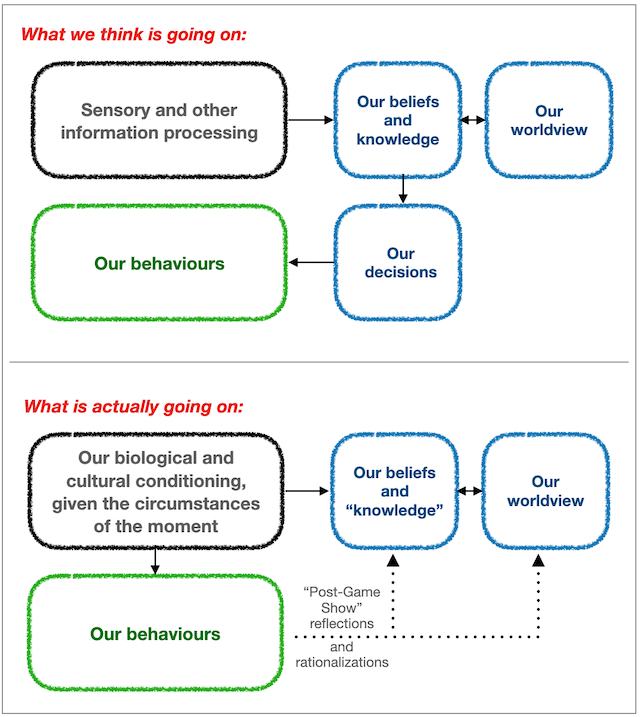

The ‘model of reality’ referred to in this article is shown in blue on the diagram above.

So ‘I’ apparently ‘wake up’. A conditioned series of biological responses increases the blood flow to certain parts of this body and brain, and increase cortisol production. There is a whole series of ‘preparatory’ chemical changes in the body that precede awakening.

Like a lot of people my age, I woke up several times the previous night. A part of the body (the Reticular Activating System or RAS) at the top of the spinal column flicked a chemical switch each time, alerting the body of the need to arise and visit the bathroom. The RAS also plays an essential role in morning awakening, going around flicking a number of chemical switches in sequence.

It’s fascinating that there is extremely little research on the subject of awakening, and in what little there is, there is seemingly no definition of ‘consciousness’ — it seems to be taken as some kind of magic state that needs no definition or scientific explanation.

I lie in bed supposedly ‘deciding’ whether or not to get up now, but ‘I’ am not making that decision. In fact, it seems that the complete reconstruction of ‘me’ is part of the process of awakening. That reconstruction is an involved set of chemical reactions connected to memory and other neurological ‘circuits’ in the brain.

So apparently this body’s conditioning is now compelling the body to get out of bed and to do certain things — put on the kettle, make the bed, check for any urgent texts or emails, and make another visit to the bathroom. Even the email check is not ‘my’ decision. It’s autonomic conditioning, or what, because we have no idea what is actually entailed, we fuzzily describe as ‘habit’.

There are of course thoughts that accompany this sequence of the body’s conditioned behaviours. But they are not ‘my’ thoughts, and they do not affect the body’s behaviours. They simply attempt to ‘make sense’ of the behaviours after they’ve been enacted. This mental model rationalizes: Why did I bother to check email when there’s nothing urgent happening in my life that would require this? Why do I put the kettle on before versus after making the bed? ‘I’ presume that ‘I’ am having these thoughts, and that they are affecting ‘my’ decisions which are controlling ‘my’ body.

But none of this is true. Science has pretty conclusively shown that there is no ‘me’, no ‘self’, no ‘decisions’ made by the self. This is all just stuff that the brain invents — a model of the world in which it attempts to make sense of what has already been ‘decided’ by the body entirely on the basis of its biological and cultural conditioning, given the circumstances of the moment (which, today, include a zoom call scheduled to start an hour from now).

So the biological conditioning compels this body to don a robe (in response to the morning cold), while its cultural conditioning compels it to put on a shirt and pants (appropriate for the zoom call). A conditioning compromise is reached: The robe is worn over the shirt and pants (the patio door is open and there’s a strong breeze), and the robe will be removed and the patio door closed when the zoom call begins.

