Since I’ve come to the (tentative) conclusion that we have no free will (and that in fact there is no ‘self’ to have free will), it’s utterly changed the lens through which I see the world. I now see that our behaviour is completely conditioned by our biology and our culture, given the circumstances of the moment, and that ‘we’ have no ‘choice’ but to do what we do. We are all doing our best (though that is often, seemingly, pretty awful), and no one is to ‘blame’. For anything. Even though our conditioning, so often, causes us to inflict, and to suffer, horrible violence and trauma.

As I’ve internalized this, my writing has morphed from describing what I think ‘should’ be done to instead just trying to understand why (ie as a result of what conditioning and what circumstances) things are as they are. So I now use the ‘reminders’ list above, to cope with the accelerating collapse of our civilization and its component systems, instead of any action or preparation list. We can’t act, after all, other that how we’re conditioned, and we can’t prepare for something we cannot possibly predict.

Still, even this list is really wishful thinking. I cannot ‘choose’ to do or not do these things. I can, perhaps, by keeping it in front of me, track the degree to which my behaviour does or does not align with these ‘reminders’. If that helps me to cohere somewhat to these reminders, it is only because that is what my conditioning already inclines me to do. Everything is determined (ie a consequence of our conditioning, and of the circumstances of each moment, neither of which we have any agency over), but nothing is determinable (ie predictable, because, unless we are gods, we cannot know how we are next going to be conditioned, nor what the circumstances of each moment will be).

The other day I watched a concert by Shari Ulrich, who was performing with Cara Luft, and I was particularly blown away by their performance of Shari’s song A Bit of Forgiveness. It’s a song about divorce, but its message runs much deeper:

If I had wishes, only three, well I’d use them up so easily,

I’d need at least a dozen, maybe more;

Surely first would be peace on earth, and probably third that I hadn’t hurt you —

Seems in every wish there’s a bit of forgiveness…

If I were granted all my wishes, none would be for gold or riches —

I’d need at least a hundred, maybe more;

Fourth or fifth I can’t admit to; down the list is that I didn’t miss you;

Seems in every wish there’s a bit of forgiveness.

That got me thinking about wishes, regrets, hopes, and some of the ‘soft skills’ I have (been conditioned to) try to cultivate, in point 3 of my ‘reminders’ list — specifically acceptance, forgiveness, and gratitude.

What are our ‘wishes’, anyway? They are, mostly, hopes for the future and regrets about the past.

How crazy is that? Hoping the future might be something different from what it inevitably will be (once the uncontrollable conditioning and uncontrollable emergent circumstances play out), and regretting what inevitably happened in the past.

So why do we do it? It is, of course, our conditioning. We get a dopamine hit anticipating something (either good or bad) happening in the future, as a means of conditioning us to behave in ways that will bring about, or avert, what is anticipated. Though only humans, it seems, do so for a period in the future so far ahead that what will actually happen can’t possibly be predicted. Wild creatures will only anticipate a moment or so into the future (being given a treat, for example, or being eaten by a tiger).

It is our imaginations that allow us, uniquely, both to imagine what ‘might’ happen in a distant future and to regret the past (ie to imagine how the past ‘might have’ been different). Neither of these imaginings has any evolutionary value whatsoever. We won’t ‘learn’ from a past mistake by imagining ourselves not having made it — if it is in our conditioning, given the future circumstances, we will make that mistake again.

Likewise, we can imagine a whole range of potential future outcomes, but none of this intellectual cogitation will change our behaviour one iota from what it was already inevitably going to be. Its only ‘value’ is to ‘make sense’ of what happened, after the fact. And that sense-making, based on the illusory sense of free will and control, is inherently totally flawed, since it presumes there is more than one possible outcome that our ‘selves’ can somehow influence.

That’s why I argue that the brain’s development of the sense of having a self with some degree of free will and control over the body it presumes to inhabit, is an evolutionary misstep, a misunderstanding of the nature of reality that grew out of the entanglement of our human brains’ circuitry, imagining things to be ‘real’ when they are not. The evolution of this misunderstanding in the entangled human brain is completely understandable, but such a misunderstanding is completely impossible in the brain of any creature that simply ‘knows’ the absolute difference between reality and an imagining. So our possible futures are, to us, ‘real’ possibilities, worth wishing and hoping for, and what might have ‘really’ happened in the past that did not, gives us something to regret. No other creature, I believe, is so afflicted.

Lately when I first climb into bed at night, and peer out the window at the astonishing panorama of lights and beauty that stretches as far as the eye can see, I have found myself filled with an overwhelming sense of gratitude.

But why? If what has happened is the only thing that could have happened, what in the world do I have to be grateful for? That my life is so easy and peaceful, and not filled with fear, anguish, rage, violence, deprivation and trauma like so many others’? But it couldn’t have turned out otherwise. Why be grateful for what didn’t happen, for what isn’t? Gratitude, it seems, is a kind of feeling of relief, that things didn’t turn ‘otherwise’, which they could never have done.

So the joyful puppy that is rescued from a life of misery is not grateful for having been rescued, because it ‘understands’, thanks to its ‘clear-headed’ unentangled brain, that it could not possibly have been otherwise. It is joyful for what is, not for what ‘might’ have been that is not.

