What is a “belief” anyway, and how does it get “there”?

The word belief comes from the old Germanic root that also gives us love and it originally meant something (impersonal) we care about and trust strongly.

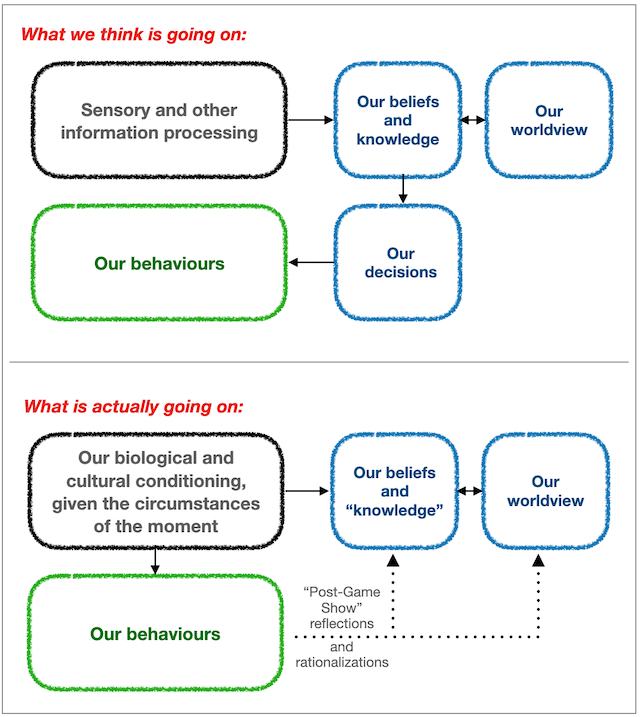

I would argue that beliefs are unique to the human brain, and that they are the building blocks of our worldview — the coherent sense-making lens through which we judge, filter and assess events and information to assign them meaning.

Wild creatures have no need for beliefs, judgements and abstract sense-making. Their brains were designed for feature-detection, in order to inform their instincts. If they’re conditioned by humans, they will (provided there isn’t too long a gap between the prompt and the reward or punishment) behave in a way that anticipates a reward or punishment (dopamine again), and do what has been rewarded (ie maximize pleasure) and avoid what has been punished (ie minimize pain). There is no need for a worldview or a set of beliefs. As Melissa Holbrook Pierson explained in The Secret History of Kindness :

This is the basis of my dogs’ storied love for me, their one and only. Only I know the real truth. It is not this Melissa they love. If they bark menacingly at someone who approaches, they are not doing it to ensure my safety. There is but one thought in their minds: do not harm this person, for she is my most valuable possession. My large Swiss army knife, the one with all the extra attachments…

The same law of behavior affects all creatures’ actions: we do something, it produces pleasure or it produces pain or it produces nothing, and the result determines whether we continue doing it, stop doing it, or do it differently, and these are the only options.

If wild creatures have no need for beliefs or a worldview, do humans? I have recently come to know some humans who assert it is obvious that nothing is, or can be, known, and that thoughts and beliefs may arise, but they have no consequence, they are just what Melissa calls a “retroactive narrative” to try futilely to make sense of our behaviour.

But there is no homunculus, no coherent, controlling ‘self’ responsible for our behaviour, which is simply what has been biologically and culturally conditioned, in an unimaginably complex process that we cannot possibly make rational or emotional sense of. Our beliefs and worldview and explanations for our behaviours are just the post-game show in which the pundits, not knowing anything more than anyone else, speculate on what happened or might have happened. Just meaningless blather.

So why then do our brains seemingly use up so much energy developing, reinforcing, defending, and arguing, our beliefs and our worldviews?

The answer, apparently, is that for reasons we cannot know, they simply evolved to do this as they became large enough to have the capacity to do so (ie very recently in the time-frame of life on earth). Just nature trying something out to see if it creates a ‘fitter’ species. So we formulate beliefs and worldviews and use them for our personal and collective post-game chats on what we, and what others, did, and why possibly they did so. The assumption is that from these ruminations we might ‘learn’ something that will help us survive and thrive in a similar future situation.

