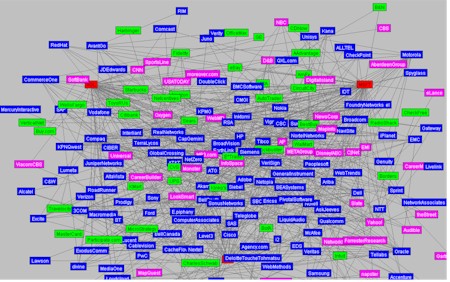

Once a month a group of us, KM directors from various companies in the greater Toronto area, get together for ‘Breakfast at Flo’s”, a trendy/retro restaurant in Yorkville, and we talk shop. We usually start with an agreed upon topic, but we go off on frequent tangents. Today we were talking about Social Networking, and why the tools designed to make it work virtually haven’t proved very effective so far. What emerged from the discussion were a set of principles which might provide some clues on how to develop Social Networking Applications that really do work, and how to establish processes that could enable and encourage effective networking in organizations. Here are the principles we came up with:

So as a result, these are the types of questions I think the designers and proponents of Social Networking Applications should be addressing:

These are not questions for programmers, analysts, sociologists or psychologists, but rather questions for cultural anthropologists, complex adaptive systems experts, and those knowledgeable about heuristics, neural networks and the Wisdom of Crowds. We need to develop much more skill in these emerging disciplines, because the old disciplines and the ‘merely complicated’ mechanisms for addressing these critical human challenges simply aren’t up to the job. As Einstein said, our current problems are not going to be solved using the same thinking that has given rise to them. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

Once we have established an impression or initial judgement, what we seem to seek most is reassurance that this initial assessment was valid. This introduces some obvious dangers: ideological echo chambers, groupthink and the proliferation of conspiracy theories for example. And just to make the situation worse. we tend to ignore and turn off information that we cannot (or don’t want to) change, which further entrenches those first impressions and judgements.As many times as I’ve seen you write this, I’ve always wanted to argue this point with you. I think we all want to think we are open to information. What I recently found particularly interesting was when that conflicting information came from my own intuition. I did not want to change my first impression of something, not at all. It was an impression formed online, without supporting sensory input. I tried to ignore my intuition and block it out and found it difficult to want to pay attention to myself. We don’t want to be fooled. I find I am still somewhat resisting. I now want my intuition to be proven wrong now that I have accepted it. It’s an interesting study of inner turmoil to say the least.If I know this and am aware of all the facts now, yet still want my first impression to be right, then I sure can’t attempt, or even want to argue this point with you anymore. It’s a very strong dynamic; we don’t want to be fooled and we don’t want to accept that we have fooled ourselves. Yes sir, give me all the sensory input I can stand, up front, for that first impression!

Here’s a bit more perspective (mine) on why social software and social networking principles aren’t as effective as they might be inside organizations, specifically.

Much of what you say here clarifies, I think, why Flickr works so well at “social networking”, even though that is not, ostensibly, what it is ‘meant’ to do.

You may want to read the link and associated article by James Farmer. Link.

It’s very clear to me that the definition of social networking is in dire need of revision. For instance, I consider blogging social networking, and flickr, and del.icio.us, and furl, and upcoming, and even Dinnerbuzz. From the following comment it’s seems clear to me you couldn’t include any of those in your definition: “Willingness to establish a relationship with someone presupposes the existence of mutual trust, respect, context, and self-disclosure between the parties.” Huh? I establish “relationships” on a daily basis with people I’ve never met based on nothing more than utility. No offense, but that’s all you mean to me. Your words sometimes add meaningfully to my marketplace of ideas. Therefore, I establish a relationship with you by including your feed in my reader.These “relationships” are dynamic, utility-based, impersonal — and I value them highly. At about 10,000 abstract vertical feet, in gross generalities, and in the shortest space possible, here’s what I think : the SS you’re referring to has two problems: first it’s the kind built by older generation thinkers working from pre-net culturally confined conceptual models of “social” and “relationship” that involve atoms generally, and “space” specifically. We don’t need no stinkin “Cheers” in cyberspace (smiling, smiling). The second reason is too complicated to do quickly — either that or I just don’t understand it well enough yet to say it succinctly. It’ll have to wait.

Cyndy: Agreed. When the first impression is a physical one, it tends to be harder to change than a virtual one. Sometimes that makes sense, sometimes it doesn’t. But it’s human nature.Jon: Absolutely right. Corporations still see social relationships in hierarchical terms, while today the most important and valuable relationships are peer-to-peer.SB: Flick has always intrigued me as a SNA. Initially I thought it was just a substitute-blog for those without the time or inclination to write, but there definitely seems to be more at work than that.Stephen: Thanks. I’ve read Farmer’s paper twice (it is not exactly easy to read) and I confess I still don’t get his point. He seems to be saying that ‘centredness’, which is something akin to ownership and control of a space, is a prerequisite to meaningful social interaction online. I think this is putting the cart before the horse. You need to be able to access and organize all your online communications, I would agree, but that could easily be done by a spider or other aggregation tool that goes out and finds all your discussion group comments, e-mails, IMs etc. and organizes them for you. In fact such a tool would be helpful even for those who have blogs and other so-called ‘centred’ spaces. But I don’t think we all need to have our own space, our own home ground, a centred place where our identity manifests itself, as the primary virtual construct for virtual communication and social networking. In fact, I ‘know’ many people without such spaces quite well. Google Desktop is a fair first-generation tool for letting me see all of their uncentred communications in one place. In fact, they may be ahead of those of us who still need a centred space, much as we once needed an office, a filing cabinet or some other notoriously inefficient physical space to give us identity and store all our information. Appreciate the link, though, Stephen — I’m not shooting the messenger.Bob: Whatyou are talking about as ‘utility-based’ relationships have value but, I would argue, are not social relationships at all. In fact, you even call them ‘impersonal’. I see these kinds of ‘connections’ becoming, very soon, machine-to-machine (M2M) connections — very useful, but shallow, with no personal investment required. M2M will free us up for true social networking, and I do believe that trust, respect, context and self-disclosure are essential for these. I think you over-estimate the impact of technology on the ability of most people to change the way in which they network and form community and relationship with other people.

Hi Dave, I like your analyais and think that, for the most part, it is probably accurage. That said, you might want to check out http://www.openbc.com – A European based social networking system with global membership which seems to generate real results for at least some of its business members. Eric Sommer, CEO, Advanced Data Management