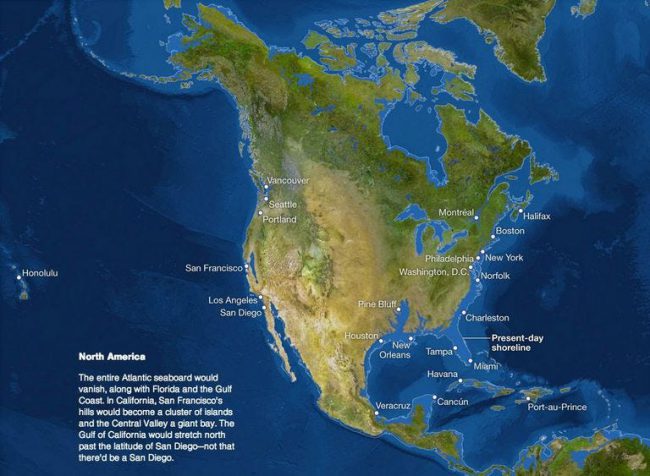

This is #18 in a series of month-end reflections on the state of the world, and other things that come to mind, as I walk and hike in my local community.

image by Midjourney; not my prompt

This body that I presume to inhabit likes to eat outside. So this month, it’s taking me to cafés with outside dining. I’ve volunteered to do some recycling work (mostly sorting bottles and cans to be shipped to recyclers) for a non-profit on Bowen Island, where I lived for twelve years.

So I board the SkyTrain from my new home in Coquitlam, in the NE corner of greater Vancouver, to make the long but quite comfortable trek to Bowen, in the NW corner of the metropolis. A trek between two places with very different cultures. At least, that’s what I’d always thought.

I’m fascinated by human cultures, and especially by what seems an almost zealous willingness of many people to stereotype and differentiate other cultures from our own. Perhaps we identify our culture by how it differs from others’. So I’ve tried to learn about what it’s like to live in faraway countries with ostensibly very different cultures, ideally by talking to people from those countries, but also from articles and stories written by natives and ex-pats. What I’ve found most interesting lately have been YouTube videos by people talking about and showing us their home towns and how they live. Like this one showing life in Tehran, and Elina Bakunova’s videos about her home country Russia, and the day-in-the-life videos by Daniel Dumbrill taken across China. These posts are neither sponsored by state propaganda agencies, nor by anti-government hate-mongers seeking a pretext for war. The picture they paint is a balanced one, of lives that have the same ordinary modern ups and downs we pretty much all deal with. Their lives are so much like ours in so many ways. Why do we keep forgetting that?

As I board the ferry, I recall a time several years ago in downtown Vancouver, when I was looking for a place to get something copied or faxed, and was directed to a place that was down a flight of stairs from street level. I found myself in a completely different world — a role-playing/gaming room (I later learned it was a PC Bang) jammed full of big screens and fast-CPU computers, with all of the signage in Korean, and a concession that served only Korean foods. One floor above were expensive, exclusive Robson Street shops with almost entirely Anglo-European customers and staff.

From that experience, I had derived this perception of supposedly multicultural Vancouver as actually being a collection of unconnected bubbles, ‘communities’ using the same public infrastructure but living almost entirely separate lives. The great diversity of Vancouver’s people, it seemed, was visible, but their actual cultures were not.

So now I look around the Bowen Island ferry and all I see, as usual on that ferry, are white faces, after I’ve just come from my new home community where fully half of the population is what in Canada are called “visible minorities”. (In the case of Coquitlam, they are largely Chinese-, Korean-, and Iranian-Canadians, based on how they self-identify on their census forms and the principal language they speak at home.)

