THIS IS PODCAST #2 (28:10) — CLICK ON THIS ARCHIVE.ORG LINK TO LISTEN TO IT. TRANSCRIPT FOLLOWS.

DAVE: As a result of my first podcast, with Chris Corrigan a couple of weeks ago, I decided to explore the issue of leadership, and specifically whether we need leaders at all. The natural choice for podcast #2 was therefore Jon Husband, author of the Wirearchy blog, which proposes that we move to (and suggests we are already moving to) a new method of social organization, driven by social networks and our desire to make our institutions democratic, instead of power and authority.

Our modern systems in affluent nations are largely hierarchical. Our political systems subordinate the individual and the community to the state, and have us leaving all important political and social decisions to political ‘leaders’ who are presumed to know better than we do what is needed, and how to ‘govern’ the body politic. Even our votes for these so-called leaders have become inconsequential in modern political systems whose ‘leaders’ are largely removed from contact with or responsibility for individuals and communities. The issues are dumbed down for public consumption, and political leaders act in their own self-interest, not in ours. Grassroots movements, most recently the failed MoveOn attempt to reassert control over the irresponsible power hierarchy that controls the US political system, are as close as we’ve come to introducing wirearchy into the political arena.

It is much the same story in the business community. The modern corporate structure is inherently hierarchical and anti-democratic — there is no one-man, one-vote in the boardroom. The ‘leaders’ of big corporations are over-rewarded and revered for successes that were the work of the front lines or the result of good fortune, and are fired or chastised for failures that are similarly not their fault. Such is the cult of leadership and the adoration of hierarchy in the corporate world, which, with the advent of globalization, is now ubiquitous. Cooperatives and progressive entrepreneurs in what I have called Natural Enterprises must unlearn all the mythology of hierarchy as the only way to make a living, in order to create new, flat, sustainable organizations that are responsive and responsible to all.

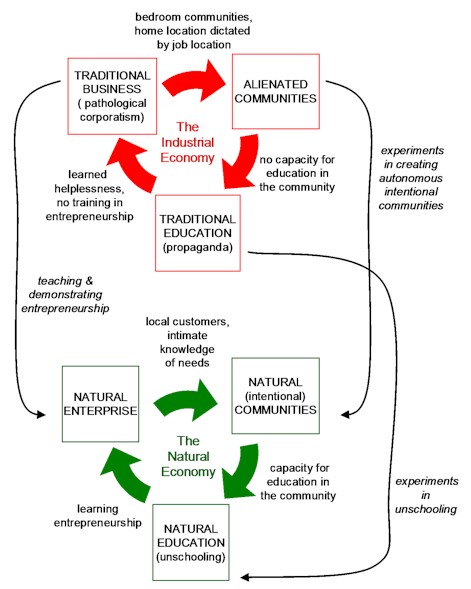

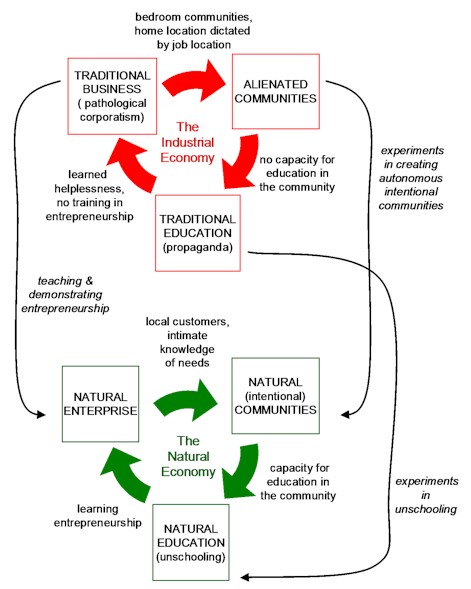

And it’s also the same story in our education systems. As in business and in society, students are ranked into hierarchies, told what to do, and told their ‘place’ in the hierarchy. Failure to strive to raise one’s rank in the hierarchy is considered a fatal character weakness. Those who unschool or home-school their children are considered eccentric, and admonished that they are making it more difficult for their children to ‘fit in’ with modern society. As I’ve written on my blog, the hierarchies of our educational, business and political systems reinforce each other and create a vicious cycle. We are taught that there is only one way to learn, one way to make a living, and one way to live. We are taught to know our place. We are taught to be, as cummings said, ‘everybody else’.

So in my Skype conversation with Jon, I started by asking him whether he felt that hierarchy was embedded in our DNA, and inherently the way social structures tend to evolve, or if he believed, as I do, that hierarchy is unnatural, and that our unhappiness with it and its dysfunctionality are a result of trying to make people think, act and behave in unnatural ways.

(I caution listeners that the audio quality of this recording is not very good, as I reached Jon in a cafˆ©. It does get a little better as the conversation proceeds)

JON: Many people suggest there is hierarchy everywhere in nature, that it’s a natural way of ordering things — that is embedded in our modern culture and it underlies Taylorism, the division of labour and the way work and society is structured, the way we assign and accept roles. It’s quite useful for assigning responsibility and accountability to people for human activities and decision-making. Humans have also used at least symbolic hierarchy, even prior to the modern age, for honouring elders, assigning culpability for wrong-doing, and so on.