Another complex ‘decision’ of the body is to brush its teeth before making the cup of tea: Teeth need to be brushed for preventative health reasons and because of morning breath that smells and tastes bad, but the toothpaste affects the flavour of the tea. Lots of (quickly abandoned) thoughts about this, but, again, they’re all just after-thoughts, not bearing on the ‘decision’, and not ‘my’ thoughts (since there is no ‘real’ me — that’s just a model the brain has concocted to rationalize and second-guess the ‘decisions’).

But we’ve missed a step here. The above rationalizations presume there is a singular ‘conscious’ body ‘making’ these decisions in some kind of holistic way. We’re back to the mystery and magic (I’m being sarcastic) of ‘consciousness’, which doesn’t stand up to even the most rudimentary scientific assessment of the decades of psychobabble that led us to simply presume there ‘is’ consciousness, just as it has led us to presume, similarly without evidence, that there is a separate ‘self’, a ‘me’, a little homunculus inside us making egoic decisions and suffering from various mystical Freudian mental disorders (OK, I’ll stop with the assault on the pseudosciences now — I can’t help it; it’s just my conditioning ).

The toothbrushing decisions were not made by ‘the body’, some kind of cohesive ‘individual’, any more than they were made by ‘me’. So what actually happened to prompt these apparent ‘decisions’?

What happened is basically the same thing that happens when you drive your car or engage in other behaviour that we label as ‘subconscious’. Your body chemistry, your neurons, your muscles, all of the trillions of elements that comprise ‘your’ body do precisely what they have been conditioned to do, responding autonomically to signals. This is no different from what happens when your body chemistry and physiology regulates your breathing, your heart rate, and all the other functions that do not require ‘conscious’ thought.

Miraculously, none of this requires ‘our’ ‘conscious’ intervention, or centralized ‘control’. Just as well: Neuroscience studies suggest that the ‘conscious’ mind is capable of processing only about 40 ‘pieces of information’ per second, compared to the 11,000,000 pieces of information per second processed ‘subconsciously’. And that’s just information processed by the brain‘s neural networks — the body processes much more information without any interaction with the brain at all. (For example, when our foot steps on a tack, the pain signals are transmitted to neurons in the lower spinal column and ‘it’ quickly ‘instructs’ the leg to ‘instinctively’ lift the foot up to alleviate the pain. This all happens long before any signals reach the brain; in fact, if the brain had to be involved, the injury would probably be much more severe.) And all this ‘processing’ is entirely conditioned.

So it’s not ‘me’ making any ‘decisions’ about anything this body does or does not do. And it’s not this ‘body’ making the ‘decisions’ either. This ‘body’ is just a collective label we put on the complicity of trillions of creatures that, for the moment, appear to comprise it. It is the conditioned behaviour of these trillions of creatures that collectively appears to be the ‘decision’ of the body or of the self, but that appearance is a misunderstanding.

Let’s look at four examples to see how that is so:

- The ‘decision’ to speed up the heart rate.

- The ‘decision’ to make a lane change while ‘driving’ a car.

- The ‘decision’ to use a tool to extract something from an inaccessible location.

- The ‘decision’ to support, or oppose, a genocide.

Most people will have no problem with the first example being completely conditioned. Our ‘selves’ are usually not even aware of it happening, though it requires a huge number of chemical messages, coordinated activities, and monitoring activities — numbering at least in the billions.

Similarly, it is pretty clear that the second example also requires no ‘conscious’ thought. We might well make the entire trip without even realizing ‘we’ have made many lane changes in the process. Or, in some cases, we might remember one or more lane changes, especially if they were challenging, suggesting we were ‘conscious’ of making them.

The third example is something many non-human creatures have been observed doing, and which we do all the time — such as when we ‘choose’ a knife or a spoon to extract that bit of peanut butter in the bottom edge of the jar. We probably think that we are exercising our ‘conscious’ minds to make that ‘choice’, though this, too, might be an autonomic ‘decision’.