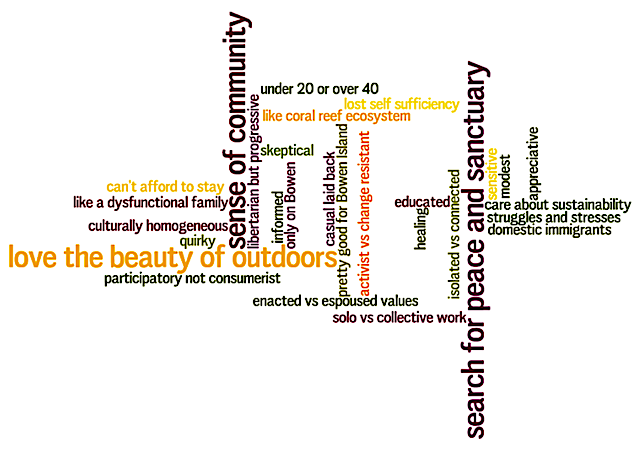

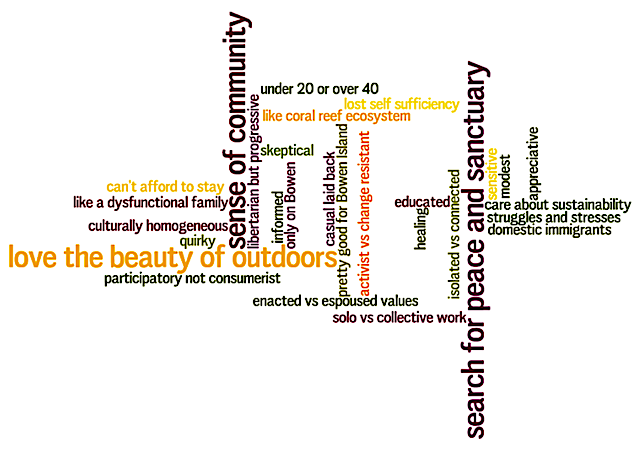

Back when I lived on Bowen, I became the principal researcher and author of an award-winning Arts & Cultural Plan for the island. In it, we tried to capture the essence of the island’s culture in this wordle:

A search for beauty, community, and sanctuary were the words we heard most often when we interviewed Bowen Islanders about “our” culture. And culturally homogeneous.

Yet, as I walk off the ferry, it dawns on me that the islanders I lived among for twelve years were not, and are not, a particularly happy lot. Studies repeatedly show there is a high level of substance abuse, mental health problems, and financial anxiety on the island, and Bowen’s social media (and café conversations) reveal a high level of distrust of ‘mainlanders’, of governments of all stripes, and internally among the residents, who are often angrily politically divided and prone to internecine scapegoating and public humiliation. (You know, all the stuff that social media excels at.)

These are, I think, people with reluctantly hardened hearts. That’s what happens, perhaps, when you keep moving west in search of a better way to live, or a better community to live in, and finally run out of places further west to go, but never really find what you were looking for.

As much as islanders talk of community, and band together in opposition to things they oppose (‘developed’ parks, taxes, logging, growth, camping, off-road vehicles, regulations of any kind, and ‘excessive’ tourists, notably), there is nothing cohesive that really makes them a community. Perhaps that’s why, when I had to leave, it was logistically challenging but not at all heart-breaking.

In the Cultural Plan, we defined culture as a community’s shared beliefs, behaviours and aspirations (and we defined arts as the expressions of that culture). But what does it mean if you have neither a real, cohesive community nor an identifiable, connecting, healthy culture? Can you even have one without the other?

These are the questions I think about as I walk up from the ferry to the recycling depot. On the way up, three people I hadn’t seen in years recognize me, call me over to their cars by name, and offer me a ride to my destination (even though two of them are actually headed in the opposite direction). This is what a community does, right?

Well, maybe. In our very brief conversations before they drive on, they all tell me about some local issue (the ferries, the proposed campground, tourists) they are unhappy about. What kind of community is only held together by what they are collectively opposed to? How durable is a culture that is relentlessly critical and endlessly aspirational, rather than celebratory, joyful and grateful?

That’s not to criticize the fine people of Bowen, of which I counted myself one, and expected to remain for the rest of my life. We are the result of our conditioning, and, perhaps as a result of that, the nature of many Bowen Islanders I met was very often dissatisfied, quick to assign blame, and hoping for a better future but not very optimistic about it. I can relate — I was the same for most of my life. I suspect this is probably a defence mechanism after (in my case, anyway) decades of disappointment and failure to meet other people’s often-unreasonable expectations. But it is not a terribly endearing human quality, and not a very solid cement with which to build culture and community.

At any rate, during my recycling shift I am regaled with anecdotes about the continuing turnover of Bowen residents, and about the many people I know who have recently left or are planning to leave, most of them involuntarily (there are no affordable rental accommodations, and few rentals available at any price).

