, civilization, and other technologies. But a side effect of that entanglement was a terrible feeling of separateness and vulnerability to harm from ‘others’, that has made us, I would argue, all mentally ill. Instead of simply ‘being’ part of a larger whole (Gaia — the single ‘organism’ of all-life-on-Earth), we suddenly perceived ourselves to have separate ‘selves’ apart from everyone and everything else, and in control of and responsible for the survival of the bodies that ‘housed’ those selves.

- The resultant sense of vulnerability and helplessness must have been terrifying to humans with these newly-entangled brains. Suddenly instead of our behaviours being dominated by simple instinct, we became confused and conflicted about what we ‘should’ do, convinced we had free will and choice, and that actions harmful to our vulnerable selves could be attributed to sinful or evil or deranged intent of other selves. Hence we became driven largely by fear and hatred, and traumatized, trying to control what in fact is not in ‘our’ control at all. Our actions became disconnected from the rest of life on Earth, and often competitive, destructive, and dysfunctional for the planet as a whole. In this deranged disconnection, we massively overpopulated the planet, and created ‘civilizations’ chronically exhausted from overwork and rife with unprecedented scarcity, violence, precarity and stress. This has created a vicious and self-reinforcing cycle of (i) chronic stress and scarcity, (ii) trauma, (iii) violence and war, and (i) conditioned fear and hatred, that has lasted at least 10,000 years.

- The consequence of this vicious cycle has been the inadvertent destruction of our planet’s carrying capacity, to the point that our ecology, the economy, and the social and political structures that depend on them have been disturbed and desolated so profoundly that these systems are now in the accelerating stages of collapse. Everything is falling apart. I think we all sense that, even those of us who are in denial.

So that’s where I believe we are now. All perhaps attributable to dramatic changes in our species’ native habitat, and a consequent unfortunate evolutionary misstep.

All animals are, I would argue, conditioned by their biology and their culture to do what they do. Most of us humans have historically lived in highly homogeneous communities with little exposure to, or mixing with, other cultures (often even when many different cultures coexist in the same geographic spaces). That cultural homogeneity has, in past, made things simple for us (little diversity of opinion or ideas to have to process), and also made us somewhat xenophobic (we fear what we don’t know).

But more recently, our technologies are enabling us to become more ‘international‘. We travel ‘abroad’ more (except most Americans, it seems). We’re exposed to more, and more diverse, cultures. We’re trying, most of us, I think, to appreciate, integrate, and adapt to different cultures and a greater diversity of ways of thinking and being in the world.

TCKs are, I think, on the leading edge of that shift — by necessity, because they live it every moment of their lives.

So what does that mean for their capacity to cope with collapse? Are they so buffeted by the complexity and frictions in the world that they are more traumatized than the rest of us, unable to find a safe ‘home’, unable to ‘attach’, and so confounded by diversity that they cannot discover who their authentic selves are? Or does their exposure to diverse cultures actually give them more tools, methods and better capacity and competency for coping with collapse (and other forms of abrupt and radical change) than the rest of us?

Or to put it in starker terms — If TCKs are a part of the possibly two billion ‘collapse refugees’ we may well see in the coming decades, will they be able to show the rest of us the way?

My hope would be that their challenging experiences enable them to see the world with a kind of ‘binocular vision’. And I would hope that that vision might give them an advantage — the ability to perceive complex situations in a more complete and nuanced way than we ‘monocultural’ humans can, and to be more comfortable dealing with them, and with constant, never-ending change.

Part of my interest in this is our propensity to use propaganda, mis- and disinformation and censorship to disrupt this ‘binocular’ perception — the goal of these tools is, after all, to simplify and reduce the cognitive dissonance of today’s messy information and cultural landscape, to get us back to the ‘safe’ good old days when everyone in a community knew and believed more or less the same things. Can TCKs see past this ‘dumbing down’ deception? Or are they so overwhelmed that they might actually welcome it, despite its cost (of having to reject part of their worldview in order to ‘fit in’ and belong in their new adopted culture)? My sense is that it’s the former. They have, in my experience, excellent bullshit radar.

So I’ve been trying, politely, to talk about all this with TCKs that I know and meet.

You won’t be surprised to learn that my tentative answer to this question of TCKs’ competence and capacity to deal with change is “it’s complicated”. Cultural agility and adaptability vary enormously from person to person, based on a host of factors, beyond the cultural diversity they’ve been exposed to and had to adapt to.

