Modern Western education teaches us collectively, and then kicks us out to beg for a job where we will work, for the most part, individually. No wonder this crazy system, which gets it exactly backwards, is so inefficient and dysfunctional. What if we were to invent an intelligent system, one which recognized that we learn in unique and individual ways. What would it look like? In an earlier article, I described the cognitive experts’ theory of how we learn: We take in information through our senses, at least when we’re paying attention. Then we process this information through our personal mental models or ‘frames’, coded right into the neurons of our brains, kicking out any concepts that don’t fit the frames and any references we don’t understand. Next, we store the filtered, processed, regurgitated, parsed ‘learnings’ in our ‘working memory’, the brain’s RAM, where they continue to be molded, considered, and amended until we have essentially ‘decided what they mean’. Then they get filed away in long-term memory, to be accessed and extracted if and when they are ever needed again, or forgotten if they are not. Picture a teacher in a classroom telling 20 students about, say, monarch butteflies. Because the learning process is so individual, the twenty students will end up with twenty very different conceptions of what the relevant information is and what it means. If you don’t believe me, debrief with a bunch of people who have just attended a presentation — you’ll be astounded at the different perceptions you’ll hear. The best way to convey information is to do it in a way that can be self-paced and immediately tested, by prompting participants to articulate the learnings in ways that make sense to them, to challenge and discuss them, and to apply them in a useful context. Telling stories also helps the learner to grasp the concepts in more concrete and memorable terms. Good teachers, of course, try to compensate both for the lack of context in the sterile classroom (using visual aids) and the differences in the way we internalize information (by discussion and exercises), but teaching-by-telling, in a classroom, is a hopelessly dysfunctional way to impart both information and skills. There is a reason why ‘on the job’ training has such an excellent reputation. It provides an immediate context that makes learning easier. It provides an immediate chance to practice or apply what has been learned. And it provides one-on-one coaching for the many aspects of learning that may require iterative reinforcement, and a chance to ask questions. It’s especially valuable when what is to be learned is a skill, not information.

