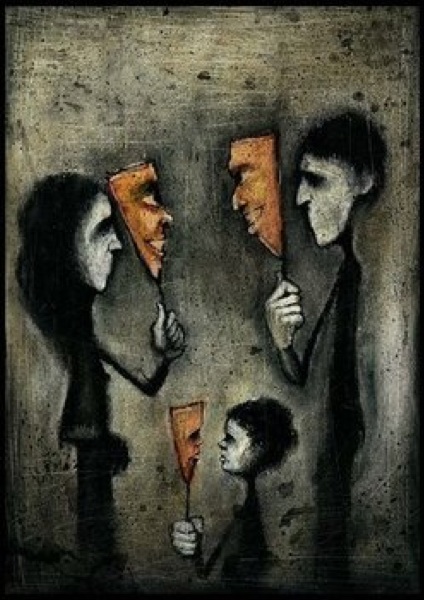

image from the collection of Nick Smith, “possibly by John Wareham”

All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players; they have their exits and their entrances; and one man in his time plays many parts. — William Shakespeare, As You Like It

The etymology of words that relate to personhood and identity is fascinating: Person, personality and persona, from the Latin meaning a mask; role, from the Old French meaning the roll of paper on which an actor’s lines are written; and, strangely, identity and character, both from the Latin, meaning, respectively, sameness and uniqueness.

The word self was originally not a noun, not a word that described anything substantial, but rather a reflexive modifier, se, a pointing back to the subject, used to ‘complete’ a description of an action that has no object; so in French elle se souvient = she (herself) remembers, which doesn’t refer at all to any such ‘thing’ as a ‘self’ but rather refers to who is doing the remembering.

I’m not suggesting that early Indo-European cultures had no sense of themselves. Rather, this absence of concrete terms that describe the self, the person, would, I think, most likely mean that the language of the time had no need for a term apart from the name or pronoun that describes a person. They were themselves, so why would they need a term for ‘themselves’, or for ‘persons’ or ‘identities’? It was only in play, in acting as someone other than themselves, that they would have to evolve a term for the role they were not playing, the mask beneath the mask they were wearing, for a while, separate from ‘themselves’.

We can of course not know whether prehistoric or preliterate cultures “played many parts”, and if so whether they were aware they were doing so. It’s likely they were as aware, and unaware, of the many roles they took on, their personas in different contexts of action and relationship, as we are today. Which is to say, only vaguely aware. We take on different personas, “play different parts”, in our roles as parents, lovers, workers, friends and colleagues, and we slide from one to another as automatically as a a voice-over actor playing multiple parts.

We “act (and think) differently” when we speak other languages, and when we’re intoxicated, not “ourselves”. In different relationships we may take on and take off whole sets of beliefs, worldviews, mindsets, and behaviours, based on completely different “stories of self”, in order to achieve comprehension, appreciation, and useful communication with others. And some of these different belief-laden personas can be completely incongruous with others, which can both alleviate and create enormous internal cognitive dissonance.

So for example, I had a long talk the other day (details to come soon) about collapse, and how we might best deal with it, based on my recent post Being Adaptable: A Reminder List. Just before the call, I had sent an email to someone else on the matter of free will, and I was aware that, to handle this new conversation competently, I had to “flick a switch” from the third to the second of three personas, each of which (these days) gets a regular turn at bat. I suppose I could label them as follows:

- Compassionate Humanist Dave: Open to the possibility that there are things that can and should/must be done to mitigate and forestall the effects of the profound economic and ecological crises facing us and cascading over us, even if they don’t achieve clear or lasting results. “We can’t just do nothing.”

- Collapsnik Dave: Resigned to the impossibility of preventing the slow unraveling and final collapse of our global industrial civilization in this century, ushering in (probably) several millennia of instability, terrifying and exhilarating precarity, great migration, radical relearning, and plummeting human numbers (mostly due to our almost completely ceasing to procreate during the chaos, rather than due to homicide, starvation or disease), before (maybe, if we’re lucky) many thousands of new, local, astonishingly diverse, joyful and sustainable human cultures emerge in an unrecognizable post-collapse world. “There is nothing we can do.”

- Radical Non-Duality Dave: Convinced that there is no real ‘you’ or ‘me’, nothing real or separate, no space or time, only the wondrous appearance of everything out of nothing, and no need for there to be anyone or anything separate, no purpose or meaning, nothing really happening, and that this illusion of separate individuals with free will and choice and control over the bodies they presume to inhabit was an unfortunate evolutionary accident, but one that the illusory self, hopelessly, cannot escape — there is no path. “There is no ‘we’ to do anything.”

I think this second persona played its part relatively well today, with no inadvertent slips into switch positions 1 or 3, with all the confusion, annoyance and cognitive dissonance that could have produced.

What makes this subconscious role-playing even more complicated is that all three of these ‘voices of me’ have beliefs at the (mostly radical) end of different spectra: The compassionate humanist thinks anything short of direct action is a waste of time and energy, to the chagrin of many other humanists. I am at odds with many under the collapsnik umbrella, who I see as lacking a historically-based, nuanced and equanimous perspective about what collapse will bring and how we might approach it. And my radical non-dualist beliefs understandably infuriate those who have invested years on “spiritual paths”.

And at another level, these three personas are only a subset of the complex set of roles I play. They are, all three, amalgams of who I think other people want me to be (mainly, useful to them in some way — clarifying or creatively challenging or reassuring or attentive or appreciative), and who I imagine (or would like to imagine) myself to be (usually some combination of sensitive, sympathetic, and brilliantly and engagingly ahead of my time). And humble!