As for all kids, it seems having parents with good relationship and communication skills makes a huge difference in their kids’ ability to cope with the changes they face. But while I’ve only spoken to a handful of TCKs, the ones I’ve spoken to mostly didn’t find their parents, and what their parents had taught and imbued in them, to be particularly helpful. In other words, their parents were a lot like modern parents everywhere — doing their best, but really struggling to find time and capacity to compass their kids when their own lives were already so hectic and bewildering. What Gabor Maté describes as the lack of essential secure attachment in early childhood (despite parents’ best efforts to provide it), seems to be just as much a problem for TCKs as other kids.

What did help TCKs, not surprisingly, was finding strong supportive relationships in their new community. I would have expected that doing that would require having some strong ‘social graces’ and an extroverted personality. But to my surprise, most of the TCKs I spoke to described themselves as introverted. Just as “community is born of necessity”, it would seem, so is the capacity to make new friends and social ‘circles’. If you have to do it to remain sane, you learn to do it.

Several of them described what might be called a kind of nostalgia for their birth country — when we’re young, we tend to see more of the good things and overlook the problems. And they especially missed the friends they’d left behind when they immigrated. New technologies enable some relationships to continue “long distance”, but, as one TCK told me, “It’s just not the same”.

When I interviewed some TCKs, I had been reading about the struggles of many new immigrants who were essentially sold a bill of goods when they came here. In particular many found that their professional credentials from their home country were simply not honoured here (that’s the largest source of unhappiness of new immigrants, according to several cultural organizations for ‘new Canadians’). That of course made life much more difficult for them, and for their TCKs. Many have actually given up, and returned to their home country or sought out another new country to live in.

I also learned about the outrage of some private “international colleges”, which charge foreign students exorbitant tuitions and then deliver substandard courses and programs that no employer would ever consider as constituting a real post-secondary education. These fraudsters are largely unregulated, and they are giving Canada (and probably other western nations) a horrible reputation for this abuse. No surprise that many TCKs who come here for university training end up returning home disappointed, and sometimes full of disgust, guilt and/or shame.

I think we’ve at least finally learned enough about the challenges of adapting to a new country and culture, that we’re no longer espousing the 250-year-old ‘melting pot‘ myth — the claim that we must enable new immigrants to be ‘assimilated’ as quickly as possible, and get them to largely forget the culture of their birth. It’s an unhealthy, arrogant ‘solution’ born of Empire mentality and evangelical Christian fanaticism, and it’s never worked. The horrific damage it’s done to indigenous populations everywhere might never be healed.

Here’s what ChatGPT had to say about the biggest challenges for TCKs, verbatim:

Third Culture Kids (TCKs) are individuals who have spent a significant part of their developmental years in a culture different from their parents’ culture and the culture of their passport country. This unique upbringing can present both advantages and challenges. Some of the biggest challenges for Third Culture Kids include:

-

- Identity Formation: TCKs often struggle with forming a stable and cohesive sense of identity. They may feel like they don’t completely belong to any single culture, leading to questions about who they are and where they fit in.

- Cultural Rootlessness: TCKs may lack a deep connection to any specific culture, as they have experienced multiple cultures during their formative years. This can lead to a feeling of rootlessness or a sense of not having a true home.

- Relationship Building: Building long-term relationships can be challenging for TCKs, as they may be accustomed to saying goodbye and adapting to new environments. This transience can affect their ability to form deep and lasting connections.

- Reentry Challenges: Returning to their passport country or settling in a new culture can be difficult for TCKs. They may experience reverse culture shock or struggle to adjust to a lifestyle that is different from what they have known.

- Educational Transitions: TCKs often move between educational systems, which can create challenges in terms of academic continuity and adapting to different teaching styles. They may also face issues related to the recognition of their qualifications.

- Language Dynamics: TCKs may be multilingual or have proficiency in different languages, but they may also face challenges in fully mastering any one language. This can affect communication and academic performance.

- Dual Loyalties: TCKs may feel torn between loyalty to their passport country and the cultures they have lived in. This can create internal conflicts when it comes to national identity and values.

- Emotional Resilience: Constantly adapting to new environments can require a high level of emotional resilience. TCKs may become adept at navigating change but may also face emotional exhaustion and a reluctance to form deep emotional attachments.

It’s important to note that while TCKs face unique challenges, they also often develop strengths such as adaptability, cross-cultural communication skills, and a global perspective, which can be valuable assets in various aspects of their lives.

Sounds about right. Dealing with unexpected illnesses and unfamiliar weather and climate might be added to the list.

What surprises me is that none of the TCKs I spoke with (most of whom are no longer ‘kids’) were daunted by these challenges, though some found them overwhelming at times. In fact I’d say without exception they are more thoughtful, more well-balanced, and mostly also happier than most of their non-TCK peers. Amazing what you can do if you have no choice.

