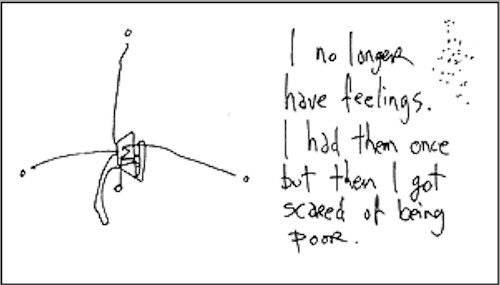

drawing by hugh mcleod at gaping void

In my recent post The Freedom to Do Nothing, I quoted Ran Prieur:

When you begin to get free, you will get depressed. It works like this: When you were three years old, if your parents weren’t too bad, you knew how to play spontaneously. Then you had to go to school, where everything you did was required. The worst thing is that even the fun activities, like singing songs and playing games, were commanded under threat of punishment. So even play got tied up in your mind with a control structure, and severed from the life inside you. If you were “rebellious”, you preserved the life inside you by connecting it to forbidden activities, which are usually forbidden for good reasons, and when your rebellion ended in suffering and failure, you figured the life inside you was not to be trusted. If you were “obedient”, you simply crushed the life inside you almost to death.

Freedom means you’re not punished for saying no. The most fundamental freedom is the freedom to do nothing. But when you get this freedom, after many years of activities that were forced, nothing is all you want to do. You might start projects that seem like the kind of thing you’re supposed to love doing, music or writing or art, and not finish because nobody is forcing you to finish and it’s not really what you want to do. It could take months, if you’re lucky, or more likely years, before you can build up the life inside you to an intensity where it can drive projects that you actually enjoy and finish, and then it will take more time before you build up enough skill that other people recognize your actions as valuable.

This has certainly been true in my case. Now that I’m comfortably retired from paid work, I have the freedom to do nothing. I’ve been through a long list of things I think I should be doing (and should be passionate about doing), and realized that I haven’t the heart for them. I thought I wanted to work to stop the Alberta Tar Sands, and the atrocity of factory farming. I thought I wanted to create a model community, or at least be part of one. I thought I wanted to increase my connection to my emotions, to others, to all-life-on-Earth, to increase my resilience, capacities and competencies in ways that would be useful to the world.

But I don’t really want to do these things. At least not enough to overcome my internal resistance to getting to work on them. There are, I think, three main reasons for this (these are not excuses, merely explanations):

- I’m exhausted. For now, I just don’t want to work that hard at anything. I want things to be easy, and/or fun, at least for a little while until I am less tired, less worn out.

- I don’t think I could handle the stress. As I wrote recently, I have learned that I am anxious and fearful (of many things) and fragile and no use to the world broken, and I think working on these projects would break me, or at least my heart, to the point I would simply have to stop, and perhaps might never recover.

- I’m not convinced they would or will, in the long run, make any real difference. Industrial civilization has so much momentum, and is taking us over the edge of the cliff at such a pace, that trying to slow it down or divert it seems futile to me. In his latest book Twelve by Twelve (more about this book in an upcoming post), conservationist and international development aide William Powers laments that his work often seems pointless when years of hard work by conservationists can be more than undone by the forces of mindless globalization in a matter of days. When I speak with climate scientists, I find them utterly overwhelmed and filled with despair. The handful of credible economists and energy experts I follow are uniformly pessimistic that the idealistic pursuits of alternative economy movements and transition initiatives have even the faintest hope of working.

So, I keep asking myself, If not that, then what? What do I want to do with all this freedom I’ve just discovered I have? I know I don’t want to do permaculture gardening, which many of the post-civ writers I most admire do. I know local food security and sustainability are important; I just have no calling for them. I know I don’t want to chain myself to tractors or blow up dams or blockade roads or spike trees or break open the closed doors and cages of suffering farmed animals, as much as I know this work needs to be done and hugely admire those who do it. I don’t want to lobby or petition politicians or protest in the streets, in part because, as my friend Keith Farnish argues, this light green environmentalism merely plays into the existing power structure, and changes nothing. I don’t want to write op ed pieces or give talks or teach or otherwise try to persuade people what they don’t want to hear, or act upon.

What is the point of changing people’s beliefs? In the 1960s and 1970s we did manage to get a lot of people to think differently about a lot of things. But what has actually changed since 1970? In 40 years, what are the major changes in the Western world (I won’t presume to identify what major changes have transpired in the rest of the world). I think there have been six real megatrends in that 40 years, and none of them is good:

- Inequality and Desolation: Expectations regarding income, wealth and job security, for the large majority, have dropped. Average family assets have doubled but average family debts have tripled, so net wealth has not changed. It now takes two incomes to provide what one income could provide in 1970. Resource use and environmental damage have skyrocketed, and almost all of the wealth produced by that use and damage has accrued to less than 1% of the population, which is now obscenely rich. And the damage and inequality are accelerating, even under liberal regimes.

