New Yorker cartoon by Peter Steiner

New Yorker cartoon by Peter Steiner

Lyz Lenz cites Rebecca Solnit as having told her “Every story men love to tell is Pygmalion.” A trace hyperbolic, perhaps, but Lyz goes on to list some of the many novels and films that are essentially about men creating “the perfect woman”. And how everything goes askew after that.

I found this interesting because it runs counter to, or perhaps parallel to, the oft-stated belief that women select a male partner for his potential, what he might become (with her guidance), rather than who he already is. And then, when she has presumably maneuvered him into proposing a relationship with her (so it appears to be his decision and initiative), she gets to work to help him to realize that potential.

It might seem, then, that the difference between male and female idealism, when it comes to partnering, is that the male wants to build his perfect mate from scratch, while the female, perhaps more pragmatically, is prepared to work with what is already there. At least, that is the ideal once they each realize that the perfect partner, “ready made”, was just a dream.

These are of course stereotypes, but they raise a number of, I think, interesting questions:

- What accounts for these different ideals, the qualities sought in a mate?

- What are the implications of these differences in terms of the possibilities of having joyful, functional relationships, and what can one do, if anything, given those implications, to give one’s relationships the greatest chance of bringing happiness to both partners?

- Are the dynamics different in what we look for in an ideal friend, from what we look for in an ideal partner, and if so, how and why?

Books could be written on any of these subjects (and have been), but I wanted to look at these questions through the lens through which I have of late come to see the world: (1) That we are all doing our best, (2) that we have no free will and hence our behaviour is strictly the result of our biological and cultural conditioning, (3) that our species is currently suffering from massive, ubiquitous and debilitating trauma, and (4) that our current global civilization is in an accelerating state of inevitable collapse.

The components of this lens are, of course, highly debatable (and I have discussed my reasons for believing them previously, and often, on this blog). And these components are also interrelated, in complex ways. But for this essay, I’m going to take this sad state of affairs as a given, and try to explore how it might have contributed to the current unhappy state of many human relationships, and vice versa, and what that might mean for the fabric of our society as we try to cope with everything falling apart.

The obvious place to start this enquiry is with love — how it compels us, how it’s different for men vs women, what our expectations of it are, and how those expectations evolve (and generally lessen) over the life of a relationship.

It seems we have no choice about who we fall in love with (it’s our biological and cultural conditioning again). But somehow there seems to be some wiggle room to alert us to relationships where intuitively we sense it’s a bad idea, which can prevent us from falling in love when we otherwise probably would have. There’s also a lot of evidence that even when one or both partners knows a relationship is no longer what it once was, inertia tends to keep the couple together until something (often an affair) precipitates a formal separation.

I wrote about the dynamics of monogamous relationships 13 years ago in an article that argued that our civilization, and in particular its capitalist elements, conspire to control us (keep us all aligned, doing the same things, obedient, anxious, and placid) by creating a world of artificial scarcity, including a scarcity of love and compassion, that makes us fearful of being alone, even when the alternative is an unsatisfying or even abusive relationship.

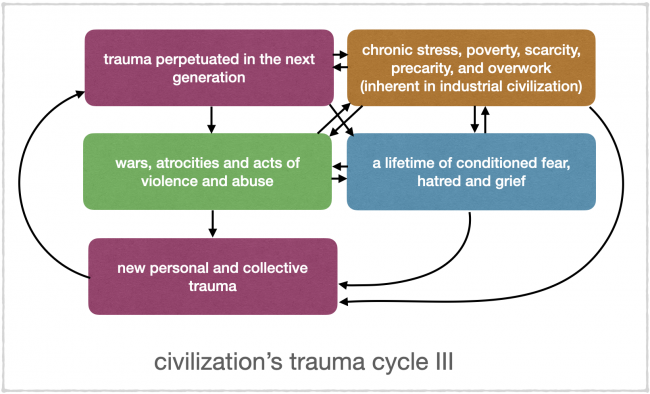

This artificial scarcity is, I think, an essential component of the trauma cycle that is both a driver and a consequence of our wasteful overconsumption, overpopulation, and our insatiable desire for far more than we actually need:

In the 2011 article I also reviewed how our current ideal of lifelong monogamous partnership evolved, citing Laura Kipnis’ book Against Love:

The book argues that monogamy is unnatural and unhealthy, and possibly complicit in our emotional detachment from political life and our ecosystem as well. Laura sees monogamy as part of the cultural indoctrination that leads to wage slavery and mindless consumerism — it’s all about creating scarcity (in this case, scarcity of love and sex) to drive up the ‘value’ of both, and hence needlessly drive up the hunger, desperation and jealousy (and, alas, resultant domestic violence) of so many in their anguished search for them. And ultimately, it’s all about creating a ‘consumer’ populace that is (financially and emotionally) endlessly needy, unsatisfied, and wanting more.