The fourth example is one where we are probably quite sure that ‘we’ have made a ‘conscious’ decision, based on evidence and on the ‘conscious’ evaluation of that evidence.

So let’s go right to that fourth example to see what is really going on, and to see whether it’s substantively different from the first example.

The brain has a lot of modelling, information storage and processing power. It contains some 100 billion neurons (nerve cells), each of which is made up of 100 trillion atoms. Each neuron is directly connected to an average of 1,000 other neurons, with which it exchanges and relays chemical and electrical signals.

The human brain has evolved to create a model — a kind of map or representation consisting of ‘information’ in neurons — of the perceived ‘real’ world. The ‘content’ of that model is biologically and culturally conditioned. Depending on what we’ve been told by others (and what we’ve ‘learned’ by reading) the model is populated with ‘information’. It is also populated (probably uniquely in humans) with assessments and judgements about the ‘meaning’ of that information. These, too, are strictly the result of biological and cultural conditioning. So if a human body witnesses someone hurting another, the assessment will often be that that behaviour is ‘wrong’, and that the observer ‘should’ intervene. So what’s happening here?

The model is ‘telling’ the body to do something. What does the body do? It (or more precisely all the creatures that comprise it) does exactly what it’s been conditioned to do. It will intervene, or not, regardless of what its model tells it it ‘should’ do. The model only comes into play after the action has been taken.

In the circumstances in example four above, our conditioning will determine whether ‘we’ argue with someone about the genocide, and whether we will take action in support of or in protest of the genocide. Only then, after that action, will the model be used to assess (judge) that action (or inaction).

But surely, you might say, we ‘learn’ from the model, and that learning will inform future decisions. But no, we don’t. The process by which our beliefs and worldview (as reflected in the model) are conditioned, is independent of the process by which our actions are conditioned, as shown in the chart above. Our beliefs do not ‘inform’ our actions — That’s perhaps why we are sometimes ‘upset with ourselves’ for what we have done or not done compared to what we (the model) think ‘should’ have been done. Our actions ‘inform’ our beliefs and worldview, but only after-the-fact, and it’s strictly a one-way process.

So what, then, is the purpose of having this complex and energy-consuming model if it has absolutely no effect on ‘our’ behaviours (ie the apparent collective behaviours of the trillions of creatures that comprise ‘our’ bodies)? Excellent question! There would appear to be no more purpose of having and ‘maintaining’ the model than there is having an appendix (though even the appendix might, it is now thought, have some residual if inessential purpose). There is evidence that non-human creatures, and early humans, had and have no such model ‘guiding’ them, and have thrived perfectly well without it. And there are humans who assert that they have entirely ‘lost’ their sense of self and separation from everything else, and that it’s obvious the ‘self’ is illusory and completely unnecessary.

Then, if it’s useless, why did this model evolve? We can’t possibly know. Nature appears to try out mutations and new features in evolution, just to see if they make creatures more ‘fit’. So maybe the capacity to develop and maintain this ‘model’ of reality, our arrogantly-named ‘consciousness’ (which should properly be called self-consciousness ie the construction of a model of reality in the brain with the idea of a ‘self’ in it) was just tried out for no other reason than that it could be tried out — ie that there was ‘room’ in the brain for it.

So, getting back to our fourth example and how it differs from the first: What we think of as ‘our’ ‘conscious’ ‘decision’ is neither conscious nor a decision, nor is it even ‘ours’. The only thing that distinguishes what we think of as ‘our conscious decision’ from ‘decisions’ our bodies make autonomically like regulating our heartbeat, is that the parts of our brain that has constructed a model to represent reality has used that model to rationalize the supposed ‘decision’ after the fact. And even that rationalization is just the chemical processes of billions of tiny creatures sending ‘signals’ back and forth, exactly as they have been conditioned to do.

That is all that ‘consciousness’ is — the neurons in the brain reflecting on how what was apparently done ‘fits’ with the model that was constructed. ‘Our’ ‘consciousness’ has no effect on ‘our’ body’s apparent behaviour whatsoever. It just ‘accounts’ for it, ‘makes sense’ of it.