- Crumbling Public Institutions: Health and education systems, which most people believe to be the two most important services provided by the public sector, have steadily and seriously deteriorated since 1970 to the point that in many countries they are dysfunctional and teetering on collapse.

- Soaring Ignorance and Mindless Consumerism: The information media have so thoroughly discredited themselves since 1970 that now, virtually no one pays any attention to them or discusses any real news or important current events or problems. As people have stopped believing or buying their ‘information’, they have converted themselves into pure entertainment media, which has been much more profitable for them, since it requires no thorough, critical or investigative journalism, and focuses instead on celebrity gossip, trivia, fear-mongering and sensationalism.

- Staggering Technology Waste: Trillions have been spent on much-hyped ‘improvements’ in information and communication technologies, but for the vast majority, the principal technology remains the telephone, and the amount of information and the quality of communication of the average user of these extravagant technologies have actually significantly dropped compared to 1970.

- Endemic Political Cynicism: The idealism of the 1970s has morphed into the anomie and anger of the current decade, and interest and participation in the political process have plummeted.

- Social Disintegration: The exuberant “whole world is watching” sense of global community and collectivism that prevailed in 1970 has been replaced in 2010 by a new tribalism characterized by extreme individualism, a loathing for government regulation, disenchantment with the idea of single-tier egalitarian essential public services, atomization and anonymization of communities, and the commensurate rise in power of ruthless gangs (street, drug, oligopolist and corporatist).

This is what the idealistic hippie-boomer generation, that vowed to change the world 40 years ago, has actually produced. For all the talk, this is what we’ve shown. How can anyone take seriously the blatherings of those who say we’re at the dawn of some new (social network enabled) global consciousness raising? What real difference has the largest, richest, most educated generation in the history of the planet actually made, except to make the world much, much worse? And that’s despite all the efforts of those who’ve done the hard, thankless work of activism, education, innovation, and other public service — the vital holding actions that have prevented things from being even more terrible than they are. It’s a matter of no small shame to me that I was able to convince myself, for that 40 years, that I was actually doing some enduring good, when actually I was complicit by action and inaction in these six distressing trends, and, aside from benefiting financially (which has at least reduced my fears and anxieties about being poor), it was 40 years largely wasted.

I’ve said before that my distinctive competencies are writing and imagining possibilities, so I keep thinking that perhaps my gift to the world is stories — about how the world really is (in contrast to how the media portray it), and about how we might live better. But what good have stories done so far? Even if they change beliefs, what does it matter if the behaviour, the stuff people actually do, is activities that produce, perpetuate and accelerate the six megatrends above? In my post last year called No More Stories I wrote:

I am coming to believe that all stories, from the unactionable dumbed-down crap that we’re fed by the mainstream media, to the preposterous ‘history’ they pass off as ‘fact’ in so-called institutions of learning, to the regurgitated tripe from Hollywood, to the mountains of lies of corporatists in their greenwashing and advertising, to the formulaic and emotionally manipulative fiction to which we escape from our brutal and mind-numbing lives — are propaganda. They are meant to keep us in our place and distract us from discovering what is really going on in this world. Stories, I am beginning to think, are just more of civilization’s gunk that gets layered on us (some of it self-inflicted) from the moment we acquire the dreadful skill of human language, stuff that prevents us from being nobody-but-ourselves, and from understanding what is really needed, now, what we have to do, with all of our hearts and our minds and our senses and our instincts.

So: damn stories. If one is inclined to “rewrite one’s own story”, perhaps it’s time to give up fiction, turn off the projector, get out of the theatre and improvise living in the real world, where there are no scripts, just work that needs to be done and actions that need to be taken, if only we can readjust our eyes to the light. The director, it turns out, is a mannequin with a pre-recorded playback device in his megaphone, and the script was written by a machine using lines selected with a random-number generator.

And the part that each of us has been playing was actually written for someone else. The set is empty, the props are all falling down and blowing away in the wind. All that is left is Now.

So what next? I have argued before that human behaviour is driven, more than anything else, by what I’ve called Pollard’s Law:

We do what we must, then we do what’s easy, and then we do what’s fun. There is no time or energy left over for doing the right thing, what we aspire to do, what we think we should do, what’s merely important. None. That’s not laziness or cynicism, it’s just the way we (and all creatures) are built. From an evolutionary perspective, it’s a successful strategy, to focus on the needs of the moment.