But we’re caught in a loop, because when we actually face that ‘future’ situation, it will be our conditioning, not our ‘learning’, that determines our behaviour. Then we will further ruminate on what we did, and whether or not we ‘learned’ from the previous ruminations, in the next post-game show. So, other than the sense of satisfaction or anxiety we get from these ruminations, our learnings do not change our behaviour. They are essentially (like most post-game shows) a useless waste of energy, but then our large brains have lots of excess capacity, and they have energy and capacity to spare. So, nature seems to be saying: Let the pundits in our brains ramble on; they’re not doing any harm, and no one’s paying attention anyway. This might turn out to be a useful evolutionary adaptation.

We will do what we will do based on our biological and cultural conditioning, given the circumstances of the moment. Our ‘learnings’, beliefs and worldview will have nothing to do with it. So, for example: If we are walking at night and someone startles and terrifies us, and we happen to have a weapon of some kind on hand, and we use it, or we don’t use it, then those behaviours (both the lurker’s and ours) are completely the result of our conditioning. We will rationalize it on the post-game show, but our beliefs and worldview, featured on the show, will have absolutely no bearing on our behaviours. Our thoughts and beliefs don’t produce our behaviours, they reflect our behaviours.

So, now, whether or not our beliefs actually affect anything, how is it they get into our brains in the first place? If they’re just musings in the post-game show, how is it, for example, that you might construe a certain behaviour as a savage act that requires punishment and incarceration, while I could construe the same behaviour to be a valiant act of resistance and self-defence? And if we talk about it, what is the process by which we will, or will not, change our ‘minds’ (our beliefs) about the incident?

The prevailing theory seems to be that, before we have thoughts about and have formulated a ‘belief’ about some new subject, we will have an ‘open mind’ about the subject, but once we’ve formulated a belief, we tend to defend it and resist changing our minds about it, more and more as time passes, unless that belief has been ‘successfully’ challenged by very compelling new ‘evidence’. But in many cases, like lawyers looking at similar precedents, we are rarely really going to have an ‘open mind’ on any subject, because, even if the subject is new, there will be similar subjects within our overall worldview where we have already formulated a belief. So, for example, if we have formulated a belief that Russia is a threat to freedom and democracy, we will likely be predisposed to believe that China, or any other country we have no personal knowledge about, is likewise a threat, if someone suggests that it might be.

But where did that xenophobic belief come from in the first place? It came from our conditioning. This is a different kind of conditioning from the biological and cultural conditioning that determines our actual behaviours, but it is conditioning nonetheless. In the post-game show, when we are ruminating on something that happened, we will often try to sync up our beliefs and behaviours, either by adjusting our beliefs so that our behaviours ‘make more sense’, or by regretting or hoping to change our future behaviours because they seemingly are not in sync with our beliefs. But that syncing process achieves nothing, other than perhaps making us feel better (justified) or worse (disturbed) about ‘our’ behaviours or our beliefs.

In many cases, such as with our beliefs about current wars, most of us won’t have any ‘related’ behaviours, other than stating and justifying our beliefs, and perhaps arguing with someone or joining or opposing a protest movement. In those cases, it is highly unlikely that we will ever change our (or anyone else’s) mind about the issue, since any new contrary ‘evidence’ will be viewed through our existing worldview which will be resistant and skeptical about the credibility of that evidence. It will take something really major to shake that resistance and skepticism.

So let’s consider some examples of how this plays out:

I was brought up (conditioned) to believe that fluoridation of water was a useful and harmless way to ensure that people who didn’t use fluoride toothpaste would avoid tooth decay, and also as an extra layer of protection for my own teeth. My conditioning was to trust public health officials with no evident axe to grind on the subject.

I knew people who were conditioned to believe fluoridation was a government or “Communist” conspiracy to deliberately poison the water to reduce the population’s IQ, and others who were conditioned to see it merely as an unwanted infringement on their personal “freedom of choice”.

