Over the past few years, I’ve made some fairly strident statements about the current state of the world as I see it. They include:

- That our global civilization is now in the accelerating stage of inevitable, complete collapse that we will never even partially recover from. It will be a slow collapse, in multiple stages, over centuries, but by the end of this century the way in which the remaining humans (if there are any) will live will be utterly different from how most of us live today.

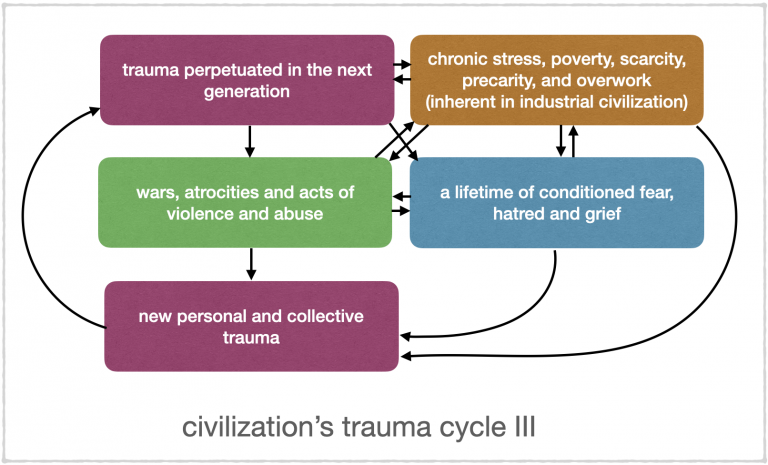

- That our species, uniquely and for quite conceivable reasons, at some point in our brains’ evolution became mistakenly and terrifyingly convinced of our ‘separateness’ from the rest of life on earth, rendering us emotionally and mentally damaged to the point that much of our behaviour now is a massively-destructive acting out of generations of accumulated trauma steeped in fear and hate.

- That we have no free will, and that our behaviour is totally a function of our biological and cultural conditioning, given the ever-changing and unpredictable circumstances of the moment.

A question that remains foremost in my mind is how our conditioning will compel us, individually and collectively, to respond to collapse. Since our conditioning varies greatly from person to person, our responses will likely vary greatly as well. And the “circumstances of the moment” will be very different at different times and in different places as collapse unfolds and accelerates over the coming decades as well.

What might some of our conditioned responses to collapse be, hampered as we now are by our species’ omnipresent mental illness and trauma?

As things get increasingly dark and hopeless, I think we are witnessing already the most common of these: sinking into depression, retreating into escapism, and simply denying these existential realities. And suicide is not an uncommon conditioned response for creatures in situations of unbearable overcrowding, stress and deprivation, and rates of suicide are soaring. Perhaps Aaron Bushnell is something of a canary in the mineshaft: His conditioning, like ours, drove him to do the only thing he could have done.

Many of us will continue to turn to the plethora of institutions and programs that have arisen in part to try to help us cope with everything falling apart — religions, spirituality, psychology, process-y methodologies and practices, drugs, rehab and anti-addiction programs, and perhaps even philosophy (eg stoicism). Some of them may seem to help for a while, but none of these institutions, programs and ‘therapies’ has a particularly enviable success record, and many of them arguably have done more harm than good to their ‘patients’. I have probably explored most of them, and found them all lacking.

No one can predict, of course, how, as collapse accelerates, we will each act out our conditioning and do the only things we could have possibly done in the circumstances.

All I can offer is my own story, how my own conditioning has led me to a particularly individual, and perhaps rather hopeless and disheartening, response to collapse. Your experience will differ, probably drastically, and none of what follows should be considered in any way as ‘advice’.

For a start, none of my attempts to ‘work on’ or ‘work past’ my trauma have ever helped me at all. In fact, dredging up the memories of the incidents and fears that likely conditioned me to be the way I am, seemingly just worsened the trauma, anxiety and depression. I remain unconvinced that therapies based on reenacting damaging and terrifying past events as a means of putting them behind us, have merit, at least not for me. The evidence is at best dubious and anecdotal. But maybe they help some people, or at least they may help some people believe they are coping better, which is worth something.

