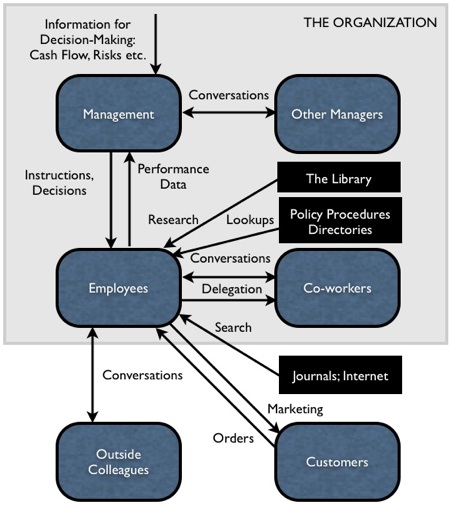

Major information flows in organizations, c. 1975 One of the most important things I’ve learned in the last few years is that, except for senior management, no one in most organizations really understands what the business of the organizations is all about — how decisions are made, what information is used and how, etc. And, at the same time, senior management really has no clue about what goes on at the front lines of their organization, or outside their organization — what potential new recruits think, what customers really think about the organization, etc. This should be obvious, if you think about it. Senior managers are insulated from the front lines and customers. No one wants to tell the boss what’s wrong with the organization — it’s a career-limiting move. And senior managers are too busy to spend much quality time with either employees or customers. To the extent they interact with customers it’s with the senior managers of those customers, who are likewise unenlightened about what is going on in their own organizations. So decisions are made, often, in a vacuum, based on deficient and filtered information. As for the line employees, they usually have never been exposed to or taught about what goes on in other parts of the organization, or how managers make decisions. This is getting worse: The current generation of young employees are likely to work in 12 organizations in their careers — not enough time to really figure out “the business of the business” in any of them. The tragedy is that often neither they nor their senior managers think they need to know what the business is all about, unless and until they become senior managers themselves. So most employees spend their entire careers feeling under-appreciated, disconnected, unconsulted, and annoyed at stupid instructions and useless information requests from management. An they have a ton of very useful information about customers, operational ineffectiveness, and what’s going on in the world and the marketplace, that is never solicited, and never proffered. I care about all this because I have spent about 1/3 of my career in an area called Knowledge Management. This discipline began about 15 years ago, and has largely followed the track of other business ‘fads’ like business process reengineering and total quality management — a flurry of investment and enthusiasm, followed by disenchantment and finally abandonment. The problem with KM is that the people charged with introducing it into organizations were mostly front-line back-office people — middle managers with a background in library management, IT or training. Few of them really knew how decisions were made and resources allocated in their organizations. The library people saw KM as a content management exercise. The IT people saw KM as a set of technology projects (intranets, extranets, groupware). The training people saw KM as an e-learning vehicle. Senior managers were mostly unenthusiastic, worried that it would spawn more IT bureaucracy like e-mail, and not seeing any new value provided by it. Their hope, tragically, was that KM might automate some back office functions and allow cost savings (e.g. blowing up the corporate library). We might be able to understand the reasons for KM’s failure if we looked through the eyes of senior managers, front-line employees, and customers, at the value of information to organizations. The diagram above shows how this looked in the days before ubiquitous computers — say, in 1975. At that time, internal memos, typed up by secretaries, instructed front-line and back-office employees what to do, and required them to report production data that managers could use for making decisions. Written information flowed vertically, not horizontally. Managers talked with other managers, and employees talked with other employees, and occasionally with outside colleagues, to learn their jobs and share what they had learned. A few employees had started using the Internet and other electronic sources of information for research, but most research was done using the internal library or outside journals. Customers received printed marketing material from the organization, and submitted their orders. These were the principal information flows in organizations at that time. This actually made a lot of sense, when you consider how senior managers saw, and operated, their organizations. The job of senior managers was and is to make the organization sustainable. Managers do this by making critical decisions, issuing instructions, capturing performance data, and tweaking those decisions accordingly. The variables they need to watch and make decisions about are:

To manage cash flow, they pressure employees to find ways to increase sales and reduce costs. Budgets, resource allocations, and monthly targets and reporting are their levers for doing so. To manage share price, they need to ensure that cash flow is always steadily rising. When cash flow from operations fails to meet targets, they look at layoffs, outsourcing, capital budget reductions, increasing government incentives through lobbying, cutting dividends or reorganizing (e.g. divesting unprofitable operations). To manage risks, they will acquire, sue or out-advertise competitors, hire PR firms to whitewash and greenwash their social and environmental misdeeds, put controls in place to reduce risk of fraud, buy insurance and hedges to reduce exposure to rate changes and disasters, lobby against new regulations, lock in or acquire suppliers, outsource non-critical operations. To manage opportunity, a few will invest in innovation, but for most larger organizations, it is much safer to acquire small innovative companies, to use leverage (borrow from the bank) when interest rates are lower than profit margins, and through planned obsolescence by constantly forcing customers to replace or upgrade, and locking them in to the organization’s product. This is what senior managers do. It is not surprising, therefore, that they tend to see IT, KM and training as “non-value-added” activities. They were getting the information they needed before the advent of computers, so why should they invest in new IT and KM projects? And since they expect and receive little loyalty from employees, why should they invest in training them, when the essential knowledge they need must be obtained “on-the-job” anyway? In the 1980s and 1990s, most organizations invested in three new technologies, mostly reluctantly: fax, e-mail, and intranets. Fax was a faster and cheaper way to send marketing materials to customers and to receive orders, and send instructions to and collect performance data from remote operations, and it was not an expensive technology to introduce. Its heyday was a mere decade. E-mail and corporate intranets were introduced in most organizations in the 1990s. Senior managers expressed concerns that e-mail would be a scourge, and many attempted to limit its use. They were right about it being a scourge, but not successful in limiting its use. It was a stealth success — permitted because it was not that expensive, but quickly used for mostly inappropriate purposes. Corporate intranets were used at first to automate the two dominant types of shared organizational information: policies and procedures, and directories. Eliminating hard-copy manuals and directories was a welcome change, but intranets quickly became massive repositories for millions of context-free archived documents that were of almost no use to anyone but the author. The consequence has been an explosion in complex server technologies, taxonomies and search technologies — for information that almost no one finds to be of any value. Documents touted as ‘reusable best practices’ were dumped into the corporate intranet and abandoned. Some organizations ended up hiring intranet ‘garbage collectors’ to remove the most useless and obsolete content. To try to connect to customers, many organizations in the 1990s and 2000s have invested in ‘extranets’ (websites that only customers had access to) and sophisticated, interactive public websites. They found to their chagrin that decision-makers in most organizations were too busy to visit their websites, and that most of the people browsing the web pages they had so carefully crafted were job-seekers, students doing papers, the competitors, and the media. So here we are in 2009, and the principal information flows in most organizations are still exactly what they were in 1975, as depicted in the chart above. What’s changed:

In other words, in adding to the volume and complexity of information systems, we have added relatively little value, and in some cases actually reduced value. The reason for this is simple:

We have, in short, implemented a solution that addressed no problem. We introduced new KM tools because we could. If that were the end of the story, we could just shrug off KM as another business fad and move on. But there is something happening in organizations today that is beginning to improve the quality of information and the effectiveness of information flows that matter, something that creates a second opportunity for KM people to actually do something useful. What is happening is that people are beginning to manage their own information, and information processes. They are finding workarounds to the dysfunctional processes in the organizations they work in. They are finding ways to draw on people in their growing online networks to do their jobs better. They are realizing that, if tomorrow’s workers will end up working in a dozen different jobs in their lifetimes, they need to take responsibility for their own learning and their own knowledge, and take it with them from one job to the next. Increasingly, they are keeping their knowledge in their own personal repositories, and in their own personal networks. I have written before about what I call Personal Knowledge Management, which is an attempt to enable workers to do this more effectively. My problem was that PKM is impossible to sell to senior management, because it has no value for them. I toyed with the idea of trying to sell it front-line workers directly, perhaps by starting a magazine called Working Smarter. The problem with this is that everyone is at a different stage in their evolution towards PKM, and there are no standard answers or approaches — we each have to muddle this through for ourselves, based on our own ‘knowledge set’ and information behaviours. But perhaps if we outlined a future scenario of where this PKM trend is headed, we might be able to evolve an approach that would accommodate the needs of both individual workers and the organizations struggling to cope with this phenomenon. To this end, let me start with a story of a young business analyst named Jon: Jon spent the first week in his new job with Giant Co. trying to port all the information, contacts, subscriptions, and software tools he had been using in his three previous jobs to his new company-supplied computer. He was stymied at every turn. He was not allowed to put the tools he was familiar with onto his new computer because they were “not supported” by his new employer. He was blocked by the security firewall from using webmail in the office (“we consider this to be something employees would only use for personal non-business purposes”) even though all his business contacts and subscriptions were on it. He was blocked from accessing YouTube (where many of the videos he had prepared for his previous employers, and some educational videos he referred to regularly, were stored). He was blocked from using IM and Skype, so he was cut off from his global network of experts and colleagues who used IM and Skype exclusively for instant, free knowledge sharing, advice, and quick lookups of useful research materials. He was blocked from using Vyew, so instead of being able to call people outside the office for quick, free conferences with screen-sharing, he had to use the company’s expensive pay-per-use audio conferencing system (and everyone on the call had to be pre-authorized), and send a huge deck of screen captures by e-mail to participants in advance. He wasn’t permitted to work from home. When we worked on weekends from home, his web access to his work e-mail didn’t work properly, and because his co-workers didn’t use it, he was told it would be months before they would start trying to fix the problems with it. After a long delay, he was approved for VPN, but only on his work computer, so he began lugging it home every day, only to discover that it degraded performance so much that even accesses e-mail with it was agonizingly slow.