When I wrote this, I blamed capitalist greed for this scarcity. I’ve become a bit more charitable since then, and I’d now say that scarcity was maintained to keep 8B apes, not evolutionarily meant to be obedient members of a vast amorphous and uncomfortable consumer culture, in line. We have, in short, been culturally conditioned to be needy, anxious, dissatisfied, uncertain, off-kilter, fearful, passive, dependent, and obedient, because otherwise we’d likely have killed most of each other off by now. (Primatologists assert that no other ape could ever be conditioned to put up with the restrictions we have come to accept as normal.)

When it comes to relationships, that neediness, dissatisfaction, fearfulness and dependence plays out in a (justifiably) perceived scarcity of romantic and sexual partners, with all the anxieties, jealousies, and envy that that entails. So what is our answer for dealing and coping with this? Perhaps the male answer is to build more “from scratch”, Pygmalion-style, while the female answer is to settle for less, and work harder to bring one, or a few, of the sad pool of male partner candidates “up to scratch”.

So we have male fantasies about robotic females and reprogrammed “bimbos” to cater to the man’s every wish (mostly: sexual availability, fidelity, and willingness to do most of the labour, both physical and emotional, in the relationship). And we have female fantasies about attentive, appreciative, competent, supportive, faithful, dependable, hard-working males who do their fair share of the domestic work, look relatively attractive and do occasionally adorable, unexpected things*.

The male ideal is actually less heartless and outrageous than it might at first appear. (But then, I’m a male, so I’m biased.) If there’s a perceived shortage of something, the conditioned male instinct, it would seem, is to build more of them. Hence the Pygmalion tendencies. If there were lots of very lifelike, utterly obedient female robots with very sophisticated programming, would men be satisfied, to the point of not wanting relationships with human females as much? I think it’s doubtful. If there were an abundance of androids and a scarcity of human females, men would probably continue to fret (and fight) over what was scarce. And (a great surprise to me), men actually want children more than women do. And based on surveys of male sexuality I’ve seen, I suspect that the novelty of high-tech non-human sex would wear off quickly — perhaps even faster than it would for women.

So I would argue that what men think/fantasize they would ideally like in a relationship with a woman, and what would actually make them happy, are two very different things.

I would hypothesize that this is in part because most men just aren’t particularly emotionally aware of what they really want. That is probably also due largely to differences in conditioning, but it doesn’t bode well for enduring relationships.

Do women know better what they really want from relationships with men? As with men, my guess is that most women think they know what they want (see list* of qualities above). Getting those things would likely go a long way to making them happy/happier in their relationships. There is, after all, an enormous inequity between what men and women, on average, put into a relationship, and what they get out of it.

But my sense is that that ain’t going to happen (things are the way they are for a reason, and IMO that’s all about our conditioning and not something that awareness of its “injustice” is going to change). The root cause of this inequity, and the unhappiness it produces, I think, is systemic, and goes back to the evolved social fabric of our civilization.

I think we have to go deeper than inherent male laziness (a laziness which I’m nevertheless quite willing to acknowledge) leading to what the above-linked song calls men’s “false incompetence” (as in: “When I do the [enter type of tedious work here] I can never do it as well as you do, dear”).

To do that, I think we have to go back to the very structure of our civilization culture. And that structure is atomized, with the tasks and responsibilities once jointly held by the community having been transferred to the nuclear family. Most of the drudgery of day-to-day life (the tasks of child-rearing, gathering and preparing foods, and ‘maintaining the nest’) was once done by the community collectively, ensuring that the workload was more evenly spread and had less duplicative work and lower resource needs per person than the ‘single family’ home requires.

Even in avian communities, where birds supposedly ‘mate for life’ (though they actually don’t), the whole community drops everything and assists in the work of feeding and caring for the young. In crow families, for example, the young stay with their parents for their second year of life and help with all aspects of child-rearing of their younger siblings. And un-partnered crows pitch in as well. Geese even have community baby-sitters.

cartoon by Will McPhail, from his website

But Kelly (who knows her feminist history) reminded me that even in many pre-civilization cultures where the community was actively involved in collective work, there were still apparently substantial inequalities, most of them reflected in the heavier burden on women in maintaining both the social fabric of the community and in maintaining and navigating personal and societal relationships (the aforementioned ’emotional labour’). When I asked her why she thought this inequality had arisen, she identified a possible more fundamental culprit: the concept of personal property.