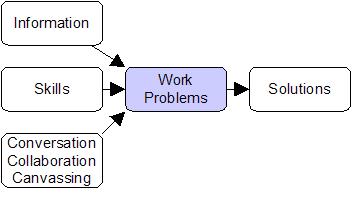

The map above was developed by reviewing a variety of school, university and applied curricula, and considering how they might be applied in three different contexts: making a living, deciding where and with whom to make a life, and gardening. It lists six main fields of information about the world that would provide useful knowledge to do this work, eight core skills that would be useful to apply to this work, and two sets of applied skills or competencies that integrate the eight core skills. How might these be crafted into a curriculum without ‘teachers’ and without walls, a curriculum that could replace the boring and impractical curricula that are taught in most schools and universities today? The best way to explain this is to describe a day in the life of a ‘student’ in, say, her late teens. Let’s suppose our student, Kim, is looking to be a musician, a writer, or a veterinarian. How might she acquire the 16 critical learnings in the above map, in a way that also integrates the technical learnings of music, language and medicine she needs for her chosen work? Our success, and the quality of the solutions we come up with, is a function of the quality of these three inputs, and our ability to apply them effectively. For Kim, the problems, the context we want her to use to learn and practice applying knowledge and skills, is that of her three chosen fields of endeavor, music, language and medicine. So suppose one of the information modules that Kim has to complete (part of the third field of information, The Economic System) is The History of Agriculture, with Richard Manning’s Against the Grain as a suggested reading. It might be paired up with the second of the core skills, Critical Thinking. And suppose the chosen application for these learnings is Animal Nutrition, related to Kim’s interest in veterinary medicine. So her assignment for the next two days is to do the History of Agriculture reading, and the self-study on Critical Thinking, to call on the people in her self-compiled Animal Nutrition resource list (which would include other people also studying Animal Nutrition, and some veterinarians, and some experts, and some potential customers, people with animals), and to bring all of that information, skills, and people help to bear to address some specific assigned problems in Animal Nutrition. From those people, and in applying what she’s learned, Kim also picks up what she needs to know of the technical learnings of veterinary medicine. See how this could work? It meets all of the criteria in the pink coloured box above. It entails no scheduled classes and requires no bricks-and-mortar buildings. Integrated, contextual learning. And what’s the chance Kim’s going to be bored doing this? Let’s try a couple more examples. From the sixth field of information (Arts, Science & Technology) the information module is Acoustics, paired up with the fourth of the core skills Attention Skills: Making ‘Sense’ of the World (learning to listen not only to music but to bird songs and train whistles), and the chosen application is Composing Harmony. The resources could include scientists, musicians, musicologists, experts in meditation, engineers in recording studios, and, of course, other students of music. Or, from the fifth field of information (Human Nature) the information module is Negotiation & Conflict Resolution, paired up with the sixth (Collaboration & Collective Wisdom) and eighth (Story-Telling) core skills, and the chosen application is Writing About Making Love Last. The resources could include negotiators, teaming consultants, James Surowiecki, Thomas King, Tom Robbins and other successful writers, and other student writers. This approach turns education on its head, and centres it on the student instead of the teacher and on learning instead of teaching. There would be no need for what we now call ‘teachers’ with this system. Instead, we would need learning facilitators, and personalized curriculum developers to organize and coordinate the resources (information, self-directed learning materials, lists of people to talk to, and appropriate ‘pairing’ of the information modules, the core skills and competencies, and the people in the community who can provide context in which to learn them). Kind of like bibliographers, connectors and coaches rolled into one. Giving each student a personalized ‘map’ of what to learn and where to find the resources, and then leaving them to their own resources to go out into the great wide world and learn. That’s my model for education. To me it seems inclusive, flexible, engaging, and yet eminently practical. It is participatory, both in the way it requires students to practice what they’re learning, and in its outreach to the community. And with the money we would save on school buildings and administrators we might even be able to pay Messrs Manning, Surowiecki, King, Robbins and millions of other writers, doctors, musicians, teachers and experts to spend some of their time mentoring the next generation. Or is my vision clouded by my own mental models, my own instinctive and perhaps naive belief that motivated young people will learn on their own, their own way, and need only a gentle framework and some occasional coaching from someone who will listen to them, instead if teaching them, in order to make a living for themselves and those they love, joyously, in our brave new world? |

This is exactly the approach used by the Sudbury Valley Model Schools – <http://www.sudval.org/>. They also use democratic approaches that look very similar to Wisdom of the Crowd principles. What I most appreciate is how SVM breaks free from the conservative stereotypes about how children must be controlled since they won’t try to learn on their own and will become dangerous gangsta hoodlums. John Taylor Gatto’s book “The Underground History of American Education” may be heavy handed, but the thesis of the book is crack-on: schools are social engineering labs with the sole purpose of spitting out compliant, conservative corporate consumers. If there is anything that we can take an active approach and make immediate changes to help fix our world, supporting schools that are similar to SVM, Montessori, etc. will break the corporatist hold on our children.

Dave,BTW, this is exactly what I was thinking when we were corresponding about a “Natural School”.

Forgot to post the link to Gatto’s book: http://www.johntaylorgatto.com/chapters/

FYI, I like the MindMap stuff for providing a quick glance at your thoughts. My current Bliki choice is http://snipsnap.org which comes with a built-in graphing (MindMap, Organigram, etc), however, it’s very static and updates to complex graphs are difficult. I’ve found an excellent Java applet that “balances” nodes in a logarithmic fashion so that you can see the entire network of nodes, with the most important nodes (the selected nodes and it’s nearest neighbors) being the largest. The applet also allows click-through. Imagine a bliki that uses this applet as a way to navigate the site. I’d like to tie snipsnap with the applet to allow quick and easy bliki reorganization and navigation. The next step would be to tie bliki, applet, ontology, and sem web things all together as a personal knowledge management platform.