My poor entangled brain, however, can’t make such distinctions. It is full of joy and relief and gratitude at my current circumstances. It’s a form of insanity, really, but there it is. I laugh at the sheer folly of it, as I lie in bed with tears in my eyes. The feeling of gratitude does not abate, whatsoever, despite my intellectual ‘realization’ that that feeling is unwarranted. That it’s this body’s conditioning, with its befuddled brain, playing out the only way it possibly could. Given the amazing, wonderful circumstances of this beautiful moment I am so helplessly, hopelessly, insanely grateful for.

And it’s the same, I would assert, when it comes to acceptance, and forgiveness, and all those other sort-of-equanimous characteristics that we esteem so highly through the fog of our brains’ sense-making. They are misplaced feelings and sensations, but still our confused, entangled brains cannot help but feel them.

We think of forgiveness, often, as an act of charity, of generosity — as a virtue. It opens the door to reconciliation, to “coming to terms”, and to acceptance, we think. And of course, if that’s what we think, and want to believe, it can seem to achieve those ends. We even use the term “forgive and forget”, whereas for wild creatures (and apparently for some human cultures that have moved past trauma without confronting and insisting on acknowledgement of guilt and blame and responsibility and regret and apology and atonement), there is only forgetting. And for them, forgetting is simple — after all, it is the only thing that could have happened, and it is done, past. There is nothing for them to ‘hold on’ to.

I’m not saying that our insistence, in most human cultures, on calling past actions to account and confronting them is wrong. Given the way our brains work, it is, for most of us, the only way we can deal with what we imagine and judge to have been avoidable, deliberate, unjust, unforgivable, unforgettable actions, and hence hopefully move past the trauma that resulted.

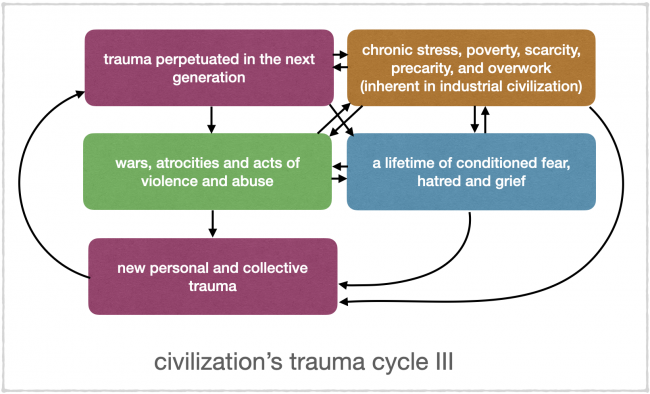

Except there’s lots of evidence that it doesn’t work, as I’ve tried to explain in my writing about the trauma cycle:

Given this cycle, and our brains’ (IMO mistaken) insistence on ascribing free will and choice to actions past and imagining what might otherwise have been, the best we can possibly do is seek and offer forgiveness — and be grateful for what we imagine might have but did not happen.

But this never comes easily: I would never attempt to argue that those currently suffering genocides, wars, prisons and other excruciating forms of severe and chronic violence and abuse, should or could be anything but outraged, vengeful and hate-filled as a result of their situation. The human trauma cycle self-perpetuates, and we have been dealing with the consequences since the dawn of human civilization. The thing about vicious cycles is that there is no way out. Until our civilization collapses, anyway, and until enough time passes that no one remembers, even in their DNA, the trauma that accompanied it.

Acceptance, forgiveness, and gratitude, then, are really more what is left in the absence of fear, anxiety, rage, hatred, grief, resentment, jealousy, envy, shame, blame, disgruntlement, outrage, indignation, the bristling at perceived unfairness or injustice, and the trauma that their acting out produces — all those emotions that are roiled up uniquely in the entangled human brain. If we ‘feel’ accepting, forgiving, and grateful, that isn’t because we are virtuous; it’s because we have had the good fortune not to have been (at least recently) on the receiving end of unbearable, unforgivable, unforgettable, violent events and actions.

Except there is no ‘good fortune’ — there is only what was inevitably going to happen anyway.

Should we aspire to be (more) forgiving, accepting, and grateful? Why not? At least when we try it seems to help us get along better with other humans, and make us feel a bit better, as we struggle together with the human brain’s unique miasma of entangled emotions, and our uniquely human incapacity to separate what is ‘real’ from what’s imagined. Not that we have any choice in the matter. It’s hard to give, it’s hard to get, but everybody, it seems, needs a little forgiveness.

Watching our behaviour, wild creatures must be wondering what can possibly be going through our heads.

Luckily for them, they can’t imagine.

Agree that gratitude can be immense but is just a relief really, what is left in the absence of all those negative feelings and thoughts, not some noble state or practice to aspire to. but it can brew up a feeling of awe and bring tears. I am glad you get to look out at such an epic night time panorama. I know this feeling of being so grateful/relieved for a soft warm bed!

The puppy joyful for what is, not for what ‘might’ have been – that sums it up, and we always project misery onto animals in pain, we feel outrage for them. they are in pain, not suffering, there is a big difference. They don’t have that ability to imagine it could or should be different so they don’t suffer the ‘second arrow’ .

Hi Dave,

I meant to comment on self a while back and this is a second chance. Agree that free will (dependent on definition) is minimally vastly overrated. We make decisions/choices most of our waking lives, but these are ’caused’ by heredity (not just genes), cumulative experiences since conception, and external conditions at the moment. As a physicalist (energy/matter/information) what else could be involved?

As to self, I’ve no problem with that as the internal drivers mentioned above are all embodied. That’s all I need for my personal self to be fully real. If I itch, I scratch. If I eat/drink, I’m sustaining myself. I see no problem with this down to earth conception.

Cheers on the downslope,

Steve