Go back far enough in human history, back to when humans belonged to the land, rather than the other way around, and we are more likely to find something closer to true equality between men and women. Because as soon as we envisioned personal property — the ‘ownership’ of land, buildings, animals — we could envision one person or group owning another person or group — slavery. It was the ‘invention’ of slavery that enabled the idea of someone being the property of someone else, and hence made hierarchy and gender inequality possible and even politically ‘acceptable’.

But even if you look at the most apparently misogynistic wild primates — namely baboons and gorillas — you have to consider Robert Sapolski’s long-term study showing how one brutal patriarchal baboon tribe suddenly and completely transitioned to an enduring peaceful matriarchy when the circumstances allowed it (it happened when all the alpha males suddenly died of accidental poisoning). This study conclusively demonstrated that patriarchal primate behaviour is not inherent or biologically-driven. It is all cultural conditioning.

So — a recap before I return to the three questions posed at the outset of this essay:

- The artificial creation of material and relational scarcities, which evolved as part of civilization (and especially capitalist) culture, is likely behind a lot of the social and emotional dysfunction we are living with today.

- Thanks to this (probably accidental, unintentional) civilizational dysfunction, we have been culturally conditioned to be needy, anxious, dissatisfied, uncertain, off-kilter, fearful, passive, dependent, and obedient.

- Because of the disconnection and trauma that this conditioning has produced in us, we often no longer know what we really want in our relationships, and when we think we know, and pursue that, we often find it wasn’t what we really wanted at all.

- What we perhaps actually want are the kinds of interpersonal and communal relationships that were likely commonplace prior to our civilizations’ atomization of community and its invention of personal property.

There seems to be something at the very root of the human animal (and perhaps every animal) that aspires to be wild and free. And we know instinctively we are not, so we are unhappy, dissatisfied, longing for something but not knowing quite what it is. We are, I would assert, caged, constrained, by the cultural conditioning that will not let us be our authentic, wild, free selves. And our culture, with its artificially-created but massive scarcities, also renders us terrifyingly insecure. So we seek to be wild and free, but at the same time we seek to be safe and secure. That shouldn’t be too much to ask for, should it?

Most men, more than most women I think, seem to think that possessions (including the possession of wives and children, power, fame and wealth) will somehow fulfill that longing, fill that empty space. Most women, perhaps more pragmatically due to their cultural (and to some extent biological) conditioning, look to make the best of the situation they’ve been handed. Possession of things to many women is, it seems to me, often just a means to an end, and that end is frequently security. Thanks to millennia of cultural oppression, security is, for most women, I think, the ultimate and never-ending scarcity. Though a little wildness, a little freedom, a little joy for women would be nice, too! At least the freedom to not be treated as a possession, as ‘property’!

So that leads me to my tentative, and incomplete, answers to the three questions:

- Most men look ideally for a partner who will both allow them to be wild and free, their authentic animal selves, and also do most of the work to provide the essentials of a secure space for them to live and raise children. Most women, I think, look pragmatically for a partner who will help provide them a safe and secure place to live and perhaps raise a family, but also, ideally, give them the space and opportunity to be their authentic, wild and free selves as well. That’s a generalization, of course, and I think the lines between the two genders’ ideals are rapidly blurring. And I believe our conditioned fears, long-standing hatreds and unresolved anger, grief, and trauma also play heavily into what each of us seeks and wants in a partner.

- What this means, I would guess, is that what most males and most females are looking for in a romantic relationship aren’t substantively that different. Our priorities may differ depending on our gender and (even more) on our personal circumstances. And because our behaviour is conditioned, we’re more likely to be able to keep our relationship functional if we can at least appreciate why those priorities, ideals, and desires are often so different. Some of the happiest couples I know are those who live next door to each other rather than in the same home, and have separate bank accounts. And they seem both exceptionally self-aware and exceptionally aware of (and accepting of) each other’s conditioning, triggers and traumas.

- How are the dynamics, priorities, ideals and conditioning between friends different from those between romantic partners? Not that much, I suspect. Our expectations of friends are generally different from (and often lower than) our expectations of a romantic partner, but the same dynamics, priorities, ideals and conditioning are often in play. Perhaps not surprisingly, I would guess that most female friendships are deeper and more intense than male friendships. As for platonic male-female friendships, that would require a whole separate article.

Lyz’s article, mentioned at the top of this post, which got me thinking about all this, supports the thesis of her new book This American Ex-Wife — that many married women would be much happier and much better off in every respect getting divorced and living alone, including raising their children. She is particularly (and IMO justifiably) incensed at the efforts of American conservatives, having already severely restricted women’s access to safe abortions, to now start restricting women’s access to divorce, and particularly to no-fault divorce. It appears that many conservatives have never quite given up the idea that some people should inherently be the property of, and enslaved by, other people.

What is the cost, to all of us, when women have been so long and so severely oppressed by our ‘civilized’ society that they are compelled to seek security through their relationships, often with men who, due to their own trauma and emotional incapacity, offer them the absolute antithesis of security?