After my shift, I get a ride down to the ferry terminal, and settle in at a local café to await some friends I’d arranged to meet with. As I wait, two women with white canes navigate their way to the next table. I am struck by their joy and wit as they talk with each other. One of the women is talking on the phone, and relates to the caller that she’s only been blind for a month as a result of complications from “otherwise-successful” heart surgery. She’s laughing and cursing like a sailor and making jokes about her situation. Her friend is giggling, and flirting with the server. In five minutes I hear enough good material to launch a comedy series.

After my meetup with friends, I make my way back to the ferry.

When I am back to Coquitlam I go to another café. Here, I see and hear a lot of different cultures. I hear Farsi, Korean and Mandarin being spoken at different tables, but the conversations don’t intersect. At the few tables where more than one ethnicity is evident, they are speaking in English, and I smile at how much louder the English conversations are than those in other languages. These cultures all have cafés, markets, and similar public meeting spaces as essential elements of their social lives, but this café is an amalgam of cultures, not a mixing pot.

And although these “hyphenated-Canadian” cultures are very different, they have one very endearing quality in common, and that is politeness almost to a fault. They greet strangers unfailingly in elevators, say “excuse me” and “thank you” and “I’m sorry” even more than most Canadians, and they smile and meet your gaze when they pass. This is done, by all but the youngest, as a simple act of respect and accommodation. It seems a conscious act, a learned and practiced behaviour. Formal, perhaps, but not just as a formality.

At least, I think it is. As I sit in the café people-watching, I realize I know almost nothing about any of these “hyphenated” cultures, which I appreciate are modestly different from the non-expat cultures, which have a different context, a different set of milieux, and different neighbouring cultures, all of which inevitably affect behaviours, beliefs and aspirations. Iranian-Canadian culture, I think, is inevitably neither Iranian nor Canadian, but something distinct and apart from either.

If I were to try to create a wordle for any of these cultures, I wouldn’t even know where to start. On the one hand, Coquitlam prides itself on being clean, modern, safe, and welcoming to an extraordinary number of new residents. On the other hand, social life here is largely determined by traditions, language, and food preferences, and so it is somewhat insular and family-based, more than in many places. And the daily commute of so many means that Coquitlam is very much a “bedroom community”, so there is less time for discovering your neighbours and involving yourself in community activities.

Having said that, I am aware of some similarities among them, which are not in themselves remarkable but quite distinct from Anglo-American cultures. For a start, invitations to visit someone’s home are evidently serious matters, where the host will often offer a fairly lavish set of options for food and drink, even if it’s just an invitation to tea. Secondly, it is apparently normal for guests to bring a small gift for the host as thanks for the invitation. And thirdly, dressing up seems to be an important aspect of just about every social activity, even a visit to the mall or grocery store. I feel seriously under-dressed in the café, now that I’ve noticed this.

The excessive and skyrocketing cost of housing (both owned and rented) means that many of Coquitlam’s residents are living in smaller apartments increasingly farther-out. It is not unusual for me to see, from my ‘terrace in the sky’, parents in nearby buildings putting multiple kids to bed in what are clearly one-bedroom apartments. We do what we have to do.

Combined with that, I often hear that many “new Canadians” have come here expecting to contribute to the growth and success of Canada’s professional, technical and managerial sectors, only to find out that their qualifications are not recognized here. So we have the tragic paradox of a shortage of skilled workers in medicine, engineering and other fields, while many highly-qualified immigrants are stuck doing menial jobs.

On the ferry, then the bus and then the SkyTrain, I watch the changing profile of faces entering and leaving. I wonder at the accommodation, the patience, and the equanimity of the people in my new neighbourhood — it must be very stressful and frustrating dealing with the discrimination, the work bureaucracy, the lack of affordable homes, and the cultural ambiguity and unfamiliarity of their new community. And the vast majority of them are very highly educated, well travelled and knowledgeable about the world, comfortable in multiple languages, and were highly-respected in their former communities. Yet I almost never see or even hear acts of anger, violence, or despair. Of course, that doesn’t mean it’s not there.

And this makes me realize that despite my curiosity I still know next to nothing about these cultures, about these people, my neighbours. I have been in the homes of new Canadians since moving here exactly twice. And when I look in the faces of so many, I have no idea what they’re thinking and feeling, or even how I would start to find out. I am especially curious about the feelings of the school-kids, both new immigrants and second-generation Canadians.