Graphing applet: http://hypergraph.sourceforge.net

Well, on the one hand, I spent quite a bit of time in HS & College taking “classes” where I was DOING not sitting. Computer programming lab, applied physics lab (making integrated circuits), yearbook, video production, ceramics, music, chemistry lab, drafting, auto-shop, welding, (on and on). Those “classes” were opportunities to put my hands in and do something, and so I’d hate to lose the buildings (and teachers) that provided those functions.As to the other functions (reading, writing, math, history, social studies, etc.) the big problem I see with alternate models for teaching those, is that almost every kid has no interest in those topics. I still to this day have managed to avoid learning *anything* about western civilization (call me a neanderthal). While there remains a gap between what the kids are interested in and what “higher learning” has determined is important; there’s going to be some coercion required to close the gap. And its a long (as in centuries) up-hill battle to reverse this, because these kids get their values from society (media, parents, figures of authority), and society just isn’t demonstrating that it values the learned mind.Finally, don’t look to the business world to help out providing learning environments for these apprentices. Until all the top down organizations of the world are toppled and replaced by natural enterprises, the focus is going to be on the bottom line, not on the human capitol that propels it. Businesses look at their employees as replaceable parts, not valuable assets to be invested in or even encouraged. Its a dire dysfunctional world out there.Ultimately, learning is not the school’s resposibility–its the parents. The school is just there to help.

Dale: Thanks for the on SVM schools. There’s one here in Toronto and I’ll definitely learn more. I’ve talked about Gatto before (he lives, in wilderness, not too far from here). The PKM platform idea sounds wonderful — I’m wondering if there’s some way we can make this ‘invisible’ and intuitive to users, so that blikis can be the mechanism for crossing the digital divide. The mindmap for this post was made with another sourceforge product, FreeMind, and it has the ability to capture hotlinks, graphics and other html in the nodes. Only drawback is that the reader needs to have the Freemind app or reader on his machine — the html is lost when you save the map as a jpg or other format.Derek: Labs are certainly better than classrooms, but why not have the students working in a real lab (R&D facility or commercial garage) instead of a ‘mock-up’? I also hated history in school, but that was because I couldn’t see the use of it — it was only later that I appreciated that the lessons of history are transferable. If I’d had the change to see the applicability of the lessons to today, and here, I think I’d have been engrossed. Just like everything else, I don’t think you coerce change, you just set up something that works better (like Dale’s SVM schools) and let the dysfunctional institutions crumble. And while I agree that big corps won’t want reams of students bugging their employees, I’ve been astonished to discover that NOT ONE entrepreneur I have spoken to has said he/she wouldn’t be delighted to show students what they do, let them kick the tires, answer Q&A etc.

Dave,Your model is wonderful in theory but seriously limited in applicability. A “cirriculum without ‘teachers’ and without walls” is a noble and worthwhile aspiration. The difficulty is in defining the real function of schools and education.Traditionally, schools have been a means of warehousing children not old enough for the industrial workforce. The secondary purpose has been to prepare them for entry into the workforce. It has never been to optimise them for entry.Dale’s example, the Sudbury Valley School, which meets many of the standards of your model, is an elite, and still considered experimental, school. I grew up in Sudbury, Massachusetts and knew a few kids that went there in the early days. It does warehousing with a very nice and engaging difference. It also costs over $5,400/year not including car fare.Th education given is no doubt superior to the mainstream. The students, however, are not, and never will be mainstream. They are privileged and always will be, barring catastrophy that is.My point is that we live in a world where models like yours are used to promote elites, not the mainstream and underclasses. The mainstream and underclasses are given some basic tools, some opportunities, and many lessons in boredom. Not because our schools don’t try to give them more. But because our public systems have never had the resources to give the kind of attention and sensitivity your model offers.It is unrealistic to think that warehousing of children will end. There are simply too many intractable reasons for it at all levels of class and privilege. The real emphasis of your efforts would more constuctively be to see how some of your ideas can be brought to excisting public education. You won’t get the ideal you want, but you can get some good results if you can find a way to drum up more resources.My concern is that public education is under assault and that your model might be used to drain and divert resources from public schools who at least teach the poor and middle classes some basic skill sets, and sometimes a little more. I’m concerned by your statement above that, “Just like everything else, I don’t think you coerce change, you just set up something that works better (like Dale’s SVM schools) and let the dysfunctional institutions crumble.”No Dave, in education, you look at the context of the situation, not the ideal. Then you try (as many have with varying results) to coerce the changes that you think will be most beneficial to the most. Let the least, the rich who send their kids to the Sudbury Valleys of the world, do what they do. If you try to go for the ideal without regard to the excisting struggle, everyone gets hurt.You’re squeezing the toothpaste from the top. Try workinging from the bottom.

