A quick re-cap of the hypothesis I laid out in parts one and two of Who ‘We’ Are:

- The cells and organs of our bodies evolved our brains as a feature-detection, protection and mobility management device for their purposes. Our cells collectively evolved organs and organisms by trying trillions of trillions of random variations, rolls of the genetic dice over four billion years. The evolutions that best adapted to and fit into the ever-changing global environment survived. It can be shown statistically (as Stephen J Gould did in Full House) that such evolutions will tend to produce greater diversity and complexity of life forms, and the human species is a reasonably but not exceptionally complex adaptation compared to the rest of life on Earth.

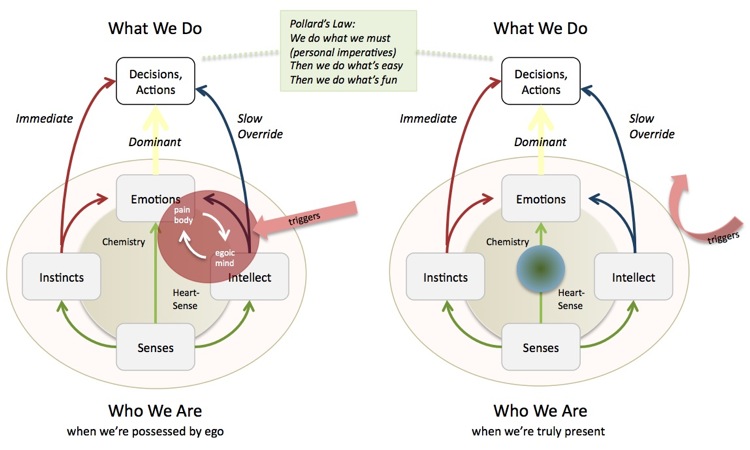

- The ‘existence’ of our minds and identities as ‘individuals’ is therefore self-delusion, self-deception, as Stewart and Cohen explain in Figments of Reality and as John Gray reiterates in Straw Dogs. Our minds are nothing more than processes carried out for the benefit of our cells and organs — they are their information processing system, not ‘ours’. The four aspects of our ‘selves’: intellectual, emotional, sensory and intuitive, are simply the four sets of chemical processes that our cells and organs use, and weigh and balance, in making decisions in their collective best interest, as shown in the upper right chart above. To use Stewart and Cohen’s term, we are a complicity, a complex collaborative ‘folding together’ of the collective interests of our component parts. Each individual creature is plural, not singular. This is true for all complex creatures, not just our species.

- Like most species, we are social creatures. Such creatures evolve codes of behaviour that enable them, as part of the larger organism of all-life-on-Earth, to collaborate, share and keep their numbers in balance with the local ecosystem — these are all evolutionary selected behaviours, since they enable us to adapt and fit well into these ecosystems. These codes of behaviour are called cultures. Cultures are learned rather than genetically innate codes, so they can evolve much faster than our bodies can.

- In times of stress, due to overcrowding, natural disasters, climate change or the exhaustion of local resources, cultures can intervene to act in adaptive ways that would be unneeded in normal times. These ways can include war and other aggressive and violent behaviour (as scientists have observed in mouse populations under stress). They can also include migration and adoption of new diets, new tools and new ways of living that are better suited in evolutionary terms to the changed environment. At some point, for reasons we don’t know, some of our species chose to leave the trees of the tropical rainforest where we lived a leisurely life as vegetarian gatherers for a million years, and struggle to survive in other environments. We evolved weapons to kill other animals , enabling us to live as carnivores, and discovered (by studying plant growth in floodplains and fire-burned areas) what Richard Manning in Against the Grain calls ‘catastrophic’ agriculture (as opposed to sustainable permaculture), enabling us to live where there was insufficient food growing naturally. These new tools, however, required settlement and a very different kind of culture — civilization culture — to sustain.