Let me clarify what I mean by “we do what we must”. Imperatives for action can be externally imposed (“do it or you’re fired”) or internally imposed (“I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t do this”.) It’s tautological — if a cause becomes so important to you that you can’t not be involved, then it becomes, for you, a “must”. I’ve been told by people whose courage blows me away (e.g. people whose whole lives are consumed with looking after physically or mentally handicapped relatives; and people struggling every day to cope with the endless aftermath of some horrific past trauma) that it’s not courage if you have no other choice (or believe you have no other choice). It’s just doing what you must.

So now there is nothing I “must” do, I am spending time doing what’s easy and what’s fun. And in this terrible world, when you’re informed, and feel a sense of grief and responsibility for the state of our planet, and a feeling of hopelessness to do anything about it, nothing is really easy or fun. So I’m, largely, doing nothing. Living in my sleep. It’s not bad. But it’s not enough. I owe myself, and the world, more.

When I get discouraged looking for my Sweet Spot, I often try another exercise called Future State Visioning, in which I imagine myself (say a couple of years) in the future, doing what I would like to imagine myself doing, to see if that provides any insight on what I’m meant to do, or at least what might be easy and fun.

And if I’m completely honest with myself (to the extent I know myself enough to be completely honest), I confess I imagine myself doing mostly easy, fun, and pretty useless things:

I imagine myself surrounded by beauty (wild, natural places, art and exceptional people) and peace (places of quiet, little evidence of human activity, no stressful activities or emotions being expressed), living a life of safe, stress-free stimulation. Picture a cosmopolitan group of very bright people, meeting impromptu in a pub in the Alps during a (non-strenuous) bike tour, and talking about Transition. Picture being surrounded by vivacious people, cute animals, interesting lights and shadows, ancient forests, ocean beaches, dazzling sunsets, great music. Picture falling in love, easily, all the time. Picture an extraordinary Game of Cards with people of breathtaking genius. It’s an image of extraordinary awareness and complete relaxation at the same time. Perhaps it’s an image, an imagining of being always present.

I imagine spending half of my time alone, in wild, beautiful, yet still comfortable (to this spoiled Westerner with zero survival skills) places. That “alone” time is spent in equal parts sensing (paying attention), reflecting, imagining, creating (poetry, short evocative fiction, music, film), and writing this blog (with a greater focus on imagining and conveying how we could live more self-sufficiently — unschooling, self-managed health, locally-created entertainment etc.)

I imagine myself spending the other half of my time in the company of people who are exceptional: extraordinarily intelligent, informed, sensitive, imaginative, present, articulate, and emotionally strong. I picture myself just enjoying their company silently, or collaboratively writing, creating, throwing around interesting ideas, playing. I imagine some of these people being just-for-fun lovers who, in order to have acquired the above qualities, are probably 40-somethings, but who I picture looking much younger. (That is probably pathetic and unrealistic, but I haven’t yet outgrown it. During part of my 20s, my love life was actually like this, or at least that’s how I remember it — poly, just-for-fun, joyful, uncommitted, educational, varied, ego-nourishing, free — and I miss this.)

Why should I want my companions to be intelligent, informed and articulate if I just want to enjoy their silent company, when I’m increasingly disillusioned with, and tired of, conversation? I don’t know. I guess I just want to be comfortable with them, to know they’re “my kind” of people. Perhaps, since people are often known and judged by the company they keep, I just want to be known as the kind of person who hangs out in such company — an ego thing, an insecurity perhaps.

Perhaps this is why I was (and still am) drawn to the beautiful world of Second Life. There everyone you meet “is” young and beautiful and, if you take an appreciative approach to the avatars’ actions and conversations, you can imagine your companions having whatever qualities you want them to have. Everyone, especially you, is larger than “real” life. And maybe, then, they do “really” have those qualities. Maybe we imagine people even in “real” life to be who we want them to be. Maybe we imagine ourselves to be who we want ourselves to be, instead of knowing and accepting ourselves as who we really are. An idealist’s dream.

Would I quickly get tired of this idyllic, lazy, always-present, easy/fun life I imagine, if I were able to find it in “real” life? Would I then be ready to put this Vision, which I’ve had for most of my life, behind me, and move on to something more mature, more useful to the world?

Of course, a personal Future State Vision like this is just another story, subject to the same frailties and objections to stories that I outline above. Perhaps it’s just a trap, a fiction, an impossibility to chase, futilely, narrowing my focus to the point I miss the possibilities that could arise if I just went out and did some things that are completely different, since my stories are inevitably constrained by what I know, and not open to what I have never experienced or learned about myself. Perhaps my real Sweet Spot has yet to be discovered.