So I do the usual online searches — statistical data, personal anecdotes, blog stories, films, even AI queries. I learn that Iranians come to Canada for business opportunities, personal security, political reasons, and to offer better opportunities for their children. They fly back to visit Iran often, but rarely return there permanently.

By contrast, Koreans come to Canada because of Korea’s very high levels of financial inequality and unemployment, and they fly back to Korea less frequently, but once they’ve retired, often return to live out their lives in Korea, even when that means leaving the now-adult children they brought over or raised here in Canada.

Still, I’m impatient to learn more, and finally hit on the idea of looking for videos about the inter-cultural dating scene, hoping I can glean something about new Coquitlamites, and perhaps especially about how our young people from various cultures feel living here.

I hit paydirt with a series of six videos that, unexpectedly, feature fun ‘dates’ between a young Korean singer and vlogger, and a young Iranian actress/model who has moved to Korea to get more work. (Part 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.) The videos are falling-down funny and charming and they’re a gorgeous couple, so they’re great for unwinding, as well as getting something of a sense for what it’s like to be a young Korean or Iranian. And just like when I watched the videos about life in Iran, Russia and China, I came away with the overwhelming sense that, at least in today’s generation, those cultures have become as atomized and culturally disrupted and homogenized as Anglo-American cultures. This series could in fact have been portraying a young dating couple just about anywhere on the planet. Same preferences. Same objectives in a date. Same beliefs and behaviours and aspirations. Same culture? Or no culture?

Does that mean the whole idea of diverse cultures, and the whole idea of true community, has been or is being lost? In future, will our idea of cultural affinity and connection be nothing more powerful than what sports team we root for? What is left of a society that has no communities, just individuals, like inert atoms that never combine into molecules, never become more than the sum of their separate parts? Is such a society ‘cultureless’?

. . . . .

Back at home, I’m up on the roof watching the newly-fledged young crows testing their wings. They’re learning to ride the air currents between the apartment towers, and clearly having a blast doing it. Two of them in particular seem to be mimicking the seagulls, flying un-crow-like distances without flapping their wings, as if daring each other to see who can glide the furthest. One of them, comically, lifts one wing too soon, and does what is clearly an unintended barrel-roll in midair, before righting itself and soaring gorgeously around the building opposite mine and then dipping under and rising up above and ahead of the other crow. They’re as fun to watch as the dating couple videos. But a very different culture.

Or maybe not. I recall on the return ferry seeing one tween-ager goading another to steal six packets of sugar from the ferry cafeteria without being caught. (This is an ongoing battle on the ferry. At one point all the condiments were removed from the area and customers had to ask the cashier for them.) Is this the analogue of the young crows’ bravado?

I kinda hope not. If it is, it’s a big come-down from the fire-jumping at the Iranian festival of Nowruz. And even from the Korean PC Bang Internet Cafés with their dazzling competitions. Yeah, I know, “Kids these days…” Totally conditioned. Just like us.

. . . . .

There are “one world” idealists who believe social homogenization and the obliteration of separate cultures will reduce divisiveness, competitiveness, xenophobia, and wars. I think that’s a neoliberal fantasy. Diversity, I think, is essential to learning and understanding how the world works, and also essential to innovation, resilience and even identity. Magic happens at intersections.

Much of the world seems to have lost, or perhaps never had, a true sense of community. If we also lose our cultures, how will we cope with the looming economic, political, ecological and social collapse our world is now facing?

If we have nothing in common with our fellow humans except our inescapable predicament, what exactly are we left with?

This body seems to be trying to persuade me that I think too much, and pay attention too little. It wants me to just watch, and wonder, and stop asking what it all means, and what ‘should’ be done. It’s probably right. It’s telling me to close the computer and go outside in the sun. There’s a new little café just a block away…

It’s a chilly, rainy day here in Vancouver, the kind of day that makes you pensive, wistful, melancholy and all those other feelings that are mostly sad, but are also, often, thoughtful and creative. It’s almost as if the rain gets inside you and lubricates the memory, the emotions, and the imagination.

It’s a chilly, rainy day here in Vancouver, the kind of day that makes you pensive, wistful, melancholy and all those other feelings that are mostly sad, but are also, often, thoughtful and creative. It’s almost as if the rain gets inside you and lubricates the memory, the emotions, and the imagination.

W

W