As someone with an aversion to labels, I was quite pleased that the TCKs I spoke with don’t really ‘identify’ themselves with any particular nationality, either the one of their birth or the one they now call home, nor some hyphenated concatenation of the two.

Several mentioned that it took them a long time to actually ‘find their place’ in the new culture they found themselves in, and they found that frustrating. “I thought it would be easier”, one young woman told me, not blaming anyone or anything for that situation.

A couple of them told me, a bit shyly in one case, that they didn’t find the people of their adopted country (Canada or the US) to be terribly informed about history, geography, or world events; nor did they find them (us) to “read much” or be as curious about things as they had been brought up to be. From my life-long meetings with non-North Americans I can totally relate to that.

And I can likewise relate to the comment that we in North America have a lot to learn from other cultures about hospitality — not that we’re rude, we’re just kinda awkward about it, and we’re unfamiliar with simple rites (such as how to make an engaging invitation, and how to offer appropriate gifts to your host or guests) that make visits wonderfully pleasant.

This was not at all a scientific or representative survey or study of TCKs, and I’m always wary of generalizations. But I thought what they told me was interesting, and kind of reassuring.

My conversations got me thinking about the challenge of language — not only having to learn a new and unfamiliar one quickly, but the fact that, arguably our language determines and changes how we think and who we are. Learning a new language is more than translating; it’s understanding the entire way of thinking and of being that underlies the vocabulary, syntax, and nuance of different languages. And much (perhaps most) communication of meaning (thought and feeling) is communicated not by the words used but by the tone of voice, eye, face, and body ‘language’ that accompanies saying it. And the ‘rules’ for how that non-verbal communication is (and is not) done in each culture are as varied as the languages themselves.

If you’re a TCK, you not only have to learn the words, but also what gestures, voice tone, and type of eye contact are appropriate in the context of what you are saying. This is dizzyingly complex.

And as you learn a new language, it even changes the way you think. When I finally learned French, I was surprised to discover that I expressed myself (words and body language) much differently when I spoke in French compared to English, and found that some of the things I was trying to convey in French just didn’t make sense in that language, so my beliefs and ideas shifted. I learned the power and significance of a Gallic shrug, for one thing!

So much for the challenges, and advantages, of being a TCK. What does this mean for the ability of these extraordinary individuals to cope with the accelerating collapse of our economic, political, social and ecological systems?

To address that, I have to take a step back and reiterate how I think collapse is currently unfolding, and how I think it will unfold as it accelerates in the coming years and decades. The most important thing to keep in mind, I think, is that collapse is going to be slow and punctuated. Those who’ve studied history and systems theory remind us that collapse does not occur like in the Hollywood movies with Mad Max and the Zombie Apocalypse occurring and then being vanquished by the brave conquering hero, all in the space of two hours.

Instead, collapse is likely to occur in waves and over decades, like the multiple S curve pictured in the image at the top of this post. Heroics, panacea technologies, and dramatic cultural transformations are unlikely to occur or even be particularly useful. Our current accumulated knowledge and know-how is not going to be that important.

Instead, what will be most important is our capacity and competence to learn new things, and the collective capacity and competency of our adopted communities.

This is where the experiences and challenges faced by TCKs will, I think, give them an important advantage, and make them natural mentors for the rest of us as we cope — slowly, over decades — with radical change to our ways of living, thinking and being. They’ve had practice making dramatic cultural shifts, accommodating different ways of thinking, different beliefs and priorities, and different ways of doing things. Dealing with the sheer bewilderment of it all.

As economic, political, social and/or ecological collapse forces billions of us to migrate to new and unfamiliar environments (perhaps just as our pre-entangled-brain ancestors did hundreds of millennia ago), the capacity and competency to learn, and the collective capacities and competencies of our adopted new communities, will, I think, determine whether we will thrive or go extinct. How, for example, will we manage when imported goods, the private automobile, the shopping mall, and the corporate employer all vanish from the physical and economic landscape?

The ones we will have to look to are those who — because they were forced to — have already begun to acquire and practice these capacities and competencies. That includes not only TCKs, but also the many castes of our society that have long been abandoned and passed over in our horrifically unequal and unfair modern societies — what has been called the precariat or pretariat, who Aurélien has defined as the “ordinary people, mostly reasonably good, mostly reasonably honourable, trying to do their best in a world where power lies elsewhere”.

That will include people who have learned to make community in our broken inner cities and (in Europe) neglected, immigrant-filled suburbs. And in slums, in areas often not even recognized as legitimate parts of exploding cities, the world over. And of course, in the streets, unhoused. We have a lot to learn from those who are already dealing with full-on collapse, and have been doing so for a long time.