- Civilization culture requires sacrificing a great many freedoms for the survival of the collective membership, and requires vastly more work, personal sacrifice, hardship, suffering, and vulnerability to catastrophe than other cultures. To keep people from obeying their cells’ and organs’ natural tendencies by just walking away from this culture, it is of necessity inherently coercive, using hierarchy, violence, threat of imprisonment, propaganda and other means to ensure ‘law and order’ — obedience and conformity of the group, without which the new civilized settlements would naturally disintegrate. Two key adaptations to enable this were the evolution of abstract language, suitable for the giving of instructions down the hierarchy and the reporting of information back up, and the concept of clock time. None of this is ‘evil’ — its is all just necessary evolutionary adaptation to a changing environment.

- Whereas our cells and organs had nearly full control of our (their) minds before civilization culture evolved, the new culture was able, through language and coercion, to influence and seize control of a significant part of our minds. There has been a continuing and escalating war for control of our minds ever since. Our culture persuades us that we have ‘free will’ to ignore what our cells and organs impel us to do and instead do what it (our culture) wants us to do — that we have an ego, an identity, and a responsibility to conduct ourselves according to the rules of civilized society, or we must face the social consequences. As Eckhart Tolle explains in his books, the consequence of this great deception is a vicious cycle of egoic mind (fictional stories that our culture has told us are true and ‘factual’) and pain-body (the negative emotions such as anger, fear, guilt, shame and grief that these stories invoke in us). As shown in the illustration above left, the egoic mind and pain-body can be easily triggered by our culture to control or debilitate us, and the resultant psychological illness (which often also manifests as physical illness in the form of chronic stress-related diseases) cripples our ability to be present and at peace in the world. Again, this triggering is not malicious (except when instigated by psychopaths). Our reaction to it is mostly autonomic and beyond our control: We cannot be other than who ‘we’ are.

As I concluded in part two, now that our civilization culture has (as an unintended consequence of its evolution) desolated the Earth, and has begun to collapse, we are left to wonder what will be left of ‘us’, and some of us who believe that culture cannot be ‘saved’ have started to try to liberate ourselves from civilization culture, and our dependence on it, now. I wrote:

This does not mean moving to neo-survival mode, but rather moving away from civilization culture’s broken, desperate, coercive survival mode. Moving from a society whose worldview is one of scarcity, competition, obedience and sacrifice, to one whose worldview is one of abundance, cooperation, independence and generosity. Moving forward to a natural society. One that trusts the wisdom of each individual’s cells, organs, instincts, senses, emotions, intellect, biophilia, to know just what to do, and to act on that holistic wisdom. One that through its connection to all-life-on-Earth intuitively and collectively and wordlessly manages its numbers and behaviour (as most complex natural species do) to contribute to, not destroy, the complexity and diversity of life on our planet. In our cells, in our organs, in our DNA, this is who we are, and who we always have been, except for a few desperate millennia, when we forgot.

In my postscript I mentioned that we can use music and other sensuous stimuli, and love, and perhaps ‘mind-full’ activities such as meditation, gardening etc., to at least temporarily cut through the egoic mind and pain-body that has made us all mentally ill and begin again to function as natural creatures, aware and relaxed, present and at peace, as in the diagram in the upper right. There are many other things we can do as well to liberate ourselves from our crumbling civilization culture:

- Relearn the skills and capacities of community self-sufficiency that will allow us to become less dependent on our fragile, globalized, reeling civilization culture.

- Reconnect with and trust the wisdom of our senses, our instincts, our emotions, our bodies and all-life-on-Earth through personal practices (which will require patience — the disconnections that civilization culture has wreaked on our minds are the result of a lifelong war of propaganda and incapacitation on us and our communities, ostensibly ‘for our own good’).