The science favouring fluoridation at the time was clear — it reduced tooth decay in towns that used it and there were no studies confirming negative effects on physical or mental health. The “other side” actually entrenched my support for fluoridation with their hysterical fear-mongering. For example, Paul Gosar, an American right-wing politician who has apparently never encountered a conspiracy theory he didn’t like, and a dentist, completely reversed his position in recent years, and now gives speeches to right-wing groups predisposed (conditioned) to distrust government on every subject, opposing fluoridation of water supplies in towns where he personally championed and oversaw the introduction of fluoridation twenty years ago. Nothing more annoying than a born-again evangelist.

Fast-forward to the present, and I see a video and article by Michael Greger, a medical doctor who believed fluoridation was safe as I did for the past fifty years, but has just changed his mind. He just follows the research, and what he has read recently has given him pause, at least when it comes to exposure to fluoride for pregnant women. I have come to trust him and his non-profit for his independence, thoroughness, and honesty (ie I have been conditioned to believe what he says), which is:

The tendency to ignore new evidence that does not conform to widespread beliefs may be impeding our response to early warnings about fluoride as a potential developmental neurotoxin. But some are just so fixed in their views on fluoridation that they won’t reassess their stance, no matter what the latest research might show… It’s worth remembering that the science surrounding the neurodevelopmental hazard of low-level lead exposure [from leaded gasoline etc] was also bitterly contested using the same kinds of arguments we see today in the fluoridation debate.

What’s going on here? He’s readily admitting to have changed his mind, and is discouraged that his professional colleagues are refusing to change theirs “in the light of new evidence”. But, just as with the “harmlessness” of smoking, and the rejection of climate change as a conspiracy theory, it’s really hard to get people to change their beliefs once they’re embedded in a worldview. Still, Michael changed his mind, and he has changed my mind. How? It’s our conditioning. We have both been conditioned to keep an open mind on things. Thanks to my conditioning, I have changed my mind on lots of things. Many other people I know are conditioned to see changing one’s mind as a sign of moral or intellectual weakness.

So, bottom line, our conditioning determines our behaviours (given the unpredictable circumstances of the moment). Our conditioning likewise determines our beliefs. But the two are often not, and need not be, in sync. After all, our beliefs just reflect our behaviours; they don’t produce them. And our capacity and predisposition to change our beliefs is also conditioned.

I’ve tried to capture this in the diagram above. Yeah, I know, I’ve been conditioned to try to sketch out visuals that reinforce my words, which is not always helpful.

Let’s look at another example: Until perhaps 20 years ago, I had no strong opinion on any of the conflicts in the Middle East. I just didn’t know enough to have a real opinion. No one I knew, or had ever known, had a strong opinion. The information sources I read expressed conflicting opinions on the causes of the conflict. So on the subject I had just one strong belief: That all sides should be working towards a lasting peace, which was (I believed) in everyone’s best interest. I had always been conditioned to believe that war is never an answer to anything.

I had also been conditioned to believe that no one should live under an oppressive regime. The information I was exposed to led (conditioned) me to believe that the Russian government was no longer oppressing its people (though the jury was out on Putin), and that China’s government still was oppressing its people (there has always been lots of propaganda out there on this subject, for a host of reasons which, at the time, I never understood). And that Israel, perhaps still understandably struggling with the horrible trauma its people had endured, was seemingly oppressing the people of Palestine. Yet I still didn’t know enough to have a strong opinion on the occupation or on the wars. I was, as I had been conditioned, keeping an ‘open mind’ on the subject.

But over the past 20 years, it became increasingly obvious, from what I read, that the people of Palestine were being horribly oppressed. I began to learn that the media I had always been conditioned to believe, were two-faced when it came to oppression. I started reading different information sources and was horrified. What I thought was mostly partisan rhetoric (the use of the terms like “apartheid” and “open-air concentration camp”) were now seen as accurate descriptions of the life of Palestinians. What were euphemistically referred to in the mainstream media as “settlements” in the occupied territories were now seen as what they were: the destruction, theft and occupation of one nation’s property by another nation.