With respect, Dave, I think you’re at once too optimistic (that the existing system can be fixed, rather than having to be replaced) and too pessimistic (that a model like SVM could never be scalable). SVM is elite and expensive now (though I’d bet $5,400 is less than what the public system costs per student per year, and really isn’t much money for something as important as education), but if it became mainstream I suspect it would actually be cheaper than the existing system. Yes, the existing system is a ‘warehouse’, but that’s because you have to imprison kids to get them to put up with it. If kids are motivated and given direction they’ll essentially look out for themselves and each other — they’ll be busy ‘working’ on their assignments and that will keep them focused, out of trouble, and safe, without the need for brick institutions (which don’t do that well keeping them out of trouble or safe anyway).

Dave,I simply ask that you look VERY CAREFULLY at the logistics of your model when applied to the vast majority of students. Could it realistically replace what we have now? If so, what problems or disfunctions would likely manifest? Could those problems be as bad or worse than what we have now?Most students today, do not have good non-autoritarian parenting and do not self regulate well. Most do not have parents who are willing and/or able to invest the time for proper oversight. Most have two working parents who are not particularly interested in humanistic matters or a liberal education. Most will, under your model, face learning guides that are, like staff members in our schools today, of mixed capacity and competancy. What about discipline and behavoral problems in students and teacher/guides? What about underprivileged students, like the hundreds of thousands we have now in the U.S., who come to school without even having had breakfast? How will all those problems be monitored and handled without walls?Most important, if we divert moneys to promote your model, will it really be cheaper, or will it bankrupt the excisting disfunctional system and set us on a path of possible total colapse?Sudbury Valley’s tuition is, I’m sure, subsidised in various ways, including endowments from alumni and families. What will the real costs be and how will they be accounted for? Your theory is fine, but what about practice?Sudbury Valley still has walls. Why? And people drive their children there everyday from all around the Eastern part of Massachusetts at considerable personal expense. I think your model has been in use at the college level for some time. I know Northestern has a good school to work program and UMass has its’ campuse without walls. Neither one has taken over as a primary practice though.Finally I want to say, I hope I’m doing what the comment section is meant for… asking hard questions.

> Labs are certainly better than classrooms, but why not have the students working in a real lab (R&D facility or commercial garage) instead of a ‘mock-up’?Here’s one point where reality takes a left turn from the plan. In Flagstaff (where I live), there are no “R&D facilities”. None. I’m sure there are some in Phoenix, which is 150 miles away.Here’s the key difference between a school and a business: in the school, the equipment is at my (the student’s) disposal. I can work on what I want. In business, the equipment is at the business owner’s and ultimately the customer’s disposal. If they want 1000 copies of a widget, as an employee, I’m sitting there day in and day out turning out those 1000 widgets, regardless of the educational value.

I think what Dave (Pratt) is saying (at least my take on it) is that trying to change *only* the educational system is not feasible because the rest of our social system is not set-up in a way that could handle the changes.I don’t think, judging from the rest of his blog, that Dave (Pollard) is suggesting that we try to change only the educational system and leave the rest of society the way it is now. Nor would anyone realistically suggest changing the social system and leaving the educational system the way it is now. The current educational system is only one part of the larger system, and all parts have to be changed more or less at the same time.BTW Dave, I’m glad you like the swans.