His boss dropped into Jon’s cubicle about six weeks after he had started work, and found Jon working away happily. But to the boss’ surprise, Jon had two computers sitting side-by-side on his desk. Jon explained that his work computer was connected to the organization’s network, and he used it only to access messages and documents behind the firewall, which Jon would immediately forward to his personal e-mail account, or (using a USB drive) quickly transfer over to his own machine. All work was done on Jon’s own machine, which was connected to the Internet (and all Jon’s contacts, subscriptions and documents) by a wireless connection that Jon paid for personally. Because all Jon’s outgoing e-mails came from his own machine, 90% of the e-mail he was receiving from fellow employees was now being sent to his personal e-mail address (most people didn’t notice or care that Jon’s ‘reply to’ e-mail address on his messages wasn’t his company e-mail address). Ten of his co-workers at the company had followed his two-computer example, and were using IM rather than e-mail for their communications. The boss asked whether it didn’t take a lot of time to transfer between the two machines, and Jon replied “Less and less all the time”. Jon’s boss left the office unsure whether to praise Jon for his innovative workaround, or report him to IT to make sure Jon wasn’t exposing the company to security risks. This is a composite of a number of real cases of young people working around dysfunctional information systems I have witnessed in the last two years. I expect it’s going to become more and more common. Let’s suppose that, in twenty years, Jon’s information behaviour becomes the norm. Eventually organizations will have to face the problem, and end the guerilla war that is brewing between the IT security people and Gen Y in a growing number of companies and institutions. I think it is unlikely that most will be able to resolve the perceived security threats in such a way that they could allow the Jons of the world to do what they want inside the firewall. What is more likely is that, just like the calculator and telephone, the laptop (soon to become even smaller and more powerful) will evolve to be a ubiquitous personal device that people will carry with them everywhere. At that point having redundant computers (and phones) on everyone’s desk will become absurd, and IT security can start to focus on protecting confidential data from being accessed, rather than trying to lock down employees’ appliances. At that point, the role of the rest of IT, and KM, will have to change completely. Here’s a scenario of how I think it might look: In 2025, every individual in every organization uses their own personal computer for both personal and work applications. Almost all information is Web-based, with organizations’ proprietary information only accessible through authorization software. E-mail has disappeared, replaced by a virtual presence application that includes instant messaging, screensharing, voice/videoconferencing, filesharing, calendaring, tasklists. Employees maintain a Company Sector on their machines in which they put information that can be accessed 24/7 by other employees. Most people also maintain a Public Sector on their machines in which they put information that can be accessed 24/7 or subscribed to by anyone in the world (this has replaced blogs and applications like Facebook), and Community Sectors in which they put information that can be accessed 24/7 by other members of that Community. The aggregation of the Company Sectors of all employees of an organization replaces the corporate Intranet of past generations; it can be viewed by anyone in that organization. The aggregation of the Community Sectors of all members of a particular community replaces the community tools (forums, wikis etc.) of past generations; it can be viewed by anyone in that community. The IT department is still responsible for maintaining security around the organization’s proprietary information, but very little content is left in this category. IT also checks that the information in employees’ machines’ Company Sectors is appropriate for sharing, and auto-replicating properly. The KM department still manages the purchase of external information, though almost all information in 2025 is free; information producers have realized that their business model is to apply that information to specific customers’ business environment, in consulting assignments, rather than trying to sell publications. Most of the mainstream media were nationalized after they went bankrupt using their traditional business models, and now operate as public services. Most of what the KM department does now is trying to facilitate more effective conversations among people within the organization and with people outside the organization, including customers. They facilitate many meetings that use the virtual presence application, especially those that involve more than five people. That facilitation includes organizing the meeting, distributing advance materials, facilitating the discussion (conflict resolution, staying on schedule etc.), and even recording, editing and publishing the meeting as appropriate. They run courses in effective conversation, meeting and presentation skills. In addition, the KM department conducts environmental scans and conducts research in areas the organization wants to focus on, and publishes and runs short video presentations on the results. They also browse the content of the aggregate of the Company Sectors of all employees of the organization, notifying managers and employees of content that may be worthy of follow-up, and they assist employees to manage their subscriptions to people’s Public Sector content. And, when the organization holds sessions and conferences on strategy, risk, innovation or customer relationships, the KM department is on hand to do advance and just-in-time research. . . . . . If you’re in KM, or in a business that has a KM function, I’d be interested in your thoughts on this. I’ve been known to be a bit ahead of my time in thinking about the future of business and technology, but I think this scenario is quite feasible. The organizers of this fall’s KM World conference are looking for some thought leadership in this area, and I plan to use this article to provoke some ideas from those who have been working in this area as long as I have. So tell me what you think. Category: Knowledge Management

|

Hi Dave – you should take a look at Knowledge Networking from http://www.personall.fr/en/ which is close to hitting the mark on what’s next after KM !Also see The PersonAll-ization of Knowledge Work The AppGap http://bit.ly/58ABI ( you know the author Jon Husband )

Is it significant that the term “social media” is used only once in tis article and the term “social networking” not at all?

I have a different view from yours Mr Dave. I do not believe that KM in any organisation fails because it is handled by Librarians or IT professionals. Librarians and IT professionals are basically the service providers. They only facilitate things to happen. I feel, it is the lack of support from the top management which slumps any such move. The top management need to drive it and KM as such is more of socialization, externalisation, combination and internalisation (SECI model). Your thinking of personalising the knowledge some how is not palatable. KM is for organisation and not for individuals. Individuals, in any case, will have their own system of KM. As I have understood KM is bringing together the explicit, implicit and tacit knowledge into the repository (organizational memory); giving adequate access to the right people at the right time; and aid in organizational learning for effectively carrying out the business.I also believe that the Economic recession that we all experience now is because the prominence given to the “so called smart workers”. In other words they are the hoarders of knowledge (in your words PKM) and good boss-managers. PKM will promote heroisms and lead to disasters like the one we are undergoing “recessions”.

Thanks for the ideas. Do you see innovation in this area going faster in the social sector, where people are involved because of an issue, rather than a paycheck, and may be more receiptive to innovating new ways of working to solve problems?