This was not hard for me to come to believe, because I’d been conditioned to keep an open mind, and because I had no strong pre-existing beliefs to overcome.

So when the attack by Hamas occurred last October, followed by the retaliatory genocide by Israel, I saw it through a completely different, conditioned, worldview ‘lens’ than that of almost everyone I encountered. I was shocked by their reaction, and they were, in some cases, shocked by mine. I was filled with dread because I ‘knew’ that in previous conflicts Israel had exacted a >10:1 punishment on the Palestinians and the neighbouring Arab states. And I ‘knew’ from recent reading that Netanyahu was a corrupt, traumatized, and mentally unstable man, looking for an opportunity to distract attention from his many domestic criminal activities.

I did not expect an all-out genocide, but neither did I rule out the possibility. I was surprised, but not entirely surprised, that the media came out so stridently in favour of the genocide, including giving instructions to their journalists on what they could and could not say about the genocide (including “don’t call it a genocide”). I was surprised, but not entirely surprised, that the so-called “progressive” parties in all western countries unreservedly supported the genocide — that is how they had been conditioned, and at some point, somehow, my conditioning had taken a very different path.

And I was surprised, but not entirely surprised, that the people I know almost all do call it, and see it as, a genocide — one of the ugliest and worst atrocities of the past century. The people I know, after all, have conditioned each other, and have increasingly been conditioned by shared information sources that diverged from those consumed and propagated by the majority of western citizens, including the majority of “progressives”.

Last week in our apartment’s elevator I encountered a man who had clearly just returned from a Free Palestine demonstration. He was evidently a co-organizer, judging by the demonstration supplies he was carrying. He looked nervous when he saw me — understandably given the strong opinions on the subject. I reassured him that I supported his cause and thanked him for doing what I suppose I do not feel strongly enough about to do myself — It’s been 50 years, I told him, since I was part of an anti-war demonstration.

He looked at me quietly and said: “I have no choice but to be out there, every day, demonstrating for peace. I have lost 55 family members in the war, including, last week, twin baby girls.”

So there is the evidence. If I’d heard it indirectly from a televised or recorded speech, I might be able to discount it, if it were too much of a challenge to my worldview (which it isn’t). But this guy was my neighbour. He had no reason to bullshit me. I wondered, as I was left speechless as he exited the elevator, how could anyone, hearing this from a horribly distraught man two feet away, speaking directly one-on-one, not have their mind changed by this simple ‘evidence’?

A couple of days later I was speaking on the phone with someone I know who has been conditioned their whole life (by family, friends, circumstances, environment, and the media they consume) to be quite conservative and untrusting in their thinking and beliefs (at least on most subjects). We got to talking about politics, which is always precarious, but there’s enough mutual respect to do it. I mentioned the genocide in Palestine. They objected and said they supported Israel because, you know, the usual arguments about “right to self-defence” and the October “provocation” etc. I relayed the story about my exchange in my elevator. There was a long silence. There was a “wow”. And then there was a quick change in the subject.

Have I conditioned them to waver in their support for the genocide? Maybe. Probably not. Once they are safely back in the echo chamber of like-minded thinkers and reassuring propaganda, there will be a rationalization about why it still somehow makes sense to support that genocide, and to deny it is a genocide. Maybe there will be a rationalization about how the guy I met in the elevator probably made up the story. Maybe the story will just be conveniently forgotten, because it doesn’t ‘fit’ with their worldview.

A worldview is a kind of edifice. Once you undermine part of it, the whole thing can become unstable and start to fall apart, and that is understandably terrifying. How can one admit that a cornerstone of one’s beliefs was horribly, maybe even criminally, wrong? Easier to double down and retrench, as Biden has been doing, month after month, slowly destroying the party that foolishly nominated him. It’s hard to change your beliefs, and your worldview. It’s hard to admit you were wrong. You’re often left vulnerable, full of doubt, shame, or guilt, and perhaps questioning everything else you believed. Perhaps that’s why my parents were so determined to condition me to be open-minded, to challenge everything I was told and believed. They wanted me to be resilient.