There is something satisfying about what this will mean for the utter redistribution of power that is inevitable as collapse intensifies. As Bob Dylan put it in his hopeful anthem The Times They Are a-Changin’:

Your old road is rapidly agin’;

Please get out of the new one if you can’t lend your hand

For the times they are a-changin’.

The line it is drawn; the curse it is cast. The slow one now will later be fast,

As the present now will later be past — The order is rapidly fadin’,

And the first one now will later be last, for the times they are a-changin’.

There are those who think they can cope with collapse by hiring a private army and hoarding wealth and barricading themselves inside their mansions. There are those who think there is only one ‘correct’ path to living a good life, and that their faith will be rewarded by the gods, as ‘sinners’ perish in collapse. There are those who think that education and being born into the right caste provide a guarantee of material success and security, and the right to be ‘leaders’ of any world order, even when everything they have ‘led’ us to so far is falling apart.

They are all in for a big surprise.

I think we will soon (in a few decades at the latest) find ourselves in a world where the communities that are thriving will be those whose members have been willing and able to set aside everything they believed and thought they knew, and set aside their sense of authority and what is ‘right’ and ‘wise’, and embrace uncertainty, and change, and the fact that there are no ‘one right’ answers, and learn everything that’s really important completely anew. The old rules, values, ‘knowledge’, privileges, faiths, myths, and hierarchies will simply no longer apply.

And I think that many in the vanguard of thriving post-collapse communities might well be Third Culture Kids, who are already learning, the hard way, what we will soon all have to learn to cope with collapse. Scary, uncomfortable, unpredictable, immensely difficult, frequently horrifying, and yet totally awesome. At my age, I’m afraid, I’m unlikely to see most of it unfold. But damn, I wish I could be there to witness, to play my part, and to cheer them on.

Thanks to my friend Siyavash Abdolrahimi for inspiring this article and for his help in thinking this article through. Any errors or misrepresentations are inadvertent and strictly mine.

I think that collapse will overwhelm just about everyone, even Third Culture Kids. Your chart of the “long emergency” may be generally correct (I think the steps down will be steeper and deeper), but most collapse commentators, including you, seem to gloss over the fact that the graph is also one of population decline in addition to economic and technological decline.

Circumstances in which the majority of people now alive are destined for a miserable, premature death will rend the social fabric. It’s easy to imagine what that rending will mean and this is why “hiring a private army and hoarding wealth and barricading themselves inside their mansions” makes sense to some people. Darfur, Tigray, Somalia, Syria and many other places provide clear examples of the kind of things that will happen during collapse. I don’t know what kind of skills are most appropriate to dealing with famine, banditry and warlordism, but I don’t see Third Culture Kids having any particular advantage.

So, I do think some small fraction of the people now alive will survive collapse and anyone with a minimal amout of prudence is girding themselves for the attempt. I can accept most of your adjectives for describing collapse, but “totally awesome” is one I will never use.

Some 4 years ago I suggested that experience of straddling worlds (both of nation and discipline) made one more creative . see https://nomadron.blogspot.com/2020/03/does-being-outsider-improve-quality-of.html

Dave,

I am not in the business of accommodating collapse. I am in the business of avoiding collapse. Would you like to have a conversation with me. I will help you write such an article.

JackAlpert@me.com http://Www.skil.org

Daoudjan, thanks for posting this.

Perhaps, some TCK’s have a little bit of a leg up over non-TCK’s in relational capacity, but I’m with Joe that collapse will overwhelm everyone. As a quasi-TCK, I find I am just civilization-addicted as the next person. I have to wonder for how much longer we will be able to repeat the frictionless operation of ordering goods with just a few clicks?

Still, I think it is worthwhile to devote a whole post to TCK’s. I’d never heard of the term (and thus didn’t have the frame for my experience) until some 15 years ago. And after that, it clarified a *lot* for me, how even though I was born in the US and have lived here most my life, I feel like a foreigner here; how I feel like I belong and don’t belong at the same time, etc.

This is something of a different aha – a blinding flash of the obvious- that I had the other day– that a huge part of preparing for collapse is preparing to die! If we have completed the (mostly inner) work before dying, perhaps the rest of the adapting we would need to do during collapse would take care of itself??

What Joe says is also largely the way I would put it.

What young people today have the skills to find enough food on a constant basis to survive the coming fast/slow collapse . Nothing special about TCK’ s. They will be as clueless and powerless as everybody else.

Survival, in times of 8 billion people scurrying around and fighting for a few scraps of food, is no child’s game.

Maybe the psychopaths with their finger on the atomic trigger will help them out so that they must no longer bother with scurrying around.