Back to Toronto early from the BALLE conference in Denver this past weekend. I wrenched my back getting up after sitting too long on a concrete floor (the only electrical outlets for my laptop in the huge meeting room were by the floor at the back of the room). I knew one day my addiction to technology would be my downfall. Another form of information sickness?

“A network of dense clusters has fewer connections than if everyone were connected to everyone, but still puts everyone at most three degrees of separation from everyone else.” I finally got around to reading Clay Shirky’s Here Comes Everybody. The thesis of the book is that technology itself isn’t what brings about social change, it’s the behaviour change once the technology becomes ubiquitous that does so. For example, he says, the intellectual landscape of the Reformation wasn’t caused by the invention of movable type and the printing press, but it was made possible by those technologies. For social networking to work, he says, you need, in order, three things:

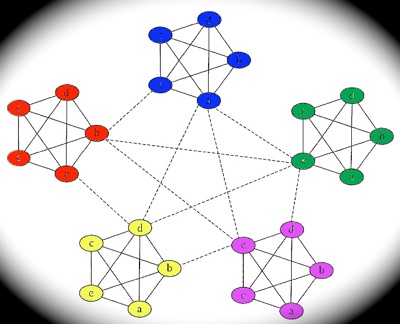

So for example, Open Space Technology works because it’s premised on an invitation that will ensure that only those who find that invitation (promise) compelling will show up; it has a well-honed self-management methodology (tool) that enables members who show up to collaborate to achieve shared objectives; and it provides a mechanism called ‘the law of two feet’ (bargain) that ensures everyone will get as much out of the Open Space event as possible. Sometimes it takes a lot of work to extend the promise (Caterina Fake said the success of Flickr depended on the premise that “you have to greet the first 10,000 users personally”). The promise and tool must address a real need: Shirky notes wryly “If you designed a better shovel, people would not rush out to dig more ditches”. I realized too late (after I’d made a promise in my book) that the website that I’d planned to accompany the book did not (and does not) meet these criteria — there is (as yet) no tool that can deliver on this promise (the promise being to help people find potential partners for their sustainable enterprises, such that the site would become an ‘incubator’). More about this sad site in a moment. The big shift that social networking (the actions that occur when you have the plausible promise, the effective tool and the acceptable bargain in place) makes possible, Shirky says, is that large scale group activities and political/social actions that once required an expensive, hierarchical organization to accomplish, can now be done by self-managed collaborative groups — and faster, cheaper, and more congenially to boot. These traditional organizations need to spend a lot of time and money attracting, motivating and managing the hierarchy. When these costs of hierarchy exceed the benefits they produce, ‘markets’ of organizations start to outperform single monolithic ‘organizations’. An interesting side-effect of this that I’ve observed in organizations with many young people is that, to Gen Y’ers, the ‘costs’ of compliance with ineffective constraints (processes, restrictions on software access, and rules) quickly exceed the value (job security), so they are finding workarounds that bypass these constraints and set up ‘markets’ for other ways of doing things (use of processes that they’ve imported from friends’ organizations or from previous experience, or use of free commercial software tools). The use of these unapproved ‘insecure’ processes and tools has set the stage in many organizations for a culture war between the older, command-and-control style of senior management and the new, peer-to-peer, workaround-based style of Gen Y’ers, powered mainly by social networking. As Shirky puts it (and Dave Snowden has illustrated in many case studies) “employees do better at sharing information with one another directly than when they go through official channels.” It enables them to do their jobs more effectively, and for many employees (especially the young) that’s more important than doing what they’re told. The result is an epic battle for control of what goes on in the organization, and in fact for control of the organization. Shirky asks, and doesn’t really answer, the critical question that has prevented my book’s website (and a ton of other sites and social networking tools) from doing its intended job: How do you reach the people you want, without having to broadcast your message to everybody? The book kind of implies an answer, though (using the successes and failures of Meetup.com as his case study). The answer is you don’t; you let the people you want to reach find you. This is now the challenge that I’m going to apply in rethinking my book’s website. Instead of trying to attract millions of prospective entrepreneurs to my site (effectively reinventing marginally effective social networking tools like LinkedIn), how can I enable anyone looking for partners in a new sustainable business (what Shirky calls ‘latent groups’) to find and ‘Meetup’ with each other using some combination or mashup of existing social networking tools? If you’re a whiz a social networking, and have some ideas on this (that meet Shirky’s three criteria) please let me know; I’d be pleased to have some real-time conversations on this. Enough about my book; back to Shirky’s. He observes that the fact that in large organizations information travels vertically, one layer at a time, and poorly (instructions flow rigidly top-down, and information requested by managers flows up, appropriately filtered so bad news never makes it to the corner offices, because no one want to tell the boss bad news, and s/he doesn’t really want to hear it anyway) is inherent in the very design of managerial culture — it’s the way organizations prevent the ‘information overload’ that peer-to-peer communications and messages that skip levels in the hierarchy would otherwise produce. Social networking ‘tasks’, he says, fall into three categories: in increasing order of both difficulty and potential value they are (1) sharing/coordination, (2) conversation/cooperation, and (3) collaboration (collective action). I’ve written about these three forms of group activity before. The third category requires a strong enough shared vision that decisions that some members don’t like won’t be enough to drive them