Maybe the elevator guy’s story, even re-told indirectly, will change some people’s beliefs. Maybe it’s that rare bit of ‘new evidence’ that pushes someone past a tipping point they were already reluctantly nearing. It’s hard to change your beliefs, but it’s not impossible. It’s all conditioning, and one can always be ‘re-conditioned’.

That does not mean there will be any change in behaviour, though. The conditioning that determines our beliefs and the conditioning that determines our behaviour is very different, though it might sometimes ‘rhyme’.

The question then remains: Why is it apparently in our nature to be so reluctant to change our beliefs and our behaviours, at least once they are established?

I have no answer to this. This ‘natural conservatism’ apparently evolved in our species’ behaviours and beliefs, and not necessarily for any ‘reason’. Throughout the world and throughout our species’ history, xenophobia, the fierce adherence to beliefs long after their credibility is threadbare, and a reluctance to change our minds or our behaviours, seem to be ingrained in the human species. Maybe that is the downside of conditioning — it’s a slow process, hard to do and to undo.

I had thought that when the sheer obviousness of the climate crisis was shown to the world, as it has been relentlessly for 60 years now, that beliefs and behaviours would quickly change. One more thing I was wrong to believe, and reluctant to give up believing. So now it’s no longer a crisis, it’s a collapse, and still the old conditioning holds sway. No amount of new evidence, it would appear, will compel most people to change their beliefs and behaviours. Collapse is already well advanced in much of the Global South, and it’s advancing steadily. At the speed of light, even, compared to our conditioned responses to all the terrifying new evidence.

At least, that is what I have been conditioned to believe.

My capacity for compassion, for everyone, stems I think from an appreciation of how much of our behaviour, and our beliefs and worldviews, stems from conditioning. That appreciation even enables me to be compassionate towards those who are incapable of feeling or showing compassion to others. I still get angry, and fearful, and sad, and this appreciation of why things might be so fucked up the way they are is small consolation. But it does enable me to maintain my sanity.

Most of the time, anyway.

I just popped in to share this link, I picked up at Morris Bergman’s blog. I thought y’all may find it interesting.

Empire Managers Explain Why This New Protest Movement Scares Them

“The US secretary of state and a Bilderberg surveillance tech oligarch have both made some very interesting admissions about the burgeoning protest movement against the US-backed slaughter in Gaza and the problems it poses for the empire they help run.

During a vitriolic rant about university demonstrators at the Ash Carter Exchange on Innovation and National Security on Tuesday, Palantir CEO Alex Karp came right out and said that if those on the side of the protesters win the debate on this issue, the west will lose the ability to wage wars.”

https://hotcopper.com.au/threads/middle-east-war-expands.7662971/page-2313?post_id=73756546

Dave, your post is definitely a timely one for me. I just finished reading Richard Crim’s latest Crisis Report (https://smokingtyger.medium.com/the-crisis-report-37-2ed683ea7704) on climate change. It makes one wonder how even climate scientists can be resistant to the findings of paleoclimatology and recent research on the potential impact of CO2 levels on stratocumulus cloud cover. In summary, the 2.5 degrees Celsius warming expected by mainstream climate models over the next century may, if Richard Crim’s synthesis of the paleoclimatological data and latest stratocumulus simulations is correct, actually be closer to five times that due to the warming impact of CO2 and the related reduction in stratocumulus cloud cover. However, it’s just not something that the mainstream is willing to consider seriously yet. Or should I say it’s not something that they’re conditioned to accept yet? Old conditioning dies hard, as you illustrated. I, on the other hand, am conditioned to be more open-minded to this evidence, though what good this may do me or anyone else is unclear.