Dave Pratt,>>The difficulty is in defining the real function of schools and education.<>Dale’s example, the Sudbury Valley School, which meets many of the standards of your model, is an elite, and still considered experimental, school.<>Traditionally, schools have been a means of warehousing children not old enough for the industrial workforce. The secondary purpose has been to prepare them for entry into the workforce. It has never been to optimise them for entry.<>My point is that we live in a world where models like yours are used to promote elites, not the mainstream and underclasses.<>Most students today, do not have good non-autoritarian parenting and do not self regulate well.<>Most have two working parents who are not particularly interested in humanistic matters or a liberal education.<>Sudbury Valley still has walls. Why?<<True. However, many of the sVS model schools try to work around this. I believe that the walls are not for keeping the kids in, but for keeping mainstream society out to avoid the messed up things that people living in it will do. As for your implication about colleges not having walls, you should see the numbers regarding the incredibly high failure rate that institutionalized students have. They simply cannot cope with being set free from the walls. Home-schooled and other non-standard schooled children have much more success. However, a more important question we should be asking is: is college the right way?I have a very strong belief that the SVS model is a very good step toward creating a Natural Community. The very structure of day-to-day life there encourages democracy, self-motivation, and social responsibility.

Thanks, Dale. That is excellent advice. It’s interesting, you come across very differently here than on your own blog, stylewise, and differently again on the discussion forums. It’s like you show a different part of yourself in different online spaces — kinda interesting.

Aren’t we supposed to write to our audience ;-)My Artima blog is written in a journalistic/tech rag style because Artima is viewed as being very professional… part of the reason why some of the IT industry’s big hitters blog there. Another factor is that most IT people are seriously deficient when it comes to emotional awareness :-) I usually have a real struggle writing those articles because they’re so emotionally dry.I think the discussion forum differences might be partly due to “grazing” in the forums. I tend to see myself more as a facilitator to get people thinking. That approach allows me to subtly reveal my perspectives esp. in controversial subjects. In the forums, I don’t have a high level of trust and I want to lower my aggressiveness in my arguments just so that I can get people to listen. In fact, after a recent volley of messages where I became more direct, list activity dropped to almost nothing.Here, I sort of feel like I’m among friends. We have differences of opinion but we are otherwise supportive of one another.

I also have a very different in-person persona. My nickname (from college) is “bozomind” and most of my colleagues agree :-) I have a deep, unrestrained laugh that people either really love or really hate. I think that the people who don’t like my laugh is because I deliberately use humor to disarm people and reveal their truths to them.

We homeschool our young kids and we have, with another couple of dozen families, created a learning centre here on Bowen Island where our kids learn together for half the week, supplementing what they learn at home. It’s publically funded by the New Westminister school board at considerably cheaper than the cost of a public school. We have families in a variety of income brackets.Since we began a year and a hlaf ago (building on a foundational community that has worked together sine 2000) the community of parenst and kids have done some remarkable things not traditionally seen in “school communities.” Two full fledged business have started among the parents and a large number of us hire each other for spot work. Several creative collaborations have also evolved in the fields of perfomrance art and organizational development.If I had taken Dave Pratt’s advice, and the advice of others who see some redeeming qualities in the public system, I would be banging my head against the wall of “education reform” until my children were in university. Now I can just focus on their learning, and mine. I don’t begrudge people who send their kids to public schools – I’m all for choice – but we haven’t let a little thing like societal expectations stand in the way of creating a real multi-generational learning community.

