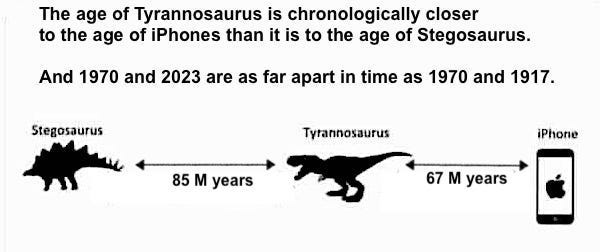

This is #14 in a series of month-end reflections on the state of the world, and other things that come to mind, as I walk and hike in my local community.

I am walking toward the city’s small sports stadium, which, except in those rare times when an event is in progress, is open for use by the public, and is a place for practice.

In the elevator, on the way down from my apartment, I meet a woman accompanied by a small, anxious-looking dog wrapped in a winter coat. When I ask the woman about the dog, she looks rather apologetic and says:

“Oh, it’s not my dog, really. Her owner, my friend and neighbour, is now bedridden and not able to take her for walks. It’s the least I can do. Poor dog is 17 years old, and deaf and blind now, but once she’s navigated out the elevator she’s in her element, and she loves to sniff everything outside. When she dies, I don’t know what my friend is going to do. The two of them are inseparable. She has a little ramp to get up onto the bed, and spends almost all her time curled up with her person, sleeping and getting pets. They have a love that I don’t think many people could ever understand.”

She’s tearing up a bit, and so am I. Just another small grace, these walks, these stories, happening all around us that we never learn about. I wave to the dog-walker and head north.

I think about the famous commencement speech by David Foster-Wallace, about how so much depends on how and what we pay attention to. He said:

“Learning how to think really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think. It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience… [long, funny, grim story about having to do ghastly, infuriating grocery shopping at the end of a mind-numbing day at work].

“The thing is that, of course, there are totally different ways to think about these kinds of situations. In this traffic, all these vehicles stopped and idling in my way, it’s not impossible that some of these people in SUV’s have been in horrible auto accidents in the past, and now find driving so terrifying that their therapist has all but ordered them to get a huge, heavy SUV so they can feel safe enough to drive. Or that the Hummer that just cut me off is maybe being driven by a father whose little child is hurt or sick in the seat next to him, and he’s trying to get this kid to the hospital, and he’s in a bigger, more legitimate hurry than I am: it is actually I who am in his way…

“Most days, if you’re aware enough to give yourself a choice, you can choose to look differently at this fat, dead-eyed, over-made-up lady who just screamed at her kid in the checkout line. Maybe she’s not usually like this. Maybe she’s been up three straight nights holding the hand of a husband who is dying of bone cancer. Or maybe this very lady is the low-wage clerk at the motor vehicle department, who just yesterday helped your spouse resolve a horrific, infuriating, red-tape problem through some small act of bureaucratic kindness.

“Of course, none of this is likely, but it’s also not impossible. It just depends what you want to consider. If you’re automatically sure that you know what reality is, and you are operating on your default setting, then you, like me, probably won’t consider possibilities that aren’t annoying and miserable. But if you really learn how to pay attention, then you will know there are other options. It will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow, consumer-hell type situation as not only meaningful, but sacred, on fire with the same force that made the stars: love, fellowship, the mystical oneness of all things deep down.”

I arrive at the little stadium, having made my way past the many numbered sports fields, mostly occupied now by practicing girls’ teams, since it’s not “prime time” for boys’ practices and games. I maneuver onto the eight-lane track through the runners and walkers, and begin my daily half-hour jog. I smile at the metaphor of all these people, going around and around in circles, getting nowhere. When the weather’s bad, I do my run on the gym’s treadmill instead, where it’s the belt that goes in circles.

There’s a slightly-overweight boy walking mid-way between the lanes marked for running and those marked for walking. As he comes up behind a bevy of chattering girls roughly his age jogging slowly on the outermost of the ‘running’ lanes, he slides over into the innermost lane, puffs himself up, and sprints past them. I laugh. I’ve seen him before, and, as I expected, as soon as he’s around the curve from the girls, he swings back into the walking lanes, gasping.

I think about the crow outside my window who regularly drops a pebble in midair and then dives down to grab it in his beak, only to soar up and repeat the exercise over and over. Showing off to potential mates, or just practicing? Or just doing it for the sheer fun of it? Unlike the gasping boy on the track, the crow need not invent a story of what might be possible if he plays his cards right, and says the right words to the right girl at the right moment.

There is an older couple ambling, hand in hand, along the walking lanes of the track. She keeps shooing him on ahead, saying, in some universal language: “Go on now; you don’t have to wait for me. I am only slowing you down.” But he refuses; of course, she is not slowing him down. They are like two cars on the same train, hitched. Without her, he would quickly go ‘off the rails’. At least that is my story. Does she know this, I wonder? And does he know how to tell her?

Unlike Mr Foster-Wallace, I don’t believe we have any control or choice over what or how we think, or what we notice. Our conditioning determines what we think and notice and do, and whether we are or are not self-aware enough and motivated enough to see or think about things differently. We may be conditioned to see others compassionately, believing that we’re all doing our best, and, as the famous quote in the photo above puts it, exercise the kindness that comes from understanding humans’ endless, tragic and ubiquitous struggles.

Or we may be conditioned to become inured to caring about others, because it’s just too much sadness and sorrow to bear, and because trying to care when we can’t, paralyzes us into despair, callousness and indifference.