Imagine it as a frenzied accountant with a green eyeshade that grabs all the receipts and cheque stubs flying around the office and dutifully processes them into a (very incomplete) set of financial statements that purport to ‘represent’ or ‘model’ the business. The business is of course much, much more than the records in the accounting model of it, including the ‘bottom line’ judgement of how well it’s doing, but don’t dare say that to the accountant! And especially don’t tell the accountant that the business seems to be operating just fine without any accounting needed at all. (Yes, I know, the metaphor has its limits — but it’s kind of fun, especially since that’s how I made my living for many years.)

So here ‘I’ am, toothbrush in hand, staring into the mirror, not quite yet fully ‘reconstructed’ and awake. What am I looking at, exactly? And who, exactly, is doing the looking?

I was struck by Robert Sapolsky’s admission that, despite having concluded with near-certainty, based on all the available science, that we humans have no free will, he has no choice but to continue to behave and think about the world, almost all of the time, as if he did have free will. That is, after all, how he has been conditioned his whole life. He cannot do otherwise.

And this is what I think about as I look in the mirror. I know this body I see is not a coherent, individual, centrally ‘controlled’ thing, but I can’t help seeing it that way; that’s how I’ve been conditioned. And I know that there is no real ‘self’ here, inside this body somewhere, looking in the mirror; that’s just the brain’s concoction to try to make sense of the electro-chemical signals reaching it. But I’ve been conditioned to believe this self is real (it certainly feels that way, and everyone around me will readily assert that, yes, each human has a real self). So I see a self, imprisoned in and responsible for this body, when I ‘know’ that is not the case.

This hand now apparently spreads the toothpaste on the toothbrush and raises the brush to this mouth. The thought arises: “Did I remember to put the kettle on?”. A laugh begins, but where does it begin?:

Fifteen facial muscles contract and stimulation of the zygomatic major muscle (the main lifting mechanism of your upper lip) occurs. Meanwhile, the respiratory system is upset by the epiglottis half-closing the larynx, so that air intake occurs irregularly, making you gasp. In extreme circumstances, the tear ducts are activated, so that while the mouth is opening and closing and the struggle for oxygen intake continues, the face becomes moist and often red (or purple). The noises that usually accompany this bizarre behavior range from sedate giggles to boisterous guffaws.

The laugh produces a spray of toothpaste on the mirror. This hand rushes to clean it off, even as I continue laughing ‘helplessly’. The entire body has taken part in this strange activity, unwitnessed by ‘other people’. Many muscles, signals and chemicals were involved in this extraordinarily complex activity.

‘I’ had nothing to do with it. But the model in this brain immediately goes to work to ‘make sense’ of it. “All kinds of animals laugh, according to science”, I read, on my phone. But apparently only humans laugh at themselves. (And, no, the mirror doesn’t count.) Now there’s even more laughter. Who’s laughing now?

‘I’ look back into the mirror, and wonder: What just apparently happened? And I know, somehow, that ‘I’ will never know.

Enjoyed.

Fantastic post Dave and appropriately “I” apparently read it having apparently woken at 4am for no bloody apparent reason!

It looks like we are finally coming to grips with “consciousness”. Researchers such as Iris Berent are probably on the right track.

I was always sceptical about theories such as IIT and claims that one can measure degrees of consciousness. IIT claims that everything in the universe is conscious and could even be measured (Phi) ! It is incredible that such nonsense could pass as the leading scientific theory of consciousness.

Self-consciousness is most likely the result of evolutionary exploration of available spaces for better survival in some species.

Humans, as evolutionary constructs, can only hope that evolution can further smooth some of the rough edges of being self-conscious. It would be nice if feelings of sadness, unhappines, a. o. could be softened

somewhat. But evolution doesn’t give a hoot about the feelings of the creatures it brings into being. All that counts is whether it works better in the survival and procreation game. So, don’t put your expectations to high.

Excellent.