It’s interesting to be accused of having “given in to societal expectations.” And then, to have someone proclaim their achievements beyond the norm, while presuming to fully know my position, or the quality or extent of my “advice.”I certainly had no intention of giving “advice” on home schooling or on community co-op schooling. I think all the educational ideas mentioned in relation to this post are GREAT ones.I was addressing the institutional applicability of Dave Pollard’s model on a vast (state-wide, province-wide, national and/or international) scale. There are MANY social, political, and physical, complexities and conflicts that Dave’s model does not address. The public schools are heavily burdened with ALL of these complexities and conflicts.If we’re going to look at broad and far reaching educational solutions, it behooves us to include the problem areas in those.Public schools are MANDATED to be fully, and without exception, INCLUSIVE OF ALL WHO COME TO ATTEND.That means they face ALL of the problems that exist in the greater society. And while addressing and safeguarding against those problems, they must also attempt to teach.It is easy to slam the public school system while holding up a better-looking alternative. But I think the alternative should include contingencies, strategies, and methodologies applicable to the broadest citizenry.Some major problems Dave didn’t address:Child Abuse and Molestation – difficult to defend against when children are outside of a public setting (i.e. in a multiplicity of less publicly visible private settings).Mental Illness and Functional Impairment – private and community co-op schools are well known, among public school administrators, for “DUMPING” these highly challenged (and challenging) students back into the more institutional public school infrastructure when they find they cannot handle them.Religious Zealotry – a constant threat to the integrity of an empirically based liberal democratic curriculum. The fanatics are always trying to infiltrate and severely limit, any and every, educational system. With millions of individualized students, this would be much harder to safeguard against.Criminal, Anti-social, and Sociopathic Behaviors – easier to identify in public settings, the public schools spend huge amounts of time and resources, trying to identify and reform these problems. In more individualized settings, these would probably be more difficult to identify and rectify.and I could go on…I think these and many more problems, now burdening the public schools, must be acknowledged and planned for, if we are to put forth an alternative educational model.

Chris: I’m so envious of your experience. I think it shows that small communities are just naturally more flexible and creative in finding answers than big, monolithic municipalities.Dave: I don’t underestimate the problems you identify. There’s a tipping point where small, community-based, systems which are open and adaptable are no longer able to cope. And then there’s a second tipping point beyond which the system is large enough that it can start to layer some ‘built in redundancy’ and checks and balances and specialty programs to allow it to cover some of its deficiencies, like the ‘diversity’ programs of large programs. It’s the ‘unhappy medium’ that most educational systems face that’s problematic.

DaveP:Not accusing you of having given in top societal expectations…I was saying that we faced them at every turn, as do all parents who choose alternatives for parenting their children.Dave’s modle is pretty close to what we are doing, but our experience grows out of a natural extension of supporting learning within our families. It is currently supported by a school board and in fact the Minister of education in BC pointed at us and said that we were exhibiting the kinds of entreprensuerial approach to education that she was looking for from parents. We were amused by the comments, but it was nice to see what we were doing taken seriously in a provincial wide context.I think what we have done here is to stretch the public education system. We are showing that a homeschooling modle can work within a public system, which I think is what you were calling for earlier, but I was objecting to your “advice” which is how I read this paragraph:No Dave, in education, you look at the context of the situation, not the ideal. Then you try (as many have with varying results) to coerce the changes that you think will be most beneficial to the most. Let the least, the rich who send their kids to the Sudbury Valleys of the world, do what they do. If you try to go for the ideal without regard to the excisting struggle, everyone gets hurt.Where I differ with that counsel is that I see it as more important to focus efforts on the most change we can do right now. As a citizen, I think my contribution is to make as much positive change as I can. I gauge my success on the depth of that change, not the span.Where I do agree with you on context is that it is important that communities as a whole have adequate ways of handling the diversities of problems that exist. Dr. Martin Brokenleg at http://www.reclaming.net has a nice model for family and community support called the Circle of Courage that isbeing used on Vancouver Island now to structure services to Aboriginal children and families. A social context like that with small scale action on structuring learning options and alternatives could go a long way to promoting Pollard’s vision while still answering your concerns.

