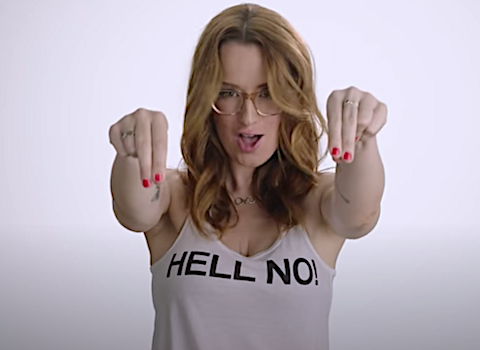

Ingrid Michaelson in her enormously-fun video of the song Hell No! signs the word “no”. If you want to know the meaning of the other useful ASL signs in the images below, you’ll have to watch the video!

In a recent conversation with Tree Bressen, we talked about people we knew who had no idea what they wanted — in a relationship, in a job, in a home, or in their personal lives. But they were quite clear about what they didn’t want. It occurred to me that this probably applies to most people and most of their preferences and choices.

Whenever I have had a particularly momentous decision to make — say, where to live, which house to rent, what car to buy, what investments to make — I usually end up listing the criteria, applying a weight to each criterion, ‘scoring’ each of the alternatives… and then completely ignoring the total scores when it becomes clear to me I’ve already made the decision.

What I really want the score to do is justify that decision — to make it plain, and compelling, why I made that choice. When I do that — when I start rejigging the weights and scores until they match my decision — I realize that I’m mostly raising the weights of criteria that are negatives. I’m stacking the deck against options that, for all their advantages, have some attribute that I know I don’t want.

In other words, the decision process is largely a process of elimination of the various alternatives, starting with the ones that have some feature I know I’m not comfortable with.

While I know I have a propensity to be risk-averse, this seems a most unfortunate basis for making a decision. But think about a lot of the decisions we make: Who to vote for, what to make or order for dinner, which shirt to buy. Mostly, I think, we winnow it down and then make the decision by deletion, based on something we know we don’t want.

Ranked voting choices provide a particular dilemma. You are supposed to list your choices from 1 to n, until you have no further ‘positive’ choices, and leave the space beside the rest of the candidates blank. But how can you resist putting the highest number beside that particularly loathsome candidate, and then working backwards to your favourite?

Our preferences are clearly conditioned — both by our biology (eg early food preferences) and by our culture (eg music we like). And there’s plenty of evidence that ‘we’ don’t actually make any choices at all — our mental gymnastics are all designed to make sense of what we had, due to our conditioning and the circumstances of the moment, already ‘decided’ to do. Radical non-dualists (those who no longer have any sense of self or separation) say that their preferences remain as they always were, based on their conditioning; there is just no longer any attempt to rationalize or make sense of them, or to identify them as ‘theirs’.

Why would we evolve such that our ‘negative’ preferences — what we know we don’t want — are clearer to us, and more important in our conditioned choices, than ‘positive’ preferences?

When it comes to what we eat, most wild creatures learn by watching their mother and smelling their mother’s breath. That conditions them to not eat dangerous or poisonous foods, which is more critical to survival than selecting the most nutritious.

When it comes to choosing a mate, nature leads us to look first at health — strength, fitness, energy, positivity, beauty — and to reject candidates who we instinctively sense to be poor choices for child-raising. There have been studies that show that on average we settle down with someone after 7-10 serious relationships (and a similar number of sexual partners). The unanswerable question is whether holding out longer would lead to a happier long-term relationship, or would simply reduce the number of ‘available’ partners to choose from, leading to a less satisfactory relationship, or none at all.

There is strongly conflicting evidence about whether having had more relationships before settling down improves happiness thereafter, and also about whether second marriages or equivalent settled relationships are any happier than first ones.

My guess would be that in tribal cultures the average number of relationships before entering into a marriage or equivalent relationship is much lower than the 7-10 average in our modern culture. And I also suspect that many or most couples who stay together for years or a lifetime are more likely to do so because it’s not bad than because they’re actually happier. In other words, they stay together because they don’t want to split up rather than because they do want to be together. In fact, if you buy the arguments in the famous Dan Gilbert talk, our happiness (and unhappiness) is, by our very nature, not sustainable anyway, no matter our circumstances.

So perhaps that 7-10 relationship average is just the result of our conditioning, and finally encountering sufficiently few “don’t want that” triggers to prevent our natural evolutionary tendency to mate from having us stay with our latest relationship. “I don’t know for sure if I want this to be my primary, lifelong relationship, but I do know that I don’t not want it to be so. I could hold out for something ‘even’ better, but something instinctive is telling me not to do so. I don’t want to be alone, and the arguments for waiting longer until I find what I absolutely know I want are not compelling.” Very unromantic, but my guess is that many of us (or at least our conditioned bodies and our rationalizing selves) have ‘decided’ in exactly this way.

Of course, that’s not how it feels. When we fall in love, or lust, the chemistry is all about what we want. Nature is so clever that she’ll use our own body chemistry to obscure facets of our love-interest about which, with a clearer head, we would quickly say “Damn, I don’t want that“. But soon enough, the intoxication wears off, and we’re back to being just indifferently unhappy, wanting something new, something else, something that’s missing, and all too aware of what we didn’t realize, in the haze, we didn’t want.