Hierarchy is an aid to decision-making. It underlies the whole apparatus and rule of law in our society. In the legal system, judges are the ultimate symbols of hierarchy. They’re elevated to the position where they have the responsibility and authority to make judgements on human affairs.

I don’t think hierarchy is either bad or good. It has acquired something of a reputation in the last 20 years in the notion of command and control, because of the many bad decisions that that notion has engendered. But I would argue that that’s an artifact of organizational structures and the notion of traditional hierarchy in organizations which have been supplemented and distorted by organization designs, compensation structures etc. and hence become problematic. For example Lew Gerstner in his book from the mid-90s about the turnaround at IBM, with well-paid and senior people in IBM delegating upwards, and using hierarchy as a crutch.

DAVE: I asked Jon whether he thought this was inherent human social nature, whether we are inherently hierarchical creatures, or whether this is something that is acquired, learned.

JON: I have a sense that it is not a fundamental aspect of humans; though it is used in past and current societies it is not inherent in the functioning of groups or purposeful activity.

(We went on to chat about intentional communities, and specifically about how expanded Asian immigrant families are probably the most successful intentional ‘communities’ we have — they work together, often crowded into one house, create and run a family enterprise together, and acquire additional property as their work permits. Other than this, we tend in affluent nations to think of intentional community as an anachronism, a relic of the hippie communes of the 1960s and 1970s. We concluded, I think, that we can’t seem to operate politically without someone in charge of the important decisions.)

DAVE: In my last year of high school, a group of us were permitted to work independently and not attend any classes provided we kept our test grades up. Rather than working ‘independently’ we chose to teach each other, to learn collectively, and to learn as much as possible outside the confines of the school. It was a spectacularly successful experiment, as our group won most of the scholarships and increased our grades substantially, but it was never repeated, apparently because it was considered ‘elitist’. Several of us had trouble in university readapting to the expectation we would sit in classes taking notes from droning professors.

Jon told me about his self-directed learning experience at Glendon College in Toronto.

JON: I was asked not to come to class. The deal was I wrote a paper and was graded on that, and throughout my four years I just continued that way. I got very good grades. I would credit that with the fact that now later in life as a result I study and work harder and this is something many people can and do do, reflecting that ubiquitous self-learning impulse; the way of bring this forth and evoking it are incredibly important. John Taylor Gatto’s work shows that industrialists who formed corporations designed school systems to resemble and mimic the hierarchy, standardized curricula, testing and performance management schemes in business. I’m not sure which came first, whether it was the grading systems that led to performance management schemes in work or the other way around. The potential to change that dynamic is there and many people are beginning to act on it. Homeschooling and the horizontal links on the Web are examples of this adding new dimensions to the ways we learn.. This is also reflected in the work of Wim Veen at the University of Delft, his work on Homo Zappiens about how individuals learn, and the implications for school structures and their teaching and learning processes.

Most of the learning we do is in social interactions; that’s also how we develop character, as what we talk about and how we act is mirrored and reflected by others, and that is how we come to understand and know things.

DAVE: I asked Jon: If we learn how to learn without hierarchy, by teaching each other, by doing instead of being told what to do, could it change everything? Could this change in how we learn bring about a change to how we live (our social and political systems) and how we make a living (our economic and business systems)?

JON: I think conceptually that possibility is there. What is perhaps insurmountable is the notion of purpose and how that is married into the service of capitalism. People working in non-hierarchic ways would have to work together in very different ways from the way we do in the capitalist system that is driven by competition and the notion of self-interest, wherein people do things because they want to get things and have more. That’s the dominant structure in North America and Western Europe today and it’s antithetical to the purpose of intentional community, which is to feed and look after each other’s wellbeing and other things that are much less consumer oriented.

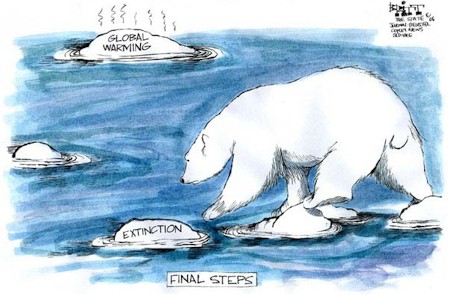

To get there, even if we had many people self-learning it would take a large and persistent social movement to change the capitalist system so that people would begin to come together in self-managed and self-governed and self-directed teams and ways. We may be forced to it by a calamitous environmental disaster. It’s possible, but there are large obstacles.

DAVE: I told Jon it sounded to me as if he was a skeptic of Bucky Fuller’s argument that it’s foolish to try to change existing systems, that you have instead to create new ones from scratch that make the old, dysfunctional systems obsolete.