Both kinds of conditioning are perfectly understandable. No argument, no intervention, can make someone care when they can’t.

After a year of gentle rehab, I have finally recovered the ability to run, for an extended period, without pain or exhaustion. I don’t know why this is such an important capacity to me, such a core part of my self’s identity, but it is. Perhaps I still believe I am no use to the world broken.

As I run, I watch the practice going on in the field in the centre of the track. It’s a girls’ field lacrosse practice, with a sizeable group of young teens for such a male-dominated sport. Unlike the boys’ game, and like ice hockey, women’s lacrosse is non-contact, and as such it’s a joy to watch — faster, more elegant and more strategic than the body-damaging, penalty-ridden, more discontinuous men’s game.

I am astonished by the intensity of the practice, the concentration and obvious care that goes into their repetition and learning of moves. This is serious play, and a commitment to the kind of rigorous, patient practice that makes so much of a difference in so many fields of human endeavour.

Practice, it seems, is a bit out of fashion these days. In the workplace, it’s now become too expensive (ie too profit-suppressing) to provide time and space to let people learn, and make mistakes, on the job, so we expect their schooling to give workers all the practice they need to be competent, or perhaps extraordinary. But they don’t get it in the educational system either.

For most, I fear, developing competence in human endeavours, from gardening to parenting and from coding to business and political governance, is now a matter of fake-it-’til-you-make-it, and if you fail, well, try the same approach in some other field. Perhaps as a result, there is a huge, and unnecessary, amount of failure, that ultimately costs us more than the investment in practice up-front would cost. But we no longer dare think that far ahead. Why practice when the world is fucked?

We shouldn’t be surprised, then, that in writing, in music, in diplomacy, in the media, and in business “management” we are now surrounded by hacks, dilettantes and incompetents who believe their diploma or their ‘natural gift’ gives them everything they need to be brilliant, without the need for practice.

Practice is, after all, tedious and exhausting. If it’s done badly, it will merely reinforce errors and bad habits. It can be discouraging. But it is essential. The lack of practice in so many aspects of our society shows up in the mediocrity of our art, music and literature, the utter incompetence of most organizational and political ‘leaders’, and the lack of innovation in technology and the sciences.

I shake my head and extract myself from this rant-inside-my-head, and simply admire the intensity and perseverance of the young lacrosse players. They remind me of the skateboarders that I see every place where there is a ramp or a curb or an unimpeded stretch of concrete. They show us that practice is ultimately its own reward, and that sometimes, despite everything, people will be conditioned to be willing to practice, and practice, and practice — until they can do, easily, what they once thought impossible.

I just hope that these young lacrosse players will be spared from the epidemic of abuse, psychopathy, hazing, debilitating injury, and cheating that has ruined most ‘professional’ and many amateur sports and destroyed so many young bodies and young lives.

Walking home, now, beneath the overhead skytrain tracks, I come upon a guy sitting at a concrete table in the midst of the wide walkway. He has his bicycle upside down on the ground beside him, much of it dismantled, and there are dozens of parts organized neatly on the table where he’s working with a cloth and a small toolkit. He is singing, and smiles at me as I pass. I have no doubt that he will soon have reassembled all these mysterious parts into a precisely engineered whole, and will zip by me before I get home.

I think back to last weekend’s Bowen Island Fix-it Fair, where my friend Paola Qualizza and her husband organized a dozen volunteer repairers of electronics, musical instruments, bicycles, clothing and furniture to spend three hours fixing close to a hundred odd items that the islanders brought in. Many of the fixers took home items they didn’t get around to fixing in the allotted time. Several people came in, toolboxes and sewing machines in hand, just to help the fixers, impromptu. Others came in, empty-handed, just to watch and ask questions and learn how to fix things themselves.

We’ve been doing this, twice a year, for nearly a decade, and it keeps growing. I just sat at the entrance, smiling and greeting people as they came in, and marvelling.

Mid-way through the event, a young man carrying a baby in a soft (“SSC”) carrier took the baby into the men’s washroom, drew down the baby change table, and quickly and skilfully changed the baby, chatting away to it the entire time.

A few minutes later, I saw a teenaged boy, with his apparently-repaired skateboard under his arm, stride out of the school gym where the event was held. His black hoodie, in large letters, read: “Be gentle, man!”

It’s a magical event.

So now I’ve made it home. The Amazon delivery guy is struggling at the front door of the apartment building, dragging a full mega-bag of parcels, each to be delivered to the recipient’s door. I hold the door open for him, since his load is too awkward and heavy to haul to the door before the 5-second opening click ends. I thank him for doing his thankless, ghastly job. As I watch him juggle several devices and plan out his delivery, I realize that he, too, is learning to be really good at what he does, through practice. There was no manual that taught him to be so competent.

Beneath the hardened exteriors of so many of the people we meet, there are endless stories of grief, of shame, of sorrow, of fear and anxiety and helpless rage and hopelessness and struggle. Mostly we dare not tell them, or even hear them. We cannot reveal ourselves to be that vulnerable to the rest of us eight billion mildly deranged monkeys, all of us pacing our cages and wondering what the next uncertain day will bring.

Yet the world is full of small graces, when our absurdly busy lives and relentless conditioning let us take the time to notice them.

Back in my apartment, I make a cup of tea, and look out the window in the falling dark. I nod and quietly thank those whose many small actions of kindness and compassion are never noticed, and those whose unrecognized, practiced competence makes our world a slightly better place, and its monkeys a tiny bit less deranged.