I look at the trajectory of my life, and my sense is that I need and want much less than I did when I was younger, but that my apparent decisions are still based more on aversion (mostly to stress, anxiety, and my many fears) than on attraction. It’s still clearer to me what I don’t want (a sizeable list) than what I want (a very short one). But perhaps that’s just me, and getting old.

When I have spoken to people in my circles about this, it’s been astonishingly easy to reframe much of what they say they think they want (better relationships, adventures, fun, material comforts, freedom, joy, purpose) into terms of what they don’t want (acrimony, loneliness, stress, boredom, obligation, anxiety, responsibility, and the sense of helplessness and hopelessness). Is that just semantics or is there more to it?

I’m not sure how important all this is — probably not enough to warrant declaring it to be one of Pollard’s Laws, but it is interesting.

So — How well do you think you know what you want, versus knowing what you don’t want? What decisions in your life have apparently been driven by the weight of positive criteria, rather than by the avoidance of negative ones? What, more than anything else, do you (positively) want? And is that something more than freedom from what you don’t want?

It doesn’t seem to matter what we want or not want. In the absence of any free will we seem to get what is given to us. I don’t take credit for being born white anymore than Zuckerberg should take for being a billionaire. It’s not determinant on aspiration. I think for those who do try to make choices the negative is easier to define as it is by its nature a limiting, truncating mode of thought. “I don’t want children” is more final than “I think I would like kids.” What you DO want opens up the field of possibilities and hence the chaos of chance. I suppose there are people that are exactly where they planned to be in life but I’ve never met one. I would suspect those people arrived there more through luck than any design. Throughout my life I can see broad trends, situations and people that I avoid or gravitate to but I can’t say any of this was my choosing. More likely it was just preconditioning that influenced my judgements.

After a while the idea of what you want becomes less relevant. Certainly once one starts to operate less from the ego, the idea of desire for things to be a particular way becomes less important. The dance of consciousness only has one quality to it – the wonderfulness of the dance.

It does seem like risk aversion set against ambition. Or the desire for comfort and ease and security against the effort required to create something new.

It’s worth saying that many people don’t have the possibility of choosing what they want and settle for something that is marginally improved.

And regarding relationships it’s quite possible to feel “tricked” into producing some offspring and later on find there wasn’t that much interest in the “relationship” part which is surrounded by a load of myth and stories anyway.

It would be interesting to try framing things by positive criteria only, even if it’s just another way of rationalising an apparent decision. I guess the other outcome would be realising when no real decision was made and not feeling excessively bound to it as something you have to define your existence by.

Neuroscience confirms that to be truly happy, you will always need something more

https://qz.com/684940/neuroscience-confirms-that-to-be-truly-happy-you-will-always-need-something-more/

The title & notion is contradictory, but still worth the read.

Thanks for the comments. The guy referred to in the QZ article, Jaak Panksepp, was an interesting guy. But since his natural antidepressant failed Phase III trials and was abandoned in 2019, it suggests that neuroscience still has a long way to go to achieve what Jaak dreamt of. His idea of the 7 “affective” feelings and corresponding instinctive emotional behaviours is quite intriguing: Anger -> Rage, Anxiety -> Fear, Sadness -> Grief/Panic, Pleasure-Craving -> Lust/Love, Joy -> Playfulness, Affection -> Care/Protection, and Enthusiasm/Curiosity -> Seeking/Exploration. He claimed they’re common in all mammals, and perhaps all animals.

While it seems pretty clear that the instinctive emotional behaviours are universal, what I’d love to know is whether the affective feelings underlying them manifest differently in non-human animals. If they do, and I suspect that, because of the uniquely human concepts of separation and self-hood, they do, that might explain why Jaak’s chemical cure for depression, which seemed to work so well on other animals, ultimately didn’t work on humans. It could be that the unique mental illness caused by our sense of separation and self-hood might nullify the chemicals’ effects. While both a mouse and a human may show similar grief and/or panic behaviours (eg when their child is hurt), the underlying sadness that provokes it might be very different in a species like mice that do not attribute a ‘meaning’ or ’cause’ or ‘actor’ to what happened (and need not do so to respond appropriately and instinctively), versus a species like humans that can get caught up in the continuously self-reinforcing cycle of (to use Eckhart Tolle’s terms) emotional pain-body responses and egoic thinking (blame, causality, meaning) and hence often respond in an exaggerated and inappropriate way rather than just instinctively, so that chemicals that work for the mouse are inadequate to heal the human.

“Radical non-dualists (those who no longer have any sense of self or separation)” hmmm, you really think Jim Newman, with that seeming endless wit, or Nancy Neithercutt, with the seeming endless selfie videos, that they have no sense of self??

Yes, David, that’s exactly what I think. That’s not to say there aren’t preferences there, or personality traits. Those are present in any character, the result of innate and cultural conditioning. But to take those as evidence that there is an “individual” there is a misunderstanding.