I also tried the pharmacological route (paxil — part of a family of now completely discredited drugs from the quack psychiatry toolkit). Never again (though the experience provided me with a number of really funny stories that people seem to like).

What I learned about myself (as has been explained in books like Against Empathy) is that there are situations in which my attempts to engage with situations that trigger past trauma simply render me paralyzed and dysfunctional. This is possibly connected with my body’s and brain’s retreat into severe depression in the face of extreme stress — depression from which I suffered for most of my life, but no longer do.

What I learned is that I just can’t afford to care too much emotionally about circumstances and about others’ suffering, when trying to do so just debilitates me. I learned instead to try to exercise a more “distanced compassion” in those circumstances — being attentive and thoughtful and hopefully helpful, without trying to “personally relate” to the suffering, and hence getting sucked into a downward emotional spiral myself. So now, when I face people suffering from severe distress, I ‘distance’ myself from it, by reminding myself this is their trauma, not mine, and that getting drawn into it is not useful to anyone.

As a result of this, I have on occasion been accused of being emotionally disconnected, disengaged, indifferent, and even dissociative. I have no idea whether those accusations are fair or not. All I know is that this is where my conditioning has taken me, and it seems to have made me, on the whole, more “of service”, less reactive, and more functional, than I used to be, when dealing with the kind of severe distress that we’re going to be facing all the time as collapse deepens.

Such conditioning obviously comes with a cost: I am likely less emotionally sensitive than I used to be, with fewer highs and lows. I do cry more than I used to, but they are tears of joy (often when listening to well-crafted and evocative music), rather than tears of empathy with others’ suffering or loss. I am very rarely depressed anymore (which may be just a biological effect of aging and more balanced hormones; I don’t know). There is less elation, but far more moments of equanimity and peace, which seems to me an excellent trade-off.

Looking back, and then to where my conditioning seems to have brought me to now, I can admit that, perhaps rather unusually, I have never really felt lonely, even in the worst times of trauma, solitude, and depression. I have no idea why.

And I have never really “missed” not having something, or doing something, or being with someone, when I no longer had that pleasure. I know I would enjoy having it again, or doing it again, or being with that person again, but “missing” those things just never comes up, and never really has, my whole life. And likewise, I have never really grieved or mourned the loss of anything or anyone. I cried when my dog died, but that was a purely instinctive, animal reaction, and then it was gone.

Maybe the fact that I have never felt these feelings means I am somewhat emotionally stunted, but if that’s so I think I have always been that way, rather than having become that way as a result of events that have happened, as a result of conditioning, or as a coping strategy. It seems to be more likely what is, and isn’t, in my DNA. I don’t know: In some ways I think I am a bit feral. I don’t think wild animals have these emotions either. And, perhaps like a wild animal, while I have an instinctive and terrible fear of pain, suffering, entrapment, and failure, I have absolutely no fear of dying. I don’t think I ever have.

In addition, I used to fall in love frequently, easily and deeply. And often it was with entirely the “wrong” people — a complete mismatch. I was still doing this a decade ago. And then a young woman told me, maybe at exactly the right time in my life to hear it, that I was a fool at heart. That I had fallen in love with who I imagined her to be. And then she told me who she (thought she) really was, and the types of guys she was drawn to fall in love with (and even introduced me to one of them). And she described how awful a romantic relationship between the two of us would almost inevitably be.

And strangely enough, thanks to this wake-up I was instantly “cured”. Ever since then, while I am still inclined to become infatuated (notably with exceptionally intelligent, energetic, curious, creative, imaginative, and strong people) I have never since fallen in love. And I don’t want to fall in love again. I no longer long for that feeling when nothing else matters except that love. Though damn, I remember those feelings. You never forget.

Now, everyone I meet has two ‘personalities’ — the one I can imagine them to be (and I have a pretty vivid and generous imagination), and the person they really are (who I appreciate I will never know and can’t even guess at). It’s really changed how I see people, and the world.

In addition, unlike a lot of people, I don’t particularly enjoy being loved. To me, rather than that being flattering or reassuring, it usually strikes me as a responsibility, something that (being basically lazy) I’ve never liked or wanted (though I have often been told I am one of the most responsible people they’ve met). Maybe it’s my large (hard-won, and then partially-lost) ego, that doesn’t need stroking, that has me preferring to be the lover rather than the loved. And I do still love people, places, wild things, creature comforts, all those ikigai things. I probably love them more than I ever have. But it’s very different from being in love.