As much as I accept the validity of this argument, I know myself well enough to know that (a) the things I have recently done that are completely different have turned out not to have been particularly interesting or, in my mind, worth pursuing, and (b) as soon as I venture outside my comfort zone I again run up against the risk of stress, and commensurate meltdown.

“Where do you grab the dragon’s tail?,” William Powers asks his mentor in Twelve by Twelve, thinking about the need to address climate change and other crises of our time. She replies: “I think you should grab it where the suffering grabs you the most.” But what if that suffering, that grief, grabs you so hard you ache all over, but you lack the courage, the “intestinal fortitude” as it used to be known, the emotional strength, to grab the dragon’s tail?

Maybe sometimes it’s best not to fight the dragon.

Just in case anyone is still reading this endless exercise in self-examination, this public diarizing of my semi-competent personal truth-seeking, perhaps it’s time to wrap it up. What I think I believe, for now, is:

- I should acknowledge my exhaustion and my many fears, not with the intention of trying to “fix” or change them, but just to accept them and accept that, at least for now, I should give myself time to recover, to get my strength back, appreciate who I really am and who I am not.

- Since my Vision for myself seems to revolve around always being present, I should look more actively for ways to achieve that state of simultaneous awareness and relaxation — perhaps with greater presence, my purpose, my intentions, my gift to the world, what I should do next, will become clearer. Brief anecdote: I woke up from a dream last night just at dawn and the fog outside the bedroom windows (I normally have an amazing view of mountains and ocean) was so thick that for a moment I felt as if I were floating. Suddenly I became aware of this strange sound, and listened to it carefully, and then realized that it was my breathing. For the first time I was really focused on listening to my breathing, not (as I tend to be when I try to meditate) focused on thinking about listening to my breathing. This seems an important distinction, a revelation. Is this a taste of what real presence is?

- I should acknowledge that, in some of its details at least, my Vision is not realistic, and, like all fictions, it’s a story I should, at last, let go of. No more stories. Less thinking and living inside my head. Instead: See. Be. Do.

That’s all I’ve got.

When you do a future visioning exercise, what do you see that brings you joy? When you simply ramble through your memories, what brings you joy?

What makes you want to rush to phone or email someone to share it with someone?

My prescription to you is finding joy. It’s out here. Sometimes it’s fleeting, but it makes effort worthwhile.

In Hesse’s Siddartha – he ends his life gently rowing folks across the river – Dave I am going down your road – “exhaustion” is the word that struck me in your piece – also the idea of the sheer power of the system – leaning towards having fun too or just being very gentle to myself and to others

Choosing is difficult when there are many choices. Choosing is difficult when you want to make the “right” choice. Seeing clearly can be blinding, causing a dark night of the soul. Waiting for exhaustion to exhaust itself is hard, but the only way (I believe) to reach peace and allow YOUR energy to rise and move you onward.

Dave, I appreciate your willingness to expose your feelings here on the web for anyone to read now and maybe forever.

“So What Next,” is a long rant. I found that several comments resonated with me. Some deal with what I’ll do today, and some are about what I might do for the rest of my life. And some are questions that have troubled me at one time and I’ve found a way to move past them.

The first observation is that somehow you have reached a place in your life where (or when) you are not obligated by anybody or anything to do anything. You are not required by your stomach, your family, or your culture to provide or accomplish anything.

What a tiny percentile of sentient creatures achieve that luxury! You made it here (in this circumstance, on Bowen Island, or at this point in your life) as a result of many choices you made, and probably some luck. Why, then, can you not just savour and enjoy the meal you have created for yourself?

I suspect it is because you do feel bound by a sense of obligation. The title of the blog seems to imply that you are exploring ‘how to save the world.’ If I count the words that you’ve written here, and think about the time and effort that you have dedicated to producing all of that, I gather that this sense of obligation is huge.

Maybe that obligation is worthy of your angst. And your (potential) failure to personally save the world in what remains of your life might cause you real and legitimate pain. Maybe you need that pain to cause you to address that task. You have a limited number of days to do the job, so probably not-doing it is jeopardizing your ability to achieve real meaning to your life.

Dealing with this need is not trivial. It arises out of whatever we (not ‘we’ as a community, but ‘we’ as each individual) decide is the true meaning and purpose of life. Your ‘future state visioning’ sounds boring because it looks like you are already there. All you seemed to come up with is a little redecorating of the current situation.