Each of these personas has its own ‘story of me’, a general script that smooths over the improvisational gaps between the lines that ‘I’ have been conditioned to deliver (or at least that’s how persona 3 sees it). Each defends a position, completely incompatible with the view of the other two personas, and each tries its best to help others with similar worldviews. None of the personas is interested, any more, in trying to change anyone’s mind.

Invite me to a meeting of young female entrepreneurs and persona 1 will show up, eager and supportive and full of experienced and heartfelt advice. On the way home I will text a fellow collapsnik about XR in persona 2, oblivious to the fact that what I told the young women is utterly incongruous with what I have just texted. And when I get home I will write a blog post in persona 3 about the illusion of separation, that belies what I just said at the meeting and what I just texted.

Perhaps my personas are a bit more schizophrenic than most people’s, but my sense is we all do this. In our zeal to assume each role, we ignore its cognitive dissonance with the last one we played, and in the process the alleged real ‘us’ gets more and more buried under the conditioned (and self-conditioned) gunk that we must, to be true to the role, hide behind.

Occasionally I think I see, underlying all of these personas, another ‘story of me’ that seems, somehow, more raw and honest (or maybe, to be ‘really’ honest, more self-indulgent, disingenuous and falsely self-deprecating) — the ‘me’ that is lost, scared and bewildered, and trying to figure out whether it’s alone in that, or if all the people it meets, who once seemed to it so certain and ‘together’ and competent and self-directed, are just lying to themselves, and the world. Just like ‘me’.

And then there’s this (hyper-)reactive ‘me’ who I’m quite ashamed of, who comes off quite badly in all three personas but still rears his angry, fearful, unhappy head way too often. And there’s the always-aching-to-fall-in-love ‘me’, who keeps forgetting both how wonderful that feels and how utterly self-invented and unsustainable that chemical state, and its absurd beliefs, are. But don’t remind me that when I’m in love, because that me won’t hear you.

None of these personas is real. They are all just parts, masks. In a world where there is [flicking the switch to position 3 again] nothing separate, no thing apart, we are all just acting a part — or perhaps it would be more accurate to say we are acting apart. Pretending. (Pretend and temporal are from the same root word, meaning — of course — something that doesn’t last. Only a lifetime! And oh! what might be beneath that mask, what is being ‘mask-ed’? no!…)

I remember as a child watching adults and asking myself if they were all just acting, and if so for whose benefit, because somehow I knew that everyone was just as lost, scared and bewildered as I was. But hear or see something (apparently) often enough, and you’ll come to believe it’s real. The war between your remembrance and intuitive ‘knowing’ of there being nothing separate, just perfectly everything, on one side, and your self and every other self working furiously to convince you otherwise, on the other, is an endless war of attrition. ‘You’ cannot win.

I cannot recommend strongly enough the book Constructing The Self, Constructing America by Philip Cushman. Published in 1995 by Addison Wesley. In particular, chapter 2 “Selves, Illnesses, Healers, Technologies” is relevant to your discussion in this post.

See this short animation:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=141&v=OBJXgdOpskU

If one begins with the notion that we are our interactions (as opposed to some carved in stone definition), then it is clear that we must have a library of interaction styles which can be adapted to a particular situation. Because we are reacting in real time and cannot be entirely flexible. Consequently, the sum total of Dave is actually the sum total of how he interacts in different situations. Now one can use that fact to either argue that ‘Dave doesn’t exist’ or else assume that ‘Dave is the integral of all his interactions’. The latter is related to the question of whether a circle exists. If we accept integral calculus, the circle exists. If we keep looking for more infinitesimals, then I suppose one could argue that the circle really doesn’t exist. But that is pointless.

If one accepts the ‘integral of interactions’ definition, then, as Dave learns more subtle ways of interacting, the integral changes and Dave changes. Again, one could argue that ‘the real Dave doesn’t exist’…but again that is pointless.

Don Stewart

Like you, I too notice inconsistent modes of my thought. When I notice contradictions or tensions among them, I usually figure it’s impossible to reconcile them, and I try to ignore the conflict. Underneath lies the suspicion that life is meaningless–in which case it doesn’t matter–and that “truth” is overvalued.

Is the concept of “authenticity” merely a conceit? A school of thought has argued for years that we might be happier if we came closer to being our “authentic” selves, peeling off a lot of the conditioning of our lives. (You argued in the past for removing “the fictional egoic ‘gunk’ that our culture has, throughout our lives, layered on us, our ‘selves’”.) Perhaps the authentic self is just a mirage that continues to appear in the distance, unapproachable, or something to barely approximate, like virtue–when falling back into the illusion of free will.

A recurring interest in non-duality brought me back here today – I think 3 can be reconciled with the others if you see it as just what’s happening. Relation to others is happening in all these ways.

I don’t think I have such strong personas, with a very fragmented sense of identity – I’ve been wondering if this is a common thing for autistic people or I’m just naturally not very attached to identity and I’ve felt pressured into having one because more people respond to apparent confidence in some area of the world.

Whatever’s happening to me, or just arising is a trouble having the same investment others have in work, or I don’t think I ever have and I just manage to do enough to derive an income. No pride seems to stick to anything I am regarded to have achieved. It may be fine to just notice others value what you do whatever mode you’re in and however it is fed by other’s apparent enthusiasm or commitment.

That’s my occasional ramble on your blog for now…

You have a wonderful way with words. I can imagine a future where specificity becomes more and more important in our Western discourse.

I have always liked reading your blog over the years. I remember when you were back on blogspot or blogger, or whatever company it was. I’m glad to see you’re giving a lot of lectures now and writing books.