This is #30 in a series of month-end reflections on the state of the world, and other things that come to mind, as I walk, hike, and explore in my local community.

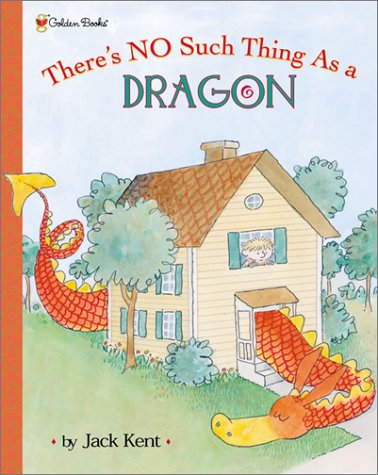

a children’s book about the dangers of ignoring a problem until it grows to be unmanageable

“Toward the end of his book Why We Remember, Ranganath expands his focus from the individual to examine the social aspect of memory. He cites a startling analysis of casual conversation which found that forty per cent of the time we spend talking to one another is taken up with storytelling of some kind. Whether spilling our entire past or just quickly catching up, we are essentially engaged in exchanging memories. It should come as no surprise that communication renders our memories even more fungible. ‘The very act of sharing our past experiences can significantly change what we remember and the meaning we derive from it,’ Ranganath writes, and distortions multiply with each telling…”

— review of neuroscientist Charon Ranganath’s book Why We Remember, in the New Yorker

The weather is lousy — “June-uary” has arrived early in Vancouver this year and we’re back to wintery rain and wind. So I’m just wandering in the neighbourhood. Today I’ve decided to listen for stories, but just to hear the narrative — not trying to decipher what the story “means” or why the speaker is trying to tell it.

In reading the book review quoted above, I was surprised that the percentage of casual conversation taken up by stories was as low as 40%. I would have guessed closer to 90% — what else, after all, do we have to say to each other? We tell stories, I would say, mostly for the same reason I blog — to try to make sense of things by ‘talking out loud’. So I’m out here, walking and listening, collecting my own data.

We naturally change the story — “what we remember and the meaning we derive from it” — for that very reason: so that it makes more sense. So that it fits better with our collective beliefs and worldview about what is, what was, and why. No matter that the story is ‘no longer’ true — it never was true; it is by definition a fiction. And because, as I’ve written often of late, we can’t help ourselves when it comes to story-telling; our conditioning from childhood is to create a belief system (a worldview) and to use stories selectively as scaffolding to support it.

So perhaps not surprisingly, the first story I hear as I’m walking comes from a little girl walking and talking with her mother; they are just emerging from a take-out shop. The part I hear is:

“… and then the dragon jumped up on the chair and grabbed the Cheerios box and ate all the Cheerios…”

I have no idea whether this story is the girl’s invention, or whether she is retelling the plot of a cartoon or a book or a commercial. But it doesn’t matter. This story is just as credible and just as true as the story her mother will later tell others about the service in the take-out shop. There is no such thing as a dragon. It’s all just stories.

Since I’ve started writing and musing upon the illusion of self and its relationship to the real world, I’ve started to see two superimposed “worlds” everywhere I go. There is what I’ve been conditioned to call and appreciate as the “real world”, with real people with real selves making decisions about what they (their bodies) will do, and making judgements about what they see and hear and read.

And then there’s this other world, comprising staggeringly complex and astounding complicities of trillions of cells doing only and precisely what they have been conditioned to do, appearing collectively as ‘individual’ bodies. In this other world there are no ‘selves’ in control of those bodies, and the bodies’ apparent actions are ‘simply’ the aggregate of the conditioned behaviours of these trillions of cells. In this other world the ‘self’ is just an invention of the brain — a story. To try to make sense of things. To no effect, and for no necessary reason.

…..

A man and a woman (she has an umbrella; he is very wet) pass me on the sidewalk, talking and moving at a considerable clip. I speed up slightly to hear their conversation. The woman says:

“… He didn’t apologize in the least! Can you imagine anyone treating their employees that way? So that left me no choice but to quit…”

And then the two worlds’ versions of the couple turn the corner out of hearing range. In one, a distressed woman tells a story about what she’d decided to do. In the other, each of trillions of cells do the only thing their biological and cultural conditioning could have done, given the (apparently unfortunate) circumstances of the moment, and the result is the appearance of a woman making a decision and then telling a story about it.

And none of the stories, in either ‘world’, is ‘true’. A ‘true’ story is an oxymoron. It’s all just trying to make sense of things that cannot possibly be made sense of, and which don’t need to be made sense of. But our conditioning is to try to make sense of everything, and to re-tell our stories until they at least ‘fit’ our worldview a little better.

Beyond the astonishing complicity of these trillions of cells doing what they must, stories are, I would suggest, all ‘we’ are — the content and processing of the beliefs (including beliefs about what has happened and why) and the worldviews, together comprising the little model of reality concocted in our brains, with the idea of ‘us’ at the model’s centre.

And we relate (etym.: “to bring back”) these stories because that is how human selves ‘relate’ to other apparent selves — how we compare and align the little model of reality in ‘our’ brain with others’.

Wild creatures, it seems, are able to ‘relate’ to each other just fine without the need for stories. Or selves.

…..

As I walk along the rain-drenched street, and then through the nearby mall, I take note of fragments of other (unconnected) conversations I hear, and muse upon the stories they imply:

[drawing a baby dress from a shopping bag] “Isn’t this adorable? I think it should fit.”

“All he had to do was ask me.”