In Against Love, Laura Kipnis comments on this cost, describing what we want and hope for from love and relationship, and what we finally come to expect and settle for:

The most tragic form of loss is not the loss of security, but the loss of the ability to imagine how one’s life could be different.

And in a recent article, Lyz also weighs in on the cost of this ‘security’:

Rules and rigid definitions and codes of conduct are always supposedly done for [women’s] benefit. Get back inside the safety of the patriarchy… Too many women fall for it, because fear has been sewn into the female experience. We are taught to walk afraid through the world — with the knowledge that anything can and will happen to us if we are not protected.

But really, the safety being offered is a cage.

Fear IS sewn into the female experience, but I think the article by Lyz, and your own, skirt around why the female experience is one of fear, and why a primary motivator for a woman can be to seek security. We live in a Rape Culture and to envisage a world without rape, is to envisage a world of love. The culture that allows and enables violence against women and girls is the same force that has defiled the natural world. So what is the cost to all of us? – it will cost us the entire world and the Earth. But love and life will continue, nature is not vengeful and life will find a way to express love again.

So who poisoned those baboons, Renae?

Regardless of who poisoned the baboons ( i have no idea?) Dave’s comment here is correct: “This study conclusively demonstrated that patriarchal primate behaviour is not inherent or biologically-driven. It is all cultural conditioning.” It is culturally conditioned. Feminists identify rape as the cause of human suffering. Rape does not only shape sexual relations, because it ties the act of violation to the sex response, rape sustains the whole human cycle of violence and domination and hence trauma. By associating violation with orgasm and sexual gratification, it allows violence and domination to be fetishised, addictive and seen as exhilarating, sexy and macho. This is a big part of the reason why prostitution and pornography are an integral part of the war machine. Porn seduces men to violate. Against their nature. This is the socialisation of Masculinity which enables men to go to war, to kill and then to rape the women afterward. Exactly as we have witnessed in the past few months in the middle east and throughout history with agricultural expansion and genocide by colonialism.

Just for the record, the poisoning of the baboons was accidental. The alpha males, on a scouting trip, discovered a poorly-secured waste bin that contained the carcasses of cows that had died of bovine tuberculosis. The alpha baboons ate the carcasses and died from the disease. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC387823/

Yeah, it was accidental. The low status males and females lived, because the alphas did not let them eat the contaminated yumyums. The question remains, though, how well the gentler tribe would do if another troop waged war on them. Males can be violent for a reason. It’s a difficult balance.

Renaee: you seem to delight in channeling Andrea Dworkin. I find it repulsive, all this toxic dumping on the males of the species. And unhelpful. This is not an effing rape culture. There are rape cultures around the world, and this ain’t it. Do go traveling a bit. Grrr.

Not taking sides in any debates between readers, but I would request that everyone please remain respectful and try to appreciate WHY others have, for complex but understandable reasons, arrived at very different views.

I have no way of knowing why she arrived at — what looks to me like — toxic dumping on men. I do have a way of knowing that I don’t like it. ;-)

I don’t live in Canada, I live in Australia and I have no qualms in saying it is a rape culture, the legal fraternity, police and the politicians collude, whether consciously or not, to ensure that men are not prosecuted and women are framed as somehow deserving of it or asking for it – one or the other. We watch the court cases play out, it is excruciating. I don’t think this is a very different view – it’s quite commonly acknowledged among my women friends and with my partner when I talk to him about these matters too. I am not dumping onto men or the male of the species, but onto toxic masculinity, a force which harms boys and men as much as it does girls and women. How many men around the world are addicted to internet pornography and what a relief when the internet fails and they can no longer be exposed to the horror that passes as regular, everyday good ol ‘porn’, and how did we ever get to a place that such a thing exists, a kind of hell on earth, that is weaponised by the war machine to turn men into killers, as I said. Why is this perspective unhelpful – unhelpful to whom?

Unhelpful to the relation between the sexes. Isn’t it time to make peace? I used to snicker about “testosterone poisoning” too. Then I saw the damage such talk was inflicting on young men.

Here’s a thought. Sweden was not a rape culture. Few rapes (though I am not claiming there were none) and I have heard that their justice system was definitely not on the old boys’ side). Then they imported the rape culture, and now rapes are so through the roof they are lying and hiding the stats. Maybe raising young men to be too peaceful and gentle is not in our best interest either… (?)

My own perspective is that if in a culture a young woman can go skimpily dressed in public and near naked on the beach and is relatively certain nothing will happen, it’s not a “rape culture.” Relative to others. And should be appreciated for that rather than dumped on for not being perfect. Like the saying goes, perfect is the enemy of good…