out of the group — these, he says, are rare. An important emerging phenomenon of social networking tools is what he calls “mass amateurization”– the capacity of non-professionals to do what was always professional work: “Just as you no longer need to be a professional driver to drive, you no longer have to be a professional publisher to publish.” It’s interesting to think about whether every profession (doctors, lawyers, teachers, accountants) might be doomed by this phenomenon. Will a million people passionately collaborating to help each other deal with a shared disease eliminate the need for expensive specialists in that disease (except perhaps for the actual surgery)? Will ‘peer production’ replace what all professionals do today? While social networking technology enables individuals and groups to do some things they could never do before, the dilemma (a consequence of Shirky’s now-famous Power Law) is that social limitations quickly replace the technological limitations. Once bloggers become ‘famous’ they lose the important ability to communicate at any meaningful level with their individual readers. Bloggers with a dozen readers, he says “don’t have a small audience, they don’t have an audience at all; they have friends.” Interactive TV is an oxymoron, he says, because “gathering an audience at TV scale defeats anything more interactive than voting for someone on American Idol”. A few e-mail messages allow you to converse powerfully with people anywhere in the world, but 100 e-mails a day prevents you from meaningfully conversing with anyone. So those will large audiences broadcast, and those with small audiences converse. The most effective networks draw on both: clusters of small tight networks loosely ‘bridged’ by Gladwell’s ‘connectors’ into large networks with many members spreading the word (see illustration above). The challenge is to get the balance right. The most specific groups (e.g. wiccans in Omaha) tend to bond best, but never achieve critical mass. Those with the most potential members (e.g. environmentalists) are too broad in scope to attract a devoted and attentive membership. Meetup.com solved this problem of size/specificity optimization by leaving it to the users themselves. I thought about this in the context of the challenge for prospective entrepreneurs to find each other and to find their ‘audience’ — i.e. the customers who need something the enterprise provides. Perhaps, I thought, I’m trying to bring together the wrong groups of people. What if, instead of a ‘dating service’ site for prospective entrepreneurs, I was to create a series of unconferences not of prospective entrepreneurs but of needy people — people who share an unmet, and probably unarticulated, need? So, for example, what if we brought together people struggling to find healthy, local, organic food? Prospective entrepreneurs who cared about the issue of healthy food would be invited to sit upstairs in the audience and just listen. Then, once the size and scope and nature of the needs had been articulated, the prospective entrepreneur ‘audience’ would come down to the floor and brainstorm possible ways of meeting that articulated need. The needy customer group would indicate whether they would ‘buy’ any of the proposed solutions of the prospective entrepreneurs or not. As in all complex problem situations, the problem and the solution would co-evolve. Partnerships (perhaps including both prospective entrepreneurs and customers) and enterprises would emerge naturally. Could this ‘customer-supplier’ enterprise co-development model work? What kinds of ‘unmet need’ problems might it work for, and scale to? Would it work for intractible, ‘wicked’ problems like community poverty and urban sprawl? As social creatures, Shirky says, we make meaning out of information through conversation. The value of the content itself, he says (in a message everyone in the ‘Knowledge Management’ business should pay attention to) is nothing but fodder for sense-making conversations. Or as Cory Doctorow puts it “Conversation is king. Content is just something to talk about.” And ultimately, Shirky argues, “all businesses are media businesses, because they rely on the management of information” for their employees and customers. Because of the power of social networking, “the more an industry relies on information as its core product, the greater and more complete the change [that social networking will have on it] will be.” I’m not a believer in the value of trying to achieve large-scale social or political change through networks (the fix is in, and a million small, poor voices will rarely achieve what one rich lobbyist can). So I don’t have much to say about Shirky’s suggestions on making such political activism movements more effective. He makes some interesting comments on the Bowling Alone hypothesis (that many modern American phenomena like suburbanization have fractured Americans’ participation in groups, and drastically reduced the nation’s ‘social capital’ as a result). Some social networking tools and activities (like Meetup) are, he says, attempts to rediscover and reestablish that social capital. He also talks about how Open Source capitalizes on social networking: “Open source is a profound threat, not because the open source ecosystem is outsucceeding commercial efforts but because it is outfailing them.” We learn from mistakes, and social networking lets us make mistakes faster and cheaper than any ommercial organization can match. What this teaches us is that “the communnal can be at least as durable as the commercial. For any software, the question ‘Do the people who like it take care of each other?’ turns out to be a better predictor of success than ‘What’s the business model?’ ” One point he makes that I found intriguing (and frightening) is that social networking is far more effective for passionate cadres of loosely-linked extremist groups than it is for citizens with more than one issue in their agenda. What will happen when it’s discovered that social media are enabling the desperate and the criminal to do their work more effectively? Will there be an outcry for censorship of these tools? So if you haven’t bought or borrowed Here Comes Everybody yet, I’d recommend it highly. And I’d love your comments on the four sets of questions I ask (in red) above. Category: Social Networking