- Think critically — challenge everything we’re told, turn off the obfuscating media, and recreate local ‘salons’ where people can talk about things that are important again (as opposed to things that are merely urgent, and things that are entertaining and hence distracting) in ways that are re-empowering and community-building

A new thought: The two diagrams above both imply that it is our ‘beliefs’ (what we know or think we know) that drive our behaviours, our actions. I’m now in the process of reading David McRaney’s You Are Not So Smart, and in this book he argues that it is the opposite: our actions and behaviours inform and determine our beliefs.

What actually happens in our minds, he writes, is that we act first, and then rationalize and self-justify our actions. Our minds don’t ‘decide’ at all. The decision is made for us by our cells and organs, or by our culture, whichever has the upper hand in the moment (or perhaps a mix of both, which can make our behaviour confusing and inconsistent). Whichever has the upper hand is determined by how susceptible we are to (or skeptical we are of) the messages of our culture, and how we understand those messages; by how powerful and clear and trusted the messages our senses and intuition send us are; by how much information we have and how unambiguous that information is; and most of all by which has most influence over the chemicals that are rushing through our bodies in the moment: our cells and organs or the pain-body our culture is triggering in us. ‘We’ have nothing to do with it.

When there is a cognitive dissonance between our behaviour and our beliefs, we attempt to resolve it by adjusting our beliefs, rather than changing our behaviour. Why should this be so? My hypothesis is:

- Our beliefs, conceptions and worldview are simplified models of reality created in our minds. Before the influence of our culture became so pervasive, these were, like upper legislatures were once supposed to be, places where actions could be second-thought, analyzed, assessed for effectiveness. These assessments, ‘stories’ about what happened and why, may be used to prompt overriding or mitigating actions, and to ‘re-mind’ the emotions if that situation occurs again. An excellent adaptation of the brain’s information processing capacities by our cells and organs.

- But now that most of these ‘stories’ are propagated by our culture, not formed from personal body-assessed experience, the egoic mind and pain-body interfere with our natural decision-making process. Our culture can play with us as if we are puppets by triggering the appropriate negative emotions, invoking the appropriate fictional ‘stories’ of what happened and why, and making us behave the way it wants us to. Now we have to reconcile what we have done with what we believe, by altering inconsistencies between our actions and beliefs the only way we can — by changing our beliefs to justify and rationalize our behaviour — so we can ‘live with’ ourselves. Our culture is, of course, delighted with this reinforcement of its message.

So our beliefs and worldview are not a moral or behavioural compass that is used in guiding how we live our lives. On the contrary, our beliefs and worldview are our rationalizations for what we have done and are doing, and why.

This does not require that the arrows in the models depicted above need to be reversed. Who ‘we’ are is not our beliefs or our worldviews. What the models need, to reflect that our behaviours and actions drive our beliefs, is an additional ‘feedback’ arrow from the Decisions and Actions box back to the Intellect box. On the right side, this might be called ‘learning and modelling of reality’. On the left side, it is these things too, but also ‘rationalization and justification’, because when we’re afflicted with egoic mind and pain-body, without rationalization and justification for actions that otherwise make no sense, we cannot live with our ‘selves’.

Why is it important (at least to me) to have some kind of explanation for who ‘we’ are, some model that makes sense of how and what we think and feel and believe and do? I believe self-knowledge is one of the most important and difficult to achieve of the essential capacities we need to acquire to be ready to cope with the challenges we face in the years ahead. I believe our civilization’s collapse has already begun, that it is irreversible and will bring with it an enormous amount of suffering (not that our world isn’t already filled with suffering). How can we hope to be able to deal with the cascading crises of economic, energy and ecological crises likely to roll over us in the Long Emergency decades of this century, if we don’t know ourselves, and our motivations, and if we’re not sufficiently self-aware and present and at peace with ourselves to competently self-manage, deal with crisis, and create healthy, sustainable communities in the aftermath of civilization’s collapse?

I hope this is a useful, or at least interesting, model of ‘self’ for you to think about as you work on building your personal capacities for resilience and your own projects to find better ways to live, now and for the generations to come.