Malcolm Gladwell loves wading into complex and controversial subjects. In the November 8 New Yorker he writes an article called Getting Over It, on the subject of surviving trauma. He uses the success of the protagonist in the 1955 novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit to survive a double trauma, and the failure of the protagonist in the 1994 novel In the Lake of the Woods to cope with a very similar trauma, to advance his thesis that in the past half-century there has been Malcolm Gladwell loves wading into complex and controversial subjects. In the November 8 New Yorker he writes an article called Getting Over It, on the subject of surviving trauma. He uses the success of the protagonist in the 1955 novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit to survive a double trauma, and the failure of the protagonist in the 1994 novel In the Lake of the Woods to cope with a very similar trauma, to advance his thesis that in the past half-century there has been

…a shift in perception so profound that the US Congress could be presented with evidence of the unexpected strength and resilience of the human spirit and reject it without a single dissenting vote.

The evidence he refers to is a study in the Psychological Bulletin of long-term effects of childhood sexual abuse that concluded that, in the large majority of cases, unless it was extreme, very frequent, or accompanied by physical abuse or prolonged neglect, the long-term effect was so small as to be barely statistically significant. The report was so offensive to so many that Congress was pressured to repudiate it, and did. My readers know I don’t place much stock in psychology, and that I prefer explanations for behaviour that are rooted in real science, or at least Darwinian principles: Actions and behaviours that increase a species’ capability to survive will be selected for, i.e. a propensity to exhibit such actions and behaviours will become more and more prevalent in the population. I’ve argued before that depression in today’s world may be natural. I’ve also argued that when we are unhappy or grief-stricken we create stories that provide us with solace, so that our vivid imaginings can become so real that they become alternatives out of time, even to the point where ‘what might have been’ becomes to us a regrettable real possibility in the present. This prevents us from seeing this alternative reality as false, achieving closure, and moving on with our lives. We are all living our own stories, and there is no way to see them objectively as real or unreal, true or imaginary. To us, they are absolutely true. When we suffer trauma, we may put it behind us, wrap up that chapter in our story, or we may not. When that trauma is compound — a physical and sexual and mental trauma, or one that combines actions (like abuse) and inaction to address it (like neglect or passive complicity by others), or one that is chronic or frequent, there is little doubt that it is harder to get past. In nature, a fight or flight instinct kicks in when danger threatens. Most animals in nature face death and witness death often in their lives. They escape, perhaps watching as a mate or community member or child is eaten by a predator. In any case the event is traumatic — adrenaline surges, the body goes into overdrive, some shocking event occurs or doesn’t, and the survivors are left to deal with the result. If the response of a species were to grieve for years over the loss, or over a decision error that may have cost a loved one their life, the species would not survive — it would be incapacitated. In a balanced ecosystem, these traumatic events are regular but not chronic — most species spend most of their time in the joyous activities of eating, exploring, mating, playing, sleeping, and sensing the world around them. Their failure to grieve, at least for long, is in my opinion due not to their small brains but to the fact that there is too much joy and wonder in the world to waste much time grieving over what happened or might have happened. It’s Darwinian — it happens that way because it works, it optimizes the healthy survival of the species. As Jeffrey Masson has shown, animals with larger brains tend to grieve longer, and return to their grief over a longer period, probably because they have better memories that are triggered by sensations that remind the creature of the traumatic event. Elephants weep each time they return to the site where a loved one lost their life, for their entire lives. That is natural, but not debilitating. The grief, the trauma, does not consume them to the point where they are incapacitated by it. Only humans kill for revenge. Only humans kill large numbers of their own. Such behaviour is, on the surface, anti-Darwinian — it hurts the species rather than helping it to survive and perpetuate it. Misery is anti-Darwinian — those that live in physical or emotional misery tend to withdraw from social activities, fail to defend themselves from predators, die young from stress-related activities, and, if they’re female, become infertile. This is nature’s extreme-stress safety valve. Such misery is the consequence of over-crowding, too many competing for too few resources. As Edward Hall explains, in such circumstances (very rare before the advent of civilization) adrenaline is used to quickly thin the crowd and restore the balance with the rest of the ecosystem. The world we live in today is horrendously overcrowded, insanely out of balance with the rest of the ecosystem, and our evolved intelligence is allowing us, at least physically for a short time, to offset all of nature’s attempts to reduce our numbers to sustainable levels. Nature evolves new diseases that exploit crowded concentrations of one species, we reply by inventing antibiotics and antiviruses. Nature drives up our levels of adrenaline to levels that provoke war, anti-social behaviour, massive depression, and we reply with technologies that sedate us or cheer us up, that imprison those who can least suppress their violent urges, and which refocus our adrenaline on activities that do not kill. But nature always bats last in this competition of wills. I would argue that we all live, now, in a state of continuous agitation and constant anxiety, massive stress that has resulted in us all becoming mentally ill. Our whole lives are an incessant trauma — work stress, competitive stress, stress to have ‘enough stuff’, stress to be accepted by others. Our desire to find a way to try to sustain a society that is so obviously unsustainable, and to deny the damage we are doing, to ignore the massive misery that prevails in our world, to believe against overwhelming evidence that we can somehow innovate ourselves out of the horrendous mess we have created, is evidence of utter, adrenaline-crazed insanity. We are only happy in those brief delusional moments when the awareness of the utter horror that civilization has wrought is temporarily suppressed — by constant education of denial of that reality, by drugs, by sexual distraction, by media that suppress the truth, by hiding the worst atrocities behind closed doors and walls where we can try to pretend they aren’t happening. Today, we are all struggling to survive a life-long trauma, and it is interesting to me that in the last half-century our literature and our political leaders have become much more pessimistic about our ability to do so. It is almost as if, by proclaiming that most victims of post-traumatic stress disorder and childhood sexual abuse cannot be expected to get over those traumas without enormous help and intervention from our society, we are saying to ourselves three things:

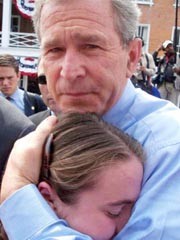

This is tricky ground, but I think there is a lot of mass psychopathy going on here. Alternative explanations welcome, as always. The photo above aired as the focus of a commercial for Bush in the last few days of the election campaign. I think it is brilliant, an absolute coup against all the negative advertising that dominated the campaign. It was actually taken by the girl’s father at a Bush rally. The girl’s mother was one of the victims of 9/11, killed in the attack on the twin towers. The girl is a survivor of trauma, and the impulsive hug from Bush on learning of her story is captured in the photo. It’s the only time I have seen Bush without a mask. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

I agree strongly with this (can one agree more or less strongly ?;-)But nature always bats last in this competition of wills. I would argue that we all live, now, in a state of continuous agitation and constant anxiety, massive stress that has resulted in us all becoming mentally ill. Our whole lives are an incessant trauma — work stress, competitive stress, stress to have ‘enough stuff’, stress to be accepted by othersMe being me, and usually somewhat contrary, I have argued from time to time that all of the projections of people living longer lives will be countered to some significant degree by all the cognitive stress, anxiety and general existential pathology we are all experiencing. It’s as if at some level we all “know” this is not the right or most effective way to live.In the immortal words of Leonard Cohen, whom I quote too often these days … “Everybody Knows … everybody knows the boat is leaking, everybody knows the captain lied” and so on …We are all living in ongoing trauma .. the only times it is maybe possible to escape is when we walk or spend time deep in nature, but even there all too often we are confronted with the scars of we humans’ traumatic effects on nature … which then traumatizes some of us even the next little bit more.

Dave: Thanks for this very thought-provoking post which makes a lot of sense to me.

Interesting thoughts. Did you read the studies that showed that the brains of victims of childhood abuse developed differently than non-abused people? This is the scariest thing I’ve ever read, and suggests I can never be the same person as the little child I was before I was abused (mentally and physically). Secondly, have you known someone who was the victim of childhood sexual abuse? I do, and they it was clear to me that they were screwed up beyond belief by it. Perhaps their entire lives will be spent in one way or another dealing with the aftermath of those horrendous acts. The depression and suicide attempts spoke volumes about the lasting impact. So I don’t quite go along with the thesis that sexual abuse is not as bad as society makes it out to be. leo

Leo: I think the situation you describe (where it is sexual combined with other forms of physical or psychological abuse, and repeated or constant) is the exception that Gladwell acknowledges. I’ve known people who were badly abused repeatedly or chronically, and others who were badly neglected (and I’ve read about the ‘wild child’ cases) and in all of these the trauma *was* engrained, severe and permanent. But I also know people who suffered only occasional childhood sexual or physical abuse, often under non-coercive circumstances (e.g. sexual contact initiated by a childhood friend rather than someone with power, or occasional bullying), and those people show no signs of permanent damage — or at least not of damage any worse than the rest of the population exhibits.

A true response to abuse is to say NO, and choose a different reality that does not include the abuser. Most victums find it very difficult to get to this point(internally) and the abuse continues. When you can say NO the abuser loses his power over you and you can(if you survive) go on with making your own life.Courage is essential.

Avi: Agree completely. The problem is that usually the abuser has power and authority over the victim, so it becomes very hard, even dangerous, to say no. It’s especially difficult when the victim is a child. We’ve been brought up, most of us, to be cautious in resisting bullying in case resistence inflames even more violence. But passivity can also embolden. Even more important than courage, I think, is knowing where and how to reach out for help. In Canada we are inundated on the media with public service ads that tell victims where to call for help, but on the US media I rarely see such ads. And I’ve never seen them where I would expect to see them most — during kids’ shows.

For those that don’t have access to the print version of the article Dave cites, it’s available online.