I don’t know what would give your life meaning and purpose. I have a couple of thoughts about that. One has to do with the kind of creature we are (you know, a member of the human species). I explored that in this old essay http://www.ballantyne.com/Do_Create.html about being doers and creators. Since I am built to create and do, I suspect that those are things that will probably make me feel good, and perhaps even fulfilled. If this thesis were correct, then I might understand why you are troubled if you are not doing and creating.

If, then, it is appropriate that you are troubled, and the solution is to do or create something, then what? And isn’t this the big payoff? Answer this one correctly and you are in a position to achieve the top tier in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

What might guide you here? You are showing the symptoms of someone who is about to make a decision. I have this tool that is sometimes helpful: http://ballantyne.com/decisionProcess.html. It is about the process, not the solution. I suspect that you are good at working through processes that can produce better results.

Back to the issue of the meaning and purpose of life. I don’t know what will resonate with you, but this spoke to me when I first heard it, years ago. Mark Vonnegut said to his dad the author, Kurt, “Father, we are here to help each other get through this thing, whatever it is.” I was pleased to find an existing reference to that quote: http://www.inthesetimes.com/article/cold_turkey/

I have another thought to add to this. I’ve come to the conclusion that nothing matters.

‘Mattering’ is something that we humans attribute to things and concepts. Intrinsically, nothing, by itself, matters. It continues not to matter until we (as individuals or as a community) layer mattering over it. The earth does not need saving until we make the choice that saving something about it matters. If you accept that something matters, accept also that that is a choice you can make. In your article you wrote lots about what you want. There is no power in wanting. The power is in making a decision or a choice.

Regarding Pollard’s Law, I think, like all natural laws, the word ‘law’ is not appropriate. In science, and in this example, the word ‘law’ would be better expressed as, ‘pretty good generalization.’ And, by the way, I think you’d be having more fun if you could begin to achieve some real traction in achieving whatever you mean by ‘saving the world.’

Of course you can do it. You did say that your distinctive competencies are ‘writing and imagining possibilities.’ Maybe your frustration has something to do with the fact that as yet, will all of that competency, you have not seen the possibility or imagined the words to describe the future that is needed. Focus your time on the task.

I think there’s a lot of grief going on here, Dave. And in the midst of that grief, it seems to me that there is a new relationship with the world and with yourself that is trying to emerge, and it won’t be rushed, and it’s simply unknowable until it reveals itself. Trying to suss it out before it’s born will just wear you out. It’s a bit like deschooling — tho not from school, in your case, but rather from a set of beliefs about who you are and what you want that no longer seem relevant. If you were a deschooling kid I’d remind you that it takes time (usually lots more than we want to allow) to get all that irrelevant stuff off us. You can’t think it away. Transitions have their own internal logic, and we’re not in charge of their unfolding. So I’d tell you to go play, and let yourself be loved. Especially that.

Please be kind to yourself and consider that your options (writing, teaching, advising, volunteering, etc.) might impact others in ways you will never know. How can anyone be comforted by falsely thinking that they’re positively impacting the world? You are (enviably) able to do what you like, but perhaps some tiny bit misses the pressure and expectations of “doing of what you must?”

I personally am trying (not always successfully) to simplify my life by only dealing with the necessities of life as “must do’s”. If you start each day with a checklist of the few physical survival requirements and then spend the rest of your day doing the easy and fun stuff, you will become a model for others to emulate.

Most of us can go through our physical needs checklist in a few seconds. Will I need to worry about securing clean safe water or food for today? Will I have safe and comfortable shelter for today? Do I have clothing for today? Is my health good? Am I safe? Most of us (especially retired folks) can answer these in a few seconds. After we do, then the rest of the day is available to do what we want.

I suggest that helping others is one of the most satisfying ways to spend your days. I do not mean that you should help others by doing things for them that they should be capable of doing for themselves. I mean that you can help others by applying your unique talents, whatever they are, to helping them see that most of life should be relaxing and enjoyable. People can only be free when they realize they only have very limited physical needs that can generally be easily satisfied. Most of the relaxation and enjoyment do not require the use of massive quantities of physical resources.

I suggest you might adopt as one of your projects developing, documenting and educating methods for people to live a relaxing, enjoyable and fulfilling life. Teach people how to convince themselves that their physical needs are easily satisfied and most of the rest of their desires can be achieved with or without large amounts of money.

Most of us are so brainwashed by the system that we have no idea how to have beauty, love, relaxation and enjoyment in our lives without spending money to have the system provide us with a cheap substitute of them.

Rayne, Rob, Joan, Robert, PS, Jenny and John. Thanks to you all for your comments, suggestions, and questions. I’m always amazed that people are willing to read through some of my navel-gazing “diary” entries, and then to respond with such caring and thoughtful comments.