As for all that ancient and endlessly-resurfaced trauma, slowly but surely its hold on me seems to have abated, though it hasn’t completely disappeared. Rather than repeatedly delving into how it arose and how it gets triggered, I have just kind of let it go, forgotten it. Kelly the genius psychologist says that I have largely ‘excised’ it, though I think she gives me too much credit. It might be mostly that my memory is not what it used to be, and it was never that good. In Africa, apparently, this is called “social forgetting” and has worked better in some groups dealing with major collective trauma than the “truth and reconciliation” approach of directly confronting it. Whatever works. We have no choice in the matter anyway.

So I guess that’s where my conditioning has taken me. Never lonely, never grieving, never afraid of death, but fearful of pain, of feeling trapped, and of failure — that I suppose is biological conditioning. No longer a fool for love (but more enamoured of simple pleasures), slowly letting go of trauma, rarely depressed, less reactive, and far more equanimous now — that I suppose is cultural conditioning.

How has that conditioning equipped me for facing accelerating collapse, and the very challenging times ahead? Not very well, I fear. The realization of the imminence and inevitability of civilization’s total collapse was easy for me to handle, perhaps because I just don’t seem capable of grief. But I have never handled extreme stress well, so as things worsen and as compounding and increasing crises become the order of the day, my conditioning has not prepared me to handle these things at all well.

How do I think others’ conditioning has equipped them to face all this? I have absolutely no idea. My study of history (and the stories from my grandparents about the Great Depression) suggest that when things get dire, it’s amazing how quickly people will learn and do the things they need to learn and do, physically, to cope with the situation.

But in past crises, people could always look forward to (and imagine) a future when things got better again, and I don’t think we’ll be able to do that this time. When it really sinks in that we’re living in end times for our astonishing civilization culture, I’m not sure our conditioning will allow most people to handle that emotionally at all well. The latest post from Indrajit Samarajiva, perhaps, gives us a clue:

This is where I live… In the land of the dying, where the land itself is dying, and we are but witnesses. Mute or unmute, it makes no great difference now. We are all dying people, in nations dying one way or another, in a world that’s dying too. As my Achchi [grandmother] was holding me she told me clearly that we all have to die. And it’s true. It’s just that ‘all’ means a lot more at this particular hinge in time, when the doors come off. My Achchi, for one, is ready to go. I envy her in that. I’m not ready at all.

But I really have no idea where our conditioning will take us from here. My fascination with chronicling our civilization’s collapse, which I’ve pursued now for over two decades, partly stems from wanting to know the answer to this question.

I’m prepared to be surprised.

I hope you’ll forgive me if I call this brilliant. I am sure there are others but you have described in detail how I feel and I thank you for that as I had assumed I was the only one.

For some reason I keep returning to your essays. What am I looking for? What would Dave say–a more beautiful question? You often answer your own questions with “I have absolutely no idea.” So why the hell? But deeper, deeper into the well of raw feeling inquiry: what is this …nothingness? Collapse is the meaningful story of guilt and failure –the myth of our time. Surely it has to mean something! Job falling on his sores, cursing the Ineluctable Implacable of meaning. Just escapism, projection? Ex nihilo nihil fit.

Dave, this is been on my mind a lot. The whole “harm reduction” debacle. Yes, it made sense way back when to try. But the whole thing seems so fatally screwed up to me. Yes, you can save lives of Skid Row drunks if you give them free safe booze in prohibition, and they are less likely to go blind from bath tub gin… BUT aren’t you enabling a self-destructive habit?

Or to return to fentanyl et al, aren’t you enabling the sale of the safe drugs back into the street since they fetch a premium, and then for that price, get something with more oomph albeit risky? Aren’t you creating a lure for outlying kids to flock down and get a little too? And aren’t you creating yet another non-profit industry thriving on the continuation and intensification of the problem?

Been reading several articles on what is happening, and since the epicenter is in Vancouver these days, I thought… I would love to hear Dave’s thoughts on this.