“She said she was going, but I bet she flakes out.”

“I can’t, man — Everyone would know it was me.”

“I’ve tried. The doctor’s advice didn’t help at all.”

“Yeah, the visit was amazing. We both want to go back.”

“Someone should just tell her.”

I’m trying really hard not to flesh out these fragments into stories, but it’s almost impossible. This is what we’re conditioned to do. Everything that’s said that isn’t already a story has to be made into one; that’s how we ‘make sense’ of it. “And then what happened?” — Each of the fragments of conversation above could be a ‘prompt’ for a creative writing class.

I keep walking, paying attention to the attempts of the conversants I pass to ‘relate’, in both senses of the word. It seems to me that their body language and facial expressions and tone of voice are ‘relating’ a lot more information, and helping them ‘relate’ to each other much better, than the clumsily-formed, imprecise, easily-misconstrued words they are using. But it’s not as if we have any choice.

…..

A few moments later, back outside again, I near a young couple who are, improbably, sitting on a very wet bench; the rain has mostly abated. They are talking in urgent, animated voices, and as I pass by, he changes his voice to a kind of growly whisper, leans over towards her, and says:

“Are you kidding me? He’s just trying to get inside your pants!”

She scowls quickly at him, looking around to see who might have heard, and I hurry by, looking straight ahead as if I heard nothing.

The young lady does indeed have very nice pants. I stifle a laugh. I am determined to not try to make sense of these conversations, to not try to judge or imply meaning to what is being said. They’re just stories, after all. I could invent explanations of jealousy or protectiveness on the young man’s part, but those would just be stories too. The young couple (ie the complicities comprising their apparent bodies) are just acting out ‘their’ conditioning. No other words or actions were possible.

I resist the temptation to imagine a story of what they will be doing later — stretching the story out into the future as well as back into the past, to root it in meaning. Without the notion of time (which some theoretical physicists now say is also a fiction), we couldn’t tell stories at all.

Just as with the woman who now has to find a new job, I’m pulling for the young couple on the bench, and the woman with the baby dress, and all the other complicities of creatures comprising the bodies of apparent individual people attached to the stories that arise from the conversation fragments above, to have their stories have happy endings.

We all want to know, of every story: How’s it Going to End?

…..

The rain has started up again, and I duck into my favourite café to escape it. Two older men have settled into the comfortable stuffed chairs in the corner, and they are talking rather more loudly than most patrons of the restaurant do. (Though they are white males, after all.)

I order my latte and take up a seat not too far away. I smile at the fact that adult men seemingly tend to talk to each other, rather than with each other. Unlike some older males whose conversations I’ve heard here, their conversation is not about their pasts — either what has happened to them recently, or what happened long ago (recounted either ruefully or nostalgically). Instead, it’s more like a back-and-forth volley of anxieties about the future. Over the next few minutes they relate their unease about the world’s political situation, the economic situation, climate change, their work situation and, to a guarded extent, about their personal health and financial situations.

That could be me saying that, I say to myself as I listen. I can ‘relate’ to that.

Stories about the future are very different from stories about the past. The former require conjecture and imagination, while the latter are largely straightforward and unarguable. As the men talk, the information that underlies their anxieties is presented, as are their opinions on these situations, but the stories — how they might imagine things playing out, best or worst scenarios — are unspoken. Are they thinking about these stories and just not sharing them aloud? Or can they not imagine, or do they dare not try to imagine? I cannot guess.

This is, I suppose, how they’ve been conditioned to talk. Their conditioned ‘adult male’ conversation lacks candid expressions of emotion (other than annoyance and mild anger), and lacks reassurances from either of them that their concerns are either overstated or well-justified.

They are, it seems to me, talking out their anxieties about the future to get some sense in their own minds about whether these anxieties are warranted, and why. It’s like they’re conversing with themselves, rather than each other, and just sharing a table and coffee to do so.

And then one of the men says:

“Sometimes life’s like a hamster wheel; you never figure out how you got on it, and there’s no way to get off it.”

I smile. There’s surely a whole bunch of stories embedded in this ‘depersonalized’ statement. If it’s an invitation to explore what’s behind it, it’s lost on the other man. There is silence, and then the other man changes the subject.

…..

As I walk home, it occurs to me that so much of what we say in our conversations with others (and perhaps in our ‘inner’ conversations with ourselves as well) are rationalizations for feelings we don’t quite understand or aren’t quite comfortable with. Maybe that’s why so many attempts to ‘relate’ to others seem to be searches for reassurance. “Tell me that I’m not crazy to be feeling and thinking this.”

And the other thing that occurs to me, reviewing the fragments of conversation I’ve heard today, and their implied stories, is that, either obviously or latently almost all of the stories that we ‘relate’ to each other have dragons in them. A “baddie”. Something a bit scary, or stressful, or worrisome, or unknown (“Dramatic tension and conflict is essential to a good story”). Or something longed for. Or something misunderstood. Or something unresolved (“How’s it going to end?”) .

Even though, as we all know, there is no such thing as a dragon.

Unless there Really is such a thing as a Dragon, and all our musings are attempts to avoid the realization that we are continually avoiding to Actually See what is so abundant apparent even to small children, whose insistence in Reality is overshadowed by our Fear to acknowledge what is everywhere Seen and

avoided.

Dave, I usually just read your posts in the email but wanted to chime in on your site to let you know there might be a bunch of us out here enjoying your writing but not being counted as visitors. Thank you for continuing to share your story.

Thank you, Joy and Jim.