Rayne, I guess my answer to all of your ‘joy’ questions would be: all kinds of “safe, stress-free stimulation”, from discovering a great new song to falling in love to hearing a brilliant new idea to a sensory delight like a sunrise or thunderstorm. All such stimulations make me feel truly present, and hence joyful.

Robert, you’re right about my feelings of obligation. My challenge is that I’m not good at making things with my hands (even music), so my gifts to the world are necessarily more abstract, and to many that means less “useful”. I appreciate your process (though I am not sure about pushing past fears), and I love the Vonnegut quote.

Peggy (I am so used to calling you PS!), you’re absolutely brilliant — one of those ‘exceptional people’ I envision myself spending time among; thanks for the wise and heartwarming counsel.

I think the good news is that to make a difference doesn’t require arresting the cliffward momentum of industrial civilization.

I’m a big fan of stigmergic organization, which doesn’t require everyone to get on the same page or convince everyone else before anyone can take a single step.

And the beauty of it is, technological changes are making the stigmergic organization of an alternative society within the old one more feasible than ever. The desktop revolution in the information/cultural realm, and the development of cheap CNC tools for micromanufacturing, mean the capital outlays for establishing small-scale relocalized production without anybody’s permission have fallen by about two orders of magnitude. When a garage factory with $10k worth of homebrew CNC machinery can do most of the kind of stuff that reqiured a million $$ factory thirty years ago, you don’t need to arrest the momentum of industrial civilization. You can just do it. Look at the hackerspace movement, Open Source Ecology, and the like. People are building a relocalized, human scale alternative parallel to the old system, without any requirement to persuade a majority of people that it’s the right thing to do.

Great piece, Dave; thanks. It is obvious many of us are in similar places; thanking you for giving voice to us. What resonates here from within my own experience and self is to continue to explore, to find that beauty [see “The Everyday Work of Art: “Awakening the Extraordinary in Your Daily Life” by Eric Booth, Authors’ Guild Back-in-Print (iUniverse.com) (ISBN 0-595-19380-3]. Find a new skill set to learn?

This past week, I am enamored of a recently-discovered piece of work by three exemplars or masters such as the ones Booth speaks of… the trio of Keith Jarrett, Jack deJohnette and Gary Peacock on the “Changeless” CD, which is elemental, pure improv, and stunningly moving. Literally, like much music, it gets you on your feet and starts the synapses firing. It made me explore the idea that, at age 62, post heart valve replacement and stroke, I could perhaps begin to learn how to play the upright double bass in the hopes of creating something so beautiful, some tiny contribution. Play is still alive. See “Free Play: Improvisation in Life and Art”, Stephen Nachmanovitch, Tarcher/Putnam, NY 1990. Or “Deep Play”, Diane Ackerman, Random House, New York, 1999.

We each must add our drop of essence to the river and the ocean; you have already been a significant rivulet.

Take it easy on your self, and just be.

Dave, what bunk! “I’m not good at making things with my hands!” I shudder to think what you created How to Save the World with –your toes? Since when are writers lesser craftsmen/artists than anyone else. What breaks your heart, and mine, is that the craft you create requires visual-brain interaction of the type we generally call reading, and the most heartbreakingly illiterate of the beasts on the planet are those you most need to reach. They are the tragedy, not you and your wonderful work.

You inspired me to blog and that has saved my life. You linked to all my other discoveries and that has changed my life. You introduced countless beginning blogger/writers to an entirely new way of being in the world and you say so often what we are all thinking.

Perhaps the one thing I could say to you that would lift your spirits the most is that in the most depressingly backwards place on earth, down here in lower Alabama, things are changing. When I pick up the paper to read that the town I loathed for so many years that I would not return to it has started holding meetings with the guru of New Urban movements and participating in the 23rd Coastal Cleanup(http://blog.al.com/live/2010/09/coastal_cleanup_held_saturday.html) or added All Things Considered and Morning Edition to daily radio broadcasts (we had to listen to MPB for so many years before the Bush era horrified even the most staunch conservatives with a taste for classical music)or that even your book could be read here in this last vestige of ignorance left in the US (if you don’t think that’s fair, read the comments on the same al.com site any day of the week) and you might be hopeful that we are listening.

Whether we can save the world is yet to be determined, and someone much younger than I will answer that someday. I only know that I am profoundly grateful to you as one of the gifts that came with the Salon.com package I opened so many years ago it’s hard to realize. I wish we’d all known you sooner. But then you wouldn’t have had a thing to write about.