JON: I am a skeptic because I believe the dominant system has been made tighter and tighter so building something new will be a formidable challenge and will be resisted every step of the way. Planned, large scale organizational change has often been attempted, but substantive change only really occurs when there is a ‘burning platform’, when there is no alternative. I like Bucky Fuller’s thinking, and that of other change advocates like David Korten, Barbara Marx Hubbard, Alvin Toffler, but we’re arguably no further along in realizing these visions than we were 20 years ago.

I think it reflects the notions of leadership at all levels, including servant leadership. I don’t think we’ll get away soon from job evaluation methodology which is at the core of the gestalt in many organizations. Nobody really talks about this. I don’t see people in established organizations being willing to let go of the different levels and different pay grades — a lot of this is bound up with the notions of power and status and ego. The pressures for servant leadership and large-scale engagement are growing, so I hope we will see people beginning to explore alternative organizational design methodologies and practices, because once alternatives have been shown to work they will be adopted. WL Gore may be an example, but it’s dated — it’s been held up as the example for 20 years now, and we need more examples that have been shown to work before we’ll evolve models that work for today’s conditions. I think wikis, blogs, social software and Enterprise 2.0 concepts hold a lot of promise, especially among the new digital natives in the workplace. So to that extent my hope continues to spring eternal.

We’ve watched the evolution social computing and social software of blogs and wikis for five and a half years and I think the names for these tools have hurt them and held back acceptance in business. Because they don’t understand them those in business say they don’t have time to do it, but I think they don’t have time not to do it. I see this becoming the main medium for doing knowledge work, probably supplanting or at least complementing e-mail. It’s all about sharing knowledge and constructing meaning in the context of a given project, socially. These tools make it easy to do that, so I see in ten years these becoming ubiquitous worktools. And that will help address the things we’ve just been discussing to be realized.

DAVE: Finally, I asked Jon what he would suggest our listeners read if they want to know more about servant leadership and the other concepts he’d been talking about.

JON: Robert Greenleaf’s work on servant leadership, Jim Collins’ Level 5 Leadership, Peter Block’s Stewardship (which is the book that made me quit my high-profile, highly-paid consulting career), Patricia Pitcher’s Artists, Craftsmen and Technocrats: the Dreams, Illusions and Realities of Leadership, and Susan Wright and Carol MacKinnon’s Leadership Alchemy are the ones that come to mind.

DAVE: After leaving Jon to his latte in the noisy cafˆ©, I reviewed the resources he had suggested and thought about his answer to the question Do we need leaders? I guess I was surprised that Jon, who has been such a fierce opponent of manipulative, incompetent, bullying, overpaid and overrated leaders for so long, would seem to be saying Yes, we still need leaders, just a new type of leader. Humbler, more democratic, more inclusive, more consultative.

My answer remains an emphatic No. I don’t think people change, and in my experience leaders in politics, in society, in business and in educational systems do, on balance, far more harm than good. Worse, their very presence give us an excuse for inaction, for not taking personal responsibility, for not knowing about and not dealing with issues that need action to be taken by all of us. The natural way to live, I believe, is in community, where all decision-making authority and responsibility are devolved to the collective of the community, arrived at by a combination of consensus and the taking of personal responsibility.

The natural way to make a living, I believe, is in a completely equal partnership with people you love, in community, where all decision-making authority and responsibility are in the hands of the partners, arrived at by a combination of consensus and the taking of personal responsibility.

And the natural way to learn, I believe, is self-managed and life-long, by watching others and doing, practicing, the things one needs to learn to make sense of the world, to live a healthy life, to make a living, to live in community with collective responsibility for the others in the community, and to acquire the sense of personal responsibility needed to do what has to be done to make the community, and the world, a better place to live.

[Postscript: Jon’s offline rebuttal to my conclusion:

The only thing I might quibble with is your conclusion, my “Yes, we still need leaders … ” What I was trying to say, but did not clearly enough, is that en masse we do not yet “know” well enough, in a wide enough range of areas, that we can operate effectively without leaders. Our education, socialization and the structures into which we are jettisoned after “schooling” actively work against that awareness, and leave little or no room for practicing … so people have to go through very disruptive processes at some point in their lives if and as they grow disillusioned with the ways they are led and governed, to begin to lead themselves and become (much) more capable of living, loving and working differently, in conditions where self-organization becomes available and attractive. It demands a new and different set of responsibilities from each individual, of which she and he have to be actively aware and desirous of enacting and embodying.

So there’s a process of unlearning and re-learning that involves throwing over or off much or most of what we “know” … Yes, I put scare quotes around “know” here and above for a clear reason. I believe many, if not most people want to get there, once they begin to realize there’s a “there” there.]

|

I‘ve been learning a lot in the past couple of weeks. This learning has all come from conversations, not from reading or research. And to my surprise, none of these conversations has been face-to-face or even voice-to-voice. From these conversations, all with good friends, I have learned three important lessons.

I‘ve been learning a lot in the past couple of weeks. This learning has all come from conversations, not from reading or research. And to my surprise, none of these conversations has been face-to-face or even voice-to-voice. From these conversations, all with good friends, I have learned three important lessons.