Misspelled the URL…that’s http://www.reclaiming.net

Chris,Thanks for addressing my concerns in such a clear and concise manner. I think differences in socio/political context may have a lot to do with our slightly differing views. Let me try to explain.Here in the U.S., as I think you must be aware, we are being subjected to a sustained, clever and coercive campaign to undermine public education. The Bush administration has enacted “No Child Left Behind” under the guise of improving educational standards. As you likely are aware, he has under funded the program, placing states that have willingly adopted the program’s standards into crisis.Here in Massachusetts, we are feeling increasingly betrayed. We can see that, by enacting a (now under funded) program that mandates better test results and promises to punish under performing public schools (and students), we have been set up for failure. As a continuing adjunct, President Bush has been advocating school voucher programs. This is part of a concerted propaganda and action effort extending from the Reagan administration to now. See the history here:http://www.cnn.com/SPECIALS/2000/democracy/privateschools.publicmoney/stories/history/The latest (deeply cynical) move is to try to get “Black Leaders” on board in another attempt to legislate a national school voucher program. Bush, Cheney, and Rove, have decided to try to influence Black religious leaders with promises of government funding for their church related schools and programs. It’s an attempt to delude Black Leaders with visions of personal fame, power and influence at the expense of their mostly lower class constituents. It is a way of buying the support of minority leaders by deceiving them into thinking that they can gain greater local control. See the latest here:http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2005/01/25/politics/printable669089.shtmlThe corporatist strategy that Bush is promoting is designed to put additional and overwhelming stresses on public education while pushing the privatization and school vouchers alternative. All of this in spite of the fact that the move toward vouchers, privatization and charter schools is not doing well. See article here:http://www.ilcaonline.org/modules.php?op=modload&name=News&file=article&sid=1598&mode=thread&order=0&thold=0This is where advocacy of Dave Pollard’s model and strategy becomes frightening. Here we have a progressive and well meaning (one might even say transcendent) educational model (Dave’s) that finds itself in the middle of a divisive and coercive political atmosphere. Might Dave’s model be used, within progressive circles, to promote a system of diverting funds and resources from a faltering and overburdened public school system? Of course. President Bush is banking on such political tendencies. Mr. Bush’s corporatist vision and agenda for a two-tiered society of the super-rich and the sustainable poor, is likely well served by the political confusion ideas such as Dave’s can cause. Educational models like Dave’s will naturally migrate to the top tier, the very rich educational system, though there, the educational options will be limited to avoid awareness of class conflicts, human inequities, or environmental calamities.At the same time, poor students will be confined to a “public education” of despair, where everything they learn is directed toward practical vocational applications. Liberal, pluralist, empirically based, education in the arts and sciences will be eliminated. This is a mainstay of the corporatist vision.And it is why I stated a point of disagreement with Dave, saying'”No Dave, in education, you look at the context of the situation, not the ideal. Then you try (as many have with varying results) to coerce the changes that you think will be most beneficial to the most. Let the least, the rich who send their kids to the Sudbury Valleys of the world, do what they do. If you try to go for the ideal without regard to the existing struggle, everyone gets hurt.” I think I well understand what you are facing as a parent Chris, though our cultural context is somewhat different. I have a 10 year old in 5th grade and a 16 year old in his first year of college. The 16 year old didn’t skip two grade levels without alot of struggle and advocacy from his mother and I. And he didn’t attain his high academic performance without alot of home augmentation and advocacy of his public schooling. We all must work very hard as parents to help our children grow as their needs and interests call us to support and guide them. After each child is born, they become our main reason for being. I commend and fully support your efforts with your children.We cannot forget though, that we all live within a social and political context that is often manipulative and harmful. It’s a world of shared risks filled with more shared risks. And in order to share the risks, we must remain together in a public setting of shared resources, shared benefits, shared burdens, and shared consequences.If we do not do this, if we separate out and follow our ideals to the exclusion of the mainstream, our political presence, power and influence is infringed and marginalized. The middle-class with its’ pluralist power to politically challenge the upper classes will die. And we (in the middle-class) will fall into poverty to live helplessly under the coercive dictates of the new super rich who now feel themselves on the verge of global control.