Love you much. Hope my book gets here soon, because I need to save my students from despair and my friends from doubting that my idealistic dreams can finally be realized.

Susan Hales

Living in my sleep. It’s not bad. But it’s not enough. I owe myself, and the world, more.

I am thinking that you still need to answer for yourself, at a fundamental level … why you owe the world or yourself anything more than what you have already done in life.

As I know your story, you were in other- and self-imposed chains for what … 20+ years ? What’s wrong with doing nothing or just fun-and-easy for a year, or maybe two ?

Maybe you should travel more, and mainly on foot and local travel, to places you would not have seen when traveling to meetings or group think-tank dialogues .. rural Peru, the south of India, Mongolia .. I don’t know.

What I think is a possibility is that you are still feeling “guilty” about those 30+ years in servitude to masters other than your own choosing, which I think is very hard on your self (just as it is hard on others but they may not know that, not having walked through a break and then growth in consciousness).

After all, when you made those choices … CA degree, work for a large corporate accounting / consulting firm, not stopping working until you had enough protection amassed to not worry … here you are still worrying.

You did not have enough context nor experience to understand the miasma into which you entered in your early 20’s … none or very few of us had (ppl like B. Fuller and E. Schumacher, Hawken, etc. excepted perhaps), so why should you spend so much time and energy flagellating yourself for not being able to completely sort out the irrational and large-system obstacles that capitalism and corporatism (as two of the factors) offer us all ?

Can’t you just put out that ongoing fire in your hair for a year or two, and let your past go ?

I feel able to say the above because I have been working through a similar relinquishing for the past 15 years, so I have some sense of how deep the perceptions and feelings go, and just how well much of what doesn’t work for me today was internalized as “the way things are or should be”.

Guilt and anxiety about rejecting that are normal, and don’t disappear easily just because you have the intellectual insight that they are not the formidable opponents one makes them out to be.

Still arguing with reality, Dave? Our feelings stem from thoughts. Negative feelings stem from believing untrue thoughts. While you may be free in one sense, it doesn’t sound like your mind is free yet. Question your thoughts and free your mind. Byron Katie tells us how.

Still loving reality.

It distresses me to see so many comments that project an underlying contempt for process, for change, for transition – call it what you like. Your extraordinary skill in documenting what is happening in your life has helped me a great deal to understand what is happening in mine.

I retired almost a year ago from a high-tech “career” in which jobs/residences spanned 6 months – 2 years, thanks to the capitalist posture that foreign workers are smarter than US-educated ones. (I graduated Dean’s List from Johns Hopkins University, so that tells you something about management-speak rationalization.) I had wound up in upstate New York, and my last winter there I came down with pneumonia twice. So I cashed in all my pathetically-dwindled pension funds and moved South. Along the way I bought sufficient tools/toys to allow me to indulge in high-tech proposal development to support job creation in the South for local tech graduates and my passion for classical music and operatic composition.

After 8 months of humiliation I accepted the reality that no organization, public or private, wants my skills – even if they are freely given. The marketplace has degenerated sufficiently that creativity has become a terrorist activity. “They” are marginally OK with my ability to stuff envelopes and run the copier, but that’s it. I have not been able to access any creative energy at all – the opera is still floating around in my head and my house needs painting.

Some of your correspondents suggest that exhaustion is the root of your transition, but I believe that I am working out mid-stage grief; and I am getting irritated by well-meaning but ignorant observers trying to talk me out of how long it is taking. The identification of what I am grieving (a life wasted in doing the “right” thing?) is no longer important. The shifting timeframe has begun to intrigue me, and the providential interruptions of the cycle encourage me to believe that there is an end/new beginning and endurance is the key.

A couple of weeks ago I attended a spiritual retreat, just for something to do that would shake up my routines. Well, it surely did. The guide was Matthew Linn, a Jesuit priest who uses a method that combines neurosciences advances in polypeptide research (e.g., Candace Pert, Ph.D.) with the spiritual exercises of St, Ignatius (without the dense Catholic long-windedness).

The process/transition has accelerated. Now I have nightly vivid dreams of my past and a host of transitory physical ailments that make no sense. The mind-body communication is remarkable – quite an adventure.

I wouldn’t dream of “selling” you a similar retreat; the process is also very painful. But something unexpected will come along in your life, and the gate will creak open. I hope that you will continue to document the transition.

Dave, you are just one person – we all are just one person. It would do for everyone feeling like they have no power to remember that: and then remember that the vast majority of “just one” people are less than one in the blind eyes of the system. It’s an imposition, but those of us who are able to be “just” one have a duty to do what we can, when we can, as long as we are able.

We also need a rest sometimes.