|

Shirky asks, and doesn’t really answer, the critical question that has prevented my book’s website (and a ton of other sites and social networking tools) from doing its intended job: How do you reach the people you want, without having to broadcast your message to everybody?The book kind of implies an answer, though (using the successes and failures of Meetup.com as his case study). The answer is you don’t; you let the people you want to reach find you.I think his inchoate answer is basically correct and I think that we are all learning all the time in these still-early days of online information circulation various ways to help them find you.

The idea of “peer production” is interesting and, obviously, in some areas it is a good solution to top-heavy organizations trying (poorly) to fill a need. But I’m not sure how well it scales and, anyway, I’m skeptical of any one ideology that suggests it has a solution for every problem. The only circle I travel in with respect to this discussion is yours and Rob Paterson’s blog. Rob says that everything can be solved with this model. It’s a faith-based religion.One thing I find a bit distasteful about the whole thing is that it talks about “peer production” but is really about peer production by someone else once the new elites (i.e. the ones with these blogs — yes, it sounds funny) put the system in place for you to do it. The least you’d expect of someone who was railing against industrial agriculture and was interested in a peer-based solution, for example, is that they use their own land to try something different.Sharing information on diagnoses requires a shared mindset about how you will collect and organize data so that the data are comparable between groups. As someone interested in knowledge management, obviously you know this… but we have this widely-accepted system already. It’s called the scientific method. Maybe it has been compromised by big business, but the underlying system is a good one.Local solutions save the world? Look at local village governments in China.Essentially, I see the peer-based alternative as an interesting idea that would provide temporary relief from widespread corruption until the new system found a way to become corrupt. Many of the “green shoots” of peer-based systems — Twitter, Facebook, peer product reviews, etc. have already been infiltrated by corruption. And, of course, you are probably aware that there are CIA ties in the Facebook funding chain.So, I don’t like the idea of peer-based production as a universal model, but it will work well for some problems. Other than a general distrust in the population and perhaps a misalignment of interests with employment that leaves people exhausted at the end of the workday, I don’t see what is stopping this from happening if the interest is there.Something else on movements like environmentalists… I think it’s difficult to organize those because environmentalism is essentially a socially-acceptable outlet for people that don’t like humans to criticize humanity. Some people are serious about environmentalism, but I’m not sure they’re the majority. Other activist movements are ways to criticize a society from which they’re ostracized until they become invested in it (i.e. students, until they get a job) It’s challenging to decrypt the real intentions of people. But that’s true of activism in general… it’s so one-sided that you can’t believe anyone really believes what they are saying deep inside. It’s only a matter of time before they become ashamed of themselves and their dishonesty and lose the ability to express their lies with a passably-authentic passion. Of course, if you just hate everything around you then you can continually keep the fire stoked… and I think that describes a lot of activists. But it makes them difficult to organize because your one cause is just a subset of what they hate. If your cause gets boring or socially unappealing, there are plenty of others to move onto. Or maybe they just calm down and get a job and a family and find some happiness and develop an interest in perpetuating stability and peace.

Dave, I’ve been asking myself a lot of the same questions. As we speak, people *are* finding each other, everywhere out there, in the chaos that is the social web.The closest a web site could get to catalyzing this process, I guess, would be by providing an “attraction center” for self-identification that is strong enough that people who connect to it see it as the perfect place for “their kind of people” and are motivated to find each other in there, rather than out of there.The thing is, the more specific the interest or shared goal, the stronger the felt affiliation. I wonder if “I want to build a sustainable business” is a strong enough shared goal that many people will commit and stick around. True, you could subdivide, but without specific branding at each level it looks challenging.

I heard someone interviewed about the following site a couple or so weeks ago. Now, having just read this post of yours I immediately thought it might be something you’d be interested in checking out, Dave? Innocentive “where the world innovates”. It’s certainly an intriguing concept which seems to have connected in a number instances.Cheers,