Your friend

Keith

http://www.deepsurvival.com/ …

http://www.amazon.com/Deep-Survival-Who-Lives-Dies/dp/0393326152

http://www.questionsforliving.com/revisions/projects/scenario-training/deep_survival_gonzales.php

“What are the most useful questions that an individual should ask in a survival situation?

Mr. Gonzales:

1) What is your motivation for getting back to life? People who are socially connected have a better chance of survival. People tend to do it for something other than themselves.

2) Why bother surviving? What is the point?

It is necessary to cultivate a deep sense of purpose and personal connection.

3) Where is the beauty now?

There is always beauty and it is important to be open to it. Being aware of the beauty helps develop the sense of purpose and makes one aware of their surroundings. It is possible that being aware of the beauty also helps the brain relax and respond better to the changing circumstances.”

Kevin, Ed, Susan, Jon, Steve, Margherite and Keith: Thank you. Your reassurances, clarifications, comments, personal stories and exhortations are noted and appreciated.

A few months ago I wrote about three First Principles for coping with the modern world and making the world a better place:

Be generous. Value your time. Live naturally.

Now I am coming to believe that

Self-accept. Practice being present. Let go of stories.

might be the next three First Principles, quite a bit harder than the first three to do.

These six principles are not a prescription for what to do or how to do it — we don’t need more ‘solutions’, since what we face today are not problems, but predicaments. Instead, they are aspects of how one can present/represent, self-manage, exemplify, “compose” [=”put together”] and express oneself to the world competently, usefully, joyfully and responsibly to the world. How to “be the change”, not by changing oneself, but by being what one has always, under the gunk of modern civilization, been.

Thank you for sharing your struggles with the world. As others have said, lots of your thoughts resonate with what I’m trying to figure out about myself.

Something struck me about your description of your perfect dream life: It sounds almost exactly like Tolkien described how elves life in his Lord of the Rings. And as with them, there is a lot of deep sadness shining through your writing.

(First off, I’m not liking your support for extremism. The hostage crisis at the Discovery channel should show how counter-productive such extremism is, let alone the unabomber before.)

—————-

I write much the same “woe is me” confessionals on my blog, and to whatever extent I get something out of this blog, it’s by holding up a mirror to my own eerily similar mental ruts.

What I see in posts like these are lots of excuses. Excuses for why you can talk the talk but not walk it. To that extent, blogs like this become a crutch where we can rationalize inaction and wallow in martyrdom. But as you’re discovering, even that doesn’t bring inner-peace. So why keep it up?

The fundamental question needs to be asked:

“What do you want?”

If you can’t get it, then what? I’m telling you now that even if all 6.9 billion of us went permaculture granola, you aren’t going to earn a future strolling around in pristine old-growth forests. Even if by some miracle you did, you’d be cognizant of how damn lucky you are, that billions of other humans (outside of whatever magically protected enclave you’d find yourself in) are going to wind up on the losing end of the game of carrying-capacity musical chairs.

So you’ve set the bar too high.

And I wonder how much of that might be intentional? By setting your life up as a simple all-or-nothing binary state of ‘success’ and ‘failure’, you can define success so narrowly that you don’t have to worry about the guilt of failing, and hence not need to try so hard in the first place.

That’s not to say all you need to do is work hard to achieve fulfillment. Life carries with it no guarantees, but if you rule out success at the outset, then you’ve sabotaged whatever small chances you do have!

If you just want to make the world a ‘better’ place without it having to end up a utopia, then I suggest you consider moving out of your comfort zone because the world changes will eventually force the issue sooner or later anyway. Reskill. Learn permaculture and homesteading and all those primitive skills that your beloved hunter-gatherers would need.

I never would have foreseen that I’d be building a freaking geodesic greenhouse in my backyard, but there I am, doing it! Stop seeing your identity in such rigid terms. Your identity was cast during an era of the world that you already despise anyway, so why should you be beholden to it? Adapt or die. But we’re running out of time for any of us to casually muse on doom in the blogosphere.

I can “feel your pain” (as Bill Clinton says) but that by itself is not the answer.

weak personality shifts responsibility away and in the end you are blaming others for not being creative, for wasted time, stress, etc.

you and only you can do pretty much everything.

you do not have to save the world and fight to help other people.

make yourself happy [or at least be in peace with yourself, do not bring others to help you], that will change the world.

finding external explanations – path to loose.

The solution is to gradually become free of societal rewards and learn how to substitute for them rewards that are under one’s own powers. This is not to say that we should abandon every goal endorsed by society; rather, it means that, in addition to or instead of the goals others use to bribe us with, we develop a set of our own.